Desmond Lee

Tuttle, Robert J.

Robert J. Tuttle (1935- ) is an American nuclear engineer and the author of The Fourth Source: Effects of  Natural Nuclear Reactors[1148], which is a ground-breaking review of “how the effects of nature’s own nuclear reactors have shaped the Earth, the Solar System, the Universe, and the history of life as we know it.”

Natural Nuclear Reactors[1148], which is a ground-breaking review of “how the effects of nature’s own nuclear reactors have shaped the Earth, the Solar System, the Universe, and the history of life as we know it.”

This large volume (580 pages) challenges many accepted theories, such as glaciation, evolution, and mass extinctions and offers new ideas that will undoubtedly raise eyebrows(a).*The first 25 pages can be downloaded as a free pdf file.*

Surprisingly, Tuttle also tackles the question of Atlantis (p.301) suggesting the possibility that when sea levels were lower, the Balearic Islands in the Western Mediterranean were more extensive and possibly the home of Atlantis. He takes issue with Bury and Lee who refer to the ‘Atlantic Ocean’, which he claims should read as the ‘Sea of Atlantis’ and locates the ‘Pillars of Herakles’ somewhere between Tunisia, Sicily and the toe of Italy.

*(a) https://www.universal-publishers.com/book.php?method=ISBN&book=1612330770*

Wells, Joseph Warren *

Joseph Warren Wells is an American computer software expert specialising in Internet  security. He has also been engaged in over 30 years of Greek and 20 years of Coptic studies. He is probably best known for his Sahidica trilogy which deals with the New Testament in the Sahidic dialect of pre-Islamic Coptic(a).

security. He has also been engaged in over 30 years of Greek and 20 years of Coptic studies. He is probably best known for his Sahidica trilogy which deals with the New Testament in the Sahidic dialect of pre-Islamic Coptic(a).

Wells has also contributed to Atlantology with a number of useful works that includes a concordance of the Atlantis texts of both the Bury and Jowett translations, which can be downloaded as an e-book(b) for less than €3. A free download of just the Jowett translation plus a concordance is also available(c).

Wells has also written about sexual elements contained in the Atlantis narrative.

2011 saw Wells add to his valuable contribution to Atlantis research with the publication of Atlantis in Context[787]and a slightly condensed edition of it, The Book on Atlantis[783]. In them, he offers a new translation of the Atlantis passages in Plato’s Critias and Timaeus and more importantly engages in a forensic examination of Timaeus 24e-25d, which contains some of the most debated elements in the narrative. However, I was disappointed that he did not expand on Plato’s use of words for various bodies of water and in particular the reference to the ‘ocean’ being navigable in those days, inferring that it was no longer so, which begs the question of how this could possibly refer to what we know as the Atlantic Ocean. That aside, Atlantis in Context is an important addition to Atlantis studies.

A 2008 version of his valuable Atlantis work entitled Plato’s Atlantis is still available online(f). This edition also includes a useful concordance to Jowett’s translation of the Atlantis narrative.

On an older website of his, Wells offered parallel versions of a section of Timaeus by Jowett, Bury, Lee and his own(d).

Wells has also brought together the Greek text as well as seven translations of the most quoted Atlantis passages in Timaeus from 24d to 25d, now available on the AtlantisOnline website(e).

Despite all that, Wells does not appear to support the reality of Atlantis!

(a) https://www.logos.com/product/5965/sahidic-coptic-collection

(b) https://www.lulu.com/product/file-download/a-concordance-for-platos-atlantis-burys-and-jowetts-translations/779346?productTrackingContext=product_view/more_by_author/right/2 (Link broken) *

(d) https://web.archive.org/web/20070217220641/https://www.greekatlantis.com:80/timaeus4.html

(e) https://atlantisonline.smfforfree2.com/index.php/topic,3584.0.html

Sable vestments

‘Sable vestments’ is Robert Bury’s and W.R.M. Lamb‘s translation of the Greek kuanon stolen in Critias 120b which describes the ceremonies of the Atlantean rulers when they meet. At first sight it appeared to me that this might be a reference to a need for fur robes implying a cold northern climate, compatible with the habitat of the sable.

Atlantean rulers when they meet. At first sight it appeared to me that this might be a reference to a need for fur robes implying a cold northern climate, compatible with the habitat of the sable.

Anton Mifsud advised me that the Greek text more correctly translates as ‘dark-blue garments’ confirming both Jowett and Thomas Taylor, who translate kuanos as ‘azure’. Other translations on offer are ‘dark blue‘ (Lee), ‘steel blue‘ (Wells) and ‘purple‘ (David Horan). It is more commonly referred to nowadays as ‘Tyrian purple’.

>Into this mix we must throw the fact that the ancient Greeks had no word for ‘blue’. They were not alone as “There isn’t a single term for “blue” in Russian. The two phrases “galoboy” and “sini,” which are typically translated as “light blue” and “dark blue,” are used instead. Nevertheless, for Russians, these words refer to two entirely distinct colors rather than two variations of the same color.”(a)<

If this reference to azure robes was actually recounted to Solon, and not just a Platonic embellishment, it places Atlantis in the 2nd millennium BC, which was when the earliest reference to the production of ‘Tyrian dye’ by the Phoenicians is recorded (See: Murex). The use of purple and indigo clothing was a fashion statement by the political and religious elite that lasted for at least three millennia, which can be seen on the coronation portrait of Britain’s King George VI.

English Translations (L)

English Translations of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias have been freely available since 1793 when Thomas Taylor produced his translation.

In 1804 Taylor published the first English translation of the entire Platonic corpus. In 1871, Benjamin Jowett produced the most commonly quoted version of the Atlantis Dialogues, principally because his work is now out of copyright. Henry Davis produced a translation of Critias in the 19th century and John Alexander Stewart also offered a translation of Critias early in the 20th century.

1925 saw W.R.M. Lamb publish a translation of some of Plato’s works and today his rendering of both Timaeus and Critias is used by the Perseus Digital Library(a). In 1929, Lewis Spence included a composite version of the Atlantis texts in The History of Atlantis, using the English translations of Jowett and Archer-Hind for Timaeus and the French translations of Jolibois and Negris for Critias. Rev. R. G. Bury gave us what was arguably the best translation of the Dialogues (Loeb Classical Library, 1929) and is included at the beginning of this book. Francis M. Cornford (1874-1943) published his Timaeus (Bobbs-Merrill, 1937)

Sir Desmond Lee produced a new English translation in 1972 (Penguin)

Professor Diskin Clay delivered an acclaimed translation of Critias (Hackett Publishing, 1997). Professor Donald J. Zeyl offered a new translation of Timaeus (Hackett Publishing, 2000). Dr. Peter Kalkavage published a highly regarded translation of Timaeus (Focus Philosophical Library, 2001).

In 2008, Robin Waterfield offered a new translation of Critias and Timaeus[0922] as well as a revision of Desmond Lee’s translation of them by Thomas Kjeller Johansen.

Lee, Sir Henry Desmond Prichard

Sir Henry Desmond Prichard Lee (1908-1993) was a translator of Plato’s two ‘Atlantis’ dialogues[435]. He taught for many years at Cambridge. Desmond, who clearly did not believe in Atlantis, described Plato’s story as the earliest work of science fiction. He had great difficulty with Orichalcum, which he considered to be a completely imaginary metal and was of the opinion that Plato erroneously added a zero to the original dates given to Solon.

In May 2014, Thorwald C. Franke published his investigation into the fact that an appendix to Lee’s 1971 translation of Timaeus and Critias, concerning Atlantis, was removed from the 2008 edition. His examination of the excised text led him to conclude that Lee had unexpectedly argued for the reality of Atlantis(a).

>However, I think that Franke may have overstated his conclusion according to comments on the Atlantisforschung website, where it is thought that Lee did not go further than admitting “that the Atlantis report could contain a hard historical core.”(b)<

(a) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-desmond-lee.htm

(b) Desmond Lee – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog) *

Johansen, Thomas Kjeller *

Thomas Kjeller Johansen is a reader in Ancient Philosophy at Brasenose  College, Oxford. He has written an academic paper(a) on the degree of truth (or lies) to be found within Timaeus and Critias. I don’t think it is unfair to consider his work as sceptical, even though he acknowledges the possibility of some historical foundation to be found within the text. In 2008 he published a revision of Desmond Lee’s translation of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias.

College, Oxford. He has written an academic paper(a) on the degree of truth (or lies) to be found within Timaeus and Critias. I don’t think it is unfair to consider his work as sceptical, even though he acknowledges the possibility of some historical foundation to be found within the text. In 2008 he published a revision of Desmond Lee’s translation of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias.

Amasis

Amasis II, was the Greek name of Ahmose who reigned from 570-526 BC. Amasis is given by Plato as the  name of the Egyptian pharaoh at the time of Solon’s visit to Sais. However, Phyllis Young Forsyth[266.38] protests that Plato did not claim that Amasis was on the throne at the time of Solon’s visit, but merely identified Sais as the home of Amasis. The English translations of Tim.21e by Bury, Jowett and Lee are compatible with this, as is the German translation of Plato’s text by Franz Susemihl(a). John Michael Greer[0345], among others, supports this view.

name of the Egyptian pharaoh at the time of Solon’s visit to Sais. However, Phyllis Young Forsyth[266.38] protests that Plato did not claim that Amasis was on the throne at the time of Solon’s visit, but merely identified Sais as the home of Amasis. The English translations of Tim.21e by Bury, Jowett and Lee are compatible with this, as is the German translation of Plato’s text by Franz Susemihl(a). John Michael Greer[0345], among others, supports this view.

Firm historical information for this period is often scanty and sometimes contradictory. However, it is thought that Solon left Athens for a number of years and some of that period may have overlapped with part of Amasis’ reign. Herodotus is our principal source of information regarding Amasis and he clearly mentions (Bk.1.30) that Solon was at the court of Amasis. Zhirov quotes the views of V.S. Struve, who believed that Herodotus’ 3rd century BC dates were out by 25 years.

Ivan Linforth strongly disputes[041.300] the idea of Solon meeting Amasis as “chronologically quite improbable”. He claims that Solon (c.630-560 BC) had returned to Athens before the reign of Amasis. John Michael Greer[0345.15], not very convincingly, attempts to counter this idea with the suggestion that at the time of Solon’s visit, Amasis had not yet ascended the throne.

>A more recent refutation of the claim that Plato’s reference to Amasis is an anachronism is offered Diego Ratti(b).<

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20180901011839/https://atlantis-schoppe.de/susemihl.pdf

(b) Solon and anachronism issue (archive.org) *

Dating Atlantis

Dating Atlantis is one of the most contentious difficulties faced by Atlantology. The critical problem is to identify the time of the Atlantean War and that of the later destruction of Atlantis itself; two events possibly separated by a period not recorded by Plato. This entry is primarily concerned with the date of the war. However, it should be pointed out that Plato also reveals that the Atlantis story has a very long history before the war, back to a time when ships and sailing did not yet exist (Crit.113e), so it is understandable when Plato filled that historical gap with mythological characters, namely five sets of twins sired by Poseidon. Of course, Poseidon being a sea god did not require a boat to get to the island of Atlantis! Plato also informs us that the twins and their descendants lived on the island for ‘many generations’ and extended their rule over many other islands in the sea (Crit.114c).

There are roughly three schools of thought regarding this important detail. The first group persists in accepting at face value Plato’s reference to a period of 9,000 solar years having elapsed since the War with Atlantis up to the time of Solon’s visit around 550 BC. The second group is convinced that the 9,000 refers to periods other than solar years, such as lunar cycles or seasons. The third group seeks to identify the time of Atlantis by linking it to other known historical events.

While these groups offered some level of evidence, however flimsy, to support their claims, some individuals have placed Atlantis up to millions of years in the past based on nothing more than their fertile imaginations or delusions. Arguably the best-known was Edgar Cayce, but purveyors of such daft ideas are still lurking among us!(m)

>Rene Malaise writing in Egerton Sykes‘ Atlantis journal (#108, January/February 1967, Vol. 20 No. 1) challenged the idea that Plato’s 9,000 years was a reference to years of 12 months. Atlantisforschung has now republished the article in German and I have added an English translation below(s).<

Desmond Lee has commented[0435] that “the Greeks, both philosophers and others…….seem to have been curiously lacking in their sense of time-dimension.”

[1.0] 9550 BC is factually correct

This view has a slowly dwindling number of supporters among serious investigators. Massimo Rapisarda is one such promoter, who has offered his reasons for accepting this early date(p). To support this idea proponents usually cite a wide range of evidence to suggest the existence of advanced cultures in the 10th millennium BC. Matters such as an earlier than conventionally accepted date for the Sphinx, early proto-alphabets a la Glozel or the apparently anomalous structures such as the Lixus foundations or the controversial Baalbek megaliths have all been recruited to support an early date for Atlantis, many, if not all, have their dates hotly disputed. Apart from the contentious dates, there is NOTHING to definitively link any of them with Plato’s Atlantis.

In common with most nations, the Egyptians competitively promoted the great antiquity of their own origins. Herodotus reports that while in Egypt he was told of a succession of kings extending over 17,000 years. The priests of Memphis told him firmly that 341 kings and a similar number of high priests had until then, ruled their country. (Herodotus, Book II, 142). ), of course, there is not a shred of archaeological evidence to support such a claim. Even an average reign of 20 years would give a total of nearly 7000 years whereas a more improbable 26-year average would be required to span the necessary 9000 years.

It is therefore obvious that the 17,000 years related to Herodotus is not credible raising a question regarding the trustworthiness of the 9000 years told to Solon.

In The Laws Plato refers to Egyptian art going back 10,000 years, seemingly, indicating consistency in his belief in the great antiquity of civilisation and fully compatible with his date for Atlantis. However, I have discovered that in Plato’s time ‘ten thousand’ was frequently used simply to express a large but indefinite number.

A Bible study site tells us that “The use of definite numerical expressions in an indefinite sense, that is, as round numbers, which is met with in many languages, seems to have been very prevalent in Western Asia from early times to the present day.”(h)

The acceptance of Plato’s 9,000 years as literally correct defies both commonsense and archaeological evidence, which demonstrates that neither Athens nor a structured Egypt existed at such an early period. The onus is on those, who accept the prima facie date of 9,600 BC, to explain how Atlantis attacked a non-existent Athens and/or Egypt.

A major difficulty in accepting Plato’s 9,000 years at face value is that it conflicts with our current knowledge of ancient seafaring. Professor Seán McGrail (1928-2021) wrote in his monumental work, Boats of the World “There is no direct evidence for water transport until the Mesolithic even in the most favoured regions, and it is not until the Bronze Age that vessels other than logboats are known” [1949.10]. Wikipedia’s list of ancient boats supports this view(r). For those that adhere to a 10th millennium BC date for the Atlantean War with Athens, this lack of naval evidence to support such an early date undermines the idea. An invasion fleet of canoes travelling from beyond the Pillars of Herakles to attack Athens or Egypt seems rather unlikely!

Even more incongruous is Plato’s description of horse baths (Crit.117b), a facility that was highly unlikely around 9600 BC, when you consider that this is probably millennia before the domestication of horses.

In a 2021 article(h) concerning 10,000 BC, Thorwald C. Franke offered the following opinion; “Many scientists seem to live quite comfortably with Graham Hancock and similar authors speculating about 10,000 BC because these hypotheses are so nonsensical that they do not interfere with real science. Sometimes you have the impression that many scientists even prefer such misleading popular errors over more informed hypotheses because they would make the audience ask more serious questions and then the questions could not be dismissed so easily anymore. But this is only an impression. In truth, scientists shy away from the effort to overcome these popular errors. It is much easier to stay silent and to ignore them.”

Alexandros Angelis wrote(q) of how he is “always suspicious of coincidence. Whenever I hear this word, an alarm sets off in my head. In my book ‘Our Unknown Ancient Past: Thoughts and Reflections on the Unexplained Mysteries of Prehistory’ I state that it cannot be a coincidence that Plato’s date of Atlantis’ destruction (9.600 BC) is spot on, coinciding with the abrupt end of the Younger Dryas (9.600 BC).”

When I first encountered this ‘coincidence’ I was also suspicious. However, as I investigated further I realised that all of Plato’s large numbers seemed to be inflated by what was arguably a common factor – another coincidence? I have devoted an entire chapter in Joining the Dots to this problem.

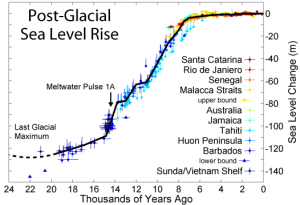

Angelis considers the ‘rapid’ gradual melting of the ice at the end of the Younger Dryas as the cause of Atlantis’ submergence, which might have been true except that Plato tells us that the catastrophe took place over a day and a night and that the event was triggered by an earthquake. Angelis seems unaware that isostatic rebound is a very slow process of readjustment involving centuries and sometimes thousands of years and even when glaciers melt rapidly, sea levels, because of the vastness of our oceans, rise slowly.

[2.0] 9000 refers to units of time other than solar years

Advocates of this view, understandably point out, that the Atlantis described in such detail by Plato belongs to the Bronze Age and could not have existed at an earlier date. It is worth noting that the technology is coincidental with the most advanced known to Plato and his audience. For those who argue that mankind has been destroyed on one or more occasions and has had to start again from scratch, it is not credible that if this was the case, the culture and technology described by Plato as existing in 9500 BC is precisely what he would have experienced himself. There is nothing in the Atlantis texts to connect it with a pre-Bronze Age society, nor is there anything to suggest any technology or cultural advance beyond that of the 4th century BC. Plato’s tale tells of the existence of at least three major nations before the destruction of Atlantis: Egypt, Athens and Atlantis itself. There is no archaeological evidence to indicate anything other than Neolithic cultures existing in Egypt or Athens around 9500 BC. The currently accepted date for the beginning of Egyptian civilisation is circa 3100 BC and also for the existence of a primitive culture around Athens at about the same time. This would parallel the time of the Western European megalithic builders.

It is noteworthy that researchers who support a 9,600 BC date for the war between Atlantis and Athens cannot explain how this took place millennia before there was any structured society in Greece or Egypt.

It may be worth noting the comments of Israel Finkelstein and Neil Silberman who have argued[280] for a 7thcentury BC date for the final draft of the Exodus narrative rather than during the 2nd millennium BC as suggested by the text. “In much the same way that European illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages depicted Jerusalem as a European city with turrets and battlements to heighten its direct impact on contemporary readers” (p68). Similarly, it is possible that Plato added architectural and technological details of his day to a more ancient tale of a lost civilisation to make a more powerful impression on his audience.

According to Bury’s translation, Plato mentions (Crit. 119e) that iron was used for utensils and weapons in Atlantis and so forcing us to look to a date later than 2000 BC for its destruction. Olaf Rudbeck drew attention to this reference around 1700.

[2.1]

Diaz-Montexano claims that the ‘9000 years’ in Critias has been mistranslated. He refers to the earliest versions of Critias that are available and insists that the texts permit a translation of either ‘9 times in a 1000 years’ or ‘1009’, the first being the more rational! Frank Joseph has also used this 1009 number, quoting private correspondence from Kenneth Caroli, in his 2015 regurgitation[1074] of Atlantis and 2012. Diaz-Montexano has also drawn attention to the commentary on Timaeus by Proclus, writing in the 5th century AD, where he treats Plato’s use of 9000 as having symbolic rather than literal meaning. It should also be kept in mind that many cultures, ancient and modern use specific numbers to indicate indefinite values(e). In a more recent paper, Diaz-Montexano concluded that “we can place their military and colonizing expansion towards the end of 3.500 BC, at the earliest, and the end of their civilization (with Atlantis sinking) between 2.700 and 1.700 BC.”(o)

[2.2] In June 2017, a forum on the Historum.com website included the following possible explanation for the Atlantean dates:

“ The date 8000 is given as a fraction of 8 since the Greeks commonly used fractional notation. Plato wrote in 400 BC and Solon obtained the account in 570 BC.

No Egyptian Annals ever went back 9000 or even 8000 years. The furthest back the Egyptian annals went at the time of Herodotus was to 3050 BC to the reign of Menes the first Pharaoh who Herodotus knew about. Therefore it is obvious that the number of years has been given as a fraction which was extremely common in Greek numerology.

Thus the war between Atlantis and Athens occurred in 9000/8 + 570 = 1695 BC (+/-63 years) which is pretty close to the date of the war between the Titans and the Gods c.1685-1675 BC. The entire story of Atlantis runs concurrent to the time of the Thera Eruption. You even have 10 kings ruling the land equivalent to the 12 Titans.”

The Bible too denotes years as fractions, i.e. seasons, equinoxes/solstices etc. That is why you have biblical patriarchs that lived 800 and 900 years old. The ages to Noah are all counted in Lunar months.”(i)

While I’m aware that the Egyptians also had a different way of dealing with fractions, I really cannot fully understand any of the suggestions made above.

[2.3] 900, not 9000 years

To address these apparent dating problems, some have suggested that the stated 9000 years, which allegedly elapsed since the catastrophe, are the result of incorrect transcription by someone along what is a very long chain of transmission and that hundreds have somehow been confused with thousands and that the correct figure should be 900 years. Another suggestion is that the Egyptian hieroglyphics for ‘hundred’ and ‘thousand’ are easily confused. This explanation does not hold water, as there is little room for confusion between these hieroglyphics as illustrated below. This idea has been adopted by Don Ingram and incorporated into his Atlantis hypothesis.

Immanuel Velikovsky also endorsed the idea of a tenfold discrepancy in Plato’s date for the time of Atlantis in Worlds in Collision [037.152].

However, 900 years earlier than Solon would place the conflict with the Atlanteans during the XVIIIth Dynasty and would have been well recorded. More recently Diaz-Montexano put forward the idea that the Egyptian words for ‘100’ and ‘1000’ when spoken sounded similar leading to Solon’s error. This idea has now been taken up by James Nienhuis and in greater detail by R. McQuillen(a).

Another explanation offered by James W. Mavor Jnr. is that the original Egyptian story emanated from Crete where it may have been  written in either the Linear A or Linear B script where the symbols for 100 and 1000 are quite similar. In both scripts, the symbol for 100 is a circle whereas the symbol for 1000 is a circle with four equally spaced small spikes or excrescences projecting outward.

written in either the Linear A or Linear B script where the symbols for 100 and 1000 are quite similar. In both scripts, the symbol for 100 is a circle whereas the symbol for 1000 is a circle with four equally spaced small spikes or excrescences projecting outward.

Nevertheless, the most potent argument against the ‘factor ten’ solution is that if the priests did not intend to suggest that Egypt was founded 8000 years before Solon’s visit but had meant 800 years, it would place the establishment of Egypt at around 1450 BC, which is clearly at variance with undisputed archaeological evidence. However, I contend that they were referring to the establishment of Sais as a centre of importance, not the foundation of the entire nation of Egypt.

In Joining the Dots, I supported the ‘factor ten’ explanation but did so because all of Plato’s large numbers relating as they do to dimensions, manpower and time invariably appear to be exaggerations, but become far more credible when reduced by a factor of ten. Supporters of Plato’s 9,000 years as factual seem to ignore all the other numbers that also appear to be seriously inflated!

[2.4] 9000 months not years

The earliest suggestion that I have found which implied that the age of Atlantis noted by Plato referred to months rather than solar years comes from the early fourteenth century.

Thorwald C. Franke has drawn attention to Thomas Bradwardine‘s rejection of Plato’s, or more correctly the Egyptian priest’s, apparent claim of a very early date for Atlantis [1255.242]. It seems that he found such a date conflicted with biblical chronology. In the end, he proposed that Plato’s ‘years’ were lunar cycles. Similarly, Pierre d’Ailly (1350-1420), a French theologian who became cardinal, arrived at the same conclusion for similar reasons.

Around two and a half centuries later in 1572 Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa suggested the application of lunar ‘years’ rather than solar years to Plato’s figures. Augustin Zárate expressed the same view in 1577, quoting Eudoxus in support of it.

In the 18th century, Cornelius De Pauw also believed that Plato’s 9000 ‘years’ was a reference to lunar cycles.

Then there are others, such as Émile Mir Chaouat and Jürgen Hepke who also subscribe to the view that the 9000 ‘years’ recorded by Plato referred to months rather than solar years, as the early Egyptians extensively used a lunar calendar and continued to use it throughout their long history, particularly for determining the dates of religious festivals and since Solon received the Atlantis story from Egyptian priests it would be understandable if they used lunar ‘years’ in their conversations. Eudoxus of Cnidos (c.400 BC- c. 350 BC), a mathematician and astronomer, who spent a year in Egypt, declared, “The Egyptians reckon a month as a year”. Diodorus Siculus (1st cent. BC) echoes this statement. (see Richard A. Parker[682]) and Manetho (3rd cent.BC) (Aegyptiaca[1373.40])

Olof Rudbeck also proposed that Plato misunderstood the Greek priesthood’s use of lunar cycles rather than solar years to calculate time. This in turn led him to date the Atlantean War to 1350 BC.

Robert Argod wrote [065.254] “This story, which was supposedly related to Solon by Egyptian priests, speaks of 8,000 years, which are certainly in fact moons – for this was how the Egyptians counted. This dates the story reasonably accurately to the 13th century BC, at the memorable period of the battles between Rameses II and Rameses III against the Sea Peoples.” A coincidence?

This use of months rather than years would give us a total of just 750 years before Solon’s visit and so would place the Atlantis catastrophe around 1300 BC, nearly coinciding with the eruption of Thera and the collapse of the Minoan civilisation.

A similar explanation has been offered by J.Q. Jacobs to rationalise the incredible time spans found in ancient Indian literature, who suggested that numbers referred to days rather than years(b).

Stefan Bittner seemed to date the Atlantean War in 1644 BC using a combination of treating Plato’s years as months and reducing the same years by a factor of ten!

Even more bizarre is the suggestion from Patrick Dolciani that Plato’s 9000 ‘years’ were in fact periods of 73 days because it agrees with both the synodical revolution of Venus and our solar year!!

[2.5] 5,000 not 9,000 years

A claim was made on Graham Hancock’s website in 2008(c) that Plato did not write 9,000 but instead wrote 5,000, but that the characters for both were quite similar leading to the misunderstanding. This claim was originally made by Livezeanu Mihai. However, my reading of Greek numerals makes this improbable as 9,000 requires five characters ( one for 5,000 and one for each of the other four thousand), while 5,000 needs just one.

Adrian Bucurescu claims that Plato originally said 5,000, not 9,000 years had elapsed between the Atlantean war and Solon’s visit to Egypt. He bases this claim on the fact that the works of the Greek philosophers were preserved in Arabic translations after the fall of Constantinople and that their numbers ‘5’ and ‘9’ were sufficiently similar to have led to a transcription error!(b) This is difficult to accept as the Arabic character for nine is rather like our ‘9’, while the Arabic five is like our zero!

[3.1] Sometime after 9500 BC.

Jonas Bergman correctly points out that according to the story related by the priests of Sais to Solon, the Egyptian civilisation was founded 1000 years after Athens was first established in 9600 BC. Although this probably just refers to the founding of the city of Sais rather than the early Egyptian state.

Plato describes the original division of the earth between the gods of old, Poseidon got Atlantis and Athena got Greece. The implication is that both were founded at the same time, namely in 9600 BC. Realistically, the 9000-year time span is better treated as an introductory literary cliché such as ‘once upon a time’ or the Irish ‘fado, fado’ (long, long ago). Plato’s text describes the building of Atlantis and informs us that no man could get to the island ‘for ships and voyages were not yet’. Since Atlantis had twelve hundred warships at the time of the conflict with Athens, the war could not have taken place in 9600 BC. The development of seafaring and shipbuilding would have taken considerable time. Bergman concludes that the war with Atlantis took place long after 9600 BC.

Another date was proposed by Otto Muck [098] in 1976 when he maintained that Atlantis had been situated in the Atlantic and was destroyed by an asteroidal impact in 8498 BC and proposed that the same event also created the Carolina Bays!

Felipoff, a Russian refugee living in Algiers presented a paper to the French Academy of Sciences in which he claimed to have astronomically calculated the exact date of the destruction of Atlantis as 7256 BC! Felipoff has been described as an astronomer whose ideas received some attention around the 1930s, apart from which little else is known about him.

[3.2] Peter James as quoted in Francis Hitching’s The World Atlas of Mysteries[307.138] is reported to have accepted the orthodox date of 3100 BC as the start of Egyptian civilisation and considering the priest’s statement that the events outlined took place one thousand years before the creation of Egypt and so added only 500 years to compensate for nationalistic exaggeration and has concluded that 3600 BC is a more realistic date for the destruction of Atlantis.

[3.3] Early in the 20th century, the German scholar Adolf Schulten and the classicist H. Diller from Kiel, both advocated an even more radical date of around 500 BC, having identified the narrative of Plato as paralleling much of the Persian wars (500-449 BC) with the Greeks. This however would be after Solon’s trip to Egypt and have made little sense of Plato’s reference to him.

[3.4] 4015 BC is the precise date offered by Col. Alexander Braghine who credits the destruction of Atlantis to a close encounter with Halley’s Comet on the 7th of June in that year. This is close to the date favoured by de Grazia.

[3.5] 3590-1850 BC has been suggested by the Czech writer Radek Brychta who has developed an ingenious idea based on the fact that the Egyptians who were so dependent on the Nile, divided their year into three seasons related to their river, the flooding, the blossom and the harvest periods. Brychta points out that counting time by seasons rather than solar years was common in the Indus civilisation that occupied part of modern Pakistan. Even today Pakistan has three seasons, cool, hot and wet. Brychta contends that the 9000 ‘years’ related to Solon were in fact seasons and should be read by us as 3000 years which when added to the date of Solon’s Egyptian visit would give an outside date of 3590 BC. If Brychta is correct this 9000-year/season corruption could easily have occurred during the transmission and translation of the story during its journey from the Indus to the Nile valley.

In the 18th century, Samuel Engel also interpreted Plato’s 9,000 years as a reference to seasons of four months each. (See: Axel Hausmann)

[3.6] 3100 BC as a date for the destruction of Atlantis has been proposed by several investigators including, David Furlong, Timo Niroma, and Duncan Steel. Hossam Aboulfotouh has proposed a similar 3070 BC as the date of Atlantis’ demise(f).

[3.7] 2200 BC is the proposed date put forward by Dr Anton Mifsud for the end of Atlantis, located in the vicinity of his native Malta. He arrived at this conclusion after studying the comments of Eumelos of Cyrene who dated the catastrophe to the reign of King Ninus of Assyria. Around the same time, in Egypt, unusually low Nile floods led to the collapse of centralised government and generations of political turmoil(f). According to some commentators(g), the Los Millares culture in Iberia also ended around the same time.

[3.8] Circa 1200 BC is a date favoured by investigators such as Eberhard Zangger [483] and Steven Sora [395] who both identify the Atlantean War with the Trojan War. Frank Joseph is more precise proposing that “it appears, then, that the destruction of Atlantis took place around the first three days of November 1198 BCE. [102.208]. It may be worth noting that this date has also been linked to the suggested close encounter with the Phaëton comet and its destructive effects globally.

[3.9] Stelios Pavlou has taken a different approach, basing his conclusion on a close analysis of the Egyptian King Lists with particular reference to that of Manetho. Pavlou’s paper is well(l) worth studying. In the end, he contends that the time of Atlantis was in or around 4532 BC.

[4.0] More than one Atlantis!

It is not unreasonable to consider Plato’s Atlantis narrative as a literary amalgam of two or more historically based stories or myths. One possibility is that the Egyptian priests related to Solon the tale of the inundation of a powerful and advanced culture in the dim and distant past. Such an event did occur, worldwide, when the Ice Age glaciers melted, resulting, for example, in the eastern Atlantic, the flooding of the North Sea, the Celtic Shelf and dramatically reducing in size of the Canaries and the Azores and creating the British Isles. The entire world was affected by this event so there were also major inundations in the West Indies and the South China Sea. However, events off the coasts of Europe and Africa would be more likely to become part of folklore on this side of the Atlantic.

Over 70 years ago, Daniel Duvillé suggested, that there had been two Atlantises, one in the Atlantic and the other in East Africa.

[5.0] My preference is to treat the use of 9000 by Solon/Plato as an expression of a large but indefinite number or an exaggeration by a factor of ten. At the beginning of my research, I strongly favoured the former, but as I proceeded to investigate other aspects of Plato’s Atlantis story, I realised that virtually all other large numbers used by him also appeared to be inflated by a comparable amount. In seeking a solution to this I found myself drawn to Occam’s Razor, which states that where there are competing theories, the simpler is to be preferred.

It is worth noting that the Egyptian hieratic numerals also stopped with the highest value, expressed by a single character, being 9000. However, having studied the matter more closely I am reluctantly drawn to the ‘factor ten’ theory. This I have written about at some length in Joining the Dots.

The 1st millennium BC saw the introduction and gradual development of new writing and numerical systems by the Greeks. Some claim that the Greeks borrowed the Egyptian numbers(k).

At an early stage, 9000 was the highest number expressed by a single character in Greek, which in time came to be used to denote a large but uncertain value. As the needs of commerce and science demanded ever higher numbers a new character ‘M’ for myriad with a value of 10,000 was introduced. It also was used to indicate a large indefinite number, a practice that continues to this very day. Greek numerical notation was still being developed during Plato’s life.

Today, we use similar expressions such as ‘I have a million things to do’ with no intention of being taken literally, but simply to indicate ‘many’(e). Unfortunately, this interpretation of 9,000 does little to pinpoint the date of the Atlantean war, but it is not unreasonable to attribute a value to it of something above 1,000 and possibly a multiple of it.

Diaz-Montexano has drawn attention to the writings of Proclus, who in his commentary on Timaeus declared the number 9,000 to have had a symbolic value (Timaeus 45b-f).

However, having said that, I am also attracted to the ’factor ten’ theory after a study of other numbers in the Atlantis narrative which all seem to be consistently exaggerated by a similar amount, which seems to be a factor of ten!

Andrew Collins in his Gateway to Atlantis[072.52] wrote “a gross inconsistency has crept into the account, for although Critias affirms that Athens’ aggressor came from ‘without’ the Pillars of Hercules, the actual war is here said to have taken place ‘nine thousand years’ before the date of the dialogue, c.421 BC. This implies a date in the region of 9421 BC, which is not what was stated in the Timaeus. Here 9000 years is the time that has elapsed between the foundation of Athens and Solon’s visit to Sais c. 570 BC. Since Egypt was said to have been founded a full thousand years later, and the ‘aggressor’ rose against both Athens and Egypt, it provides a date post 8570 BC. These widely differing dates leave us with a glaring anomaly that defies explanation. The only obvious solution is to accuse Plato of a certain amount of sloppiness when compiling the text.”

Collins’ suggestion of ‘sloppiness’ is made somewhat redundant if my suggestion that Plato was using 9,000 as a large but indefinite idiomatic value, could be substantiated.

The late Ulf Richter was quite unwilling to accept Plato’s 9,000 years as reliable after a close study of the relevant texts.

Others have produced evidence to suggest that this period in the Earth’s history saw one or more major catastrophic events that may or may not have been interconnected; (i) a collision or near-miss with an extraterrestrial body, (ii) a pole shift, (iii) the melting of the glaciers of the last Ice Age and the consequent raising of sea levels worldwide. This rise provides a credible mechanism that could account for the ’sinking’ of Atlantis.

Mary Settegast, an archaeological researcher, has defended the early date of Atlantis with a remarkable book[545] that delves extensively into Mediterranean and Middle Eastern prehistory and mythologies.

(a) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20181215223457/https://gizacalc.freehostia.com/Atlantis.html

(b) http://www.jqjacobs.net/astro/aryabhata.html

(c) https://www.grahamhancock.com/phorum/read.php?f=1&i=249446&t=249446

(d) https://www.unexplained-mysteries.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=255909

(e) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indefinite_and_fictitious_numbers

(f) Archive 2668 | (atlantipedia.ie) *

(g) https://www.minoanatlantis.com/Origin_Sea_Peoples.php

(h) https://www.biblestudytools.com/dictionary/number/

(i) https://historum.com/speculative-history/128055-atlantis-truth-myth-3.html

(j) https://web.archive.org/web/20100708140347/www.fotouh.netfirms.com/Aboulfotouh-Atlantis.htm

(k) https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3109806.stm

(m) https://matthewpetti.com/atlantis/

(n) Do you believe in 10,000 BC? – Atlantis-Scout

(p) http://cab.unime.it/journals/index.php/AAPP/article/view/AAPP.932C1/AAPP932C1

(q) https://ourunknownancientpast.blogspot.com/2021/08/plato-atlantis-probability-of.html

(r) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_oldest_surviving_ships

(s) Dating the Atlantis catastrophe – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog) *

Orichalcum

Orichalcum is, according to legend, reputed to have been ‘invented’ by Cadmus noted in Greek mythology as the legendary Phoenician founder of Boeotian Thebes. This metal is one of the many mysteries in Plato’s Atlantis narrative. It is mentioned five times in the Critias [114e, 116c-d, 119c] as a metal extensively used in Atlantis. I am not aware of any reference to it anywhere else in his writings, a fact that can be advanced as evidence of the veracity of his Atlantis story. Plato took the time to explain to his audience why the kings of Atlantis have Hellenised names. However, he introduces Orichalcum into the story without explanation, which suggests that the metal was something well-known to the listeners. It is therefore natural to expect that metals might play an important part in determining the credibility of any proposed Atlantis location.

Bronze was an alloy of copper and tin, while brass was a mixture of copper and zinc, their similarity is such that museums today refer to artefacts made of either refer to them as copper alloys.

According to James Bramwell[195.91], Albert Rivaud demonstrated that the term ‘orichalcum’ was known before Plato and not just invented by him. Similarly, Zhirov notes that both Homer and Hesiod refer to the metal[0458.46], as does Ibycus, the 6th century BC poet, who compares its appearance to gold suggesting a brasslike alloy. Thomas Taylor (1825) noted that in a fragment from a lost book of Proclus, he seems to refer to orichalcum under the name of migma(c).>Virgil in his Aeneid mentioned that the breastplate of Turnus was “stiff with gold and white orachalc”.<

Wikipedia also adds that “Orichalcum is also mentioned in the Antiquities of the Jews – Book VIII, sect. 88 by Josephus, who stated that the vessels in the Temple of Solomon were made of orichalcum (or a bronze that was like gold in beauty). Pliny the Elder points out that the metal had lost currency due to the mines being exhausted. Pseudo-Aristotle in ‘De mirabilibus auscultationibus’ describes orichalcum as a shining metal obtained during the smelting of copper with the addition of ‘calmia’, a kind of earth formerly found on the shores of the Black Sea, which is attributed to be zinc oxide.”

Friedrich Netolitzky (1875-1945) offered an independent interpretation of the oriharukon (orichalcum) in Plato’s Atlantis account, which he identified as an artificial modification of white gold (known as Asem in ancient Egypt).

Atlantisforschung also offers a lengthy article on orichalcum(p).

Orichalcum, or its equivalent Latin Aurichalcum, is usually translated as ‘golden copper’ referring to either its colour or composition (80% copper and 20% zinc) or both. However, Webster’s Dictionary translates it as ‘mountain-copper’ from ‘oros’ meaning mountain and ‘chalchos’ meaning copper.

Sir Desmond Lee described the metal as ‘imaginary’ without explaining away the classical references or the fact that ”In numismatics, orichalcum is the name given to a brass-like alloy of copper and zinc used for the Roman sestertius and dupondius(r). Very similar in composition to modern brass, it had a golden-yellow color when freshly struck. In coinage, orichalcum’s value was nearly double reddish copper or bronze. Because production cost was similar to copper or bronze, orichalcum’s formulation and production were highly profitable government secrets.”(m)

Modern writers have offered a range of conflicting explanations for both the origin and nature of orichalcum. A sober overview of the subject is provided by the Coin and Bullion Pages website(d).

In 1926 Paul Borchardt recounted Berber traditions that recalled a lost City of Brass. Salah Salim Ali, the Iraqi scholar, points[0077] out that a number of medieval Arabic writers referred to an ancient ‘City of Brass’ echoing the Orichalcum-covered walls of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ivan Tournier, a regular contributor to the French journal Atlantis proposed that orichalcum was composed of copper and beryllium. Tournier’s conclusion seems to have been influenced by the discovery in 1936 at Assuit in Egypt of a type of scalpel made from such an alloy(e). An English translation of Tournier’s paper was published in Atlantean Research (Vol 2. No.6, Feb/Mar.1950). In the same edition of A.R. Egerton Sykes adds a few comments of his own on the subject(r).

An unusual suggestion was made by Michael Hübner who noted that “small pieces of a reddish lime plaster with an addition of mica were discovered close to a rampart” in his chosen Atlantis location of South Morocco. He links this with Plato’s orichalcum but does so without any great enthusiasm.

Jim Allen, promoter of the Atlantis in Bolivia theory, claims that a natural alloy of gold and copper is unique to the Andes. Tumbaga is the name given by the Spaniards to a non-specific alloy of gold and copper found in South America. However, an alloy of the two that has 15-40% copper, melts at 200 Co degrees less than gold. Dr. Karen Olsen Bruhns, an archaeologist at San Francisco State University wrote in her book, Ancient South America[0497], “Copper and copper alloy objects were routinely gilded or silvered, the original colour apparently not being much valued. The gilded copper objects were often made of an alloy, which came to be very important in all of South and Central American metallurgy: tumbaga. This is a gold-copper alloy that is significantly harder than copper, but which retains its flexibility when hammered. It is thus ideally suited to the formation of elaborate objects made of hammered sheet metal. In addition, it casts well and melts at a lower temperature than copper, always a consideration when fuel sources for a draught were the wind and men’s lungs. The alloy could be made to look like pure gold by treatment of the finished face with an acid solution to dissolve the copper, and then by hammering or polishing to join the gold, giving a uniformly gold surface”.

Enrico Mattievich also believed that orichalcum had been mined in the Peruvian Andes(b).

Jürgen Spanuth tried to equate Orichalch with amber. Paul Dunbavin links Orichalcum with Wales. Robert Ishoy implies a connection between obsidian and Orichalcum, an idea also promoted by Christian & Siegfried Schoppe.

The most exotic suggestion has come from Felice Vinci who equates it with platinum[019.286] which was probably brought from the Ural Mountains. The most recent (2023) identification of orichalcum, which Plato tells us was used as wall cladding in Atlantis, came from Graham Phillips who also suggested[2063] that it was platinum! Incidentally, platinum was not discovered by Europeans until the eighteenth century in South America.

Albert Slosman thought that there was a connection between Moroccan oricalcita, a copper derivative, and Plato’s orichalcum. Peter Daughtrey has offered [893.82] a solution from a little further north in Portugal where the ancient Kunii people of the region used ori or oro as the word for gold and at that period used calcos for copper.

Thorwald C. Franke has suggested[750.174] that two sulphur compounds, realgar and orpiment whose fiery and sometimes translucent appearance might have been Plato’s orichalcum. His chosen location for Atlantis, Sicily, is a leading source of sulphur and some of its compounds. I doubt this explanation as realgar disintegrates with prolonged exposure to sunlight, while both it and orpiment, a toxin, could not be described as metals in any way comparable with gold and silver as stated by Plato.

Frank Joseph translates orichalcum as ‘gleaming or superior copper’ rather than the more correct ‘mountain copper’ and then links Plato’s metal with the ancient copper mines of the Upper Great Lakes. Joseph follows Egerton Sykes in associating ‘findrine’, a metal referred to in old Irish epics, with orichalcum. However, findrine was usually described as white bronze, unlike the reddish hue of orichalcum.

Ulf Erlingsson suggested [319.61] that orichalcum was ochre, which is normally yellow, but red when burnt. He seems to have based this on his translation of the text Critias116b. In fact, the passage describes the citadel flashing in a fiery manner, but it does not specify a colour!

Other writers have suggested that orichalcum was bronze, an idea that conflicts with a 9600 BC date for the destruction of Atlantis since the archaeological evidence indicates the earliest use of bronze was around 6000 years later.

Thérêse Ghembaza has kindly drawn my attention to two quotations from Pliny the Elder and Ovid that offer possible explanations for Plato’s orichalcum(n). The former refers to a Cypriot copper mixed with gold which gave a fiery colour and is called pyropus, while Ovid also refers to a cladding of pyropus. She also mentions auricupride(Cu3Au), an alloy that may be connected with orichalcum.

Zatoz Nondik, a German researcher, has written a book about Plato’s ‘orichalcum’, From 2012 to Oreichalkos[0841], in which he describes, in detail, how the orichalcum may be related to Japanese lacquer and suitable for coating walls as described in the Atlantis(b) narrative!

The fact is that copper and gold mixtures, both natural and manmade, have been found in various parts of the world and have been eagerly seized upon as support for different Atlantis location theories. A third of all gold is produced as a by-product of copper, lead, and zinc production.

It is also recorded that on ancient Crete, in the Aegean, two types of gold were found, one of which was a deep red developed by the addition of copper. Don Ingram suggests that the reddish gold produced in ancient Ireland is what Plato was referring to.

Irrespective of what orichalcum actually was, I think it is obvious that it was more appropriate to the Bronze Age than 9,600 BC. Furthermore, it occurs to me that Plato, who was so careful to explain or Hellenise foreign words so as not to confuse his Athenian audience, appears to assume that orichalcum is not an alien term to his audience.

The result of all of this is that Orichalcum has been advanced to support the location of Atlantis in North and South America, Sundaland, Ireland, Britain and the Aegean. Once again an unintentional lack of clarity in Plato’s text hampers a clear-cut identification of the location of Atlantis.

A fascinating anecdote relating to the use of a term similar to ‘orichalcum’ to describe a mixture of copper and gold was used by a metalsmith in Dubai as recently as 2007 and is recounted on the Internet(a).

The Wikipedia entry(f) for ‘orichalcum’ adds further classical references to this mysterious metal.

2015 began with a report that 47 ingots of ‘orichalcum’ had been found in a shipwreck off the coast of Sicily, near Gela, and dated to around 600 BC(g). What I cannot understand is that since we never knew the exact composition of Plato’s alloy, how can anyone today determine that these salvaged ingots are the same metal? Thorwald C. Franke has more scholarly comments on offer(h). Jason Colavito has also applied his debunking talents to the subject(i). In June of the same year,

2015 began with a report that 47 ingots of ‘orichalcum’ had been found in a shipwreck off the coast of Sicily, near Gela, and dated to around 600 BC(g). What I cannot understand is that since we never knew the exact composition of Plato’s alloy, how can anyone today determine that these salvaged ingots are the same metal? Thorwald C. Franke has more scholarly comments on offer(h). Jason Colavito has also applied his debunking talents to the subject(i). In June of the same year,  Christos Djonis, in an article(j) on the Ancient Origins website, wrote a sober review of the media coverage of the shipwreck. He also added some interesting background history on the origin of the word ‘orichalcum’.

Christos Djonis, in an article(j) on the Ancient Origins website, wrote a sober review of the media coverage of the shipwreck. He also added some interesting background history on the origin of the word ‘orichalcum’.

An analysis revealed(k) that those ingots were composed of 75-80% copper, 15-20% zinc, and traces of nickel, lead and iron, but no proof that this particular alloy was orichalcum. The recovery of a further 39 ingots from the wreck was reported in February 2017 and the excavation of the sunken ship continues.

An extensive paper(o) on the Gela discovery reported: “that Professor Sebastiano Tusa, an archaeologist at the office of the Superintendent of the Sea in Sicily, claimed the metal they had discovered in the remains of the ship was probably the mythical and highly prized red metal orichalcum.” However, dissent was not long coming, as the paper also notes that “ Enrico Mattievich, a former physics professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, believes the metal has its origins in the Chavin civilisation that developed in the Peruvian Andes in around 1,200 BC. He claims the metal alloy is made from copper, gold and silver. He claims that the discovery off the coast of Gela is not true orichalcum.” I think that both are probably wrong as we do not know the exact chemical composition of Plato’s orichalcum and both are just engaging in speculation.

The most recent explanation for the term comes from Dhani Irwanto who has proposed that orichalcum refers to a form zircon(l) that is plentiful on the Indonesian island of Kalimantan, where he has hypothesised that the Plain of Atlantis was located [1093.110].

(a) Problems with Atlantis – Aquiziam (archive.org)

(b) https://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?year=2011&id=268

(c) https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/flwp/flwp26.htm

(d) https://www.coinandbullionpages.com/gold-alloys/orichalcum.html

(e) Atlantis Research Vol 2. No.6, Feb/Mar 1950, p.86

(f) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orichalcum

(g) See: Archive 2460

(h) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_newsl_archive.htm

(k) From Fiction to Fact: Ancient Metal Identified with XRF – Analyzing Metals (archive.org) *

(l) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zircon

(m) https://www.forumancientcoins.com/numiswiki/view.asp?key=orichalcum

(n) See: Archive 3456

(p) Oriharukon – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(q) http://www.oocities.org/motorcity/factory/2583/orich.htm

(r) http://www.jaysromanhistory.com/romeweb//engineer/art11.htm

Shoals of Mud

A Shoal of mud is stated by Plato (Tim.25d) to mark the location of where Atlantis ‘settled’. He described these shallows in the present tense, clearly implying that they were still a maritime hindrance in Plato’s day.

Three of the most popular translations clearly indicate this:

….the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.

…..the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal of mud which the island created as it settled down.”

…..the sea in that area is to this day impassible to navigation, which is hindered by mud just below the surface, the remains of the sunken island.

>Wikipedia has noted(h) that “during the early first century, the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo wrote about the destruction of Atlantis in his On the Eternity of the World, xxvi. 141, in a longer passage allegedly citing Aristotle’s successor Theophrastus.

‘ And the island of Atalantes [translator’s spelling; original: “????????”] which was greater than Africa and Asia, as Plato says in the Timaeus, in one day and night was overwhelmed beneath the sea in consequence of an extraordinary earthquake and inundation and suddenly disappeared, becoming sea, not indeed navigable, but full of gulfs and eddies’.”<

Since it is probable that Atlantis was destroyed around a thousand years or more before Solon’s Egyptian sojourn, to have continued as a hazard for such a period suggests a location that was little affected by currents or tides. The latter would seem to offer support for a Mediterranean Atlantis as that sea enjoys negligible tidal changes, as can be seen from the chart below. The darkest shade of blue indicates the areas of minimal tidal effect.

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

The reference to mud shoals resulting from an earthquake brings to mind the possibility of liquefaction. This is perhaps what happened to the two submerged ancient cities close to modern Alexandria. Their remains lie nine metres under the surface of the Mediterranean.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Some supporters of a Black Sea Atlantis have suggested the shallow Strait of Kerch between Crimea and Russia as the location of Plato’s ‘shoals’(e) .

The tidal map above offers two areas west of Athens and Egypt that do appear to be credible location regions, namely, (1) from the Balearic Islands, south to North Africa and (2), a more credible straddling the Strait of Sicily. This region offers additional features, making it much more compatible with Plato’s account.

By contrast, just over a hundred miles south of that Strait, lies the Gulf of Gabés, which boasts the greatest tidal range (max 8 ft) within the Mediterranean.

The Gulf of Gabes formerly known as Syrtis Minor and the larger Gulf of Sidra to the east, previously known as Syrtis Major, was greatly feared by ancient mariners and continue to be very dangerous today because of the shifting sandbanks created by tides in the area.

There are two principal ancient texts that possibly support the gulfs of Syrtis as the location of Plato’s ‘shoal’. The first is from Apollonius of Rhodes who was a 3rd-century BC librarian at Alexandria. In his Argonautica (Bk IV ii 1228-1250)(a) he unequivocally speaks of the dangerous shoals in the Gulf of Syrtis. The second source is the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 27 13-18) written three centuries later, which describes how St. Paul on his way to Rome was blown off course and feared that they would run aground on “Syrtis sands.” However, good fortune was with them and after fourteen days they landed on Malta. The Maltese claim regarding St. Paul is rivalled by that of the Croatian island of Mljet as well Argostoli on the Greek island of Cephalonia. Even more radical is the convincing evidence offered by Kenneth Humphreys to demonstrate that the Pauline story is an invention(b).

Both the Strait of Sicily and the Gulf of Gabes have been included in a number of Atlantis theories. The Strait and the Gulf were seen as part of a larger landmass that included Sicily according to Butavand, Arecchi and Sarantitis who named the Gulf of Gabes as the location of the Pillars of Heracles. Many commentators such as Frau, Rapisarda and Lilliu have designated the Strait of Sicily as the ‘Pillars’, while in the centre of the Strait we have Malta with its own Atlantis claims.

Zhirov[458.25] tried to explain away the ‘shoals’ as just pumice stone, frequently found in large quantities after volcanic eruptions. However, Plato records an earthquake, not an eruption and Zhirov did not explain how the pumice stone was still a hazard many hundreds of years after the event. Although pumice can float for years, it will eventually sink(c). It was reported that pumice rafts associated with the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa were found floating up to 20 years after that event. Zhirov’s theory does not hold water (no pun intended) apart from which, Atlantis was destroyed as a result of an earthquake. not a volcanic eruption and I think that the shoals described by Plato were more likely to have been created by liquefaction and could not have endured for centuries.

Nevertheless, a lengthy 2020 paper(d) by Ulrich Johann offers additional information about pumice and in a surprising conclusion proposes that it was pumice rafts that inspired Plato’s reference to shoals!

Andrew Collins in an effort to justify his Cuban location for Atlantis needed to find Plato’s ‘shoals of mud’ in the Atlantic and for me, in what seems to have been an act of desperation he decided that the Sargasso Sea fitted the bill [072.42]. However Collins was not the first to make this suggestion. Chedomille Mijatovich (1842-1932), a Serbian politician, economist and historian was one of the first in modern times to suggest that the Sargasso Sea may have been the maritime hazard described by Plato as a ‘shoal of mud’, which resulted from the submergence of Atlantis. However, neither explains how anyone can mistake seaweed for mud!

The late Andis Kaulins believed that Atlantis did exist and considered two possible regions for its location; the Minoan island of Thera or some part of the North Sea that was submerged at the end of the last Ice Age when the sea levels rose dramatically. Kaulins noted that part of the North Sea is known locally as ‘Wattenmeer’ or Sea of Mud’ reminiscent of Plato’s description of the region where Atlantis was submerged, after that event.

An even more absurd suggestion came from the American scholar William Arthur Heidel (1868-1941), who denied the reality of Atlantis and wrote a critical paper [0374] on the subject (republished July 2013(g)). He claimed that an expeditionary naval force sent by Darius in 515 BC under Scylax of Caryanda to explore the Indus River, eventually encountered waters too shallow for his ships, and that this was the inspiration behind Plato’s tale of unnavigable seas. Heidel further claimed that Plato’s battle between Atlantis and Athens is a distorted account of the war of invasion between the Persians and the peoples of the Indus Valley (Now Pakistan)!

(a) https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/argo/argo53.htm

(b) https://www.jesusneverexisted.com/shipwreck.html

(c) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170523144110.htm

(e) Index (atlantis-today.com)

(f) https://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread61382/pg1

(g) A Suggestion concerning Plato’s Atlantis on JSTOR (archive.org)

(h) Atlantis – Wikipedia_?s=books&ie=UTF&qid=1376067567&sr=-