Doug Fisher

Expanding Earth Hypothesis *

The Expanding Earth Hypothesis.

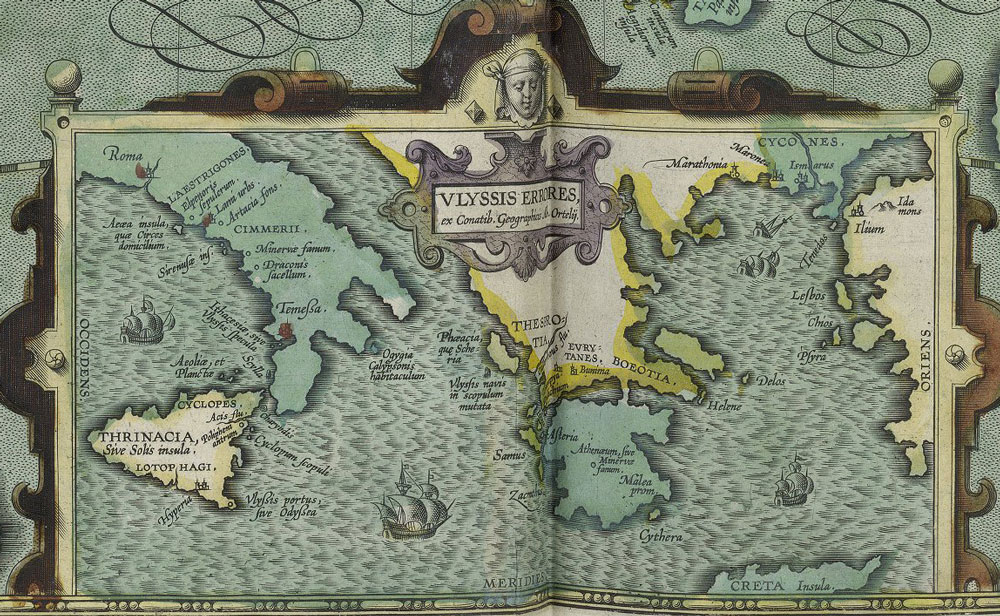

For thousands of years, it was accepted that the surface of the earth was in a static state. This belief persisted until the rediscovery of America in 1492 and the cartographic improvements during the following century before Abraham Ortelius in his 1596 Thesaurus Geographicus[1225] proposed that the Americas had once been joined to Europe and Africa. It is often claimed that in 1620 Francis Bacon commented on the close fit of eastern South America with the west coast of Africa, however, this, according to G.L. Herries Davies, is an exaggerated interpretation of what he actually said(o).

A number of others concurred with the jig-saw suggestion until 1858 when the French geographer Antonio Snider-Pellegrini offered[0555] a theory of crustal movement that was more fully developed in 1912 by Alfred Wegener, which he came to label ‘continental drift’(e). Snider-Pellegrini also thought that the Earth had been much smaller at the time of the biblical Genesis(ac)! The big objection to the theory was a lack of a convincing mechanism to explain it(f).

A number of writers have attempted to bring the theory of Continental Drift (CD) into the Atlantis debate. They seem to overlook the fact CD was proposed as a very very slow process, while Plato describes the demise of Atlantis as occurring in a single day and a night.

A number of writers have attempted to bring the theory of Continental Drift (CD) into the Atlantis debate. They seem to overlook the fact CD was proposed as a very very slow process, while Plato describes the demise of Atlantis as occurring in a single day and a night.

Wegener’s theory was debated until the late 1950’s when it morphed into the theory of Plate Tectonics (PT) following new developments in earth sciences in particular the recognition of seafloor spreading at mid-ocean ridges. However, PT as we know it demands subduction(z), which in itself has created new problems(aa)(ab).

The theory divides the lithosphere into a number of plates that are constantly moving in various directions at rates of a few centimetres a year. Competing with PT in the early years was the theory of Earth Crustal Displacement advocated by Charles Hapgood which claims that the entire crust of the earth moved as a unit. Endorsed by Albert Einstein it is fundamental to the theory of an Antarctic location for Atlantis proposed by Rose & Rand Flem-Ath.

Unfortunately, Plate Tectonics does not explain everything and ever since it gained the pre-eminence it currently enjoys, various writers have questioned what they perceive as its shortcomings(g)(h)(i).

A totally different proposal is that the earth is expanding. Although the concept did not get much attention until the 1980’s there are antecedents stretching back to 1888(a), when the earliest suggestion was made by the Russian, Ivan Yarkovsky (1844-1902). A year later the Italian geologist (and violinist) Roberto Montovani (1854-1933) proposed(I) a similar mechanism. In 1933, Ott Christoph

Hilgenberg(t) published Vom wachsenden Erdbal (The Expanding Earth) [1328].

In 1963, a Russian lady, Kamilla Abaturova, wrote to Egerton Sykes expressing the view that although her theory of an expanding Earth involved a ‘slow’ process, she proposed that at the time of Atlantis’ the radius of the Earth was 600 km shorter(af). In geological terms, this is far from ‘slow’!

The leading proponent of the theory today is arguably the, now retired, geologist Dr James Maxlow(b). A detailed outline of the theory is also offered on his website(c). For laymen like myself, a series of YouTube clips(d) are probably more informative. I have stated elsewhere that I am sympathetic towards the idea of earth expansion finding it somewhat more credible than plate tectonics. The truth of the matter is that since Ortelius first suggested that the continents of our planet had moved, all that has emerged since is a refinement of that basic idea leading to CD which became PT and as the latter still does not answer all the questions it raises, it is clear that further modification will be required. In December 2021, Maxlow published an overview of his current thinking on Expansion Tectonics(ag).

The Expanding Earth Hypothesis may, as its proponents claim, supply all those answers. Others do not think so, which brings me to J. Marvin Herndon who has ‘married’ the theory of an expanding earth with the idea of crustal plates(j) , naming his 2005 concept Whole-Earth Decompression Dynamics (WEDD).

The Thunderbolts.info website has a three-part article seeking to offer “an alternative to plate and extension tectonics”. The anonymous author suggests that an electrical element is involved in the development of our planet. An extensive look at mountain building is also included(y).

A 1998 paper(ah). by Bill Mundy an American Professor of Physics is still relevant. In it, he discusses the pros and cons of both plate tectonics and the expanding earth hypothesis and concluded that “Despite the success that standard plate-tectonics theory has enjoyed, there are phenomena that it currently is not able to model. Perhaps the most adequate model would incorporate Owens’ suggestion that there is both subduction and expansion. This would allow the earth to expand at a modest rate with reasonable changes in surface gravitation and also require some subduction for which the evidence seems convincing. But such a model presents the difficulty of finding suitable mechanisms for expansion, plate motion and subduction!”

In October 2022 Doug Fisher published a paper on Graham Hancock’s website highlighting weaknesses in the generally accepted theory of plate tectonics and seeking a review of the expanding earth hypothesis(ai).

Keith Wilson, an American researcher, has also developed a website(k) devoted to the EEH and linked it to Pole Shift. However, he goes further and introduces Mayan prophecies into the subject, which in my view is unwise in the light of recent events or rather non-events!

In the meanwhile, a number of Atlantis researchers have endorsed the EEH including, Stan Deyo, Georg Lohle and Rosario Vieni. Nicolai Zhirov referred to the growing support both in Russia and elsewhere for the EEH citing a number of its supporters, adding that “the idea of the Earth expanding (within reasonable limits) cannot be ruled out altogether as absurd.”[458.126]

A number of websites have dismissed the EEH as pseudoscience, which is confirmed by satellite measurements(m)(n).

There is also a variation of the standard expansion theory which proposes(q) that expansion may have occurred in fits and starts. There also seems to be evidence that the Earth is not alone with Venus expanding(r) and Mercury contracting(s).

Another matter that may be related to the claim of an expanding Earth is the question of the size of dinosaurs and other creatures and plants millions of years ago, which is claimed to have been impossible if gravity then was the same as today. A book[1218] by Stephen Hurrell has expanded on this idea. There is an interesting website(p) that deals with the enormous size of the dinosaurs as well as other creatures at the same period and the support it may offer the EEH.

Neal Adams, a respected graphic artist(u), is a vocal supporter of the EEH(v), but, he has gone further and has also proposed a growing Moon as well(w). Not content with that, he has extended his expansion investigations to other bodies in our Solar System, such as, Mars, Ganymede & Europa(x). Adams considers the term “Expanding Earth” a misnomer and has named his proposed expansion process ‘pair production’.(ad)

A December 2018 paper by Degezelle Marvin offers some new support for the EEH(ae). The author includes an interesting comparison of the problems of the currently accepted paradigm of plate tectonics with possible solutions offered by EEH. The author concludes with;

“The problems with plate tectonics were presented in this paper. Earth scientists dogmatically follow the plate tectonics theory that is falsified by geological data while Earth expansion is clearly a viable candidate to replace plate tectonics. Analysis map of the age of the oceanic lithosphere showed that the isochrons only ft on a smaller Earth with a calculated radius. Mountain formation has even been presented as a logical result of the Earth’s expansion. The average rate of the growth of the Earth’s radius is 1.22cm/year, obtained by geological methods.”

Finally, I cannot help thinking about those Victorians who thought that they had reached the pinnacle of scientific understanding. They were wrong and, I believe, that so are we, although we are slowly, very slowly, edging towards the truth, which may or may not involve the vindication of the Expanding Earth Hypothesis.

(a) https://www.checktheevidence.co.uk/cms/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=394&Itemid=59

(b) https://www.expansiontectonics.com/page2.html

(c) https://www.expansiontectonics.com/page3.html

(d) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OUkEu6YYR3s

(e) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continental_drift

(f) https://www.scientus.org/Wegener-Continental-Drift.html

(g) https://davidpratt.info/ncgt-jse.htm

(h) https://davidpratt.info/lowman.htm

(i) https://www.newgeology.us/presentation21.html

(j) https://web.archive.org/web/20200926204322/http://nuclearplanet.com/

(l) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberto_Mantovani

(n) https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/history-of-geology/2014/05/12/the-expanding-earth/

(o) Francis Bacon and Continental Drift (archive.org) *

(p) The Inflating Earth: 4 – Gravity | MalagaBay (archive.org)

(q) https://web.archive.org/web/20161203151134/http://www.xearththeory.com/expansion/

(r) https://web.archive.org/web/20200808000231/https://www.xearththeory.com/expanding-venus/

(s) https://web.archive.org/web/20200807234839/https://www.xearththeory.com/mercury/

(u) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neal_Adams

(v) https://www.naturalphilosophy.org/site/dehilster/2014/09/22/is-the-earth-expanding-and-even-growing/

(w) Neal Adams: 02 – The Growing Moon | MalagaBay (archive.org)

(x) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zy3_sWF7tv4

(y) https://www.thunderbolts.info/forum/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?f=4&t=16534 (link broken Oct. 2019) See: https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-3326/

(z) https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-subduction-3892831

(aa) https://www.newgeology.us/presentation8.html

(ac) https://www.annalsofgeophysics.eu/index.php/annals/article/view/4622

(ad) https://malagabay.wordpress.com/2015/12/17/neal-adams-01-the-growing-earth/

(ae) https://www.gsjournal.net/Science-Journals/Research%20Papers-Astrophysics/Download/7531

(af) Atlantis, Volume 16, No. 1, February 1963.

(ag) NCGTJV9N4_Pub.pdf (registeredsite.com)

(ah) https://www.grisda.org/assets/public/publications/origins/15053.pdf

(ai) Maps, Myths & Paradigms – Graham Hancock Official Website

Kircher, Athanasius

Fr. Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and a professor of ethics and mathematics at the University of Würzburg. In his day he was considered one of the greatest authorities in Europe on Chinese and Egyptian cultures, archaeology, ancient languages and astronomy. However, he was not without his detractors, one of whom was Descartes who robustly attacked Kircher’s scientific abilities. Kircher’s writings filled 44 folio volumes.

Fr. Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and a professor of ethics and mathematics at the University of Würzburg. In his day he was considered one of the greatest authorities in Europe on Chinese and Egyptian cultures, archaeology, ancient languages and astronomy. However, he was not without his detractors, one of whom was Descartes who robustly attacked Kircher’s scientific abilities. Kircher’s writings filled 44 folio volumes.

Kircher claimed to have deciphered the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, but this was later shown to be unfounded and drew highly critical comments such as that of the Egyptologist Sir E. A. Wallis Budge who wrote in 1910: Many writers pretended to have found the key to the hieroglyphics, and many more professed, with a shameless impudence which is hard to understand in these days, to translate the contents of the texts into a modern tongue. Foremost among such pretenders must be mentioned Athanasius Kircher, who, in the 17th century, declared that he had found the key to the hieroglyphic inscriptions; the translations which he prints in his Oedipus Aegyptiacus are utter nonsense, but as they were put forth in a learned tongue many people at the time believed they were correct. A more recent critique is available online(b).

When it is realised that more than a century was to pass after Kircher’s death before the Rosetta Stone was discovered and the work of Champollion finally gave us a reliable decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics, it is quite reasonable to treat Kircher’s translation as purely speculative. His efforts in this regard were recently described as ‘illusory’.

In recent times Kircher has regained widespread fame because of the map, published in his Mundus  Subterraneus [1203], which among a range of subjects(c), outlines Atlantis (Insula Atlantis) between Africa and America. This Latin text can now be read or downloaded online(a). A 1678 edition of the book held in the Fagel Collection in Trinity College, Dublin has been described as one of the most beautiful books in the collection(h).

Subterraneus [1203], which among a range of subjects(c), outlines Atlantis (Insula Atlantis) between Africa and America. This Latin text can now be read or downloaded online(a). A 1678 edition of the book held in the Fagel Collection in Trinity College, Dublin has been described as one of the most beautiful books in the collection(h).

In Mundus Subterraneus Kircher was the first to propose that the Canaries and the Azores were the mountain peaks of sunken Atlantis. His famous map has the north shown at the bottom with Africa and Spain on the left and America on the right. There is no particular significance in this fact as the convention of having North at the top of maps is relatively recent and generally attributed to the controversial 8th-century Irish cleric, Virgil of Salzburg, who was eventually appointed bishop of that city and later canonised as St. Virgilius. A Latin label on the map reads: “site of Atlantis, now beneath the sea, according to the beliefs of the Egyptians and the description of Plato. A chart based on beliefs and descriptions clearly shows that his offering is speculative and not a real map, although some claim that it is an ‘authentic’ depiction of Atlantis, such as can be seen on an hour-long YouTube video from a 1997 conference(g).

Despite being based on speculation, Kircher’s map is still widely used today. An article by Phil Edwards has commented on its continued use – ” We can only guess why one map became the iconic depiction of Atlantis, but there are a few reasonable assumptions. It had a veneer of scientific legitimacy, thanks to Kircher’s reputation and other work. It came at a time when the world was actively being reimagined. And Kircher’s map was one of the earliest ones nestled into an otherwise accurate depiction of the world. And perhaps most important is that once Atlantis’s appearance was established it couldn’t really be disproven. So the same map stuck around for centuries” (l).

Recently, Doug Fisher>>and Johan Nygren(m) have<<drawn attention to the similarities between a 1592 map of South America by Abraham Ortelius and Kircher’s Atlantis map when inverted(e). Frank Jacobs has highlighted the same comparison but also notes how the map might be seen as an image of Greenland(i). Some further background information on Kircher’s map is to be found online(f).

Kircher’s Atlantis map is widely used, particularly by supporters of an Atlantic Atlantis. Some, such as Dieter Thom, have followed Kircher’s view that Atlantis had been located in the Azores, while others have been more liberal in their interpretation of the map. Dale Huffman, Johan Nygren and Mario Dantas have associated the map with Greenland. Ian A. Fox has pushed matters further by nominating Baffin Bay west of Greenland as formerly the Plain of Atlantis. Now, while all these have kept their chosen Atlantis locations within the Atlantic Ocean conforming, at least to some extent, with Kircher’s map. However, there are a number of commentators who have employed the map to justify even more exotic locations. At one end of the world, Rand and Rose Flem-Ath were apparently inspired by Kircher’s map and opted for an Antarctic Atlantis, while at the other end, just south of the Arctic Circle Marco Francesco Bulloni has nominated the Solovetsky archipelago in northwest Russia as the home of Atlantis, once again inspired by Kircher. Of course, I’ve saved the best for last with Australia as the nominee and a specific location of Port Arthur in Tasmania(k).

Less known is his 1665 world map recently published on the atlan.org. website(j).

In 2004 a book[425] with the enticing title of Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything was published. It was edited by Paula Findlen and includes essays by leading historians of our day.

(a) https://archive.org/details/mundussubterrane02kirc

(b) https://publicdomainreview.org/2013/05/16/athanasius-kircher-and-the-hieroglyphic-sphinx/

(c) https://publicdomainreview.org/2012/11/01/athanasius-underground/

(e) https://atlantismaps.com/chapter_7.html (Link broken Nov. 2018) New replacement site is now being developed – https://www.copheetheory.com/

(f) https://www.vox.com/2015/4/30/8516829/imaginary-island-atlantis-map-kircher

(g) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZcuJKilUdw

(h) The Fagel Collection (archive.org)

(i) Could South America be Atlantis? – Big Think

(j) The World Map of Athanasius Kircher 1665. – Atlan.org

(k) The location of Atlantis, page 1 (archive.org) (The map was not saved by Wayback Machine)

(l) https://www.vox.com/2015/4/30/8516829/imaginary-island-atlantis-map-kircher

Fisher, Doug

Doug Fisher is the author of a long-awaited book with the intended title of The Atlantis Maps: The Rise of Atlantis and the Fall of a Paradigm in which he identifies Atlantis as North and South America with the Plain described by Plato being the region of Mesopotamia, in northeast Argentina. The book was eventually published in 2018 as Maps, Myths and Paradigms [1924] with details of its contents listed on his website.(c) Four chapters had been available online(a) together with a few additional articles.

Doug Fisher is the author of a long-awaited book with the intended title of The Atlantis Maps: The Rise of Atlantis and the Fall of a Paradigm in which he identifies Atlantis as North and South America with the Plain described by Plato being the region of Mesopotamia, in northeast Argentina. The book was eventually published in 2018 as Maps, Myths and Paradigms [1924] with details of its contents listed on his website.(c) Four chapters had been available online(a) together with a few additional articles.

Fisher has published an illustrated paper on Graham Hancock’s website with the self-explanatory title of The Walls of Atlantis(b). His suggestion of a huge outer wall encircling the city of Atlantis has been disputed by Jim Allen, provoking further comments(c) from Fisher.

He has also criticised the methodology, which Allen used to place Atlantis on the Altiplano(d), while I question the credibility of both their theories.

When Fisher’s book was finished and due for publication with its new title, he closed his old website and prepared a new site(e) to coincide with the publication of the book.

Fisher has published two other papers(f) on Hancock’s website relating to the maps of Johannes Schöner and Oronteus Finaeus.>In October 2022 he published another paper on the same site challenging the currently accepted theory of plate tectonics highlighting weaknesses in the concept and proposing a fresh look at the expanding earth hypothesis.<

(a) See: Archive 2865 (no images)

(b) https://grahamhancock.com/fisherd3/

(c) http://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread646457/pg2 (halfway down the page)

(d) http://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread821281/pg1

(e) http://www.copheetheory.com/

(f) https://grahamhancock.com/author/doug-fisher/

(g) Maps, Myths & Paradigms – Graham Hancock Official Website *

Finaeus, Oronteus

Oronteus Finaeus (1494-1555) was a celebrated cartographer who produced a map in 1531 which is claimed by some that, like the Piri Reis  Map, it depicts the coast of an ice-free Antarctica. Charles Hapgood rediscovered it in 1959(a) in the Library of Congress. This idea is then used to support the concept of the existence of a very early civilisation that was capable of sophisticated map-making. It is then just a short step to name this civilisation ‘Atlantis’. Some, such as the Flem-Aths went further and actually nominated Antarctica as the home of Atlantis.

Map, it depicts the coast of an ice-free Antarctica. Charles Hapgood rediscovered it in 1959(a) in the Library of Congress. This idea is then used to support the concept of the existence of a very early civilisation that was capable of sophisticated map-making. It is then just a short step to name this civilisation ‘Atlantis’. Some, such as the Flem-Aths went further and actually nominated Antarctica as the home of Atlantis.

Robert Argod has used the Oronteus Finaeus Map to support his contention that the Polynesians had originated in Antarctica.

>Christine Pellech has an article published on the Atlantisforschung website taken from her 2013 book Die Entdeckung von Amerika [1188] (The Discovery of America), in which she reviews the range of medieval maps displaying geographical details ‘unknown’ until centuries later!(e) Her reference to the Mark McMenamin coins can be ignored as they have since been shown to be forgeries (See: Sardinia).<

However, a contrary view has been expressed by Paul Heinrich who commenting on Graham Hancock’s assertion that the map shows an ice-free Antarctica, points out that in the case of West Antarctica, the underlying bedrock is, in the main, hundreds of feet below sea level and would not show on a real map of the region(c).

A more recent website(b), although not endorsing an Antarctic Atlantis, discusses some of these old maps in very great detail and on Graham Hancock’s website. The site is based on a number of chapters from a work-in-progress, The Atlantis Maps: The Rise of Atlantis and the Fall of a Paradigm by Doug Fisher. He identifies the Plain of Mesopotamia in Northern Argentina as the location of Atlantis.

(a) https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/198001/piri.reis.and.the.hapgood.hypotheses.htm

(b) https://web.archive.org/web/20180831132132/https://www.atlantismaps.com/ ^30.10.2020 “This URL has been excluded from the Wayback Machine.”

(c) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-3967/

Argentina

Argentina is one of the latest locations to be proposed for Atlantis. Doug Fisher has a work-in-progress entitled The Atlantis Maps: The Rise of Atlantis and the Fall of a Paradigm. On his website(a) Fisher offers four chapters from his forthcoming book. The first three chapters on offer discuss in great detail the 16th century maps that are claimed to show an ice-free Antarctica. In the final chapter he argues that Plato’s text could only have been referring to the Americas as the location of Atlantis. He goes further and specifies the Plain of Mesopotamia in northern Argentina as the plain described by Plato with a landform in the Paraná Delta conforming to the dimensions he gave for the circular city of Atlantis.

Argentina is one of the latest locations to be proposed for Atlantis. Doug Fisher has a work-in-progress entitled The Atlantis Maps: The Rise of Atlantis and the Fall of a Paradigm. On his website(a) Fisher offers four chapters from his forthcoming book. The first three chapters on offer discuss in great detail the 16th century maps that are claimed to show an ice-free Antarctica. In the final chapter he argues that Plato’s text could only have been referring to the Americas as the location of Atlantis. He goes further and specifies the Plain of Mesopotamia in northern Argentina as the plain described by Plato with a landform in the Paraná Delta conforming to the dimensions he gave for the circular city of Atlantis.

Completely unrelated to Atlantis but perhaps even more intriguing is a circular feature in the  Paraná Delta know as ‘El Ojo’ (The Eye) which has only recently been discovered. It is a perfectly circular ‘lake’ 120 metres across with a floating ‘island’ in it which is also perfectly circular. There is an English language video(b) clip outlining the extent of the mystery and the plans to mount a multidisciplinary expedition to study it further.

Paraná Delta know as ‘El Ojo’ (The Eye) which has only recently been discovered. It is a perfectly circular ‘lake’ 120 metres across with a floating ‘island’ in it which is also perfectly circular. There is an English language video(b) clip outlining the extent of the mystery and the plans to mount a multidisciplinary expedition to study it further.

>(a) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20180831132132/https://www.atlantismaps.com/ ^30.10.2020 “This URL has been excluded from the Wayback Machine.”<

Plain of Atlantis

The Plain of Atlantis is one of the principal features recorded by Plato in great detail. He describes it being “3000 stades in length and at its midpoint 2000 stades in breath from the coast” (Critias 118a, trans. Lee). The shape of the plain is frequently given as ‘rectangular’ or ‘oblong’ and contained an efficient irrigation system that was fed by mountain streams. The fertility of the plain gave the inhabitants two crops annually.

The dimensions given by Plato would translate into 370 x 555 km (230 x 345 miles). However, the late Ulf Richter has recently proposed(a) that the dimensions originally given to Solon by the priests of Sais used the Egyptian ‘khet’ (52.4 meters) as the unit of measurement. Possibly Solon recorded the figures without mentioning the units employed. In Ireland, we changed over to the metric system some years ago, but builders still speak and write of using ‘2×4’ lengths of timber without specifying that they are referring to inches. Such unqualified notations made at present could be interpreted in the future as 2×4 centimetres. This illustrates how reasonable Richter’s suggestion is. The acceptance of it would give us a more credible 105 x 157 km (65 x 97 miles) as the dimensions of this plain. Richter also maintains that the plain was in fact a river delta, which explains the remarkable fertility of the land.

Rich McQuillen has adopted Richter’s suggestion that there was some unspecified translation confusion regarding the use of the Egyptian ‘khet’ or the Greek ‘stade’ by Solon. The revised dimensions led McQuillen to propose territory adjacent to Canopus at the mouth of the Nile as the location of the Plain of Atlantis. Canopus along with nearby Pharos and Herakleoin were destroyed by liquefaction resulting from an earthquake. McQuillen’s ideas also coincide with Richter’s additional proposal that Atlantis was situated on a river delta(a).

Paul Dunbavin offered a number of possible explanations of how the obvious exaggeration of Plato’s numbers occurred(f). He suggests that “Regardless of how the original story came to be recorded by the priests of Sais, they too must have translated the dimensions from a native (Atlantian) source. The chain of preservation goes something like this:

- Recorded in unknown local units of measure

- Transmitted by traders or colonists to archaic Egypt

- Recorded by the Saite priests when the temple was built

- Transcribed numerous times up to the era of Solon

- converted to Greek units by/for Solon

- Interpreted by Plato for his narratives

- Translated for modern readers by Greek scholars

Errors could have been introduced at any of these intermediate stages in the preservation of the history. Therefore other than to conclude that the measurements are sensibly too large by a huge multiple then it becomes fruitless to seek a submerged rectangular plain of any precise scale; be it in the Atlantic or Mediterranean.”

However, I am not convinced that the problem with Plato’s numbers is a matter of misunderstanding the units of measurement used. As I pointed out in Joining the Dots [p89] “The numbers attributed to the Atlantean military appear to be just as extravagant as Plato’s other figures for time, distance, and area. Now, where months can be substituted for years and khets for stades, soldiers are units in any language and so Plato’s excessive manpower figures cannot be explained away by claiming there had been some confusion over the unit of measurement employed.”

My conclusion is that we should be looking at the possible manner in which an alien numerical notation system was misunderstood somewhere along that chain of transmission listed above by Dunbavin. For those that claim that Plato concocted the entire Atlantis story, it should be obvious that if he had, he would have offered more credible data, but, apparently in deference to Solon, repeated the numbers recorded by him.

Galanopoulos and Bacon commenting [263.36] on the plain described in Critias 118a-e concluded that Plato had been referring to a second plain, “Next, the plain surrounding the city does not appear to be the same as the one close to the Ancient Metropolis since this lay in the centre of the island at a distance of 50 stades (6 miles) from the sea. Whereas the plain surrounding the City was 3,000 stades (340 miles) and 2,000 stades (227 miles) wide; and so the centre of this plain must have been very much more than six miles from the sea. The attempt to reconcile these statements by suggesting that the Ancient Metropolis was not in the centre of the island but close to the sea in the middle of one of the sides of the island likewise will not work in view of the passage (Critias 113d) which states that the belts of water encircling the metropolis were everywhere equidistant from the centre of the island.”

Jim Allen, who supports an Andean location for Atlantis, offers a strong argument against other principal Atlantis candidates by critically examining the plains included in alternative location theories(c). However, it must be pointed out that Allen had to divide Plato’s dimensions for the plain by two in order to shoehorn it into his chosen location.

While I accept that there is evidence that there was flooding on the Altiplano, it took place some thousands of years before the Bronze Age Atlantis described by Plato and certainly long before he wrote “this is why the sea in that area is to this day impassible to navigation, which is hindered by mud just below the surface, the remains of the sunken island.” (Timaeus 25d – Desmond Lee) This is not a description that can be applied to anywhere on the Altiplano during the 1st millennium BC. Apart from that, Plato’s account clearly states that Atlantis was submerged and was still so in his own day, making Allen’s critique somewhat redundant.

An interesting suggestion, although badly flawed, was made by Jean Deruelle who proposed ‘Doggerland‘ in the North Sea as the location of Atlantis, adding an interesting twist to Plato’s description of the Plain. “Deruelle, an engineer and a geologist by profession, offers a hypothesis that is rational, highly precise, and based on his areas of expertise. No other hypothesis than Deruelle’s tackles so credibly the most outlandish elements in Plato’s description of Atlantis: the description of a vast plain, surrounded by a man-made ditch, 180 meters broad and thirty meters deep, large enough to circulate supertankers: it was not a ditch, but a dyke, build over centuries to protect a large part of Doggerland against the slowly rising waters of the North Sea.”(d)

Diaz-Montexano maintains that Plato never said that the plain was shaped like a rectangle.

The Mediterranean, between Sicily and North Africa, has been offered by a number of commentators, such as Alberto Arecchi and Alex Hausmann, as the location of the Plain of Atlantis. There is evidence of large areas of land having been submerged within the region between Malta and the Pelagie Islands. I include here a passing reference from Ernle Bradford who sailed the region which may be of interest to supporters of a Central Mediterranean Atlantis. When discussing the Egadi Islands off the west coast of Sicily he describes Levanzo, the smallest of the group as being “once joined to Sicily, and the island was surrounded by a large fertile plain. Levanzo, in fact, was joined to more than Sicily. Between this western corner of the Sicilian coast and the Cape Bon peninsula in Tunisia there once lay rich and fertile valleys-perhaps, who knows, long lost Atlantis?” [1011.57]

The number of different locations that have been proposed for the plain is obviously a reflection of the number of sites suggested for the city of Atlantis. I list the most popular below with the added comment that, at best, only one can be correct while all may be wrong.

Plain of Atlantis

Mauritania (David Edward)

Mesara Plain on Crete (Braymer)

Central Plain of Ireland (Erlingsson)

Sea of Azov (Flying Eagle & Whispering Wind)

Altiplano of Bolivia (Jim Allen)

Andalusian Plain (Diaz-Montexano)

North Sea (Doggerland) (Jean Deruelle)

Plain of Catania, Sicily

Plain of Campidano, Sardinia (Giuseppe Mura)

Souss-Massa Plain, Morocco (Michael Hübner) (Mario Vivarez)

Greenland (Mario Dantas)

Beni, Bolivia (David Antelo)

Mesopotamia in Argentina (Doug Fisher)

Black Sea (Werner E. Friedrich) (George K. Weller)

Plain of Troy (J.D.Brady)

South of England (E.J. deMeester)

Carthage (Pallatino & Corbato)

Celtic Shelf (Dan Crisp)

Western Plain, Cuba (Andrew Collins)

Portugal (Peter Daughtrey)

Off the coast of Wales (Paul Dunbavin)

Florida (Dennis Brooks)

Atlantic Floor (Michael Jaye)

Baffin Bay, Greenland (Ian Fox)

Between Sicily and Malta (Axel Hausmann)

Pannonian Plain, Hungary+(Ticleanu, Constantin & Nicolescu)

Guadalete River Plain (Karl Jürgen Hepke)

Mouth of the Nile (Rich McQuillen) (Robert Graves)

South China Sea Indonesia (Dhani Irwanto) (Bill Lauritzen)

Saudi Arabia (Stan Deyo)

Venezuelan Basin (Caribbean) Brad Yoon (P.P. Flambas)

Yucatan Peninsula (Mark Carlotto)(b)

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20160326200714/https://www.atlantis-schoppe.de/richter.pdf

(b) A Commentary on Plato’s “Myth” of Atlantis – Before Atlantis

(c) https://web.archive.org/web/20200707234820/http://www.atlantisbolivia.org/plaincomparison.htm

(d) https://www.q-mag.org/the-great-plain-of-atlantis-was-it-in-doggerland.html

(f) file:///C:/Users/Tony/Downloads/An_Atlantis_Miscellany.pdf *

Ortelius, Abraham

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) was a Flemish cartographer who produced the first modern atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum[1226], which at the time was reputed to have been the most expensive book ever printed.

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) was a Flemish cartographer who produced the first modern atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum[1226], which at the time was reputed to have been the most expensive book ever printed.

It is interesting that he included the mythical island of Hi-Brasil (Brasil) off the coast of Ireland as well as the equally mysterious Frisland (Frieslant). Both can be clearly seen on his map using the link below(a).

In 1596 Ortelius was struck by the possibility that America, Europe and Africa had at one time been joined together but had over time become separated, an idea expressed in his Thesaurus Geographicus[1225]. Ortelius also included a speculative southern landmass, Terra Australis, which he designated as a “land of parrots”.

In 1597, Ortelius was the first to map(d) the travels of Homer’s Odysseus, notably locating all his adventures in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean, which was probably just a reflection of the limits of Greek maritime knowledge at the time that the narrative originated!

Ortelius suggested that Atlantis had been located in North America but that they had separated in the very distant past! Before modern theories of Continental Drift and its successor, Plate Tectonics, the idea of landbridges between continents was popular as an explanation for the spread of animals and people around the world. Some suggested as an alternative, the existence of lost continents such as Atlantis in the Atlantic, which acted as a stepping-stone between the continents(c).

Four hundred years later Alfred Wegener incorporated some of Ortelius’ ideas into his theory of Continental Drift, which later led to the current theory of Plate Tectonics.

A purpose-built polar exploration ship, m.v. Ortelius, was named after the geographer.

Recently, Doug Fisher has drawn attention to the similarities between a 1592 map of South America by Ortelius and the well-known Kircher map of Atlantis(b).

(a) https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e2/OrteliusWorldMap1570.jpg

(b) https://atlantismaps.com/chapter_7.html (link broken Oct. 2018) New website in development. (https://www.copheetheory.com/)

(c) Wayback Machine (archive.org) *

(d) https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/geography-odyssey

Island, Peninsula or Continent?

Island, Peninsula or Continent? Advocates of a continental rather than island identification for Atlantis have to contend with the fact that Plato never referred to Atlantis as a continent instead he used the Greek words for ‘island’, namely ‘nesos’ and ‘neson’. Their line of argument is that these words in addition to ‘island’ or ‘islands’ can also mean “islands of an archipelago” or “peninsula”. Furthermore, it is claimed that the ancient Greeks had no precise word for ‘peninsula’.

Gilles le Noan[912], quoted by Papamarinopoulos[629.558], has offered evidence that there was no differentiation in Greek between ‘island’ and ‘peninsula’ until the time of Herodotus in the 5th century BC. In conversation with Mark Adams[1070.198] he explains that in the sixth century BC, when Solon lived, nesos had five geographic meanings. “One, an island as we know it. Two, a promontory. Three, a peninsula. Four,

Elena P. Mitropetrou a Greek archaeologist at the University of Patras, delivered two papers to the 2008 Atlantis Conference in Athens [750]. She also pointed out that in the 6th century BC, the Greek word nesos was employed to describe an island, but also, a peninsula or a promontory. Mitropetrou herself considers the Iberian peninsula to be the ‘island of Atlantis.’

Robert Bittlestone, in his Odysseus Unbound [1402.143] also notes that “nesos usually means an island whereas cheronesos means a peninsula, but Homer could not have used cheronesos when referring to the peninsula of Argostoli for two very good reasons. First, it cannot be fitted into the metre of the epic verse and second, the word hadn’t yet been invented: it doesn’t occur in Greek literature until the 5th century BC.”

Another researcher, Roger Coghill, echoed the views of many when he wrote on an old webpage that “To the Greeks peninsulae were the same as islands, so the Peloponnesian peninsula was “the island of Pelops” and the Chersonnese was to them “the island of Cherson”. Similarly in describing a place found after escaping the Pillars of Hercules, Plato quite normally describes the Lusitanian coast (modern Portugal) as an “island”, reached, he clearly says, after passing Cadiz”.

Johann Saltzman claimed that ‘nesos’ did not mean ‘island’ or ‘peninsula’ but ‘land close to water’. However, I would be happier sticking to the respected Liddell & Scott’s interpretation of island or peninsula. If Saltzman is correct, what word did the Greeks use for island?

The Modern Greek word for peninsula is ‘chersonesos’ which is derived from ‘khersos’ (dry) and ‘nesos’ (island) and can be seen as a reasonable description of a peninsula. It is worth noting that the etymology of the English word ‘peninsula’ is from the Latin ’paene’ (almost) and ’insula’ (an island).

Jonas Bergman maintains that the Greek concept of ‘island’ is one of detachment or isolation. He also points out that the original Egyptian word for ‘island’ can also mean lowland or coastland because the Egyptians had a different conception of ’island’ to either the ancient Greeks or us. Some commentators have claimed that the Egyptians of Solon’s time described any foreign land as an island.

Eberhard Zangger offers another correction of the Atlantis mystery: If one compares the land-sea distribution in Egypt and in the Aegean Sea, it becomes obvious why the Egyptians used at that time the expression “from the islands”. While today the word “island” has a clear meaning, this was not the case in the late Bronze Age. For the Egyptians more or less all strangers came from the islands. As there had been practically no islands in Egypt, the ancient Egyptian language did not have any special character for it. The hieroglyphic used for “island” was also meaning “sandy beach” or “coast” and was generally used for “foreign countries” or “regions on the other side of the Nile”.

A contributor to the Skeptic’s Dictionary(b) has added “I remind you that the Greek definition of “island” paralleled that of “continent.” To the Greeks, Europe was a continent. West Africa was an island, especially since it was cut off from the rest of what we now call “Africa” by a river that ran south from the Atlas mountains and then west to what is now the western Sahara. This now dry river was explored by Byron Khun de Prorok in the 1920s.”

Reginald Fessenden wrote: “One Greek term must be mentioned because it has given rise to much confusion. The word ‘Nesos’ is still translated as meaning ‘island’ but it does not mean this at all, except perhaps in late Greek. The Peloponnesus is a peninsula. Arabia was called a “nesos” and so was Mesopotamia”. This ambiguity in the written Greek and Egyptian of that period was highlighted at the 2005 Atlantis Conference by Stavros Papamarinopoulos.

Werner Wickboldt pointed out at the same conference that Adolph Schulten in the 1920’s referred to a number of classical writers who used the term ‘nesos’ in connection with the Nile, Tiber, Indus and Tartessos, all of which possessed deltas with extensive networks of islands.

To confuse matters even further, there have been a number of theories based on the idea that the ‘island’ of Atlantis was in fact land surrounded by rivers rather than the sea. These include Mesopotamia in Argentina proposed by Doug Fisher, the Island of Meroë in Sudan suggested by Thérêse Ghembaza and a large piece of land bound by the Mississippi, Ohio, and Potomac rivers offered by Henriette Mertz. However, none of these locations matches Plato’s description of Atlantis as a maritime trading nation with a naval fleet of 1200 ships, nor do any of them explain how they controlled the Mediterranean as far as Egypt and Tyrrhenia.

>Another Atlantis-island variant is based on the existence of a large inland sea where the Sahara now exists. Gerald Wells has proposed that the Atlas Mountains in what is now Algeria were effectively an island isolated by this inland sea to the south, the Mediterranean to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. He claims that the City of Atlantis was situated on the Hill of Garet-el-Djeter.

Related to Wells’ theory is the highly technical approach of Michael Hübner who located Atlantis on the Souss Massa Plain of Morocco, where today the plain and its adjacent valleys are called ‘island’ by the native Amazigh people.(Constraint 2.2.1.2 R102)[632].<

The waters around Plato’s island are indeed muddy!