Robert Lorentz Scranton

Greece

Greece as the home of Atlantis was unknown until the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries when the Minoan Hypothesis began to evolve and is still one of the more popular theories today. Other locations in the Aegean have been proposed by researchers such as Paulino Zamarro and C. A. Djonis as well as three Italian linguists, Facchetti, Negri and Notti, who presented a paper(a) to the 2005 Atlantis Conference outlining their reasons for supporting an Aegean backdrop to the Atlantis story.

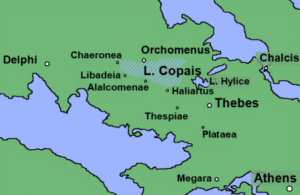

Mainland Greece has also been proposed as home to Atlantis. In the middle of the 20th century R. L. Scranton suggested Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, an idea later modified by Oliver D. Smith, who subsequently completely abandoned the idea of Atlantis as a reality. More recently, it has been proposed that Atlantis was just an allegory of Athens and that its port, ancient Piraeus, was partly the inspiration behind Plato’s description of Atlantis(b). On the other hand, the Dutch linguist, Joannes Richter, also views the Plato’s story as fiction and suggested that “probably Plato used the model of the draining and irrigation system at Lake Copais as a model for the ancient metropolis at the ‘island Atlantis’ in an imaginary war between Athens and Atlantis.”(c)

The sunken Greek cities of Pavlopetri and Helike have also prompted suggestions of a connection with Plato’s lost island.

(a) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/document-250811/

(b) Archive 2887 | (atlantipedia.ie) (see last paragraphs)

(c) https://www.academia.edu/41219454/The_War_against_Atlantis?sm=a (link broken) *

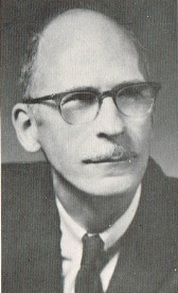

Scranton, Robert Lorentz

Robert Lorentz Scranton (1912-1993) was an American professor of Classical Art at the University of Chicago. He was the author of Greek Walls[1223] in which he endeavoured to develop a stylistic classification system of walls that might assist chronological sequencing.

the author of Greek Walls[1223] in which he endeavoured to develop a stylistic classification system of walls that might assist chronological sequencing.

He wrote a short article(c) with the daring title of “Lost Atlantis  Found Again?” in which he suggests the possibility that Atlantis had been located in Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, Greece. The area is rich in ancient remains including that of a number of canals. However, Scranton was somewhat unsettled by the fact that Plato had described Atlantis as being in the Central Mediterranean, to the west of both Athens and Egypt (see Crit.114c & Tim.25a/b).

Found Again?” in which he suggests the possibility that Atlantis had been located in Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, Greece. The area is rich in ancient remains including that of a number of canals. However, Scranton was somewhat unsettled by the fact that Plato had described Atlantis as being in the Central Mediterranean, to the west of both Athens and Egypt (see Crit.114c & Tim.25a/b).

Scranton’s 1949 article was subsequently made available on Oliver D. Smith’s website(a). Scranton’s Atlantis theory had elements in common with that of Smith’s,>who abandoned his Atlantis theory some years ago in favour of a sceptical view of Plato’s narrative.

Joannes Richter, the Dutch linguist, has published a paper, The War against Atlantis, in which he also looks at the idea that Lake Copaïs may have inspired elements of the Atlantis story.<

In recent years, excavations in the Lake Copaïs region have revealed more extensive ancient remains than anticipated(b).

An annual Robert L. Scranton Lectureship was established in 1999.

(a) https://atlantisresearch.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/lost-atlantis-found.pdf (now offline – see entry for Oliver D. Smith) See: (c) below

(b) https://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2016/article/rediscovering-a-giant1

(c) Archaeology 2, 1949, p159-162 https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40078396