Oliver D.Smith

Arcadia

Arcadia is a central region of the Peloponnese in Greece. It is one of a number of locations that have been proposed as inspiring elements of Plato’s Atlantis story. One proponent is Oliver D. Smith who argues that “Plato based his king Atlas on a mythical Arcadian king of the same name and his main inspiration for Atlantis was the town Methydrium and nearby city Megalopolis, both in Arcadia.”

story. One proponent is Oliver D. Smith who argues that “Plato based his king Atlas on a mythical Arcadian king of the same name and his main inspiration for Atlantis was the town Methydrium and nearby city Megalopolis, both in Arcadia.”

This, together with some other details, such as similarities between the ten kings of Atlantis and the ten kings of Arcadia led Smith to his conclusion(a).

Greece

Greece as the home of Atlantis was unknown until the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries when the Minoan Hypothesis began to evolve and is still one of the more popular theories today. Other locations in the Aegean have been proposed by researchers such as Paulino Zamarro and C. A. Djonis as well as three Italian linguists, Facchetti, Negri and Notti, who presented a paper(a) to the 2005 Atlantis Conference outlining their reasons for supporting an Aegean backdrop to the Atlantis story.

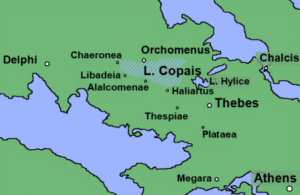

Mainland Greece has also been proposed as home to Atlantis. In the middle of the 20th century R. L. Scranton suggested Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, an idea later modified by Oliver D. Smith, who subsequently completely abandoned the idea of Atlantis as a reality. More recently, it has been proposed that Atlantis was just an allegory of Athens and that its port, ancient Piraeus, was partly the inspiration behind Plato’s description of Atlantis(b). On the other hand, the Dutch linguist, Joannes Richter, also views the Plato’s story as fiction and suggested that “probably Plato used the model of the draining and irrigation system at Lake Copais as a model for the ancient metropolis at the ‘island Atlantis’ in an imaginary war between Athens and Atlantis.”(c)

The sunken Greek cities of Pavlopetri and Helike have also prompted suggestions of a connection with Plato’s lost island.

(a) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/document-250811/

(b) Archive 2887 | (atlantipedia.ie) (see last paragraphs)

(c) https://www.academia.edu/41219454/The_War_against_Atlantis?sm=a (link broken) *

Smith, Oliver D.

Oliver D. Smith studied Classics at Roehampton University and is currently studying archaeology at the Oxford Learning College. In May 2013, he published his BA disserta tion, entitled Atlantis as Sesklo, as an ebook(i).

tion, entitled Atlantis as Sesklo, as an ebook(i).

Smith devoted the initial part of his paper to a review of the interpretation of the Atlantis story by euhemerists since the time of Plato. Having briefly, and I might say dismissively, dealt with some modern theories, and then began to unveil a new hypothesis. Firstly, he proceeded to ignore archaeological opinion and support the early date for the existence of Atlantis. He also argued that Atlantis was destroyed by the flood that occurred during the reign of the Pelasgian king Ogyges.

Smith daringly suggested that the inspiration for the Atlantean capital was Sesklo, an ancient site situated north of Athens near modern Volos.

Although Smith has obviously researched his subject, I cannot agree with his conclusion, which I consider somewhat speculative. Apart from taking issue with the early date for Atlantis, Plato described the Atlantean attack as coming from the west, not the north. Furthermore, Sesklo is certainly not submerged and the site is too small to match Plato’s description of the city.

He also contended that the claim by Plato that Atlantis was ‘greater than Libya and Asia combined’ was in fact a reference to the extreme age of Atlantis!(c)

On March 14th, 2014, Smith announced(b) that “I have now closed my blog, and removed my research to work on a new project which will take many years (I will be working on a proper book covering the literary genre and origin of Atlantis). Personally, I think the Atlantis community has too many location hypotheses and not enough material put out exploring Plato’s dialogues, etc, and Atlantis in general in detail.” He expanded on this in a later article.(f)

Nevertheless, Smith did return to the Atlantis question in May 2016 and declared his belief that Plato’s account was complete fiction!(d) Readers may be interested in reading other blogs by Smith as they touch on other matters that relate to Atlantis studies such as the Pillars of Heracles(j) and the etymology of ‘Atlantis’. Smith identifies four locations in southern Iberia that have been designated as locations of the ‘Pillars’. He names them as Mastia, Mainake, Strait of Gibraltar, and Cádiz.

In 2020 he published a paper attacking the Minoan Hypothesis and continuing his assault on what he claims is Plato’s fictional account of Atlantis.(g)

Perhaps more relevant to an assessment of Smith’s reliability is a review of his, meandering, tortured intellectual journey to date(e).

In January 2022, Smith, who is unhappy with Hisarlik as the location of Troy and dissatisfied with alternatives proposed by others has now proposed a Bronze Age site, Yenibademli Höyük, on the Aegean island of Imbros(h). His paper was published in the Athens Journal of History (AJH).

>In early 2023, Smith published a paper on the Researchgate website, in which he sought to identify the inspiration behind what he prefers to describe as Plato’s fictional Atlantis. This he now believes to have been the ancient Arcadian kingdom of Atlantos centred on the town of Methydrium, which is situated near modernday Methydrio(k).<

(c) The Size of Atlantis: A New Interpretation (link broken)

(d) Archive 3062 | (atlantipedia.ie)

(e) Oliver D. Smith – Encyclopedia Dramatica (archive.org) (link broken) See: Archive 3195

(f) http://shimajournal.org/issues/v10n2/d.-Smith-Shima-v10n2.pdf

(g) (6) (PDF) Atlantis and the Minoans | Oliver D Smith – Academia.edu

(h) https://athensjournals.gr/history/2022-8-1-4-Smith.pdf

(i) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-3062/

(j) https://www.academia.edu/39947152/In_Search_of_the_Pillars_of_Heracles

(k) (PDF) Arcadian Atlantis and Plato’s Pseudomythology (researchgate.net) *

Pindar

Pindar (522-443 BC) was one of the nine ancient Greek lyric poets. He refers to the ‘Pillars of Heracles’ in three of his victory odes, Olympian 3.43-45, Nemean 3.19-23 and Isthmian 4.11-13, doing so in a manner which indicates that the term was used as a metaphor for the limit of human (Greek) experience. As such, the location of the Pillars would have changed as the colonial and commercial expansion of the Greeks developed beyond the Aegean.

>One commentator has interpreted Pindar’s Olympian Ode 3 as referring to the Pillars of Herakles being placed at the ‘Springs of Ister’ on the Danube near Belgrade, noting that “this is the very edge of Pindar’s Celtic world and a point beyond which a Greek probably did not want to venture.“(b)<

Oliver D.Smith has drawn attention to the Nemean Ode 4, 65-70 as having echoes of Plato’s description in it(a).

(a) https://atlantisresearch.wordpress.com/ (now offline)

Troy

Troy is believed to have been founded by Ilus, son of Troas, giving it the names of both Troy and Ilios (Ilium) with some minor variants.

“According to new evidence obtained from excavations, archaeologists say that the ancient city of Troy in northwestern Turkey may have been more than six centuries older than previously thought. Rüstem Aslan, who is from the Archaeology Department of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (ÇOMU), said that because of fires, earthquakes, and wars, the ancient city of Troy had been destroyed and re-established numerous times throughout the years.” This report pushes the origins of this famous city back to around 3500 BC(s).

Dating Homer’s Troy has produced many problems. Immanuel Velikovsky has drawn attention to some of these difficulties(aa). Ralph S. Pacini endorsed Velikovsky’s conclusion that the matter could only be resolved through a revised chronology. Pacini noted that “the proposed correction of Egyptian chronology produces a veritable flood of synchronisms in the ancient middle east, affirming many of the statements by ancient authors which had been discarded by historians as anachronisms.”(z)

The precise date of the ending of the Trojan War continues to generate comment. A 2012 paper by Rodger C. Young and Andrew E. Steinmann has offered evidence that the conclusion of the conflict occurred in 1208 BC, which agrees with the date recorded on the Parian Marble(ah). This obviously conflicts with the date calculated by Eratosthenes of 1183 BC. A 2009 paper(ai) by Nikos Kokkinos delves into the methodology used by Eratosthenes to arrive at this date. Peter James has listed classical sources that offered competing dates ranging from 1346 BC-1127 BC, although Eratosthenes’ date had more general acceptance by later commentators [46.327] and still has support today.

New dating for the end of the Trojan War has been presented by Stavros Papamarinopoulos et al in a paper(aj) now available on the Academia.edu website. Working with astronomical data relating to eclipses in the 2nd millennium BC, they have calculated the ending of the War to have taken place in 1218 BC and Odysseus’ return in 1207 BC.

The city is generally accepted by modern scholars to have been situated at Hissarlik in what is now northwest Turkey. Confusion over identifying the site as Troy can be traced back to the 1st century AD geographer Strabo, who claimed that Ilion and Troy were two different cities!(t) In the 18th century, many scholars consider the village of Pinarbasi, 10 km south of Hissarlik, as a more likely location for Troy.

The Hisarlik “theory had first been put forward in 1821 by Charles Maclaren, a Scottish newspaper publisher and amateur geologist. Maclaren identified Hisarlik as the Homeric Troy without having visited the region. His theory was based to an extent on observations by the Cambridge professor of mineralogy Edward Daniel Clarke and his assistant John Martin Cripps. In 1801, those gentlemen were the first to have linked the archaeological site at Hisarlik with historic Troy.”(m)

The earliest excavations at Hissarlik began in 1856 by a British naval officer, John Burton. His work was continued in 1863 until 1865 by an amateur researcher, Frank Calvert. It was Calvert who directed Schliemann to Hissarlik and the rest is history(j).

However, some high-profile authorities, such as Sir Moses Finley (1912-1986), have denounced the whole idea of a Trojan War as fiction in his book, The World of Odysseus [1139]. Predating Finley, in 1909, Albert Gruhn argued against Hissarlik as Troy’s location(i).

Not only do details such as the location of Troy or the date of the Trojan War continue to be matters for debate, but surprisingly, whether the immediate cause of the Trojan War, Helen of Troy was ever in Troy or not, is another source of controversy. A paper(ab) by Guy Smoot discusses some of the difficulties. “Odysseus’, Nestor’s and Menelaos’ failures to mention that they saw or found Helen at Troy, combined with the fact that the only two witnesses of her presence are highly untrustworthy and problematic, warrant the conclusion that the Homeric Odyssey casts serious doubts on the version attested in the Homeric Iliad whereby the daughter of Zeus was detained in Troy.”

The Swedish scholar, Martin P. Nilsson (1874-1967) who argued for a Scandinavian origin for the Mycenaeans [1140], also considered the identification of Hissarlik with Homer’s Troy as unproven.

A less dramatic relocation of Troy has been proposed by John Chaple who placed it inland from Hissarlik. This “theory suggests that Hisarlik was part of the first defences of a Trojan homeland that stretched far further inland than is fully appreciated now and probably included the entire valley of the Scamander and its plains (with their distinctive ‘Celtic’ field patterns). That doesn’t mean to say that most of the battles did not take place on the Plain of Troy near Hisarlik as tradition has it but this was only the Trojans ‘front garden’ as it were, yet the main Trojan territory was behind the defensive line of hills and was vastly bigger with the modern town of Ezine its capital – the real Troy.” (af)

Troy as Atlantis is not a commonly held idea, although Strabo, suggested such a link. So it was quite understandable that when Swiss geo-archaeologist, Eberhard Zangger, expressed this view [483] it caused quite a stir. In essence, Zangger proposed(g) that Plato’s story of Atlantis  was a retelling of the Trojan War.

was a retelling of the Trojan War.

For me, the Trojan Atlantis theory makes little sense as Troy was to the northeast of Athens and Plato clearly states that the Atlantean invasion came from the west. In fact, what Plato said was that the invasion came from the ‘Atlantic Sea’ (pelagos). Although there is some disagreement about the location of this Atlantic Sea, all candidates proposed so far are west of both Athens and Egypt.(Tim.24e & Crit. 114c)

Troy would have been well known to Plato, so why did he not simply name them? Furthermore, Plato tells us that the Atlanteans had control of the Mediterranean as far as Libya and Tyrrhenia, which is not a claim that can be made for the Trojans. What about the elephants, the two crops a year or in this scenario, where were the Pillars of Heracles?

A very unusual theory explaining the fall of Troy as a consequence of a plasma discharge is offered by Peter Mungo Jupp on The Thunderbolts Project website(d) together with a video(e).

Zangger proceeded to re-interpret Plato’s text to accommodate a location in North-West Turkey. He contends that the original Atlantis story contains many words that have been critically mistranslated. The Bronze Age Atlantis of Plato matches the Bronze Age Troy. He points out that Plato’s reference to Atlantis as an island is misleading, since, at that time in Egypt where the story originated, they frequently referred to any foreign land as an island. He also compares the position of the bull in the culture of Ancient Anatolia with that of Plato’s Atlantis. He also identifies the plain mentioned in the Atlantis narrative, which is more distant from the sea now, due to silting. Zangger considers these Atlantean/Trojans to have been one of the Sea Peoples who he believes were the Greek-speaking city-states of the Aegean.

Rather strangely, Zangger admits (p.220) that “Troy does not match the description of Atlantis in terms of date, location, size and island character…..”, so the reader can be forgiven for wondering why he wrote his book in the first place. Elsewhere(f), another interesting comment from Zangger was that “One thing is clear, however: the site of Hisarlik has more similarities with Atlantis than with Troy.”

There was considerable academic opposition to Zangger’s theory(a). Arn Strohmeyer wrote a refutation of the idea of a Trojan Atlantis in a German-language book [559].

An American researcher, J. D. Brady, in a somewhat complicated theory, places Atlantis in the Bay of Troy.

In January 2022, Oliver D. Smith who is unhappy with Hisarlik as the location of Troy and dissatisfied with alternatives offered by others, proposed a Bronze Age site, Yenibademli Höyük, on the Aegean island of Imbros(v). His paper was published in the Athens Journal of History (AJH).

To confuse matters further Prof. Arysio Nunes dos Santos, a leading proponent of Atlantis in the South China Sea places Troy in that same region of Asia(b).

Furthermore, the late Philip Coppens reviewed(h) the question marks that still hang over our traditional view of Troy.

Felice Vinci has placed Troy in the Baltic and his views have been endorsed by the American researcher Stuart L. Harris in a number of articles on the excellent Migration and Diffusion website(c). Harris specifically identifies Finland as the location of Troy, which he claims fell in 1283 BC although he subsequently revised this to 1190 BC, which is more in line with conventional thinking. The dating of the Trojan War has spawned its own collection of controversies.

However, the idea of a northern source for Homeric material is not new. In 1918, an English translation of a paper by Carus Sterne (Dr Ernst Ludwig Krause)(1839-1903) was published under the title of The Northern Origin of the Story of Troy(n). Iman Wilkens is arguably the best-known proponent of a North Atlantic Troy, which he places in Britain. Another scholar, who argues strongly for Homer’s geography being identifiable in the Atlantic, is Gerard Janssen of the University of Leiden, who has published a number of papers on the subject(u). Robert John Langdon has endorsed the idea of a northern European location for Troy citing Wilkens and Felice Vinci (w). However, John Esse Larsen is convinced that Homer’s Troy had been situated where the town Bergen on the German island of Rügen(x) is today.

Most recently (May 2019) historian Bernard Jones(q) has joined the ranks of those advocating a Northern European location for Troy in his book, The Discovery of Troy and Its Lost History [1638]. He has also written an article supporting his ideas in the Ancient Origins website(o). For some balance, I suggest that you also read Jason Colavito’s comments(p).

Steven Sora in an article(k) in Atlantis Rising Magazine suggested a site near Lisbon called ‘Troia’ as just possibly the original Troy, as part of his theory that Homer’s epics were based on events that took place in the Atlantic. Two years later, in the same publication, Sora investigated the claim for an Italian Odyssey(l). In the Introduction to The Triumph of the Sea Gods [395], he offers a number of incompatibilities in Homer’s account of the Trojan War with a Mediterranean backdrop.

Roberto Salinas Price (1938-2012) was a Mexican Homeric scholar who caused quite a stir in 1985 in Yugoslavia, as it was then when he claimed that the village of Gabela 15 miles from the Adriatic’s Dalmatian coast in what is now Bosnia-Herzegovina, was the ‘real’ location of Troy in his Homeric Whispers [1544].

More recently another Adriatic location theory has come from the Croatian historian, Vedran Sinožic in his book Naša Troja (Our Troy) [1543]. “After many years of research and exhaustive work on collecting all available information and knowledge, Sinožic provides numerous arguments that prove that the legendary Homer Troy is not located in Hisarlik in Turkey, but is located in the Republic of Croatia – today’s town of Motovun in Istria.” Sinožic who has been developing his theory over the past 30 years has also identified a connection between his Troy and the Celtic world.

Similarly, Zlatko Mandzuka has placed the travels of Odysseus in the Adriatic in his 2014 book, Demystifying the Odyssey[1396].

Fernando Fernández Díaz is a Spanish writer, who has moved Troy to Iberia in his Cómo encontramos la verdadera Troya (y su Cultura material) en Iberia [1810] (How we find the real Troy (and its material Culture) in Iberia.).

Like most high-profile ancient sites, Troy has developed its own mystique, inviting the more imaginative among us to speculate on its associations, including a possible link with Atlantis. Recently, a British genealogist, Anthony Adolph, has proposed that the ancestry of the British can be traced back to Troy in his book Brutus of Troy[1505]. Petros Koutoupis has written a short review of Adolph’s book(ad).

Caleb Howells, a content writer for the Greek Reporter website, among others, has written The Trojan Kings of Britain [2076] due for release in 2024. In it he contends that the legend of Brutus is based on historical facts. However, Adolph came to the conclusion that the story of Brutus is just a myth(ae), whereas Howells supports the opposite viewpoint.

Iman Wilkens delivered a lecture(y) in 1992 titled ‘The Trojan Kings of England’.

It is thought that Schliemann has some doubts about the size of the Troy that he unearthed, as it seemed to fall short of the powerful and prestigious city described by Homer. His misgivings were justified when many decades later the German archaeologist, Manfred Korfmann (1942-2005), resumed excavations at Hissarlik and eventually exposed a Troy that was perhaps ten times greater in extent than Schliemann’s Troy(r).

An anonymous website with the title of The Real City of Troy(ag) began in 2020 and offers regular blogs on the subject of Troy, the most recent (as of Dec. 2023) was published in Nov. 2023. The author is concerned with what appear to be other cities on the Plain of Troy unusually close to Hissarlik!

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20150912081113/https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/1995/95.02.18.html

(b) http://www.atlan.org/articles/atlantis/

(c) http://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?authorid=113

(d) https://www.thunderbolts.info/wp/2013/09/16/troy-homers-plasma-holocaust/

(e) Troy – Homers Plasma holocaust – Episode 1 – the iliad (Destructions 17) (archive.org) *

(f) https://www.moneymuseum.com/pdf/yesterday/03_Antiquity/Atlantis%20en.pdf

(g) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mo-lb2AAGfY

(h) https://www.philipcoppens.com/troy.html or See: Archive 2482

(i) https://www.jstor.org/stable/496830?seq=14#page_scan_tab_contents

(j) https://turkisharchaeonews.net/site/troy

(k) Atlantis Rising Magazine #64 July/Aug 2007 See: Archive 3275

(l) Atlantis Rising Magazine #74 March/April 2009 See: Archive 3276

(m) https://luwianstudies.org/the-investigation-of-troy/

(n) The Open Court magazine. Vol.XXXII (No.8) August 1918. No. 747 See: https://archive.org/stream/opencourt_aug1918caru/opencourt_aug1918caru_djvu.txt

(o) https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/location-troy-0011933

(q) https://www.trojanhistory.com/

(r) Manfred Korfmann, 63, Is Dead; Expanded Excavation at Troy – The New York Times (archive.org)

(t) https://web.archive.org/web/20121130173504/http://www.6millionandcounting.com/articles/article5.php

(u) https://leidenuniv.academia.edu/GerardJanssen

(x) http://odisse.me.uk/troy-the-town-bergen-on-the-island-rugen-2.html

(y) https://phdamste.tripod.com/trojan.html

(z) http://www.mikamar.biz/rainbow11/mikamar/articles/troy.htm (Link broken)

(aa) Troy (varchive.org)

(ab) https://chs.harvard.edu/guy-smoot-did-the-helen-of-the-homeric-odyssey-ever-go-to-troy/

(ac) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-europe/aeneas-troy-0019186

(ad) https://diggingupthepast.substack.com/p/rediscovering-brutus-of-troy-the#details

(ae) https://anthonyadolph.co.uk/brutus-of-troy/

(af) http://www.johnchaple.co.uk/troy.html

(aj) http://www.academia.edu/7806255/A_NEW_ASTRONOMICAL_DATING_OF_THE_TROJAN_WARS_END *

Pelasgians

Pelasgians or Pelasgi is the term applied to early populations of the Aegean, prior to the Flood of Deucalion and the subsequent arrival of the Hellenic peoples to the region. Pelasgian Greeks are recognised as having occupied Crete at the end of the 2nd millennium BC. It is unclear from classical sources(b) exactly what regions the Pelasgians occupied, not to mention when or where they originated.

Some writers such as Densusianu have postulated a Pelasgian Empire extending over a large stretch of central Europe.

Euripides stated that the Pelasgians were later called Danaans.

Spiro N. Konda believes that today’s Albanians are descendants of the Pelasgians and has written The Albanians and the Pelasgian Problem in support of this idea, unfortunately, it is in Albanian, but some of his arguments can be read, in English, online(a).

Oliver D. Smith in his book Atlantis in Greece identified “the Pelasgians with both the Atlanteans and prehistoric Athenians – as two regional tribes at war with each other”.

A more radical, highly speculative and quite incredible, alternative definition is offered by Marin, Minella and Schievenin[0972.471], which is that Pelasgians were refugees from their homeland in Antarctica after its catastrophic destruction. They claim that these refugees were also known as Titans, Tyrrhenians and Atlanteans, among other names! They also propose that the Pelasgians arrived in Egypt in 10,500 BCE “led by Osiris/Menes, and joined the local people, who were indigenous Negroid such as the image engraved in the Sphinx.” They further claim that anthropology calls them Cro-Magnon!

James Bailey noted in The God-Kings & the Titans [149.158] that the Pelasgians were equated with the Peoples of the Sea in the Cambridge Ancient History(c).

>Lars Karlsson is Professor in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History at Uppsala University and in a 2023 paper(e) he offered the theory “that the Pelasgians were ‘proto-Etruscans’, since the Pelasgian island of Lemnos has inscriptions in Etruscan.”

The degree of confusion surrounding the identity of the Pelasgians is clearly demonstrated in the Wikipedia article on the subject(d).<

(a) https://at001.wordpress.com/2011/04/09/the-etymology-of-the-names-of-pelasgian-gods-2/

(b) https://stoa.wordpress.com/2008/08/05/the-pelasgians-in-the-ancient-historians-texts/

(c) https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.283059/page/n33/mode/2up (2nd. Edition, Vol. II, p.8)

(d) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelasgians *

(e) https://isvroma.org/en/2023/01/13/research-seminar-the-early-history-of-the-etruscans-2/ *

Minoan Hypothesis

The Minoan Hypothesis proposes an Eastern Mediterranean origin for Plato’s Atlantis centred on the island of Thera and/or Crete. The term ‘Minoan’ was coined by the renowned archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the mythic King Minos. (Sir Arthur was the son of another well-known British archaeologist, Sir John Evans). Evans thought that the Minoans had originated in Northern Egypt and came to Crete as refugees. However, recent genetic studies seem to indicate a European ancestry!

It is claimed(a) that Minoan influence extended as far as the Iberian Peninsula as early as 3000 BC and is reflected thereby what is now known as the Los Millares Culture. Minoan artefacts have also been found in the North Sea, but it is not certain if they were brought there by Minoans themselves or by middlemen. The German ethnologist, Hans Peter Duerr, has a paper on these discoveries on the Academia.edu website(e). He claims that the Minoans reached the British Isles as well as the Frisian Islands where he found artefacts with some Linear A inscriptions near the site of the old German trading town of Rungholt, destroyed by a flood in 1362(f).

The advanced shipbuilding techniques of the Minoans are claimed to have been unmatched for around 3,500 years until the 1950s (l).

The Hypothesis had its origin in 1872 when Louis Guillaume Figuier was the first to suggest [0296] a link between the Theran explosion and Plato’s Atlantis. The 1883 devastating eruption of Krakatoa inspired Auguste Nicaise, in an 1885 lecture(c) in Paris, to cite the destruction of Thera as an example of a civilisation being destroyed by a natural catastrophe, but without reference to Atlantis.

The Minoan Hypothesis proposes that the 2nd millennium BC eruption(s) of Thera brought about the destruction of Atlantis. K.T. Frost and James Baikie, in 1909 and 1910 respectively, outlined a case for identifying the Minoans with the Atlanteans, decades before the extent of the massive 2nd millennium BC Theran eruption was fully appreciated by modern science. In 1917, Edwin Balch added further support to the Hypothesis [151].

As early as April 1909, media speculation was already linking the discoveries on Crete with Atlantis(h), despite Jowett’s highly sceptical opinion.

Supporters of a Minoan Atlantis suggest that when Plato wrote of Atlantis being greater than Libya and Asia he had mistranscribed meison (between) as meizon (greater), which arguably would make sense from an Egyptian perspective as Crete is between Libya and Asia, although it is more difficult to apply this interpretation to Thera which is further north and would be more correctly described as being between Athens and Asia. Thorwald C. Franke has now offered a more rational explanation for this disputed phrase when he pointed out [0750.173] that “for Egyptians, the world of their ‘traditional’ enemies was divided in two: To the west, there were the Libyans, to the east there were the Asians. If an Egyptian scribe wanted to say, that an enemy was more dangerous than the ‘usual’ enemies, which was the case with the Sea Peoples’ invasion, then he would have most probably said, that this enemy was “more powerful than Libya and Asia put together”.

It has been ‘received wisdom’ that the Minoans were a peace-loving people, however, Dr Barry Molloy of Sheffield University has now shown that the exact opposite was true(d) and that “building on recent developments in the study of warfare in prehistoric societies, Molloy’s research reveals that war was, in fact, a defining characteristic of the Minoan society, and that warrior identity was one of the dominant expressions of male identity.”

In 1939, Spyridon Marinatos published, in Antiquity, his opinion that the eruption of Thera had led to the demise of the Minoan civilisation. However, the editors forbade him to make any reference to Atlantis. In 1951, Wilhelm Brandenstein published a Minoan Atlantis theory, echoing many of Frost’s and Marinatos’ ideas, but giving little credit to either.

However, Colin MacDonald, an archaeologist at the British School in Athens, believes that “Thira’s eruption did not directly affect Knossos. No volcanic-induced earthquake or tsunami struck the palace which, in any case, is 100 meters above sea level.” The Sept. 2019 report in Haaretz suggests it’s very possible the Minoans were taken over by another civilization and may have been attacked by the Mycenaeans, the first people to speak the Greek language and they flourished between 1650 B.C. and 1200 B.C. Archaeologists believe that the Minoan and Mycenaean civilisations gradually merged, with the Mycenaeans becoming dominant, leading to the shift in the language and writing system used in ancient Crete.

The greatest proponents of the Minoan Hypothesis were arguably A.G. Galanopoulos and Edward Bacon. Others, such as J.V. Luce and James Mavor were impressed by their arguments and even Jacques Cousteau, who unsuccessfully explored the seas around Santorini, while Richard Mooney, the ‘ancient aliens’ writer, thought [0842] that the Minoan theory offered a credible solution to the Atlantis mystery. More recently Elias Stergakos has proposed in an overpriced 68-page book [1035], that Atlantis was an alliance of Aegean islands that included the Minoans.

Moses Finley, the respected classical scholar, wrote a number of critical reviews of books published by prominent supporters of the Minoan Hypothesis, namely Luce(aa), Mavor(y)(z) as well as Galanopoulos & Bacon(aa)(ab). Some responded on the same forum, The New York Review of Books.

Andrew Collins is also opposed to the Minoan Hypothesis, principally because “we also know today that while the Thera eruption devastated the Aegean and caused tsunami waves that destroyed cities as far south as the eastern Mediterranean, it did not wipe out the Minoan civilization of Crete. This continued to exist for several generations after the catastrophe and was succeeded by the later Mycenaean peoples of mainland Greece. For these reasons alone, Plato’s Atlantic island could not be Crete, Thera, or any other place in the Aegean. Nor can it be found on the Turkish mainland at the time of Thera’s eruption as suggested by at least two authors (James and Zangger) in recent years(ad).“

Alain Moreau has expressed strong opposition to the Minoan Hypothesis in a rather caustic article(i), probably because it conflicts with his support for an Atlantic location for Atlantis. In more measured tones, Ronnie Watt has also dismissed a Minoan Atlantis, concluding that “Plato’s Atlantis happened to become like the Minoan civilisation on Theros rather than to be the Minoan civilisation on Theros.” In 2001, Frank Joseph wrote a dismissive critique of the Minoan Hypothesis referring to Thera as an “insignificant Greek island”.(x)

Further opposition to the Minoan Hypothesis came from R. Cedric Leonard, who has listed 18 objections(q) to the identification of the Minoans with Atlantis, keeping in mind that Leonard is an advocate of the Atlantic location for Plato’s Island.

Atlantisforschung has highlighted Spanuth’s opposition to the Minoan Hypothesis in a discussion paper on its website. I have published here a translation of a short excerpt from Die Atlanter that shows his disdain for the idea of an Aegean Atlantis.

“Neither Thera nor Crete lay in the ‘Atlantic Sea’, but in the Aegean Sea, which is expressly mentioned in Crit. 111a and contrasted with the Atlantic Sea. Neither of the islands lay at the mouth of great rivers, nor did they “sink into the sea and disappear from sight.” ( Tim. 25d) The Aegean Sea never became “impassable and unsearchable because of the very shallow mud”. Neither Solon nor Plato could have said of the Aegean Sea that it was ‘still impassable and unsearchable’ or that ‘even today……….an impenetrable and muddy shoal’ ‘blocks the way to the opposite sea (Crit.108e). Both had often sailed the Aegean Sea and their contemporaries would have laughed at them for telling such follies.” (ac)

Lee R. Kerr is the author of Griffin Quest – Investigating Atlantis [0807], in which he sought support for the Minoan Hypothesis. Griffins (Griffons, Gryphons) were mythical beasts in a class of creatures that included sphinxes. Kerr produced two further equally unconvincing books [1104][1675], all based on his pre-supposed link between Griffins and Atlantis or as he puts it “whatever the Griffins mythological meaning, the Griffin also appears to tie Santorini to Crete, to Avaris, to Plato, and thus to Atlantis, more than any other single symbol.” All of which ignores the fact that Plato never referred to a Sphinx or a Griffin!

The hypothesis remains one of the most popular ideas with the general public, although it conflicts with many elements in Plato’s story. A few examples of these are, where were the Pillars of Heracles? How could Crete/Thera support an army of one million men? Where were the elephants? There is no evidence that Crete had walled cities such as Plato described. The Minoan ships were relatively light and did not require the huge harbours described in the Atlantis story. Plato describes the Atlanteans as invading from their western base (Tim.25b & Crit.114c); Crete/Santorini is not west of either Egypt or Athens

Gavin Menzies attempted to become the standard-bearer for the Minoan Hypothesis. In The Lost Empire of Atlantis [0780], he argues for a vast Minoan Empire that spread throughout the Mediterranean and even discovered America [p.245]. He goes further and claims that they were the exploiters of the vast Michigan copper reserves, which they floated down the Mississippi for processing before exporting it to feed the needs of the Mediterranean Bronze industry. He also accepts Hans Peter Duerr’s evidence that the Minoans visited Germany, regularly [p.207].

Tassos Kafantaris has also linked the Minoans with the exploitation of the Michigan copper, in his paper, Minoan Colonies in America?(k) He claims to expand on the work of Menzies, Mariolakos and Kontaratos. Another Greek Professor, Minas Tsikritsis, also supports the idea of ancient Greek contact with America. However, I think it is more likely that the Minoans obtained their copper from Cyprus, whose name, after all, comes from the Greek word for copper.

Oliver D. Smith has charted the rise and decline in support for the Minoan Hypothesis in a 2020 paper entitled Atlantis and the Minoans(u).

Frank Joseph has criticised [0802.144] the promotion of the Minoan Hypothesis by Greek archaeologists as an expression of nationalism rather than genuine scientific enquiry. This seems to ignore the fact that Figuier was French, Frost, Baikie and Bacon were British, Luce was Irish and Mavor was American. Furthermore, as a former leading American Nazi, I find it ironic that Joseph, a former American Nazi leader, is preaching about the shortcomings of nationalism.

While the suggestion of an American connection may seem far-fetched, it would seem mundane when compared with a serious attempt to link the Minoans with the Japanese, based on a study(o) of the possible language expressed by the Linear A script. Gretchen Leonhardt(r) also sought a solution in the East, offering a proto-Japanese origin for the script, a theory refuted by Yurii Mosenkis(s), who promotes Minoan Linear A as proto-Greek. Mosenkis has published several papers on the Academia.edu website relating to Linear A(t). However, writing was not the only cultural similarity claimed to link the Minoans and the Japanese offered by Leonhardt.

Furthermore, Crete has quite clearly not sunk beneath the waves. Henry Eichner commented, most tellingly, that if Plato’s Atlantis was a reference to Crete, why did he not just say so? After all, in regional terms, ‘it was just down the road’. The late Philip Coppens was also strongly opposed to the Minoan Hypothesis.(g)

Eberhard Zangger, who favours Troy as Atlantis, disagrees strongly [0484] with the idea that the Theran explosion was responsible for the 1500 BC collapse of the ‘New Palace’ civilisation.

Excavations on Thera have revealed very few bodies resulting from the 2nd millennium BC eruptions there. The understandable conclusion was that pre-eruption rumblings gave most of the inhabitants time to escape. Later, Therans founded a colony in Cyrene in North Africa, where you would expect that tales of the devastation would have been included in their folklore. However, Eumelos of Cyrene, originally a Theran, opted for the region of Malta as the remnants of Atlantis. How could he have been unaware of the famous history of his family’s homeland?

A 2008 documentary, Sinking Atlantis, looked at the demise of the Minoan civilisation(b). James Thomas has published an extensive study of the Bronze Age, with particular reference to the Sea Peoples and the Minoans(j).

In the 1990s, art historian and museum educator, Roger Dell, presented an illustrated lecture on the art and religion of the Minoans titled Art and Religion of the Minoans: Europe’s first civilization”, which offered a new dimension to our understanding of their culture(p). In this hour-long video, he also touches on the subject of Atlantis and the Minoans.

More extreme is the theory of L. M. Dumizulu, who offers an Afrocentric view of Atlantis. He claims that Thera was part of Atlantis and that the Minoans were black!(m)

In 2019, Nick Austin attempted [1661] to add further support to the idea of Atlantis on Crete, but, in my opinion, he failed. The following year, Sean Welsh also tried to revive the Minoan Hypothesis in his book Apocalypse [1874], placing the Atlantean capital on Santorini, which was destroyed when the island erupted around 1600 BC. He further claims that the ensuing tsunami led to the biblical story of the Deluge.

Evan Hadingham published a paper(v) in 2008 in which he discussed the possibility that the Minoan civilisation was wiped out by the tsunami generated by the eruption(s) of Thera. Then, seven years later he produced a second paper(w) exonerating the tsunami based on new evidence or lack of it.

In April 2023, an attempt was made to breathe some new life into the Minoan Hypothesis in an article(ae) on the Greek Reporter website. This unconvincing piece claims “Plato describes in detail the Temple of Poseidon on Atlantis, which appears to be identical to the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete.” The writer, Caleb Howells, has conveniently overlooked that Atlantis was submerged creating dangerous shoals and remained a maritime hazard even up to Plato’s day (Timaeus 25d). The Knossos Palace is on a hill and offers no evidence of ever having been submerged. Try again.

The same reporter did try again with another unconvincing piece supporting the Minoan Hypothesis, also on the Greek Reporter site, in October 2023(af). This time, he moved the focus of his claim to Santorini where he now placed the Palace of Poseidon relocating it from Crete! I suppose he will eventually make his mind up. Nevertheless, Howells revisited the subject of the Palace of Poseidon just a few weeks later, once again identifying it as the Palace of Knossos – “Plato’s account of the lost civilization of Atlantis includes a description of a marvelous temple of god Poseidon. It was said to have been in the center of Atlantis, so it was a very prominent part. However, in most investigations into the origin of Atlantis, this detailed temple description is ignored. In fact, an analysis of Plato’s details indicates that the Temple of Poseidon on Atlantis was actually identical to the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete, Greece.” (ag)

Most Atlantis theories manage to link their their chosen site with some of the descriptive details provided by Plato. The Minoan Hypothesis is no exception, so understandably Howells has highlighted the similarities, while ignoring disparities. The Minoans were primarily concerned with trading, not territorial expansion. When did they engage in a war with Athens or threaten Egypt? If Howells can answer that he may have something relevant to build upon!

>For a useful backdrop to the Minoan civilisation I suggest that readers have a look at a fully illustrated 2019 lecture by Dr. Gregory Mumford of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In it he give a broad overview of the Eastern Mediterranean, with a particular emphasis on the Aegean Sea, during the Middle- Late Bronze Age (2000-1200 BC). (ah) <

(a) http://www.minoanatlantis.com/Minoan_Spain.php

(b) http://video.pbs.org/video/1204753806/

(c) http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Les_Terres_disparues

(d) http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/article00826.html

(e) See: Archive 3928

(f) http://dienekes.blogspot.ie/2008/08/minoans-in-germany.html

(g) https://web.archive.org/web/20180128190713/http://philipcoppens.com/lectures.php (June 3, 2011)

(j) https://medium.com/the-bronze-age

(k) https://www.scribd.com/document/161156089/Minoan-Colonies-in-America

(m) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QqTQeF2gLpg

(o) Archive 3930 | (atlantipedia.ie)

(p) https://vimeo.com/205582944 Video

(q) https://web.archive.org/web/20170113234434/http://www.atlantisquest.com/Minoan.html

(r) https://konosos.net/2011/12/12/similarities-between-the-minoan-and-the-japanese-cultures/

(t) https://www.academia.edu/31443689/Researchers_of_Greek_Linear_A

(u) https://www.academia.edu/43892310/Atlantis_and_the_Minoans

(v) Did a Tsunami Wipe Out a Cradle of Western Civilization? | Discover Magazine

(w) https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/megatsunami-may-wiped-europes-first-great-civilization/

(x) Atlantis Rising magazine #27 http://pdfarchive.info/index.php?pages/At

(y) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(z) https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1969/12/04/back-to-atlantis-again/

(aa) Back to Atlantis | by M.I. Finley | The New York Review of Books (archive.org)

(ab) The End of Atlantis | by A.G. Galanopoulos | The New York Review of Books (archive.org)

(ac) Jürgen Spanuth über ‘Atlantis in der Ägäis’ – Atlantisforschung.de

(ad) Kreta oder Thera als Atlantis? – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(ae) Was Atlantis’ Temple of Poseidon the Palace of Knossos in Crete? (greekreporter.com)

(af) Was Atlantis a Minoan Civilization on Santorini Island? (greekreporter.com)

(ag) https://greekreporter.com/2023/12/01/atlantis-temple-poseidon-palace-knossos-crete/

Concentric Rings *

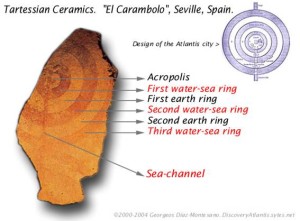

The Concentric Rings or other architectural features extracted by artists from Plato’s description of the capital of Atlantis have  continually fascinated students of the story and many have attempted to link them with similar ancient features found elsewhere in the world as evidence of a widespread culture. Stonehenge, Old Owstrey, Carthage and Syracuse have all been suggested, but such comparisons have never been convincing. Diaz-Montexano has recently published(a) an image of a fragment of pottery found near Seville in Spain that shows concentric circles and insists that it is a symbol of Atlantis. Ulf Erlingsson has made a similar claim regarding some concentric circles carved on a stone basin found at Newgrange in Ireland.

continually fascinated students of the story and many have attempted to link them with similar ancient features found elsewhere in the world as evidence of a widespread culture. Stonehenge, Old Owstrey, Carthage and Syracuse have all been suggested, but such comparisons have never been convincing. Diaz-Montexano has recently published(a) an image of a fragment of pottery found near Seville in Spain that shows concentric circles and insists that it is a symbol of Atlantis. Ulf Erlingsson has made a similar claim regarding some concentric circles carved on a stone basin found at Newgrange in Ireland.

Less well-known are the concentric stone circles that are to be found on the island of Lampedusa in the Strait of Sicily(b).

In 1969 two commercial pilots, Robert Brush and Trigg Adams photographed a series of large concentric circles in about three feet of water off the coast of Andros in the Bahamas. Estimates of the diameter of the circles range from 100 to 1,000 feet. Apparently, these rings are now covered by sand. It is hard to understand how such a feature in such very shallow water cannot be physically located and inspected. Richard Wingate in his book [0059] estimated the diameter at 1,000 yards. However, the rings described by Wingate were apparently on land, among Andros’ many swamps.

A recent (2023) report has drawn attention to the ancient rock art found on Kenya’s Mfangano Island where a number of concentric circles estimated as 4,000 years old can be seen(q).

Two papers presented to the 2005 Atlantis Conference on Melos describe how an asteroid impact could produce similar concentric rings, which, if located close to a coast, could be converted easily to a series of canals for seagoing vessels. The authors, Filippos Tsikalas, V.V. Shuvavlov and Stavros Papamarinopoulos gave examples of such multi-ringed concentric morphology resulting from asteroid impacts. Not only does their suggestion provide a rational explanation for the shape of the canals but would also explain the apparent over-engineering of those waterways.

At the same conference, the late Ulf Richter presented his idea [629.451], which included the suggestion that the concentric rings around the centre of the Atlantis capital had a natural origin. Richter has proposed that the Atlantis rings were the result of the erosion of an elevated salt dome that had exposed alternating rings of hard and soft rock that could be adapted to provide the waterways described by Plato.

Georgeos Diaz-Montexano has suggested that the ancient city under modern Jaen in Andalusia, Spain had a concentric layout similar to Plato’s description of Atlantis. In August 2016 archaeologists from the University of Tübingen revealed the discovery(i) of a Copper Age, Bell Beaker People site 50km east of Valencina near Seville, where the complex included a series of concentric earthwork circles.

A very impressive example of man-made concentric stone circles, known in Arabic as Rujm el-Hiri and in Hebrew as Gilgal Refaim(a), is to be found on the Golan Heights, now part of Israeli-occupied Syria. It consists of four concentric walls with an outer diameter of 160metres. It has been dated to 3000-2700 BC and is reputed to have been built by giants! Mercifully, nobody has claimed any connection with Atlantis. That is until 2018 when Ryan Pitterson made just such a claim in his book, Judgement of the Nephilim[1620].

Jim Allen in his latest book, Atlantis and the Persian Empire[877], devotes a well-illustrated chapter to a discussion of a number of ‘circular cities’ that existed in ancient Persia and which some commentators claim were the inspiration for Plato’s description of the city of Atlantis. These include the old city of Firuzabad which was divided into 20 sectors by radial spokes as well as Ecbatana and Susa, both noted by Herodotus to have had concentric walls. Understandably, Allen, who promotes the idea of Atlantis in the Andes, has pointed out that many sites on the Altiplano have hilltops surrounded by concentric walls. However, as he seems to realise that to definitively link any of these locations with Plato’s Atlantis a large dollop of speculation was required.

Rodney Castleden compared the layout of Syracuse in Sicily with Plato’s Atlantis noting that the main city “had seen a revolution in its defensive works, with the building of unparalleled lengths of circuit walls punctuated by numerous bastions and towers, displaying the city-state’s power and wealth. The three major districts of the city, Ortygia, Achradina and Tycha, were surrounded by three separate circuit walls; Ortygia itself had three concentric walls, a double wall around the edge and an inner citadel”.[225.179]

Dale Drinnon has an interesting article(d) on the ‘rondels’ of the central Danubian region, which number about 200. Some of these Neolithic features have a lot in common with Plato’s description of the port city of Atlantis. The ubiquity of circular archaeological structures at that time is now quite clear, but they do not demonstrate any relationship with Atlantis.

The late Marcello Cosci based his Atlantis location on his interpretation of aerial images of circular features on Sherbro Island, but as far as I can ascertain this idea has gained little traction.

One of the most remarkable natural examples of concentric features is to be found in modern Mauritania and is known as the Richat Structure or Guelb er Richat. It is such a striking example that it is not surprising that some researchers have tried to link it with Atlantis. Robert deMelo and Jose D.C. Hernandez(o) are two advocates along with George S. Alexander & Natalis Rosen who were struck by the similarity of the Richat feature with Plato’s description and decided to investigate on the ground. Instability in the region prevented this until late 2008 when they visited the site, gathering material for a movie. The film was then finalised and published on their then newly established website in 2010(l), where the one hour video in support of their thesis can be freely downloaded(m).

In 2008, George Sarantitis put forward the idea that the Richat Structure was the location of Atlantis, supporting his contention with an intensive reappraisal of the translation of Plato’s text(n). He developed this further in his Greek language 2010 book, The Apocalypse of a Myth[1470] with an English translation currently in preparation.

However, Ulf Richter has pointed out that Richat is too wide (35 km), too elevated (400metres) and too far from the sea (500 km) to be seriously considered as the location of Atlantis.

A dissertation by Oliver D.Smith has suggested(e) the ancient site of Sesklo in Greece as the location of Atlantis, citing its circularity as an important reason for the identification. However, there are no concentric walls, the site is too small and most importantly, it’s not submerged. Smith later decided that the Atlantis story was a fabrication!(p)

Brad Yoon has claimed that concentric circles are proof of the existence of Atlantis, an idea totally rejected by Jason Colavito(j).

In March 2015, the UK’s MailOnline published a generously illustrated article(g) concerning a number of sites with unexplained concentric circles in China’s Gobi Desert. The article also notes some  superficial similarities with Stonehenge. I will not be surprised if a member of the lunatic fringe concocts an Atlantis theory based on these images. (see right)

superficial similarities with Stonehenge. I will not be surprised if a member of the lunatic fringe concocts an Atlantis theory based on these images. (see right)

Paolo Marini has written Atlantide:Nel cerchio di Stonehenge la chiave dell’enigma (Atlantis: The Circle is the Key to the enigma of Stonehenge) [0713]. The subtitle refers to his contention that the concentric circles of Atlantis are reflected in the layout of Stonehenge!

In 2011 Shoji Yoshinori offered the suggestion that Stonehenge was a 1/24th scale model of Atlantis(f). He includes a fascinating image in the pdf.

This obsession with concentricity has now extended to the interpretation of ancient Scandinavian armoury in particular items such as the Herzsprung Shield(c).

For my part, I wish to question Plato’s description of the layout of Atlantis’ capital city with its vast and perfectly engineered concentric alternating bands of land and sea. This is highly improbable as the layout of cities is invariably determined by the natural topography of the land available to it(h). Plato is describing a city designed by and for a god and his wife and as such his audience would expect it to be perfect and Plato did not let them down. I am therefore suggesting that those passages have been concocted within the parameters of ‘artistic licence’ and should be treated as part of the mythological strand in the narrative, in the same way, that we view the ‘reality’ of Clieto’s five sets of male twins or even the physical existence of Poseidon himself.

Furthermore, Plato was a follower of Pythagoras, who taught that nothing exists without a centre, around which it revolves(k). A concept which may have inspired him to include it in his description of Poseidon’s Atlantis.

(b) Megalithic Lampedusa (archive.org)

(c) https://www.parzifal-ev.de/index.php?id=20

(d) See: Archive 3595

(e) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-3062/

(f) https://www.pipi.jp/~exa/kodai/kaimei/stonehenge_is_small_atrantis_eng.pdf

(i) First Bell Beaker earthwork enclosure found in Spain | ScienceDaily (archive.org) *

(j) https://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/rings-of-power-do-concentric-circles-prove-atlantis-real

(k) Pythagoras and the Mystery of Numbers (archive.org)

(l) Visiting Atlantis | Gateway to a lost world (archive.org)

(m) https://web.archive.org/web/20171022134926/https://visitingatlantis.com/Movie.html

(n) https://platoproject.gr/system-wheels/ https://platoproject.gr/page13.html (offline Nov.2015)

(o) https://blog.world-mysteries.com/science/a-celestial-impact-and-atlantis/ (item 11)

(p) https://shimajournal.org/issues/v10n2/d.-Smith-Shima-v10n2.pdf

Ogyges

Ogyges was the founder and king of Thebes in Greece. During his reign a devastating flood ruined the country to such an extent that it remained without kings until the reign of Cecrops. In a 2002 article(b) in the Times of Malta, Anton Mifsud informed us that “the classical historian Eumalos of Cyrene wrote that the King of Atlantis at the time of the cataclysm was Ogyge whose nephew King Ninus of Babylon lived in the late third millennium BC.”

Some writers have identified the Flood of Ogyges with the Flood of Deucalion. It is more likely that they were separate events and were part of the series of floods noted by Plato [Tim.22 & Crit.111-112].

Frank Joseph in Survivors of Atlantis claimed that Plato in his Laws (Bk.III.677a), dated the Ogygian flood to less than two thousand years before his time.>However, the text is usually translated as “you mean that these things were unknown to the men of those days for thousands upon thousands of years and that one or two thousand years ago some of them were revealed” The Greek word used ‘myrios’ means 10,000 or a large but indefinite number just as the equivalent English word ‘myriad’ is used today.

Unsurprisingly, there is no consensus among other ancient commentators regarding the date of the Ogygian Flood. Varro the Roman writer offers a date of 2136 BC, while Julius Africanus suggests 1793 BC.<

Oliver D.Smith maintained that it was the flood of Ogyges that destroyed Atlantis and argued that this event occurred long before the Flood of Deucalion(a).

P.P.Flambas has suggested[1368] that either Meltwater Pulses 1b or 1c may have led to the inundations remembered by the Greeks as the Flood of Ogyges!

(a) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-3062/ *

(b) https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/on-the-track-of-atlantis.168843

Scranton, Robert Lorentz

Robert Lorentz Scranton (1912-1993) was an American professor of Classical Art at the University of Chicago. He was the author of Greek Walls[1223] in which he endeavoured to develop a stylistic classification system of walls that might assist chronological sequencing.

the author of Greek Walls[1223] in which he endeavoured to develop a stylistic classification system of walls that might assist chronological sequencing.

He wrote a short article(c) with the daring title of “Lost Atlantis  Found Again?” in which he suggests the possibility that Atlantis had been located in Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, Greece. The area is rich in ancient remains including that of a number of canals. However, Scranton was somewhat unsettled by the fact that Plato had described Atlantis as being in the Central Mediterranean, to the west of both Athens and Egypt (see Crit.114c & Tim.25a/b).

Found Again?” in which he suggests the possibility that Atlantis had been located in Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, Greece. The area is rich in ancient remains including that of a number of canals. However, Scranton was somewhat unsettled by the fact that Plato had described Atlantis as being in the Central Mediterranean, to the west of both Athens and Egypt (see Crit.114c & Tim.25a/b).

Scranton’s 1949 article was subsequently made available on Oliver D. Smith’s website(a). Scranton’s Atlantis theory had elements in common with that of Smith’s, who abandoned his Atlantis theory some years ago in favour of a sceptical view of Plato’s narrative.

Joannes Richter, the Dutch linguist, has published a paper, The War against Atlantis, in which he also looks at the idea that Lake Copaïs may have inspired elements of the Atlantis story.

In recent years, excavations in the Lake Copaïs region have revealed more extensive ancient remains than anticipated(b).

A 2021 paper by Therese Ghembaza and David Windell noted that “Since the draining of Lake Copais in Boeotia in the late 19th century archaeological research has revealed Bronze Age hydraulic engineering works of such a scale as to be unique in Europe. Starting in the Middle Helladic period with dams, dikes and polders, the massive extension of the scheme in the Late Helladic period, with large canals and massive dikes, achieved the complete drainage of the lake; a feat not achieved again, despite Hellenistic attempts, until the 20th century.” (d)

An annual Robert L. Scranton Lectureship was established in 1999.

(a) https://atlantisresearch.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/lost-atlantis-found.pdf (now offline – see entry for Oliver D. Smith) See: (c) below

(b) https://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2016/article/rediscovering-a-giant1

(c) Archaeology 2, 1949, p159-162 https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40078396