Ulrich

Atlas Mountains

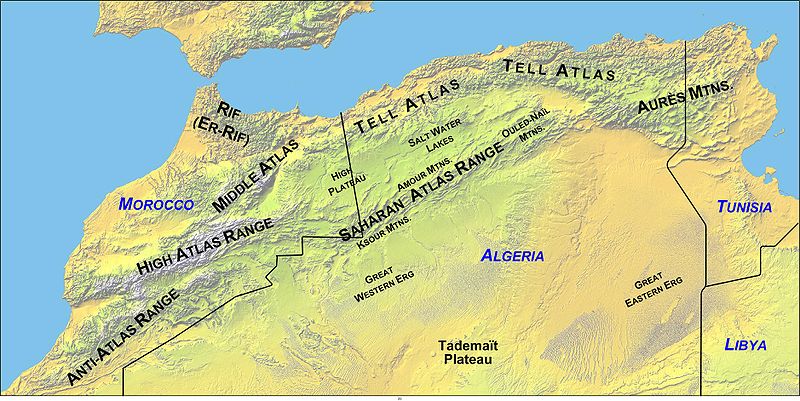

The Atlas Mountains stretch for over 1,500 miles across the Maghreb of North-West Africa, from Morocco through Algeria to  Tunisia. The origin of the name is unclear but seems to be generally accepted as having been named after the Titan.

Tunisia. The origin of the name is unclear but seems to be generally accepted as having been named after the Titan.

Herodotus states (The Histories, Book IV. 42-43) that the inhabitants of ancient Mauretania (modern Morocco) were known as Atlantes and took their name from the nearby mount Atlas. Jean Gattefosse believed that the Atlas Mountains were also known as the Meros and that a large inland sea bounded by the range had been known as both the Meropic and the Atlantic Sea. Furthermore, he contended that Nysa had been a seaport on this inland sea.

The Maghreb, or parts of it, have been identified as the location of Atlantis by a number of commentators. One of the earliest was Ali Bey El Abbassi, who wrote of the Atlas Mountains being the ancient island of Atlantis when what is now the Sahara held a huge interior sea in the centre of Africa.

Ulrich Hofmann concluded his presentation at the 2005 Atlantis Conference with the comment that “based on Plato’s detailed description it can be concluded that Atlantis was most likely identical with the Maghreb.”[629.377] Furthermore, he has proposed that the Algerian Chott-el-Hodna has a ring structure deserving of investigation.

To add a little bit of confusion to the subject, the writer Paul Dunbavin declared[099] that Atlas was a name applied by ancient writers to a number of mountains.

My contention is that the Atlas Mountains of northwest Africa are the mountains referred to by Plato in Critias 118, where he describes the mountains north of the Plain of Atlantis as being the most numerous, the highest and most beautiful. Certainly, within the Mediterranean region, they are the only ones that could match the superlatives used by Plato. In isolation, the Atlas ranges can justifiably be proposed as the peaks referred to by Plato, but there is much more to justify this identification.

The North African climate was slightly wetter in the 2nd & 3rd centuries BC, later, Algeria, Egypt and particularly Tunisia, became the ‘breadbaskets’ of Rome (b). Even today well-irrigated plains in Tunisia can produce two crops a year, usually planted with the autumnal rains and harvested in the early spring and again planted in the spring and harvested in late summer. The Berbers of Morocco produce two crops a year — cereals in winter and vegetables in summer(a).

There is general acceptance that the North African elephants inhabited the Atlas Mountains until they became extinct in Roman times(d)(e). The New Scientist magazine of 7th February 1985(c) outlined the evidence that Tunisia had native elephants until at least the end of the Roman Empire. These were full-sized animals and not to be confused with the remains of pygmy elephants found on some Mediterranean islands. Plato refers to many herds of elephants, which he describes (Critias 115a) as being ‘the largest and most voracious’ of all the animals of Atlantis,>which is not a description of pygmy elephants.<

On top of all that, the only unambiguous geographical clues to the extent of the Atlantean confederation are that it controlled southern Italy as far as Tyrrhenia (Etruria) and northwest Africa as far as Egypt as well as some islands (Tim.25b & Crit.114c). So we have fertile plains with magnificent mountains to the north, inhabited by elephants and controlled by Atlanteans. Q.E.D.

(a) https://www.britannica.com/place/Atlas-Mountains

(b) https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Tunisia

(c) New Scientist 3 Jan.1985 and New Scientist, 7 February.1985 *

(d) https://interesting-africa-facts.com/Africa-Landforms/Atlas-Mountains-Facts.html