E. M. Whishaw

Mining

Mining as a human activity dates back many thousands of years in various parts of the world Recently, the earliest example of mining in the Americas was an iron oxide mine in Chile dating back to around 10,000 BC(a). However, metals, such as gold, silver, copper and tin were not the only material extracted in this way, pigments, flint and salt were also mined in ancient times. The silver mines of Lavrio in Greece employed 29,000 slaves at its peak.

In the Mediterranean itself, Cyprus was an important source of copper, giving the island its name. However, the most important mineral source was probably Sardinia, which for the Romans was one of the three most important sources of metals, along with Spain and Brittany. Although there was a limited amount of tin mined in the Mediterranean region, most came from Spain, Brittany as well as Devon and Cornwall.

Mining in Atlantis is recorded by Plato in Critias 114e where he states that there were many mines producing orichalcum as well as other metals. Mrs. Whishaw contended that the pre-Roman copper mines of Southern Spain was the source of the Atlantean orichalcum.

However, the most extensive ancient mines were probably those of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where copper mining was carried on between 3000 and 1200 BC. It has been guesstimated that up to 1.5 billion pounds of the metal was extracted. It is further speculated that much of this was used to feed the Bronze Age needs of Europe and the Mediterranean(b)(c). This is hotly disputed by local archaeologists(d).

(a) https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-05/uocp-auo051811.php

(b) https://www.grahamhancock.com/forum/WakefieldJS1.php

(c) https://www.superiorreading.com/copperhistory.html

(d) https://www.ramtops.co.uk/copper.html (offline Sept. 2017) (see Archive 2102)

Atlantis in Andalusia

Atlantis in Andalusia: A Study of the Ancient Sun Kingdoms of Spain [053] by Mrs E.M. Whishaw is an account of her 25-year search for Tartessos which she believed she had found under the city of modern Seville.

her 25-year search for Tartessos which she believed she had found under the city of modern Seville.

>An association of Andalusia with Atlantis goes back more than 400 years when José Pellicer linked Atlantis with the Doñana Marshes, an idea that received considerable attention in the 20th century leading to extensive unsuccessful excavations in an area where satellite imagery suggested buried structures.<

Despite of the original title of her book, her view was that Tartessos itself was not Atlantis but one of its colonies. The book describes in detail Mrs Whishaw’s excavations in the town of Niebla, where she lived and the evidence she found which indicate an early culture that she claimed was Atlantean and which was brought from Libya following the drying of the Sahara around 10000 BC. She also investigated the pre-Roman mining that was carried out in the region and concluded that the copper extracted there was the ‘orichalcum’ of Plato’s narrative.

Mrs Whishaw established a museum in Niebla.

Whishaw’s book was reprinted as Atlantis in Spain (Adventures Unlimited Press, Illinois, 1994)

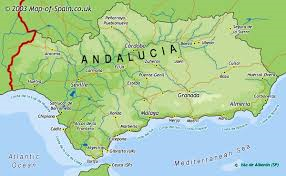

Andalusia *

Andalusia is the second largest of the seventeen autonomous communities of Spain. It is situated in the south of the country with Seville as its capital, which was earlier known as Spal when occupied by the Phoenicians.

However, there is now evidence that near the town of Orce the remains of the earliest hominids to reach Europe have been discovered. These remains have now been dated to 1.6 million years ago according to a November 2023 article on the BBC website(g).

Andalusia is thought to take its name from the Arabic al-andalus – the land of the  Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Andalusia has been identified by a number of investigators as the home of Atlantis. It appears that the earliest proponents of this idea were José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar and Johannes van Gorp in the 17th century. This view was echoed in the 19th century by the historian Francisco Fernández y Gonzáles and subsequently by his son Juan Fernandez Amador de los Rios in 1919. A decade later Mrs E. M. Whishaw published [053] the results of her extensive investigations in the region, particularly in and around Seville. In 1984, Katherine Folliot endorsed this Andalusian location for Atlantis in her book, Atlantis Revisited [054].

Stavros Papamarinopoulos has added his authoritative voice to the claim for an Andalusian Atlantis in a series of six papers(a) presented to a 2010 International Geological Congress in Patras, Greece. He argues that the Andalusian Plain matches the Plain of Atlantis but Plato clearly describes a plain that was 3,000 stadia long and 2,000 stadia wide and even if the unit of measurement was different, the ratio of length to breadth does not match the Andalusian Plain. Furthermore, Plato describes the mountains to the north of the Plain of Atlantis as being “more numerous, higher and more beautiful” than all others. The Sierra Morena to the north of Andalusia does not fit this description. The Sierra Nevada to the south is rather more impressive, but in that region, the most magnificent is the Atlas Mountains of North Africa. As well as that Plato clearly states (Critias 118b) that the Plain of Atlantis faced south while the Andalusian Plain faces west!

During the same period, the German, Adolf Schulten who also spent many years excavating in the area, was also convinced that evidence for Atlantis was to be found in Andalusia. He identified Atlantis with the legendary Tartessos[055].

Dr Rainer W. Kuhne supports the idea that the invasion of the ‘Sea Peoples’ was linked to the war with Atlantis(f), recorded by the Egyptians and he locates Atlantis in Andalusian southern Spain, placing its capital in the valley of the Guadalquivir, south of Seville. In 2003, Werner Wickboldt, a German teacher, declared that he had examined satellite photos of this region and detected structures that very closely resemble those described by Plato in Atlantis. In June 2004, AntiquityVol. 78 No. 300 published an article(b) by Dr Kuhne highlighting Wickboldt’s interpretation of the satellite photos of the area. This article was widely quoted throughout the world’s press. Their chosen site, the Doñana Marshes were linked with Atlantis over 400 years ago by José Pellicer. Kühne also offers additional information on the background to the excavation(e).

However, excavations on the ground revealed that the features identified by Wickboldt were smaller than anticipated and were from the Muslim Period. Local archaeologists have been working on the site for years until renowned self-publicist Richard Freund arrived on the scene, and spent less than a week there, but subsequently ‘allowed’ the media to describe him as leading the excavations.

Although most attention has been focused on the western end of the region, a 2015 theory(d) from Sandra Fernandez places Atlantis in the eastern province of Almeria.

Georgeos Diaz-Montexano has pointed out that Arab commentators referred to Andalus (Andalusia) north of Morocco as being home to a city covered with golden brass.

Quite a number of modern Spanish authors have opted for Andalusia as the home of Atlantis, such as G.C. Aethelman.

Karl Jürgen Hepke has an interesting website(c) where he voices his support for the idea of two Atlantises (see Lewis Spence) one in the Atlantic and the other in Andalusia.

(a) https://www.researchgate.net/search?q=ATLANTIS%20IN%20SPAIN%20I

(b) See Archive 3135

(c) http://web.archive.org/web/20191227133950/http://www.tolos.de/santorin.e.html

(d) https://atlantesdehoy.wordpress.com/2015/08/06/hola-mundo/

(e) The Archaeological Search for Tartessos-Tarshish-Atlantis – Mysteria3000 (archive.org)

(f) Lehrstuhl für theoretische Physik II (archive.org) *

(g) https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20231114-orce-spain-the-site-of-europes-earliest-settlers

Whishaw, Elena Maria

Elena Maria Whishaw (1857-1937/40) was the widow of fellow archaeologist, Bernard Whishaw, whom she succeeded as director of the Anglo-Spanish-American School of Archaeology. Mrs Whishaw devoted a considerable  part of her life to the search for evidence of Atlantis in Andalusia and in particular around the town of Niebla and the city of Seville. However, she was convinced that the region had been colonised by Atlanteans from Libya. She published her discoveries in a 1928 book[053] that has now been reprinted after many years. The region attracted Atlantis seekers following the views of Juan Fernandez Amador de los Rios published in 1919. Adolf Schulten the German archaeologist also spent a considerable time searching in the area during the first half of the 20th century.

part of her life to the search for evidence of Atlantis in Andalusia and in particular around the town of Niebla and the city of Seville. However, she was convinced that the region had been colonised by Atlanteans from Libya. She published her discoveries in a 1928 book[053] that has now been reprinted after many years. The region attracted Atlantis seekers following the views of Juan Fernandez Amador de los Rios published in 1919. Adolf Schulten the German archaeologist also spent a considerable time searching in the area during the first half of the 20th century.

Apart from her interest in history and archaeology, Whishaw also studied local folk arts, in particular embroidery. She lived in Niebla until her death, where she founded a small museum, which unfortunately is now rather neglected.

In 1926 she discovered a prehistoric water conduit, which solved the serious problem of supplying the local population. For all that and other good works, she was named ‘adoptive daughter of Niebla’ in 1927.

In March 2018, the local Niebla Council organised an exhibition of artefacts representative of her life’s work and her contribution to the local community.(a)