Guadalquivir

Doñana Marshes

The Doñana Marshes, a National Park in the valley of the Andalusian Guadalquivir River was linked with Atlantis over 400 years ago by José Pellicer. During the 1920’s George Bonsor and Adolph Schulten searched the area for evidence of Tartessos. After that interest in the marshes waned until a few years ago when Werner Wickboldt identified circular and rectangular features in the Park from satellite images, which he claimed a possibly Atlantean.

The Doñana Marshes, a National Park in the valley of the Andalusian Guadalquivir River was linked with Atlantis over 400 years ago by José Pellicer. During the 1920’s George Bonsor and Adolph Schulten searched the area for evidence of Tartessos. After that interest in the marshes waned until a few years ago when Werner Wickboldt identified circular and rectangular features in the Park from satellite images, which he claimed a possibly Atlantean.

Richard Freund, a professor from the University of Hartford, claims to have led a team to study the area and has had work included in a March 2011 National Geographic documentary, Finding Atlantis. However, Spanish anthropologist Juan Villarias-Robles who has worked on the site for some years has declared that Freund did not lead the investigations on the site and in fact spent less than a week there. Wickboldt’s images turned out to be either smaller than expected or were from the Muslim period. Evidence for Tartessos or Atlantis has not been found.

(b) https://blogs.courant.com/roger_catlin_tv_eye/2011/03/muddying-up-atlantis.html (offline: June 2016) see Archive 2122

Jessen, Professor Otto

Professor Otto Jessen (1891-1951) of Tubingen in Germany was  another of a number of German academics, such as Schulten & Hennig, who, in the early part of the 20th century, were convinced that the answer to the Atlantis mystery lay in Southern Spain. Jessen excavated at the mouth of the Guadalquivir in Spain in a quest for Tartessos, which he believed to be Atlantis[413].

another of a number of German academics, such as Schulten & Hennig, who, in the early part of the 20th century, were convinced that the answer to the Atlantis mystery lay in Southern Spain. Jessen excavated at the mouth of the Guadalquivir in Spain in a quest for Tartessos, which he believed to be Atlantis[413].

*In the early 1920’s he carried studies of the Strait of Gibraltar, the results of which were published in 1927[1564].

Atlantisforschung.de gives a good overview of his life and work(a).

(a) https://atlantisforschung.de/index.php?title=Otto_Jessen*

Carpenter, Rhys

Rhys Carpenter (1889-1980) was an American Professor of Archaeology at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania(a), where he established the School of Classical  Archaeology.

Archaeology.

He expressed the view that the collapse of eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age civilisations was the result of climate change while ignoring the more extensive evidence for concurrent widespread seismic activity in the region. The most recent (August 2013) studies have again pointed to climate change as the culprit(b).

>Carpenter was impressed by Solon’s account of how the archaic Greeks lost their knowledge of writing brought from Egypt and recorded by Plato – “A remarkable detail that should convince the most sceptical of the genuineness of Solon’s conversation with the Saite priest is the latter’s unambiguous statement that the older Greek race had been reduced to an unlettered and uncivilized remnant which, like children, had to learn its letters anew. This claim we now know to be entirely exact, but we have no reason to believe that Plato himself was aware of it.”[220.33]<

In one of his books, Discontinuity in Greek Civilisation[220]. Carpenter declared his conviction that the catastrophic destruction of Santorini was the original inspiration for Plato’s Atlantis narrative.

In another, Beyond the Pillars of Heracles [221] he voiced the opinion that Tartessos was not a city but the name of the river, today’s Guadalquivir, which assisted the extensive mining activities in the area.

In his 1946 work, Folk Tale, Fiction and Saga in the Homeric Epics [1919], available online(e), “Carpenter argued(d) that the Trojan War, far from being a historical event, was in fact a synthesis of many such events involving peoples whose mutual involvement stretched back centuries.”

In 2017, Thorwald C. Franke published a short paper on the Atlantis theories of Rhys Carpenter(c), in which he noted that “Rhys Carpenter started to advocate his hypothesis since about the time of his retirement in 1955. Rhys Carpenter complained that he could not convince any of his colleagues. Here, we are allowed to see a hint to the reason why Carpenter started to advocate his hypothesis only with his retirement, and why not a single colleague agreed: Because it is harmful to a career to advocate such theses.”

(a) Rhys Carpenter (archive.org)

(d) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hisarlik#Troy

(e) https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.74372/page/n9/mode/2up

Blázquez y Delgado-Aguilera, Antonio

Antonio Blázquez y Delgado–Aguilera (1859-1950) was a Spanish historian and geographer, >who, in 1923, edited Avienus’ Ora Maritima, which< identified Tartessos as having been located near the mouth of the Spanish Guadalquivir River, a year before Adolf Schulten published his book on the subject. He was a friend of George Bonsor who also sought Tartessos in the Doñana Marshes.

Antonio Blázquez y Delgado–Aguilera (1859-1950) was a Spanish historian and geographer, >who, in 1923, edited Avienus’ Ora Maritima, which< identified Tartessos as having been located near the mouth of the Spanish Guadalquivir River, a year before Adolf Schulten published his book on the subject. He was a friend of George Bonsor who also sought Tartessos in the Doñana Marshes.

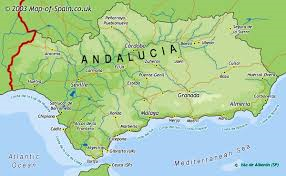

Andalusia

Andalusia is the second largest of the seventeen autonomous communities of Spain. It is situated in the south of the country with Seville as its capital, which was earlier known as Spal when occupied by the Phoenicians.

>However, there is now evidence that near the town of Orce the remains of the earliest hominids to reach Europe have been discovered. These remains have now been dated to 1.6 million years ago according to a November 2023 article on the BBC website(g).<

Andalusia is thought to take its name from the Arabic al-andalus – the land of the  Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Andalusia has been identified by a number of investigators as the home of Atlantis. It appears that the earliest proponents of this idea were José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar and Johannes van Gorp in the 17th century. This view was echoed in the 19th century by the historian Francisco Fernández y Gonzáles and subsequently by his son Juan Fernandez Amador de los Rios in 1919. A decade later Mrs E. M. Whishaw published [053] the results of her extensive investigations in the region, particularly in and around Seville. In 1984, Katherine Folliot endorsed this Andalusian location for Atlantis in her book, Atlantis Revisited [054].

Stavros Papamarinopoulos has added his authoritative voice to the claim for an Andalusian Atlantis in a series of six papers(a) presented to a 2010 International Geological Congress in Patras, Greece. He argues that the Andalusian Plain matches the Plain of Atlantis but Plato clearly describes a plain that was 3,000 stadia long and 2,000 stadia wide and even if the unit of measurement was different, the ratio of length to breadth does not match the Andalusian Plain. Furthermore, Plato describes the mountains to the north of the Plain of Atlantis as being “more numerous, higher and more beautiful” than all others. The Sierra Morena to the north of Andalusia does not fit this description. The Sierra Nevada to the south is rather more impressive, but in that region, the most magnificent is the Atlas Mountains of North Africa. As well as that Plato clearly states (Critias 118b) that the Plain of Atlantis faced south while the Andalusian Plain faces west!

During the same period, the German, Adolf Schulten who also spent many years excavating in the area, was also convinced that evidence for Atlantis was to be found in Andalusia. He identified Atlantis with the legendary Tartessos[055].

Dr Rainer W. Kuhne supports the idea that the invasion of the ‘Sea Peoples’ was linked to the war with Atlantis(f), recorded by the Egyptians and he locates Atlantis in Andalusian southern Spain, placing its capital in the valley of the Guadalquivir, south of Seville. In 2003, Werner Wickboldt, a German teacher, declared that he had examined satellite photos of this region and detected structures that very closely resemble those described by Plato in Atlantis. In June 2004, AntiquityVol. 78 No. 300 published an article(b) by Dr Kuhne highlighting Wickboldt’s interpretation of the satellite photos of the area. This article was widely quoted throughout the world’s press. Their chosen site, the Doñana Marshes were linked with Atlantis over 400 years ago by José Pellicer. Kühne also offers additional information on the background to the excavation(e).

However, excavations on the ground revealed that the features identified by Wickboldt were smaller than anticipated and were from the Muslim Period. Local archaeologists have been working on the site for years until renowned self-publicist Richard Freund arrived on the scene, and spent less than a week there, but subsequently ‘allowed’ the media to describe him as leading the excavations.

Although most attention has been focused on the western end of the region, a 2015 theory(d) from Sandra Fernandez places Atlantis in the eastern province of Almeria.

Georgeos Diaz-Montexano has pointed out that Arab commentators referred to Andalus (Andalusia) north of Morocco as being home to a city covered with golden brass.

Quite a number of modern Spanish authors have opted for Andalusia as the home of Atlantis, such as G.C. Aethelman.

Karl Jürgen Hepke has an interesting website(c) where he voices his support for the idea of two Atlantises (see Lewis Spence) one in the Atlantic and the other in Andalusia.

(a) https://www.researchgate.net/search?q=ATLANTIS%20IN%20SPAIN%20I

(b) See Archive 3135

(c) http://web.archive.org/web/20191227133950/http://www.tolos.de/santorin.e.html

(d) https://atlantesdehoy.wordpress.com/2015/08/06/hola-mundo/

(e) The Archaeological Search for Tartessos-Tarshish-Atlantis – Mysteria3000 (archive.org)

(f) http://t2.physik.uni-dortmund.de/person/kuehne.html

(g) https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20231114-orce-spain-the-site-of-europes-earliest-settlers *

Wickboldt, Werner *

Werner Wickboldt (1943- ) is a teacher and amateur archaeologist, living in Braunschweig, Germany. On January 8, 2003, he gave a lecture on the results of his examination of satellite photos of a region south of Seville, in Parque National Coto de Doñana, he detected structures that very closely resemble those, which Plato described on Atlantis. These structures include a rectangle of size 180 x 90 metres (Temple of Poseidon?) and a square of 180 x 180 meters (Temple of Poseidon and Kleito?). Concentric circles, whose sizes are very close to Plato’s description, surround these two rectangular structures. The largest of these has a radius of 2.5 km. Among the suggested explanations for the structures are; a Roman ‘Castro’, a Viking fort or even a dam for salt production, which is an activity still carried out today in the locality.

In his lecture, Wickboldt went further and claimed that the Atlanteans should be identified as the Sea Peoples(a).

Wickboldt’s discovery inspired Rainer Kühne to develop his theory on Atlantis, which was published in Antiquity. Wickboldt and Kühne hold differing views on various aspects of the Atlantis, which were aired in the comments section of an online forum in 2011(b).

Some debate has developed regarding the actual state of this area in Phoenician times.

It would appear that, during the Roman period, sedimentation brought the mouth of the Guadalquivir about 40 km further south to a position near modern Lebrija. However, in the age of the Tartessians, it was only 13 km south of Seville. If correct this would imply that Wickboldt’s structures were underwater at the time of Plato’s Atlantis. The only way to resolve this issue would be to excavate on the site, but unfortunately, the location is in a national park and at that time any digging was forbidden. Nevertheless, non-intrusive investigative methods were employed to produce additional evidence that might justify a formal archaeological dig. 2010 saw this work begin at the site, with preliminary results indicating that the area was probably hit by a tsunami or a storm flood in the 3rd millennium BC.

The sedimentation argument is not clear-cut, so over a period of millennia when other factors such as seismic activity are brought into the picture, different scenarios are possible. Even if it is not Atlantis or one of its colonies, it would still appear to be a very interesting site, with a story to tell.

In March 2021, Wickboldt published an overpriced 36-page booklet [1822], in which he reprises his contribution to the development of the idea of placing Atlantis in the Doñana Marshes of Andalusia.

(a) “Atlantis lag in Südwest-Spanien” – Atlantisforschung.de (German) *

(b) https://blogs.courant.com/roger_catlin_tv_eye/2011/03/muddying-up-atlantis.html (Link broken March 2020)

.