periplus

Hanno, The Voyage of *

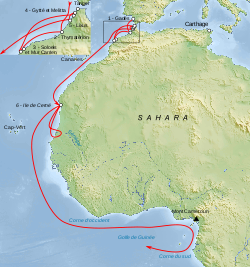

The Voyage of Hanno, the Carthaginian navigator, was undertaken around 500 BC. The general consensus is that his journey took him through the Strait of Gibraltar and along part of the west coast of Africa. A record, or periplus, of the voyage was inscribed on tablets and displayed in the Temple of Baal at Carthage. Richard Hennig  speculated that the contents of the periplus were copied by the Greek historian, Polybius, after the Romans captured Carthage. It did not surface again until the 10th century when a copy, in Greek, was discovered (Codex Heildelbergensis 398) and was not widely published until the 16th century.

speculated that the contents of the periplus were copied by the Greek historian, Polybius, after the Romans captured Carthage. It did not surface again until the 10th century when a copy, in Greek, was discovered (Codex Heildelbergensis 398) and was not widely published until the 16th century.

The 1797 English translation of the periplus by Thomas Falconer along with the original Greek text can be downloaded or read online(h).

Edmund Marsden Goldsmid (1849-?) published a translation of A Treatise On Foreign Languages and Unknown Islands[1348] by Peter Albinus. In footnotes on page 39 he describes Hanno’s periplus as ‘apocryphal’. A number of other commentators(c)(d) have also cast doubts on the authenticity of the Hanno text.

Three years after Ignatius Donnelly published Atlantis, Lord Arundell of Wardour published The Secret of Plato’s Atlantis[0648] intended as a rebuttal of Donnelly’s groundbreaking book. The ‘secret’ referred to in the title is that Plato’s Atlantis story is based on the account we have of the Voyage of Hanno.

Nicolai Zhirov speculated that Hanno may have witnessed ‘the destruction of the southern remnants of Atlantis’, based on some of his descriptions.

Rhys Carpenter dedicated nearly twenty pages to the matter of Hanno commented that ”The modern literature about his (Hanno’s) voyage is unexpectedly large. But it is so filled with disagreement that to summarize it with any thoroughness would be to annul its effectiveness, as the variant opinions would cancel each other out”[221.86]. Carpenter included what he describes as ‘a retranslation of a translation’ of the text.

Further discussion of the text and topography encountered by Hanno can be read in a paper[1483] by Duane W. Roller.

What I find interesting is that so much attention was given to Hanno’s voyage as if it was unique and not what you would expect if Atlantic travel was as commonplace at that time, as many ‘alternative’ history writers claim.

However, even more questionable, is the description of Hanno sailing off “with a fleet of sixty fifty-oared ships, and a large number of men and women to the number of thirty thousand, and with wheat and other provisions.” The problem with this is that the 50-oared ships would have been penteconters, which had limited room for much more than the oarsmen. If we include the crew, an additional 450 persons per ship would have been impossible, in fact, it is unlikely that even the provisions for 500 hundred people could have been accommodated!

Lionel Casson, the author of The Ancient Mariners[1193] commented that “if the whole expedition had been put aboard sixty penteconters, the ships would have quietly settled on the harbour bottom instead of leaving Carthage: a penteconter barely had room to carry a few days’ provisions for its crew, to say nothing of a load of passengers with all the equipment they needed to start a life in a colony.“

The American writer, William H. Russeth, commented(f) on the various interpretations of Hanno’s route, noting that “It is hard for modern scholars to figure out exactly where Hanno travelled, because descriptions changed with each version of the original document and place names change as different cultures exert their influence over the various regions. Even Pliny the Elder, the famous Roman Historian, complained of writers committing errors and adding their own descriptions concerning Hanno’s journey, a bit ironic considering that Romans levelled the temple of Ba’al losing the famous plaque forever.”

George Sarantitis has a more radical interpretation of the Voyage of Hanno, proposing that instead of taking a route along the North African coast and then out into the Atlantic, he proposes that Hanno travelled inland along waterways that no longer exist(e). A 2013 report in New Scientist magazine(n) revealed that 100,000 years ago the Sahara had been home to three large rivers that flowed northward, which probably provided migration routes for our ancestors. Furthermore, if these rivers lasted into the African Humid Period they may be interpreted as support for Sarantitis’ contention regarding Hanno!

He insists that the location of the Pillars of Heracles, as referred to in the narrative, matches the Gulf of Gabes [1470].

The most recent commentary on Hanno’s voyage is on offer by Antonio Usai in his 2014 book, The Pillars of Hercules in Aristotle’s Ecumene[980]. He also has a controversial view of Hanno’s account, claiming that in the “second part, Hanno makes up everything because he does not want to continue that voyage.” (p.24) However, the main objective of Usai’s essays is to demonstrate that the Pillars of Hercules were originally situated in the Central Mediterranean between eastern Tunisia and its Kerkennah Islands.

A 1912 English translation of the text can be read online(a), as well as a modern English translation by Jason Colavito(k).

Another Carthaginian voyager, Himilco, is also thought to have travelled northward in the Atlantic and possibly reached Ireland, referred to as ‘isola sacra’. Unfortunately, his account is no longer available(g).

The controversial epigrapher Barry Fell went so far as to propose that Hanno visited America, citing the Bourne Stone as evidence!(m)*

The livius.org website offers three articles(i) on the text, history and credibility of the surviving periplus together with a commentary.

Another excellent overview of the document is available on the World History Encyclopedia website.(l)

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20040615213109/https://www.jate.u-szeged.hu/~gnovak/f99htHanno.htm

(c) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanno_the_Navigator

(d) https://annoyzview.wordpress.com/2012/04/

(e) https://platoproject.gr/voyage-hanno-Carthaginian/

(f) https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/1033187.William_H_Russeth/blog?page=2 *

(g) https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2011/12/13/high-north-carthaginian-exploration-of-ireland/

(j) BSMQgoYSQYFJ90bRJIhQ&hl=mt&ei=–tuSfNEIaqnAOo_NjHBA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=&ved=CBgQ https://archive.org/details/cu31924031441847

(l) Hanno: Carthaginian Explorer – World History Encyclopedia

(n) NewScientist.com, 16 September 2013, https://tinyurl.com/mg9vcoz

Erythraean Sea

The Erythraean Sea as referred to by Herodotus (Histories Bk I.202) derives its name from the Greek for ‘red’. To the ancient Greeks ‘Erythraean’ was a term used to refer to the Red Sea as well as the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. There is an ancient Persian tradition(a) that the Phoenicians migrated from the shores of the Erythraean Sea. This view is echoed at the very beginning (I.1) of The Histories of Herodotus.

The 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea[1214] (translation by W.H. Schoff) makes it quite clear that the term refers to the region of the Indian Ocean. This can be read online(b).

Michael A. Cahill contends[0819.751] that the Black Sea was the Erythraean Sea referred to in the Book of Enoch.

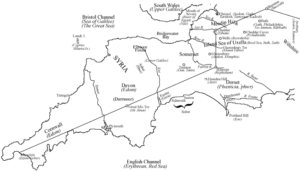

Even more ‘exotic’ is the claim by W.C. Beaumont (see map) that the English Channel was in fact the Erythraean or Red Sea, along with the relocation of many other places mentioned in Exodus to sites in Britain.

Sea, along with the relocation of many other places mentioned in Exodus to sites in Britain.

It is claimed by some writers that Erythraean is an alternative name for the ‘Sea of Atlantis’. R. Cedric Leonard offers the following translation “but the Caspian Sea is by itself, not connected to the other sea. For the sea navigated by the Greeks, also that outside the Pillars called the Atlantis Sea and the Erythraean, are one and the same”. Both Leonard and Anton Mifsud claim that this passage demonstrates that Herodotus identified the Erythraean with the Atlantis Sea. However, a careful reading of the context clearly shows that what Herodotus was describing was the extent to which the world’s oceans were connected, even though the Caspian was landlocked. Africa had already been circumnavigated eastward from Egypt on the instruction of Pharaoh Necho II around 600 BC demonstrating the connection between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Furthermore, the mention of ‘the sea navigated by the Greeks’ is probably a reference to the eastern Mediterranean, placing the Pillars of Heracles in the vicinity of Malta. This would identify the western Mediterranean and/or Tyrrhenian Sea as the ‘Sea of Atlantis’ complementing Plato’s description of Atlantis extending as far as Tyrrhenia and Libya. It is worth noting that Giorgio Grongnet de Vasse envisaged the Island of Atlantis occupying the Gulf of Syrtis off the coast of Libya and designated the sea to the west of Malta as ‘Mare Atlantico Antico’ or the ancient Atlantic Sea.