Greece

Eclipses

Eclipses were often considered to be portents of disaster, however, we are not concerned with such superstitious ideas. However, some records of ancient eclipses have been sufficiently detailed to enable them to be used as chronological anchors. Stavros Papamarinopoulos has used such records to date the Trojan War(d). A 2012 paper by Göran Henriksson also used eclipse data to date that war(e).

>Andis Kaulins has also written an extensive 2004 paper(f) on the Nebra Sky Disk in which he concluded “that the Nebra Sky Disk records the solar eclipse of April 16, 1699, BC for posterity. This interpretation allows not only for a partial explanation of the Nebra Sky Disk but in fact, explains all of the elements found on the disk in an integrated astronomical context which abides by the rules of the burden of proof.”

The biblical story of Joshua and the sun ‘standing still’ has been identified as a description of an eclipse that has now been dated to October 30, 1207 BC(g) in a paper by David Sedley, who notes that the event “also helps pinpoint reigns of Pharaohs Ramesses and Merneptah“<

Encyclopedia Britannica notes(b) that “well over 1,000 individual eclipse records are extant from various parts of the ancient and medieval world. Most known ancient observations of these phenomena originate from only three countries: China, Babylonia, and Greece. No eclipse records appear to have survived from ancient Egypt or India, for example. Whereas virtually all Babylonian accounts are confined to astronomical treatises, those from China and Greece are found in historical and literary works as well. However, the earliest reliable observation is from Ugarit of a total solar eclipse that happened on March 3, 1223, BCE. The first Assyrian record dates from much later, June 15, 763 BCE. From then on, numerous Babylonian and Chinese observations are preserved.”

On the other hand evidence of eclipse prediction does not go back as far, although in the 1960s when the 56 Aubrey Holes at Stonehenge were interpreted as functioning as an eclipse predictor by astronomers Gerald Hawkins and Sir Fred Hoyle, and by amateur enthusiast C.A. `Peter’ Newham, it brought an outcry from the archaeological community.

In 2015, William S. Downey published a paper with the intriguing title of ‘The Cretan middle bronze age ‘Minoan Kernos’ was designed to predict a total solar eclipse and to facilitate a magnetic compass’(a).

The Phaistos Disk, also from Crete has been described as an eclipse predictor as well(c), but this is just one of the many and widely varied theories.

In my opinion, the object we have with the greatest potential as a predictor is the Antikythera Mechanism, dating to around 200 BC. However, nothing so far can be definitively proven as an eclipse predictor.

(b) https://www.britannica.com/science/eclipse/Prediction-and-calculation-of-solar-and-lunar-eclipses

(c) (99+) Counting lunar eclipses using the Phaistos Disk | Richard Heath – Academia.edu

(d) https://www.academia.edu/7806255/A_NEW_ASTRONOMICAL_DATING_OF_THE_TROJAN_WARS_END

(e) https://www.academia.edu/39943416/THE_TROJAN_WAR_DATED_BY_TWO_SOLAR_ECLIPSES

(f) Wayback Machine (archive.org) *

(g) ‘Joshua stopped the sun’ 3,224 years ago today, scientists say | The Times of Israel *

Thrace *

Thrace was an ancient kingdom, which according to Greek mythology was named after Thrax, the son of Ares, the  Greek god of war. Some push back the origins of the Thracians to 3000 BC(b)(c). Homer described the Thracians as allies of Troy. Today Thrace would occupy southeast Bulgaria along with adjacent parts of Greece and Turkey. Some have attempted to link Thrace with Atlantis(a). Abraham Akkerman suggests in Phenomenology of the Winter City[1179.98] that the inspiration for “Plato’s layout of his Ideal City on the island of Atlantis” may be found in Thrace. Keep in mind that situated just north of Thrace was Dacia, part of Romania, another Atlantis candidate.

Greek god of war. Some push back the origins of the Thracians to 3000 BC(b)(c). Homer described the Thracians as allies of Troy. Today Thrace would occupy southeast Bulgaria along with adjacent parts of Greece and Turkey. Some have attempted to link Thrace with Atlantis(a). Abraham Akkerman suggests in Phenomenology of the Winter City[1179.98] that the inspiration for “Plato’s layout of his Ideal City on the island of Atlantis” may be found in Thrace. Keep in mind that situated just north of Thrace was Dacia, part of Romania, another Atlantis candidate.

Also See: Nicolae Densusianu, Romania

(a) atlantis history (archive.org) *

(b) The Enigma of the Thracians and the Orpheus Myth | Ancient Origins (archive.org) *

(c) The Enigma of the Thracians and the Orpheus Myth – Part 2 | Ancient Origins (archive.org) *

Greece

Greece as the home of Atlantis was unknown until the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries when the Minoan Hypothesis began to evolve and is still one of the more popular theories today. Other locations in the Aegean have been proposed by researchers such as Paulino Zamarro and C. A. Djonis as well as three Italian linguists, Facchetti, Negri and Notti, who presented a paper(a) to the 2005 Atlantis Conference outlining their reasons for supporting an Aegean backdrop to the Atlantis story.

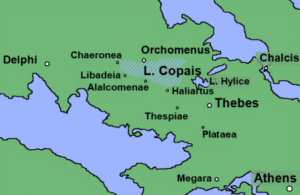

Mainland Greece has also been proposed as home to Atlantis. In the middle of the 20th century R. L. Scranton suggested Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, an idea later modified by Oliver D. Smith, who subsequently completely abandoned the idea of Atlantis as a reality. More recently, it has been proposed that Atlantis was just an allegory of Athens and that its port, ancient Piraeus, was partly the inspiration behind Plato’s description of Atlantis(b). On the other hand, the Dutch linguist, Joannes Richter, also views the Plato’s story as fiction and suggested that “probably Plato used the model of the draining and irrigation system at Lake Copais as a model for the ancient metropolis at the ‘island Atlantis’ in an imaginary war between Athens and Atlantis.”(c)

The sunken Greek cities of Pavlopetri and Helike have also prompted suggestions of a connection with Plato’s lost island.

(a) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/document-250811/

(b) Archive 2887 | (atlantipedia.ie) (see last paragraphs)

(c) https://www.academia.edu/41219454/The_War_against_Atlantis?sm=a (link broken) *

Tyre

Tyre was located in what is modern Lebanon and is considered to have been originally a colony of Sidon. According to  Egyptian records they ruled it during the middle of the second millennium BC, but lost control when their influence in the area declined. Independence brought commercial success that saw Tyre surpass Sidon in wealth and influence and eventually establish its own colonies across the Mediterranean. One of these was Carthage in North Africa, which in time became independent and eventually rivalled the Roman Empire in the west. It also had colonies in Greece and frequently fought with Egypt.

Egyptian records they ruled it during the middle of the second millennium BC, but lost control when their influence in the area declined. Independence brought commercial success that saw Tyre surpass Sidon in wealth and influence and eventually establish its own colonies across the Mediterranean. One of these was Carthage in North Africa, which in time became independent and eventually rivalled the Roman Empire in the west. It also had colonies in Greece and frequently fought with Egypt.

The location of Tyre, on an island with a superb natural harbour and which had great wealth and was supported by its many colonies, has been seen as a mirror of Atlantis. The Old Testament prophecies of Ezekiel, writing around 600 BC, described (26:19, 27: 27-28) the destruction of Tyre in terms that have prompted some to link it with Plato’s description of Atlantis’ demise, written two hundred years later.*The earliest claim that Ezekiel’s Tyrus was a reference to Atlantis was made by Madame Blavatsky in The Secret Doctrine [1495] in 1888.

However, although both J.D. Brady and David Hershiser promote the idea of a linkage between Ezekiel’s Tyrus and Atlantis, they are certain that Tyrus is not the Phoenician city of Tyre. Beyond that, Brady identifies Tyrus/Atlantis with Troy, while Hershiser has placed his Tyrus/Atlantis in the Atlantic just beyond the Strait of Gibraltar(b).

Early in the 20th century Hanns Hörbiger also cited Ezekiel as justification for identifying Tyre as Atlantis.*

Recently, a sunken city has been discovered between Tyre and Sidon and according to its discoverer, Mohammed Sargi, is the 4,000 year old City of Yarmuta referred to in the Tell al-Amarna letters.

Carl Fredrich Baer, the imaginative 18th century writer, proposed a linkage between Tyre and Tyrrhenia. This idea has been  revived recently by the claims of Jaime Manuschevich[468] that the Tyrrhenians were Phoenicians from Tyre. Other supporters of a Tyrrhenian linkage with Tyre are J.D.Brady, Thérêse Ghembaza and most recently Dhani Irwanto. J.S. Gordon also claims[339.241] that Tyre was so named by the Tyrrhenians.

revived recently by the claims of Jaime Manuschevich[468] that the Tyrrhenians were Phoenicians from Tyre. Other supporters of a Tyrrhenian linkage with Tyre are J.D.Brady, Thérêse Ghembaza and most recently Dhani Irwanto. J.S. Gordon also claims[339.241] that Tyre was so named by the Tyrrhenians.

In Greek mythology it is said that Cadmus, son of the Phoenician king Agenor, brought the alphabet to Greece, suggesting a closer connection than generally thought.

J.P. Rambling places the Pillars of Heracles on Insula Herculis, now a sunken island, immediately south of Tyre(a).

(a) https://redefiningatlantis.blogspot.ie/search/label/Heracles

*(b) See: Archive 3395*

Hardy, C. C. M

C. C. M Hardy was a contributor to Egerton Sykes’ Atlantis magazine from its year of inception.

Hardy subscribed to the view that there had been a dam at Gibraltar that was breached around 4500 BC with such a force that it also led to the destruction of a landbridge between Tunisia and Italy.

>In issue 2 of Egerton Sykes’ (Atlantean) Research (July/August 1948) he argued strongly against Ignatius Donnelly’s chosen Atlantis location of Azores. In sharp contrast, he believed that remnants of Atlantis will be found in the seas around Greece.<

In 1966 he investigated the possibility of setting up a University Chair of Atlantean Studies either in the USA or Europe(a). Unfortunately, the idea did not appeal to conservative academia and was consequently shelved. I think that there is even more validity in the idea today.

It is remarkable, therefore, that commencing January 2017 the University of Oxford offered a short course on Plato’s Atlantis. The lecturer is Stephen P. Kershaw, a specialist in Greek mythology(b), which suggests that the lectures may only be concerned with the mythological content of the Atlantis narrative without due regard for any possible historical underpinnings. Kershaw had A Brief History of Atlantis published as a Kindle book in September 2017.

(a) https://www.seachild.net/atlantology/

(b) https://web.archive.org/web/20180315161815/https://www.conted.ox.ac.uk/courses/platos-atlantis

Scranton, Robert Lorentz

Robert Lorentz Scranton (1912-1993) was an American professor of Classical Art at the University of Chicago. He was the author of Greek Walls[1223] in which he endeavoured to develop a stylistic classification system of walls that might assist chronological sequencing.

the author of Greek Walls[1223] in which he endeavoured to develop a stylistic classification system of walls that might assist chronological sequencing.

He wrote a short article(c) with the daring title of “Lost Atlantis  Found Again?” in which he suggests the possibility that Atlantis had been located in Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, Greece. The area is rich in ancient remains including that of a number of canals. However, Scranton was somewhat unsettled by the fact that Plato had described Atlantis as being in the Central Mediterranean, to the west of both Athens and Egypt (see Crit.114c & Tim.25a/b).

Found Again?” in which he suggests the possibility that Atlantis had been located in Lake Copaïs in Boeotia, Greece. The area is rich in ancient remains including that of a number of canals. However, Scranton was somewhat unsettled by the fact that Plato had described Atlantis as being in the Central Mediterranean, to the west of both Athens and Egypt (see Crit.114c & Tim.25a/b).

Scranton’s 1949 article was subsequently made available on Oliver D. Smith’s website(a). Scranton’s Atlantis theory had elements in common with that of Smith’s, who abandoned his Atlantis theory some years ago in favour of a sceptical view of Plato’s narrative.

Joannes Richter, the Dutch linguist, has published a paper, The War against Atlantis, in which he also looks at the idea that Lake Copaïs may have inspired elements of the Atlantis story.

In recent years, excavations in the Lake Copaïs region have revealed more extensive ancient remains than anticipated(b).

A 2021 paper by Therese Ghembaza and David Windell noted that “Since the draining of Lake Copais in Boeotia in the late 19th century archaeological research has revealed Bronze Age hydraulic engineering works of such a scale as to be unique in Europe. Starting in the Middle Helladic period with dams, dikes and polders, the massive extension of the scheme in the Late Helladic period, with large canals and massive dikes, achieved the complete drainage of the lake; a feat not achieved again, despite Hellenistic attempts, until the 20th century.” (d)

An annual Robert L. Scranton Lectureship was established in 1999.

(a) https://atlantisresearch.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/lost-atlantis-found.pdf (now offline – see entry for Oliver D. Smith) See: (c) below

(b) https://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2016/article/rediscovering-a-giant1

(c) Archaeology 2, 1949, p159-162 https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40078396