Oscar Broneer

Late Bronze Age Collapse

Late Bronze Age Collapse of civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC has been variously attributed to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and severe climate change. It is extremely unlikely that all these occurred around the same time through coincidence. Unfortunately, it is not clear to what extent these events were interrelated. As I see it, political upheavals do not lead to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or drought and so can be safely viewed as an effect rather than a cause. Similarly, climate change is just as unlikely to have caused eruptions or seismic activity and so can also be classified as an effect. Consequently, we are left with earthquakes and volcanoes as the prime suspects for the catastrophic turmoil that took place in the Middle East between the 15th and 12th centuries BC. Nevertheless, August 2013 saw further evidence published that also blamed climate change for the demise of Bronze Age civilisations in the region.

In 2022, a fourth possible cause emerged from a genetic research project -disease. The two disease carriers in question were the bacteria Salmonella enterica, which causes typhoid fever, and the infamous Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for the Black Death plague that decimated the population of medieval Europe. These are two of the deadliest microbes human beings have ever encountered, and their presence could have easily triggered significant heavy population loss and rampant social upheaval in ancient societies(d).

Robert Drews[865] dismisses any suggestion that Greece suffered a critical drought around 1200 BC, citing the absence of any supporting reference by Homer or Hesiod as evidence. He proposes that “the transition from chariot to infantry warfare as the primary cause of the Great Kingdoms’ downfall.”

Diodorus Siculus describes a great seismic upheaval in 1250 BC which caused radical topographical changes from the Gulf of Gabes to the Atlantic. (181.16)

This extended period of chaos began around 1450 BC when the eruptions on Thera took place. These caused the well-documented devastation in the region including the ending of the Minoan civilisation and probably the Exodus of the Bible and the Plagues of Egypt as well. According to the Parian Marble, the Flood of Deucalion probably took place around the same time.

Professor Stavros Papamarinopoulos has written of the ‘seismic storm’ that beset the Eastern Mediterranean between 1225 and 1175 BC(a). Similar ideas have been expressed by Amos Nur & Eric H.Cline(b)(c). The invasion of the Sea Peoples recorded by the Egyptians, and parts of Plato’s Atlantis story all appear to have taken place around this same period. Plato refers to a spring on the Athenian acropolis (Crit.112d) that was destroyed during an earthquake. Rainer Kühne notes that this spring only existed for about 25 years but was rediscovered by the Swedish archaeologist, Oscar Broneer, who excavated there from 1959 to 1967. The destruction of the spring and barracks, by an earthquake, was confirmed as having occurring at the end of the 12th century BC. Tony Petrangelo published two interesting, if overlapping, articles in 2020 in which he discussed Broneer’s work on the Acropolis(e)(f).

>A recent review of two books on subject in the journal Antiquity begins with the following preamble;

“The collapse c.1200 BC’ in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean—which saw the end of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Hittite state and its empire and the kingdom of Ugarit—has intrigued archaeologists for decades. As Jesse Millek points out in (his book) Destruction and its impact, the idea of a swathe of near-synchronous destructions across the eastern Mediterranean is central to the narrative of the Late Bronze Age collapse: “destruction stands as the physical manifestation of the end of the Bronze Age” (p.6). Yet whether there was a single collapse marked by a widespread destruction horizon is up for debate.” (g)<

(b) https://academia.edu/355163/2001_Nur_and_Cline_Archaeology_Odyssey_Earthquake_Storms_article (this is a shorter version of (c) below)

(e) https://atlantis.fyi/blog/platos-fountain-on-the-athens-acropolis

(f) A General Program of Defense | Atlantis FYI

(g) Getting closer to the Late Bronze Age collapse in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean, c. 1200 BC | Antiquity | Cambridge Core*

Broneer, Oscar Theodore

Oscar Theodore Broneer (1894-1992) was born in Sweden but moved to the  United States in 1913. Plato described both the Acropolis of Athens as well as Atlantis at the time of their war. He noted that a spring on the Acropolis had been destroyed by an earthquake at that time. Then in 1939, Broneer rediscovered the spring together with evidence that it had been destroyed around 1200 BC, giving us a possible anchor for dating the Atlantis conflict. Broneer’s papers are archived at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

United States in 1913. Plato described both the Acropolis of Athens as well as Atlantis at the time of their war. He noted that a spring on the Acropolis had been destroyed by an earthquake at that time. Then in 1939, Broneer rediscovered the spring together with evidence that it had been destroyed around 1200 BC, giving us a possible anchor for dating the Atlantis conflict. Broneer’s papers are archived at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

>An interesting 2020 review by Tony Petrangelo of Broneer’s work and particularly his discovery of the Acropolis spring, can be found on his Atlantis.FYI website(a)(c).<

Some years ago, Rainer W. Kühne drew attention to the fact that Plato referred to a spring (Crit.112d) on the Acropolis that was destroyed during an earthquake, which he noted had only existed for about 25 years, but was rediscovered by Broneer. This discovery has implications for the historical reality of Atlantis as well as the time of its demise.

The full text of this important illustrated paper is available online(b).

(a) A General Program of Defense | Atlantis FYI

(b) https://www.ascsa.edu.gr/uploads/media/hesperia/146495.pdf

(c) Plato’s Fountain on the Athens Acropolis | Atlantis FYI *

Parian Marble

The Parian Chronicle or Marmor Parium is inscribed on a stele made of high-quality semi-translucent marble found on the Aegean island of Paros, which was greatly prized throughout the Hellenic world during the 1st millennium BC. The site of the quarries is now being turned into an Archaeological Park with the intention of it eventually becoming a World Heritage Site.(o)

Two sections of the stele were found on the island in the 17th century by Thomas Arundell (1586-1643), 2nd Baron Arundell of Wardour, an ancestor of the 12th Baron, John Francis Arundell (1831-1906), who wrote a rebuttal [0648] of Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis theory. A final third section was found on Paros in 1897, silencing claims that the first two were fakes.

As early as 1788, Joseph Robertson (1726-1802) declared the Chronicle to be a modern fake(e) in a lengthy dissertation[1401]+, a claim disproved by the discovery of the final piece over a century later. Even before the third fragment was found, Franke Parker published an in-depth study of the inscription in 1859(f). More recently Peter N. Lindfield has reconstructed the debate that raged around the authenticity of the Parian Marble in the late 1780s(q).

This important register recounts the history of Greece in chronological sequence from 1581 BC until 264 BC and it is reasonably assumed that the latter date was the year it was written.

The first king of Athens is noted on the stele as the mythical Cecrops commencing 1582 BC. This is important as Cecrops is also mentioned by Plato in the Atlantis texts (Critias 110a). This date is far more realistic than the 9,600 BC told to Solon by the Egyptian priests to be the time of the foundation of Athens. The Parian Chronicle seems to have been given little attention regarding the Atlantis mystery. This lack of a direct reference to the Atlantean war may be explained by a comment in Britannica and cited elsewhere(k) which notes(g) that “the author of the Chronicle has given much attention to the festivals, and to poetry and music; thus he has recorded the dates of the establishment of festivals, of the introduction of various kinds of poetry, the births and deaths of the poets, and their victories in contests of poetical skill. On the other hand, important political and military events are often entirely omitted; thus the return of the Heraclidae, Lycurgus, the wars of Messene, Draco, Solon, Cleisthenes, Pericles, the Peloponnesian War and the Thirty Tyrants are not even mentioned.”

Of the philosophers, I note that Anaxagoras, Aristotle and Socrates are listed, but Plato is excluded(m). The high 29% of the entries focused on cultural events and personalities may explain this. So, although the Marble is a valuable document it is very far from being comprehensive.

The Center for Hellenic Studies at Harvard University has published a series of lengthy papers by Andrea Rotstein in which she reviews(i) various aspects of the Parian Marble and commented that “The Parian Marble, as many have noted, may be disappointing as a historical source. People and events that we deem important are missing: Lycurgus, Solon, Cleisthenes, Pericles, and the Peloponnesian wars, do not appear in the extant text.” (j)

Furthermore, Wikipedia lists pages(h) of wars, battles and sieges involving the Greeks, few of which are mentioned in Parian Marble, although quite a number of Alexander’s exploits are recorded. Even the critical naval Battle of Salamis with the Persians is encapsulated on the ‘Marble’ in a mere seven words – “in which battle the Hellenes were victorious”.

Another name mentioned on the stele and by Plato is that of Deucalion. While there is some debate regarding the exact date of the deluge named after him, all commentators agree that it occurred in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. J.G. Bennett(b) has calculated the date of this Flood to around 1478 BC, while Britannica(c) offers 1529 BC. Stavros Papamarinopoulos developed his own king list based on other ancient sources, which generally parallels the Parian content(d).

A further item of interest is the date ascribed to the Trojan War, on the stele, as 1218 BC, but again some controversy surrounds this precise date. While there are a number of flawed details in the Parian Chronicle, probably due to the use of defective sources or perhaps transcription errors, the very specificity of the recorded dates strongly suggests that it was produced in order to offer a real historical record and not merely to recount Greek mythology.

The chronicle is far from being comprehensive, particularly regarding the earlier years when understandably information is more sparse.

I believe that the full implication of the inscriptions for the Atlantis debate has yet to be realised.

A paper in 2018 by George Kokkos took a brief look at some important events confirmed by the Parian Chronicle(p).

It is interesting that Valerius Coucke (1888-1951) a Belgian theologian who had studied the controversial subject of the chronology of the Kingdoms of Judah and Israel, employed the Parian Marble to support his theories(l). Independently, Edwin R. Thiele (1895-1986), an American archaeologist, who engaged in a study of the same period arrived at similar conclusions and is in complete agreement that the start of the divided monarchy began in Nisan of 931 BC, despite using different methods to arrive at this date. This may be interpreted as confirmation of the historical value of the Parian Marble!

A 2020 paper by Tony Petrangelo offers his view of the Parian Marble and its relevance to both the Atlantis Story and the dating of the Trojan War.(n)

>In March 2024, Caleb Howells writing for Greek Reporter also invoked(r) the Parian Marble to support circa 1500 BC as the era in which Atlantis existed. He particularly refers to the mention of Cecrops, Erechtheus, Erichthonius, and Erysichthon by both Plato and the Parian Marble, mythical kings of Athens, thought by some to have been real historical figures.

Although this is far from conclusive, I note that Plato refers to a spring on the Athenian acropolis (Crit.112d) that was destroyed during an earthquake, apparently at the time of Atlantis. Rainer Kühne notes that this spring only existed for about 25 years but was rediscovered by the Swedish archaeologist, Oscar Broneer, who excavated there from 1959 to 1967. The destruction of the spring and barracks, by an earthquake, was confirmed as having occurring at the end of the 12th century BC. This evidence also points to the 2nd millennium BC as the time of Atlantis!<

An English translation of the Parian Marble is available on the internet(a).

[1401]+ https://archive.org/details/parianchronicle00robegoog

(a) https://www.attalus.org/translate/chronicles.html#239.0

(b) https://www.systematics.org/journal/vol1-2/geophysics/systematics-vol1-no2-127-156.htm#9

(e) https://archive.org/details/parianchronicle00robegoog

(f) http://dbooks.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/books/PDFs/590755570.pdf

(g) https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parian-Chronicle

(h) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_involving_Greece

(i) Andrea Rotstein, Literary History in the Parian Marble (archive.org)

(j) 4. The Parian Marble as a Literary Text (archive.org) (Chapter 4)

(k) https://theodora.com/encyclopedia/p/parian_chronicle.html (link broken) See Archive 3638

(l) Valerius Coucke – Wikipedia

(m) https://chs.harvard.edu/chapter/6-literary-history-in-the-parian-marble/ (Chapter 6)

(n) https://atlantis.fyi/blog/the-parian-marble-and-platos-atlantis

(o) Paros Marathi Archaeological Park – Parian Marble Lychnitis

(p) Parian Marble: An incredible ancient chronicle – George Kokkos

(r) When Exactly Is Atlantis Believed to Have Existed? – GreekReporter.com *

Acropolis

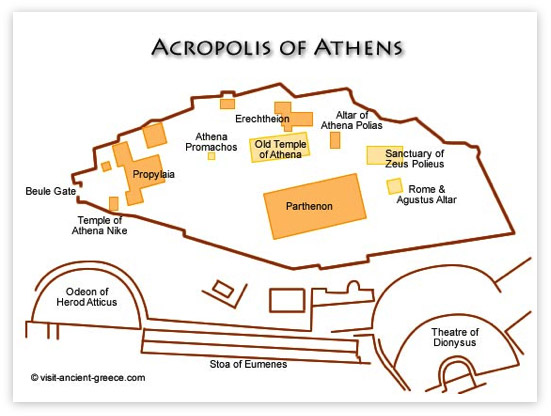

Acropolis is the name given to the central highest position in ancient Greek cities, occupied by the principal religious and civic buildings. The Athenian acropolis was crowned by the magnificent Parthenon, constructed between 447-432 BC. An interesting claim is that the Parthenon was once ‘a riot of colour’(d). Another remarkable feature of the building is that its breadth has been carefully measured at 101.34 feet, which is exactly a second of latitude at the equator(b). The acropolis of Athens is the best known and often erroneously referred to as ‘The’ Acropolis. It is worth noting that the general description of an acropolis is mirrored in Plato’s description of the central buildings of Atlantis  that were also located on elevated ground. Writers such as Jürgen Spanuth[015], Rainer W. Kühne(a) as well as Papamarinopoulos(c) have concluded that the acropolis of Athens provides convincing evidence that the war between Atlantis and Athens took place around 1200 BC. Papamarinopoulos comments further that the “Athens of Critias, is proved a reality of the 12th century B.C., described only by Plato and not by historians, such as Herodotus, Thucydides and others. Analysts of the past have mixed Plato’s fabricated Athens presented in his dialogue Republic with the non-fabricated Athens of his dialogue Critias. This serious error has deflected researchers from their target to interpret Plato’s text efficiently.” (e)

that were also located on elevated ground. Writers such as Jürgen Spanuth[015], Rainer W. Kühne(a) as well as Papamarinopoulos(c) have concluded that the acropolis of Athens provides convincing evidence that the war between Atlantis and Athens took place around 1200 BC. Papamarinopoulos comments further that the “Athens of Critias, is proved a reality of the 12th century B.C., described only by Plato and not by historians, such as Herodotus, Thucydides and others. Analysts of the past have mixed Plato’s fabricated Athens presented in his dialogue Republic with the non-fabricated Athens of his dialogue Critias. This serious error has deflected researchers from their target to interpret Plato’s text efficiently.” (e)

Plato referred to dwellings for warriors (Crit. 112b) situated to the north of the Acropolis that were built in the 15th century BC and were not located again until the earlier part of our 20th century. He also refers to a spring (Critias 112d) that was destroyed during an earthquake. Kühne notes that this spring only existed for about 25 years but was found by the Swedish archaeologist, Oscar Broneer (1894-1992), who excavated there from 1959 to 1967. The destruction of the spring and barracks, by an earthquake, was confirmed as having occurring at the end of the 12th century BC. Plato describes how these catastrophes, of inundation and earthquake, that caused the destruction on the Acropolis, were only survived by those living inland, who were uneducated illiterate people, resulting in the knowledge of writing being lost.

>Papamarinopoulos claims [750.73] that the Athens described by Plato in the Critias is an accurate description of Mycenaean Athens and then leaps to the conclusion that because the details of ancient Athens provided by Plato are correct then it must follow that his depiction of Atlantis is equally reliable! For me this is an unacceptable non sequitur, as Plato lived ln Athens and would have been fully aware of the city’s landmarks and tradition. On the other hand, he had not been to Atlantis, and in fact, he was somewhat vague regarding its actual location. Jason Colavito also took issue with Papamarinopoulos’ contention(f).<

J. Chadwick & Michael Ventris have shown that Linear B was written in an early Greek language and that in Greece it remained in use until around 1200 BC. Subsequently, the Greeks were without a script until the 8th century BC. This date of 1200 BC would appear to match the end of the war between Athens and Atlantis except for Plato’s reference to the earthquake being accompanied by a flood that was the third before the flood of Deucalion, usually dated to at least some centuries before 1200 BC, which implies an earlier date for the Atlantean war.

Collina-Girard in common with many others seems convinced that Atlantis was destroyed around 9500 BC but that Plato’s description of Atlantis is fictional. Collina-Girard’s theory of an Atlantis in the Gibraltar Strait inundated at the end of the Ice Age many thousands of years before the Acropolis existed, forced him to denounce Plato’s Bronze Age descriptions as fiction otherwise he could not justify the exploration of Spartel Island.

(a) Location and Dating of Atlantis (archive.org)

(b) https://www.dioi.org/kn/stade.pdf

(d) https://www.livescience.com/649-parthenon-riot-color.html

(e) https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/geosociety/article/view/11165