Maghreb

Ahaggar Mountains

The Ahaggar Mountains, also known as the Hoggar Mountains are highlands situated in Southern Algeria.

Stephen E. Franklin also opted for an African location for the Garden of Eden, placing it south of the Ahaggar Mountains near the Wadi Tafanasseta) He also claims that Mt. Tahat, the highest peak in the Ahaggars, was the original Atlas mountain referred to by Herodotus as the home of the Atlantes (sometimes Atarantes(b)).

Sprague de Camp noted [194.191] that Paul Borchardt identified ancient Mt. Atlas with the Ahaggar Mountains rather than the Atlas range in the Maghreb!

Lucile Taylor Hansen in The Ancient Atlantic [572], has included a speculative map taken from the Reader’s Digest showing Lake Tritonis, around 11.000 BC, as a megalake covering much of today’s Sahara, with the Ahaggar Mountains turned into an island. Atlantis is shown to the west in the Atlantic.

George Sarantitis, who identifies west Africa as Atlantis has also proposed(c) a vast network of huge inland lakes and waterways in what is now the Sahara, before its desertification. If true, this would probably left the Ahaggars as an island.

Count Khun de Prorock became convinced that Atlantis had a North African origin, specifically on the Hoggar Plateau.He also claimed to have identified the tomb of the legendary Tuareg queen, Tin Hinan, at the oasis of Abalessa in the Hoggar region(d) .

To the east and adjacent to the Ahaggar Mts.is Tassili National Park, where archaeologist Henri Lhote studied the remarkable neolithic cave paintings in Tassili-n’Ajjer [442]. Some of these depicted masked humanoid figures that led Lhote to suggest that they were evidence of prehistoric extraterrestrial visitors. One of these was dubbed the ‘Great Martian God’ and a decade later it was exploited by Erich von Däniken in the promotion of his ‘ancient astronauts’ ideas.

(a) Eight: Adam and Atlas–Eden and the Fall of Atlantis (lordbalto.com)

(b) W. W. How, J. Wells, A Commentary on Herodotus, BOOK IV, chapter 184 (tufts.edu)

(c) The Peninsula of Libya and the Journey of Herodotus – Plato Project (archive.org)

(d) Tin Hinan – Wikipedia *

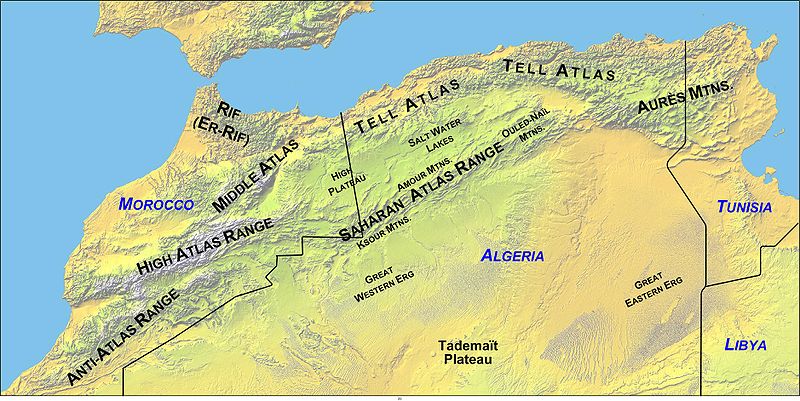

Maghreb, The

The Maghreb is a region of northwest Africa comprising the plains and the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. The term sometimes includes Libya and/or Mauritania and in ancient times also encompassed Moorish Spain.

See: The Atlas Mountains

Agadir

Agadir is a city in the South-West of Morocco. It is situated at the Atlantic end of the Sous-Massa-Draa valley which was considered by Michael Hübner to have been the location of Atlantis(a). The name ‘Agadir’ was identified by him as a variation of Gades, a region of Atlantis, ruled by Gadeiros, the twin brother of Atlas.>As you will see below, another of Atlas’ siblings has also been linked with this region.

Agadir is a city in the South-West of Morocco. It is situated at the Atlantic end of the Sous-Massa-Draa valley which was considered by Michael Hübner to have been the location of Atlantis(a). The name ‘Agadir’ was identified by him as a variation of Gades, a region of Atlantis, ruled by Gadeiros, the twin brother of Atlas.>As you will see below, another of Atlas’ siblings has also been linked with this region.

Atlantisforschung has noted that the German Atlantis researcher Paul Borchardt, who suspected Atlantis to be in the region of Tunisia, claimed that the name Ampheres, one of the kings of Atlantis, was derived from a Berber tribe called ‘Am-Phares’: “They are undoubtedly the Pharusii of Ptolemy (IV, 6, 17) in the Wadi Draa south of the Atlas. Am means people. The name is still very common today. Borchardt thus localizes“, as Ulrich Hofmann, an expert on Borchard’s work, remarks, “ the area of the Ampheres on the southwestern edge of the Maghreb, in modern-day Morocco, south of the 2500m high Atlas Mountains.”(b)<

Keep in mind that Agadir was about 3,300 km away from Athens and 3,700 km from the Nile Delta. Not what you might call ‘easy striking distances’. The relevance of this is discussed more fully in the ‘Invasion‘ entry.

Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains stretch for over 1,500 miles across the Maghreb of North-West Africa, from Morocco through Algeria to  Tunisia. The origin of the name is unclear but seems to be generally accepted as having been named after the Titan.

Tunisia. The origin of the name is unclear but seems to be generally accepted as having been named after the Titan.

Herodotus states (The Histories, Book IV. 42-43) that the inhabitants of ancient Mauretania (modern Morocco) were known as Atlantes and took their name from the nearby mount Atlas. Jean Gattefosse believed that the Atlas Mountains were also known as the Meros and that a large inland sea bounded by the range had been known as both the Meropic and the Atlantic Sea. Furthermore, he contended that Nysa had been a seaport on this inland sea.

The Maghreb, or parts of it, have been identified as the location of Atlantis by a number of commentators. One of the earliest was Ali Bey El Abbassi, who wrote of the Atlas Mountains being the ancient island of Atlantis when what is now the Sahara held a huge interior sea in the centre of Africa.

Ulrich Hofmann concluded his presentation at the 2005 Atlantis Conference with the comment that “based on Plato’s detailed description it can be concluded that Atlantis was most likely identical with the Maghreb.”[629.377] Furthermore, he has proposed that the Algerian Chott-el-Hodna has a ring structure deserving of investigation.

To add a little bit of confusion to the subject, the writer Paul Dunbavin declared[099] that Atlas was a name applied by ancient writers to a number of mountains.

My contention is that the Atlas Mountains of northwest Africa are the mountains referred to by Plato in Critias 118, where he describes the mountains north of the Plain of Atlantis as being the most numerous, the highest and most beautiful. Certainly, within the Mediterranean region, they are the only ones that could match the superlatives used by Plato. In isolation, the Atlas ranges can justifiably be proposed as the peaks referred to by Plato, but there is much more to justify this identification.

The North African climate was slightly wetter in the 2nd & 3rd centuries BC, later, Algeria, Egypt and particularly Tunisia, became the ‘breadbaskets’ of Rome (b). Even today well-irrigated plains in Tunisia can produce two crops a year, usually planted with the autumnal rains and harvested in the early spring and again planted in the spring and harvested in late summer. The Berbers of Morocco produce two crops a year — cereals in winter and vegetables in summer(a).

There is general acceptance that the North African elephants inhabited the Atlas Mountains until they became extinct in Roman times(d)(e). The New Scientist magazine of 7th February 1985(c) outlined the evidence that Tunisia had native elephants until at least the end of the Roman Empire. These were full-sized animals and not to be confused with the remains of pygmy elephants found on some Mediterranean islands. Plato refers to many herds of elephants, which he describes (Critias 115a) as being ‘the largest and most voracious’ of all the animals of Atlantis,>which is not a description of pygmy elephants.<

On top of all that, the only unambiguous geographical clues to the extent of the Atlantean confederation are that it controlled southern Italy as far as Tyrrhenia (Etruria) and northwest Africa as far as Egypt as well as some islands (Tim.25b & Crit.114c). So we have fertile plains with magnificent mountains to the north, inhabited by elephants and controlled by Atlanteans. Q.E.D.

(a) https://www.britannica.com/place/Atlas-Mountains

(b) https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Tunisia

(c) New Scientist 3 Jan.1985 and New Scientist, 7 February.1985 *

(d) https://interesting-africa-facts.com/Africa-Landforms/Atlas-Mountains-Facts.html

Ampheres

Ampheres was one of the first ten kings of Atlantis. According to Plato [Critias 113d] he was the son of Poseidon and Cleito, and the twin brother of Evaemon.

Atlantisforschung noted that the German Atlantis researcher Paul Borchardt, who suspected Atlantis to be in the region of Tunisia, derived the name Ampheres from a Berber tribe called “Am-Phares”: ” They are undoubtedly the Pharusii of Ptolemy (IV, 6, 17) in the Wadi Draa south of the Atlas. Am means people. The name is still very common today. Borchardt thus localizes “, as Ulrich Hofmann, an expert on Borchard’s work, remarks, ‘ the area of ??the Ampheres on the southwestern edge of the Maghreb, in modern-day Morocco, south of the up to 2500m high Atlas Mountains.’(a)

Hübner, Michael

Michael Hübner (1966-2013) was a German researcher who presented to the 2008 Atlantis Conference in Athens, a carefully reasoned argument for placing Atlantis in North-West Africa on the Souss-Massa plain of Morocco. He has gathered and organised a range of geographical details and other clues contained in Plato’s text,which he maintained lead inexorably to Morocco. His paper is now available on the internet(a) and a fuller exposition of his hypothesis has now been published, in German, as Atlantis?:Ein Indizienbeweis [0632], (Atlantis?:Circumstantial Evidence).

Hübner also published a number of video clips on his website in support of his theory. He begins with a lucid demonstration of a Hierarchical Constraint Satisfaction (HCS) approach to solving the mystery. These clips offer a body of evidence which are perhaps the most impressive that I have encountered in the course of many years of research. He matches many of the geographical details recorded by Plato as well as clearly showing rocks coloured red, white and black still in use in buildings in the same area. Hübner also shows possible harbour remains close to Cape Ghir (Rhir), not far north from Agadir (Plato’s ‘Gadeiros’). Although there are still some outstanding questions in my mind, I consider Hübner’s hypothesis one of the more original on offer to date.

However, I perceive some flaws in his search criteria definitions, which in my opinion, have led to an erroneous conclusion, although I think it possible that his Moroccan location may have been partof the Atlantean domain. Furthermore, I consider that his conclusions also conflict with some of the geographical clues provided by Plato.

Nevertheless, I am happy to promote Hübner’s website as a ‘must see’ for any serious student of Atlantology and I had looked forward to the publication of his book in English. In the meanwhile a video on YouTube(b) gives a good overview of his theory.

The 2011 Atlantis Conference saw Hübner present additional evidence(c) in which he translated his HCS method into a series of mathematical formulae.

Tragically, Michael Hübner died in December 2013 as a result of a cycling accident. He left a valuable contribution to Atlantis studies. Mark Adams met Hübner shortly before his death, so in March 2015 when Adams’ book, Meet me in Atlantis, was published, the ensuing media attention probably gave Hübner’s theory more publicity than when he was alive!

Although, I have always been impressed by Hübner’s methodology, my principal objection to his conclusions is based on the fact that all early empires expanded through the invasion of territory that was contiguous or within easy reach by sea. This was a logical requirement for pre-invasion intelligence gathering and for the invasion itself, but also for effective ongoing administrative control. Agadir in Morocco is around 3300 km (2000 miles), by sea, from Athens and so does not match Hübner’s very first ‘constraint’, which requires that “Atlantis should be located within a reasonable range from Athens.” He arbitrarily decided that ‘a reasonable range’ was within a 5,000 km radius based on the fact that the campaigns of Alexander the Great reached a maximum of 4,700 km from Macedonia. However, he seems to have missed the point that Alexander began his attack on the Persian Empire by crossing the Hellespont (Dardanelles), which is less than a mile wide at its narrowest. As is the case with all ancient empires, Alexander expanded his Macedonian empire incrementally, always advancing through various adjacent territories. Alexander’s aim was to conquer the Persian Empire and having done that, he continued with his opportunistic expansionism into India. My point being, that ancient land invasions were always aimed at neighbouring territory, then, if further expansion became possible, it was usually undertaken immediately beyond the newly extended borders. Alexander, did not initially set out to conquer India, but, as he experienced victory after victory, his sense of invincibility grew and so he pushed on until the threat of overwhelming odds ahead and opposition within his own army persuaded him to return home.

Similarly, naval invasions are best carried out over the shortest distances for the obvious logistical reasons of supplies and the risk of inclement weather and rough seas. There are many extreme Atlantis location theories, such as America, Antarctica and the Andes, from which it would have idiotic to launch an attack on Athens, over 3,000 years ago, particularly as there were more attractive and easier places to invade, closer to home, rather than Athens, from where up-to-date pre-invasion military intelligence would have been impossible. Hübner’s Agadir location being 3,300 km from Athens is not as ridiculous as the Transatlantic suggestions, but it is still far too great a distance to make it practical. If expansion had been necessary, nearby territory in Africa or Iberia would, in my opinion, have offered far better targets!

If I’m asked to say what I consider a ‘reasonable striking distance’ for a naval invasion to be, I would hazard a layman’s guess at less than 500 km. When the Romans wiped out Carthage, the used Sicily as a stepping-stone and then had to travel less than 300 km to achieve their goal. But there are many variables to be considered; weather, time of year, terrain and the opposing military, which I think should be left to experts in military history and tactics. However, I must reiterate that 3,300 km is not credible.

My second criticism of Hübner’s presentation is his claim that Plato described Atlantis as being ‘west’ of Tyrrhenia, which is based on his assumption that Atlantis was situated on the Atlantic coast of Morocco and consequently believed that Atlantean territory extended from there eastward until it met Tyrrhenia.

In fact, what Plato said, twice, was that Atlantis extended as far as Tyrrhenia (Timaeus 25b &Critias 114c), The implication being that Tyrrhenian territory, which was situated in central Italy, was adjacent to part of the Atlantean domain, which, I suggest, was located in southern Italy. This would have left the Greek mainland just over 70 km away across the Strait of Otranto, well within striking distance. I think that it is safer to think of the Atlantean alliance having a north/south axis, from Southern Italy, across the Mediterranean, including Sicily together the Maltese and Pelagie Islands and large sections of the Maghreb, including Tunisia and Algeria.

In late 2018, the well-known TV presenter, Andrew Gough, who had previously supported the Minoan Hypothesis, posted a lengthy article on his website(e) endorsing Hübner’s theory.

A graphical demonstration of how HCS works is available on a YouTube clip(d).

>(a) Plato’s Atlantis in South Morocco? (archive.org)<

(b) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MhxsY4GOjpg

(c) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

Reclus, Onésime

Onésime Reclus (1837-1916) was a French geographer who published L’atlantide, pays de l’atlas: Algérie-maroc-tunisie [0523]+ in which he expressed his conviction that Atlantis was located in North-West Africa in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, collectively known as the Maghreb. The Berbers call the Maghreb ‘Tamazgha’, or Land of the Imazighen (plural of Amazigh).

Onésime Reclus (1837-1916) was a French geographer who published L’atlantide, pays de l’atlas: Algérie-maroc-tunisie [0523]+ in which he expressed his conviction that Atlantis was located in North-West Africa in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, collectively known as the Maghreb. The Berbers call the Maghreb ‘Tamazgha’, or Land of the Imazighen (plural of Amazigh).

Reclus is credited with coining the word ‘francophone’.

The Atlantisforschung website commented on Reclus’s book, “newly published in 2013, in which the author locates the ancient Atlantean empire in the Maghreb (mainly in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia ), reveals a thoroughly complex, polydisciplinary treatment of the research subject that suggests a long-term involvement with the matter. Thus Onésime Reclus introduced geographic as well as ethnological, linguistic and historical arguments, such as quotes from classical antiquity authors and later Arab and Jewish historians, in support of his assumptions.(b)“

Reclus had a brother, Elisée (1827-1904), who was an anthropologist, an active anarchist and also a believer in the reality of Atlantis.

[0523]+ https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5804476p.r=atlantide.langFR *

(a) https://atlantisforschung.de/index.php?title=Onésime_Reclus