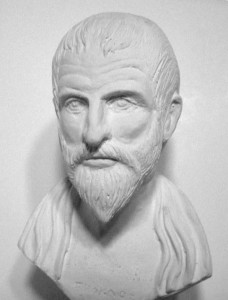

Proclus Lycaeus

Jackson, John Glover

John Glover Jackson (1907-1993) was a renowned Afro-American historian  with a number of major books to his credit, invariably with a strong Afro-centric theme. He was also a devout atheist, a fact that no doubt coloured his many essays on comparative religion. In his 1939 paper, Ethiopia and the Origin of Civilisation(a) , he touches on the subject of Atlantis and clearly accepted the reality of its existence. Jackson quotes Proclus Lycaeus who in turn cited The Ethiopian History of Marcellus as evidence that Atlantis was connected with the history of ancient Ethiopia.

with a number of major books to his credit, invariably with a strong Afro-centric theme. He was also a devout atheist, a fact that no doubt coloured his many essays on comparative religion. In his 1939 paper, Ethiopia and the Origin of Civilisation(a) , he touches on the subject of Atlantis and clearly accepted the reality of its existence. Jackson quotes Proclus Lycaeus who in turn cited The Ethiopian History of Marcellus as evidence that Atlantis was connected with the history of ancient Ethiopia.

(a) https://archive.org/details/EthiopiaAndTheOriginOfCivilization (link broken Jan 2019)

See: Archive 3643

Classical Writers Supporting the Existence of Atlantis

Classical Writers Supporting the Existence of Atlantis

Although many of the early writers are quoted as referring to Plato’s Atlantis or at least alluding to places or events that could be related to his story there is no writer who can be identified as providing unambiguous independent evidence for Atlantis’ existence. One explanation could be that Atlantis may have been known by different names to different peoples in different ages, just as the Roman city of Aquisgranum was later known as Aachen to the Germans and concurrently as Aix-la-Chapelle to the French. However, it would have been quite different if the majority of post-Platonic writers had completely ignored or hotly disputed the veracity of Plato’s tale.

Sprague de Camp, a devout Atlantis sceptic, included 35 pages of references to Atlantis by classical writers in Appendix A to his Lost Continents.[194.288]

Alan Cameron, another Atlantis sceptic, is adamant that ”it is only in modern times that people have taken the Atlantis story seriously, no one did so in antiquity.” Both statements are clearly wrong, as can be seen from the list below and my Chronology of Atlantis Theories and even more comprehensively by Thorwald C. Franke’s Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis (Critical history of the hypotheses on Plato’s Atlantis)[1255].

H.S. Bellamy mentions that about 100 Atlantis references are to be found in post-Platonic classical literature. He also argues that if Plato “had put forward a merely invented story in the Timaeus and Critias Dialogues the reaction of his contemporaries and immediate followers would have been rather more critical.” Thorwald C. Franke echoes this in his Aristotle and Atlantis[880.46]. Bellamy also notes that Sais, where the story originated, was in some ways a Greek city having regular contacts with Athens and should therefore have generated some denial from the priests if the Atlantis tale had been untrue.

Homer(c.8thcent. BC)wrote in his famous Odyssey of a Phoenician island called Scheria that many writers have controversially identified as Atlantis. It could be argued that this is another example of different names being applied to the same location.

Hesiod (c.700 BC) wrote in his Theogonyof the Hesperides located in the west. Some researchers have identified the Hesperides as Atlantis.

Herodotus (c.484-420 BC)regarded by some as the greatest historian of the ancients, wrote about the mysterious island civilization in the Atlantic.

Hellanicus of Lesbos (5th cent. BC) refers to ‘Atlantias’. Timothy Ganz highlights[0376] one line in the few fragments we have from Hellanicus as being particularly noteworthy, “Poseidon mated with Celaeno, and their son Lycus was settled by his father in the Isles of the Blest and made immortal.”

Thucydides (c.460-400 BC)refers to the dominance of the Minoan empire in the Aegean.

Syrianus (died c.437 BC) the Neoplatonist and one-time head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, considered Atlantis to be a historical fact. He wrote a commentary on Timaeus, now lost, but his views are recorded by Proclus.

Eumelos of Cyrene (c.400 BC) was a historian and contemporary of Plato who placed Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean between Libya and Sicily.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Plato’s pupil is constantly quoted in connection with his alleged criticism of Plato’s story. This claim was not made until 1819 when Delambre misinterpreted a commentary on Strabo by Isaac Casaubon. This error has been totally refuted by Thorwald C. Franke[880]. Furthermore, it was Aristotle who stated that the Phoenicians knew of a large island in the Atlantic known as ’Antilia’. Crantor (4th-3rdcent. BC) was Plato’s first editor, who reported visiting Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis. However, Jason Colavito has pointed out that according to Proclus, Crantor was only told by the Egyptian priests that the carved pillars were still in existence.

Crantor (4th-3rd cent. BC) was Plato’s first editor, who reportedly visited Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis. However, Jason Colavito has pointed out(a) that according to Proclus, Crantor was only told by the Egyptian priests that the carved pillars were still in existence.

Theophrastus of Lesbos (370-287 BC) refers to colonies of Atlantis in the sea.

Theopompos of Chios (born c.380 BC), a Greek historian – wrote of the huge size of Atlantis and its cities of Machimum and Eusebius and a golden age free from disease and manual labour. Zhirov states[458.38/9] that Theopompos was considered a fabulist.

Apollodorus of Athens (fl. 140 BC) who was a pupil of Aristarchus of Samothrace (217-145 BC) wrote “Poseidon was very wrathful, and flooded the Thraisian plain, and submerged Attica under sea-water.” Bibliotheca, (III, 14, 1.)

Poseidonius (135-51 BC.) was Cicero’s teacher and wrote, “There were legends that beyond the Hercules Stones there was a huge area which was called “Poseidonis” or “Atlanta”

Diodorus Siculus (1stcent. BC), the Sicilian writer who has made a number of references to Atlantis.

Marcellus (c.100 BC) in his Ethiopic History quoted by Proclus [Zhirov p.40] refers to Atlantis as consisting of seven large and three smaller islands.

Statius Sebosus (c. 50 BC), the Roman geographer, tells us that it was forty days’ sail from the Gorgades (the Cape Verdes) and the Hesperides (the Islands of the Ladies of the West, unquestionably the Caribbean – see Gateway to Atlantis).

Timagenus (c.55 BC), a Greek historian wrote of the war between Atlantis and Europe and noted that some of the ancient tribes in France claimed it as their original home. There is some dispute about the French druids’ claim.

Philo of Alexandria (b.15 BC) also known as Philo Judaeus also accepted the reality of Atlantis’ existence.

Strabo (67 BC-23 AD) in his Geographia stated that he fully agreed with Plato’s assertion that Atlantis was fact rather than fiction.

Plutarch (46-119 AD) wrote about the lost continent in his book Lives, he recorded that both the Phoenicians and the Greeks had visited this island which lay on the west end of the Atlantic.

Pliny the Younger (61-113 AD) is quoted by Frank Joseph as recording the existence of numerous sandbanks outside the Pillars of Hercules as late as 100 AD.

Tertullian (160-220 AD) associated the inundation of Atlantis with Noah’s flood.

Claudius Aelian (170-235 AD) referred to Atlantis in his work The Nature of Animals.

Arnobius (4thcent. AD.), a Christian bishop, is frequently quoted as accepting the reality of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395 AD) [see Marcellinus entry]

Proclus Lycaeus (410-485 AD), a representative of the Neo-Platonic philosophy, recorded that there were several islands west of Europe. The inhabitants of these islands, he proceeds, remember a huge island that they all came from and which had been swallowed up by the sea. He also writes that the Greek philosopher Crantor saw the pillar with the hieroglyphic inscriptions, which told the story of Atlantis.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (6thcent. AD), a Byzantine geographer, in his Topographica Christiana (547 AD) quotes the Greek Historian, Timaeus (345-250 BC) who wrote of the ten kings of Chaldea [Zhirov p.40]. Marjorie Braymer[198.30] wrote that Cosmas was the first to use Plato’s Atlantis to support the veracity of the Bible.

There was little discussion of Atlantis after the 6th century until the Latin translation of Plato’s work by Marsilio Ficino was produced in the 15th century.

(a) https://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/the-first-believer-why-early-atlantis-testimony-is-suspect

Crantor

Crantor (c. 340-275 BC) was born in, Soli, Cilicia, in Asia Minor. He was a philosopher having been a student of Plato’s student Xenocrates Some ancient writers viewed the story of Atlantis as fiction while others believed it was real. Crantor is often cited as an example of a writer who treated the story as a historical fact.

He is recognised as the first commentator on Plato’s work. Although his original text is now lost, fortunately, much is preserved in the writings of fifth century Neoplatonist Proclus Lycaeus, including a commentary on Timaeus.

It is widely accepted that Crantor either travelled to Egypt in person or used an agent to confirm that the Egyptian record of Atlantis was still in existence there.

However, a more critical view has been expressed(a) on the Wikipedia website and widely copied elsewhere. For the sake of balance I have included it here.

His work, a commentary on Plato’s Timaeus, is lost, but Proclus, a Neoplatonist of the fifth century AD, reports on it. The passage in question has been represented in modern literature either as claiming that Crantor actually visited Egypt, had conversations with priests, and saw hieroglyphs confirming the story or as claiming that he learned about them from other visitors to Egypt. Proclus wrote “As for the whole of this account of the Atlanteans, some say that it is unadorned history, such as Crantor, the first commentator on Plato. Crantor also says that Plato’s contemporaries used to criticize him jokingly for not being the inventor of his Republic but copying the institutions of the Egyptians. Plato took these critics seriously enough to assign to the Egyptians this story about the Athenians and Atlanteans, so as to make them say that the Athenians really once lived according to that system.”

The next sentence is often translated as “Crantor adds, that this is testified by the prophets of the Egyptians, who assert that these particulars [which are narrated by Plato] are written on pillars which are still preserved.” But in the original, the sentence starts not with the name Crantor but with the non-specific ‘He’, and whether this referred to Crantor or to Plato is the subject of considerable debate. Proponents of both Atlantis as a myth and Atlantis as history have argued that the word refers to Crantor.

Alan Cameron(b)(c), a fervent sceptic, argues that it should be interpreted as referring to Plato, and that when Proclus writes that “we must bear in mind concerning this whole feat of the Athenians, that it is neither a mere myth nor unadorned history, although some take it as history and others as myth”, he is treating “Crantor’s view as mere personal opinion, nothing more; in fact, he first quotes and then dismisses it as representing one of the two unacceptable extremes”. Cameron also points out that whether he refers to Plato or to Crantor, the statement does not support conclusions such as Otto Muck’s which reads – “Crantor came to Sais and saw there in the temple of Neith the column, completely covered with hieroglyphs, on which the history of Atlantis was recorded. Scholars translated it for him, and he testified that their account fully agreed with Plato’s account of Atlantis” or J. V. Luce’s suggestion that Crantor sent “a special enquiry to Egypt” and that he may simply be referring to Plato’s own claims.

In March 2024, Thorwald C. Franke reviewed an earlier paper from papyrologist Kilian Fleischer regarding the interpretation of Crantor’s comments relating to Plato and the story of Atlantis(d).

(a) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantis

(b) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Cameron_(classical_scholar)

(c) https://www.academia.edu/25684803/Crantor_and_Posidonius_on_Atlantis

(d) Kilian Fleischer on the famous Proclus passage about Crantor and Plato’s Atlantis – Atlantis-Scout *

Proclus *

Proclus Lycaeus (412-487) is considered the last major Greek philosopher.  He came from a rich family in Constantinople. After studying in Alexandria and a brief legal career in Constantinople, he went to Athens to study at the famous School of Philosophy founded 800 years earlier by Plato.

He came from a rich family in Constantinople. After studying in Alexandria and a brief legal career in Constantinople, he went to Athens to study at the famous School of Philosophy founded 800 years earlier by Plato.

He refers to ancient historians mentioning seven small islands in the Outer Ocean (Atlantic) dedicated to Persephone and three larger ones, of which one was 1,000 stadia long and dedicated to Poseidon.

It was Proclus who recorded(d) that Crantor travelled to Sais, as part of his research for Plato’s biography and like Solon was shown the pillars on which the Atlantis story was recorded.

In 1820, Thomas Taylor produced the only English translation that we have of Proclus’ commentary. Andrew Collins has drawn attention[0072.100] to a translation error by Taylor, noted by Alan Cameron(e) and Peter James, which seems to offer a quote from Plato rather than Crantor, which in turn obscures whether it was Crantor or Plato actually travelled to Egypt.

A website(a) dealing with the works of Gerald Massey includes Thomas Taylor’s translation of Proclus’ commentary on Plato’s Timaeus(b).

Taylor notes that in a fragment from a lost book of Proclus, he seems to refer to orichalcum under the name of migma(c).

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20170618062721/https://www.masseiana.org/intro.htm

(b) https://archive.org/details/proclusontimaeus01procuoft (vol..1) *

https://archive.org/details/proclusontimaeus02procuoft (Vol..2) *

(c) https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/flwp/flwp26.htm

(d) In Platonis Theologiam

(e) https://www.academia.edu/25684803/Crantor_and_Posidonius_on_Atlantis?email_work_card=title