Scylla and Charybdis

Zolotukhin, A.I.

Anatoliy Ivanovich Zolotukhin is a Ukranian researcher from the city of Nikolaev (also known as Mykolaiv) an important shipbuilding centre, northwest of Crimea. He is the author of 50 research works on acoustics and turbulence as well as 26 inventions. He is now retired and apart from his ecological interests he has devoted a website with the intriguing title of Homer and Atlantis(a).

acoustics and turbulence as well as 26 inventions. He is now retired and apart from his ecological interests he has devoted a website with the intriguing title of Homer and Atlantis(a).

His main objective is to demonstrate that Homer’s story of Odysseus’ wanderings took place within the Black Sea, but that is not the only controversial claim made by him. He also maintains that the Pillars of Heracles were to be found near Homer’s Scylla & Charybdis and situated in the Bosporus(c).

With regard to Atlantis itself, he locates it in the vicinity of Evpatoria in western Crimea. His 60-page book, Homer. The Immanent Biography[1015] is available on his website(b).

(a) https://homerandatlantis.com/?lang=en

(b) Wayback Machine (archive.org) *

(c) https://homerandatlantis.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Scylla-CharybdisJAH-1.pdf

Strait of Sicily

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

(i) Both the Strait of Messina to the north, between Sicily and Italy together with the Strait of Sicily to the south remained open.

(ii) The Strait of Messina was closed, joining Sicily to Italy, while the Strait of Sicily remained open.

(iii) Both the Strait of Messina and the Strait of Sicily were closed, providing a land bridge between Tunisia and Italy, separating the Eastern from the Western Mediterranean Basins.

I find it strange that what we call today the Strait of Sicily is 90 miles wide. Now the definition of ‘strait’ is a narrow passage of water connecting two large bodies of water. How 90 miles can be described as ‘narrow’ eludes me. Is it possible that we are dealing with a case of mistaken identity and that the ‘Strait of Sicily’ is in fact the Strait of Messina, which is narrow? Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(a) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(b).

Armin Wolf, the German historian, noted(e) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and was quite possibly referring to that same part of Italy which later became known as ‘Magna Graecia’. Robert Fox in The Inner Sea[1168.141] confirms that this long-standing usage of ‘continent’ refers to Italy.

It is worth pointing out that the Strait of Messina is sometimes referred to in ancient literature as the Pillars of Herakles and designates the sea west of this point as the ‘Atlantic Ocean’. Modern writers such as Sergio Frau and Eberhard Zangger, among others, have pointed out that the term ‘Pillars of Herakles’ was applied to more than one location in the Mediterranean in ancient times.

The Strait of Messina is frequently associated with the story of Scylla & Charybdis, which led Arthur R. Weir in a 1959 article(d) to refer to ancient documents, which state that Scylla & Charybdis lie between the Pillars of Heracles.

In 1910, the celebrated Maltese botanist, John Borg, proposed[1132] that Atlantis had been situated on what is now submerged land between Malta and North Africa. A number of other researchers, such as Axel Hausmann and Alberto Arecchi, have expressed similar ideas.

The Strait of Sicily is home to a number of sunken banks, previously exposed during the Last Ice Age. As levels rose most of these disappeared, an event observed by the inhabitants of the region at that time. The MapMistress website(c) has proposed that one of these banks was the legendary Erytheia, the sunken island of the far west. The ‘far west’ later became the Strait of Gibraltar but for the early Greeks it was the Central Mediterranean.

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(d) Atlantis – A New Theory, Science Fantasy #35, June 1959 pp 89-96 https://drive.google.com/file/d/10JTH401O_ew1fs8uhXR9C5IjNDvqnmft/view

>(e) Wayback Machine (archive.org) See Note 5<

Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina is, at its narrowest point, just 2 miles wide. A number of classical writers refer to a time when Sicily was still connected to Italy. In fact legend has it that Heracles was responsible for their separation. However, Cyprian Broodbank has pointed out in his monumental work, The Making of the Middle Sea, that “Today, the Messina strait dividing it (Sicily) from peninsular Italy is a minimum of 3 km (2 miles) wide and 72 metres (235 ft) in depth at its shallowest point. On the face of it, therefore, Sicily and mainland Italy should have fused under full glacial conditions. Yet this spot lies on a plate boundary and has already risen several metres over the last 150 years for which accurate measurements exist. Add a 127,000-71,000-year-old beach now elevated 90m (300ft) above the sea near the strait and we might start to wonder whether Sicily was ever solidly attached to the other land.”[1127.91] Nevertheless, he does suggest that early man possibly had stepping-stones in the form of islets and shallows between the two landmasses.

The Strait of Messina had a reputation in antiquity for having dangerous currents, which are thought to be the inspiration for Homer‘s sea monsters, Scylla and Charybdis. Heinrich Schliemann supported this identification[1243]. The currents there are still very dangerous, but nevertheless the strait is a busy waterway with both commercial and pleasure craft, indicating that the conditions there can be mastered. The hazards were situated at the northern end of the Strait, where today there is a town appropriately called Scilla on the Calabrian side.

The strait is sometimes offered as an earlier site for the Pillars of Heracles prior to the Western Mediterranean becoming more frequently navigated by the ancient Greeks, at which time the term was transferred to the Strait of Gibraltar. Winfried Huf is a keen supporter of ‘Pillars’ having been located at Messina. A constituent part of the Western Mediterranean was the Tyrrhenian Sea, which, for the Greeks, would have been most easily accessed through the Strait of Messina.

The earliest westward expansion of the Greeks was understandably to what became known as Magna Graecia in Sicily and southern Italy. The Phoenician expansion was along the north African coast eventually establishing Carthage at the Strait of Sicily. The ships available at that time were not designed for the open sea, but were usually kept within sight of land. I am inclined to think that the early Greeks would have had the Strait of Messina as the location of their Pillars of Heracles leading to the little known Western Mediterranean (or Tyrrhenian Sea), apparently referred to by some as the ‘Atlantic Sea’, whereas the Strait of Sicily might have led to conflict with the Phoenicians!

It is interesting that from around 330 BC and for nearly a thousand years(b) the Strait of Messina was known as Fretum Siculum, which translates as the Sicilian Strait. Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(c) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139).

>Alexander V. Podossinov in his paper on straits and their significance for the ancients commented “the Carthaginians for a long time did not permit the Greeks to pass through the Straits of Messina and had power over the whole western Mediterranean.”(d)<

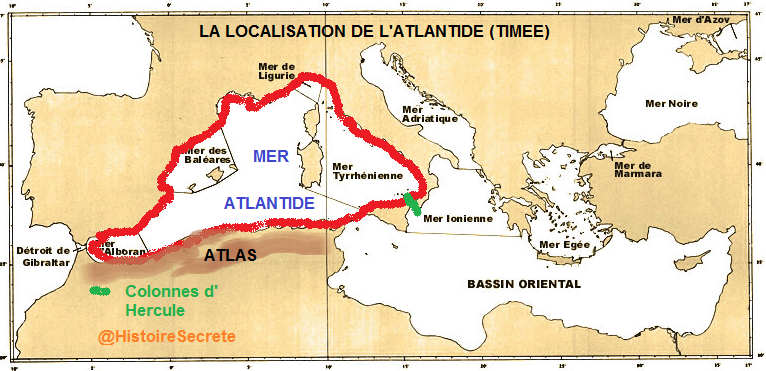

Support for the idea of the Western Mediterranean being the ‘Sea of Atlantis’ with the ‘Pillars’ at the Strait of Messina is presented on a French forum(a), which offers the map below.

(a) https://histoiresecrete.leforum.eu/t716-quelques-questions-se-poser-sur-le-Tim-e-Critias.htm

(b) https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/462494

Scheria

Scheria is the name of a Phaeacian island mentioned by Homer in his Odyssey and identified by some, including Ignatius Donnelly, as Atlantis. Scheria has been noted as only second to Atlantis for the array of locations ascribed to it. For example, Heinrich Schliemann, as well as many ancient and modern commentators, considered Scheria to have been Corfu. K. T. Frost in the early part of the 20th century associated Atlantis with Homer’s Scheria and both with the Minoan Empire, an idea also supported by Walter Leaf(l).

Others, such as Felice Vinci suggest Norway, while Iman Wilkens[610] offers the Canaries.

A recent paper by Gerard Janssen, of Leiden University, also places Scheria in the Canaries, specifically on Lanzarote(f). This is one of an extensive series of papers by Janssen, which links Homer’s geography with locations in the Atlantic(g). An introductory paper(h) might be the best place to start.

An Atlantic location for Homer’s epic poems is advocated by N.R. De Graaf, the Dutch author of the Homeros Explorations website(i). Specifically, he also concluded that Scheria can be identified with Lanzarote in the Canaries concurring with Wilkens and Janssen.

According to Pierluigi Montalbano, his native Sardinia was the Homeric land of the Phaeacians(j). Massimo Pittau offered the same conclusion “However the fact is that the Odyssey- as we have seen before – never mentions Sardinia. How, therefore, can this great and singular historical-documentary inconsistency be overcome? It can be overcome by assuming and saying that the poet of the Odyssey actually mentions Sardinia, but not calling it with his name, which will later become traditional and definitive, but with some other name relating to one of its regions or its population. And this is precisely my point of view, the one I am about to indicate and demonstrate: the poet of the Odyssey mentions Sardinia and its Nuragic civilization when he speaks of the «Scherìa or island of the Phaeacians».”(k)

Armin Wolf (1935- ), the German historian, suggests(b) that Calabria in Southern Italy was Scheria and even more controversially that the Phaeacians were in fact Phoenicians!

Wolf also claims[669.326] that although the country of the Phaeacians is in some translations called an island, the original Greek text never calls it ‘island’ just Scheria, which, Wolf informs us, etymologically means ‘continent’ – perfectly fitting Calabria. Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria they say they are going to the ‘continente’. Wolf puts Scheria in the vicinity of Catanzaro, the capital of Calabria. It has been suggested to me in private correspondence(d) that the etymology of Catanzaro is strongly indicative of a Phoenician influence! Catanzaro is also  known as ‘the city of the two seas’, having the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and the Ionian Sea to the east. It is Wolf’s contention that it was across this isthmus that Odysseus travelled[p.327].

known as ‘the city of the two seas’, having the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and the Ionian Sea to the east. It is Wolf’s contention that it was across this isthmus that Odysseus travelled[p.327].

A further mystery is that, according to Dr Ernst Assmann quoted by Edwin Bjorkman, “both the vessel of Odysseus, as pictured in Greek art, and the term applied to it, are of Phoenician origin.”

Daniel Fleck(a) lists ten similarities between Scheria and Atlantis. Jürgen Spanuth[015] quoted and added to an even more extensive list of comparisons between the two compiled by R. Hennig. Rainer W. Kühne has also written a paper(c) on the similarities. Walter Leaf perceived a connection between the two and wrote accordingly[434]. Edwin Björkman went further and wrote a book[181] that linked Tartessos, Scheria and Atlantis. More recently, Roger Coghill stressed the similarity of Homer’s Scheria to Plato’s Atlantis in The Message of Atlantis [0494].>>Additional comparisons are offered on the coda.io website(n).<<

Ernle Bradford notes that the name Scheria itself is thought by some to be derived from the Phoenician word ‘schera’, which means marketplace, which is not incompatible with Plato’s description of Atlantis as a hive of commercial activity. [1011.204]

Michael MacRae in his Sun Boat: The Odyssey Deciphered[985] also thinks that Scheria could be identified with Atlantis and as such was probably situated at the western end of the Gulf of Cadiz near Portugal’s Cape Vincent. A number of 20th-century researchers such as Sykes and Mertz have placed the travels of Odysseus in the Atlantic. More recently, Gerard Janssen has followed this school of thought and as part of his theories identifies Scheria as the island of Lanzarote in the Canaries (e).

This identification of Scheria with Atlantis has induced Eberhard Zangger, who advocates Atlantis as Troy, to propose that Troy is also Scheria![483]

However, Ernle Bradford, who retraced the voyage of Odysseus, voiced his view that Corfu was the land of the Phaeacians and noted that “the voice of antiquity is almost as unanimous about Scheria being Corfu as it is about the Messina Strait being the home of Scylla and Charybdis.”

A paper by John Black concluded with the following paragraph that fairly sums up what we actually know about the Phaeacians. “Who were the Phaeacians and where was their place of abode? No definite answers and no clues have been found but yet their extraordinary seafaring abilities and the intriguing description by Homer make them appear to be either a fascinating advanced civilization of the past yet to be discovered, or a fiction of the imagination for the sake of a good story. It is worth mentioning that Homer’s description of Troy was also once considered to be a work of fiction. However, the city of Troy has now been discovered, turning myth into reality.” (m)

(a) See: Archive 2087

(b) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(c) (PDF) Did Ulysses Travel to Atlantis? (researchgate.net) *

(d) Private correspondence Jan. 2016

(e) https://www.homerusodyssee.nl/id16.htm

(f) https://www.academia.edu/38347562/ATLANTIC_SCHERIA_AND_THE_FAIAKANS_LANZAROTE_AND_THE_FAYCANS

(g) https://leidenuniv.academia.edu/GerardJanssen

(h) https://www.academia.edu/38537104/ATLANTIC_TROY

(i) https://www.homeros-explorations.nl

(k) Massimo Pittau – The Odyssey and Nuragic Sardinia (www-pittau-it.translate.goog)

(l) Miscellanea Homerica, VI, The Classical Journal, Vol. 23, No. 8 (May, 1928), pp. 615-617 (3 pages)

(m) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/mythic-scheria-and-legendary-phaeacians-001034

(n) https://coda.io/@together/collective-research/homers-oddysey-atlantis-comparison-14 *