Gerard Janssen

Trojan War

The Trojan War, at first sight, may appear to have little to do with the story of Atlantis except that some recent commentators have endeavoured to claim that the war with Atlantis was just a retelling of the Trojan War. The leading proponent of the idea is Eberhard Zangger in his 1992 book The Flood from Heaven [483] and later in a paper(l) published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology. He also argues that survivors of the War became the Sea Peoples, while Frank Joseph contends that the conflict between the Egyptians and the Sea Peoples was part of the Trojan War [108.11].

In an article on the Atlantisforschung website reviewing Zangger’s theory the following paragraph is offered – “What similarities did the Trojan War and the war between Greece and Atlantis have? In both cases, the individual kingdoms in Greece formed a unified army. According to Homer, Greek ships went to the Trojan War in 1186 – according to Plato, Atlantis ruled over 1200 ships. The contingents and weapons are identical (archer, javelin thrower, discus thrower, chariot, bronze weapon, shield). The decisive battle took place overseas on both occasions. In a long period of siege came plague and betrayal. (There is not a word in Plato about a siege or epidemics and treason, dV) In both cases, Greece won the victory. After the Greek forces withdrew, earthquakes and floods struck Greece.“(t)

Steven Sora asserts that the Atlantean war recorded by Plato is a distortion of the Trojan War and contentiously claims that Troy was located on the Iberian Peninsula rather than the more generally accepted Hissarlik in Turkey. Another radical claim is that Troy had been located in Bosnia-Herzegovina or adjacent Croatia, the former by Roberto Salinas Price in 1985[1544], while more recently the latter is promoted by Vedran Sinožic[1543].

Others have located the War in the North Sea or the Baltic. Of these, Iman Wilkens is arguably the best-known advocate of an English location for Troy since 1990. In 2018, Gerard Janssen added further support for Wilkens’ theory(k).

In Where Troy Once Stood [610.18] Wilkens briefly referred to the earliest doubts expressed regarding the location of the Trojan War, starting in 1790 with J.C. Wernsdorf and followed a few years later in 1804 by M. H. Vosz. Then in 1806, Charles deGrave opted for Western Europe. However, it was probably Théophile Cailleux, a Belgian lawyer, whose detailed study of Homeric geography made the greatest inroads into the conventionally accepted Turkish location for Troy.>Andreas Pääbo, who contends that the Odyssey and the Iliad had been written by two different authors, proposed that the inspiration for much of the Trojan War came from ancient Lycia. His paper proposes“that Homer had been a military official in an invasion in his time of a location, also with a citadel, further south on the coast, at what is now southwest Turkey, which was ancient Lycia. Proof of this lies within the Iliad itself, in the author’s many references to Lycia, and in particular to using an alternative name for Scamander – Xanthos – which is the river in Lycia around which the original Lycian civilization developed. This paper(u) studies the details given in the Iliad with geographical information about the location of ancient Lycia to prove this case.”<

However. controversy has surrounded various aspects of the War since the earliest times. Strabo(a) tells us that Aristotle dismissed the matter of the Achaean wall as an invention, a matter that is treated at length by Classics Professor Timothy W. Boyd(b). In fact, the entire account has been the subject of continual criticism. A more nuanced approach to the reality or otherwise of the ‘War’ is offered by Petros Koutoupis(j).

The reality of the Trojan War as related by Homer has been debated for well over a century. There is a view that much of what he wrote was fictional, but that the ancient Greeks accepted this, but at the same time, they possessed a historical account of the war that varied considerably from Homer’s account(f).

Over 130 quotations from the Illiad and Odyssey have been identified in Plato’s writings, suggesting the possibility of him having adopted some of Homer’s nautical data, which may account for Plato’s Atlantean fleet having 1200 ships which might have been a rounding up of Homer’s 1186 ships in the Achaean fleet and an expression of the ultimate in sea power at that time!

Like so many other early historical events, the Trojan War has also generated its fair share of nutty ideas, such as Hans-Peny Hirmenech’s wild suggestion that the rows of standing stones at Carnac marked the tombs of Atlantean soldiers who fought in the Trojan War! Arthur Louis Joquel II proposed that the War was fought between two groups of refugees from the Gobi desert, while Jacques de Mahieu maintained that refugees from Troy fled to America after the War where they are now identified as the Olmecs! In November 2017, an Italian naval archaeologist, Francesco Tiboni, claimed(h). that the Trojan Horse was in reality a ship. This is blamed on the mistranslation of one word in Homer.

In August 2021 it was claimed that remnants of the Trojan Horse had been found. While excavating at the Hisarlik site of Troy, Turkish archaeologists discovered dozens of planks as well as beams up to 15-metre-long.

“The two archaeologists leading the excavation, Boston University professors Christine Morris and Chris Wilson, say that they have a “high level of confidence” that the structure is indeed linked to the legendary horse. They say that all the tests performed up to now have only confirmed their theory.”(o)

“The carbon dating tests and other analyses have all suggested that the wooden pieces and other artefacts date from the 12th or 11th centuries B.C.,” says Professor Morris. “This matches the dates cited for the Trojan War, by many ancient historians like Eratosthenes or Proclus. The assembly of the work also matches the description made by many sources. I don’t want to sound overconfident, but I’m pretty certain that we found the real thing!”

It was not a complete surprise when a few days later Jason Colavito revealed that the story was just a recycled 2014 hoax, which “seven years later, The Greek Reporter picked up the story from a Greek-language website. From there, the Jerusalem Post and International Business Times, both of which have large sections devoted to lightly rewritten clickbait, repeated the story nearly verbatim without checking the facts.”(p)

Various attempts have been made to determine the exact date of the ten-year war, using astronomical dating relating to eclipses noted by Homer. In the 1920s, astronomers Carl Schoch and Paul Neugebauer put the sack of Troy at close to 1190 BC. According to Eratosthenes, the conflict lasted from 1193 to 1184 BC(m).

In 1956, astronomer Michal Kamienski entered the fray with the suggestion that the Trojan War ended circa 1165 BC, suggesting that it may have coincided with the appearance of Halley’s Comet!(n)

An interesting side issue was recorded by Isocrates, who noted that “while they with the combined strength of Hellas found it difficult to take Troy after a siege which lasted ten years, he, on the other hand, in less than as many days, and with a small expedition, easily took the city by storm. After this, he put to death to a man all the princes of the tribes who dwelt along the shores of both continents; and these he could never have destroyed had he not first conquered their armies. When he had done these things, he set up the Pillars of Heracles, as they are called, to be a trophy of victory over the barbarians, a monument to his own valor and the perils he had surmounted, and to mark the bounds of the territory of the Hellenes.” (To Philip. 5.112) This reinforced the idea that there had been more than one location for the Pillars of Herakles(w).

In the 1920s, astronomers Carl Schoch and Paul Neugebauer put the sack of Troy at close to 1190 BC.(q)

In 2008, Constantino Baikouzis and Marcelo O. Magnasco proposed 1178 BC as the date of the eclipse that coincided with the return of Odysseus, ten years after the War(a). Stuart L. Harris published a paper on the Migration & Diffusion website in 2017(g), in which he endorsed the 1190 BC date for the end of the Trojan War.

Nikos Kokkinos, one of Peter James’ co-authors of Centuries of Darkness, published a paper in 2009 questioning the accepted date for the ending of the Trojan War of 1183 BC,(r) put forward by Eratosthenes.

New dating of the end of the Trojan War has been presented by Stavros Papamarinopoulos et al. in a paper(c) now available on the Academia.edu website. Working with astronomical data relating to eclipses in the 2nd millennium BC, they have calculated the ending of the War to have taken place in 1218 BC and Odysseus’ return in 1207 BC.

A 2012 paper by Göran Henriksson also used eclipse data to date that war(v).

What is noteworthy is that virtually all the recent studies of the eclipse data are in agreement that the Trojan War ended near the end of the 13th century BC, which in turn can be linked to archaeological evidence at the Hissarlik site. Perhaps even more important is the 1218 BC date for the Trojan War recorded on the Parian Marble, reinforcing the Papamarinoupolos date.

A 2012 paper by Rodger C. Young & Andrew E. Steinmann added further support for the 1218 BC Trojan War date(s).

Eric Cline has suggested that an earlier date is a possibility, as “scholars are now agreed that even within Homer’s Iliad there are accounts of warriors and events from centuries predating the traditional setting of the Trojan War in 1250 BC” [1005.40].>Cline had previously published The Trojan War: A very Short Introduction [2074], which was enthusiastically reviewed by Petros Koutoupis, who ended with the comment that “It is difficult to believe that such a large amount of detail could be summarized into such a small volume, but Cline is successful in his efforts and provides the reader with a single and concise publication around Homer’s timeless epic.” (x)<

However, an even more radical redating has been strongly advocated by a number of commentators(d)(e) and not without good reason.

(a)Geographica XIII.1.36

(c) https://www.academia.edu/7806255/A_NEW_ASTRONOMICAL_DATING_OF_THE_TROJAN_WARS_END

(d) Archive 2401

(e) https://www.varchive.org/schorr/troy.htm

(f) https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2011/09/06/the-trojan-war-in-greek-historical-sources/

(g) https://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?year=2017&id=509

(j) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/was-there-ever-trojan-war-001737

(k) https://www.homerusodyssee.nl/id12.htm

(l) https://www.academia.edu/25590584/Plato_s_Atlantis_Account_A_Distorted_Recollection_of_the_Trojan_War

(m) Eratosthenes and the Trojan War | Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (archive.org)

(n) Atlantis, Volume 10 No. 3, March 1957

(o) https://greekreporter.com/2021/08/10/archaeologists-discover-trojan-horse-in-turkey/

(p) Newsletter Vol. 19 • Issue 7 • August 15, 2021

(q) https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna25337041

(r) https://www.centuries.co.uk/2009-ancient%20chronography-kokkinos.pdf

(t) Troy – Zangger’s Atlantis – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(v) https://www.academia.edu/39943416/THE_TROJAN_WAR_DATED_BY_TWO_SOLAR_ECLIPSES

(w) https://greekreporter.com/2023/05/25/pillars-hercules-greek-mythology/

(x) Book Review – The Trojan War: A Very Short Introduction by Eric H. Cline (substack.com) *

Wilkens, Iman Jacob

Iman Jacob Wilkens (1936- ) was born in the Netherlands but worked in France as an economist until retiring in 1996. In 1990 he threw a cat among the pigeons when he published Where Troy Once Stood[610] which located  Troy near Cambridge in England and identified Homer’s Trojan War as an extensive conflict in northwest Europe. He follows the work of Belgian lawyer, Théophile Cailleux[393], who presented similar ideas at the end of the 19th century just before Schliemann located his Troy in western Turkey, pushing Cailleux’s theories into obscurity until Wilken’s book a century later. The Cambridge location for Troy has recently been endorsed in a book by Bernard Jones [1638].

Troy near Cambridge in England and identified Homer’s Trojan War as an extensive conflict in northwest Europe. He follows the work of Belgian lawyer, Théophile Cailleux[393], who presented similar ideas at the end of the 19th century just before Schliemann located his Troy in western Turkey, pushing Cailleux’s theories into obscurity until Wilken’s book a century later. The Cambridge location for Troy has recently been endorsed in a book by Bernard Jones [1638].

Wilkens is arguably the best-known proponent of a North Atlantic Troy, which he places in Britain. Another scholar, who argues strongly for Homer’s geographical references being identifiable in the Atlantic, is Gerard Janssen of the University of Leiden, who has published a number of papers on the subject(d).

>It is worth noting that the renowned Moses Finley also found weaknesses in Schliemann’s identification of Hissalik as Troy(f). This is expanded on in Aspects of Antiquity [1953].<

Felice Vinci also gave Homer’s epic a northern European backdrop locating the action in the Baltic[019]. Like Wilkens, he makes a credible case and explains that an invasion of the Eastern Mediterranean by northern Europeans also brought with them their histories as well as place names that were adopted by local writers, such as Homer.

Wilkens claims that the invaders can be identified as the Sea Peoples and were also known as Achaeans and Pelasgians who settled the Aegean and mainland Greece. This matches Spanuth’s identification of the Sea Peoples recorded by the Egyptians as originating in the North Sea. Spanuth went further and claimed that those North Sea Peoples were in fact the Atlanteans.

Wilkens’ original book had a supporting website(a), as does the 2005 edition (b) as well as a companion DVD. A lecture entitled The Trojan Kings of England is also available online(c).

A review of Wilkens’ book by Emilio Spedicato is available online(e).

(a) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20170918084923/https://where-troy-once-stood.co.uk/

(b) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20191121230959/https://www.troy-in-england.co.uk/

(c) http://phdamste.tripod.com/trojan.html

(d) https://leidenuniv.academia.edu/GerardJanssen

Troy

Troy is believed to have been founded by Ilus, son of Troas, giving it the names of both Troy and Ilios (Ilium) with some minor variants.

“According to new evidence obtained from excavations, archaeologists say that the ancient city of Troy in northwestern Turkey may have been more than six centuries older than previously thought. Rüstem Aslan, who is from the Archaeology Department of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (ÇOMU), said that because of fires, earthquakes, and wars, the ancient city of Troy had been destroyed and re-established numerous times throughout the years.” This report pushes the origins of this famous city back to around 3500 BC(s).

Dating Homer’s Troy has produced many problems. Immanuel Velikovsky has drawn attention to some of these difficulties(aa). Ralph S. Pacini endorsed Velikovsky’s conclusion that the matter could only be resolved through a revised chronology. Pacini noted that “the proposed correction of Egyptian chronology produces a veritable flood of synchronisms in the ancient middle east, affirming many of the statements by ancient authors which had been discarded by historians as anachronisms.”(z)

The precise date of the ending of the Trojan War continues to generate comment. A 2012 paper by Rodger C. Young and Andrew E. Steinmann has offered evidence that the conclusion of the conflict occurred in 1208 BC, which agrees with the date recorded on the Parian Marble(ah). This obviously conflicts with the date calculated by Eratosthenes of 1183 BC. A 2009 paper(ai) by Nikos Kokkinos delves into the methodology used by Eratosthenes to arrive at this date. Peter James has listed classical sources that offered competing dates ranging from 1346 BC-1127 BC, although Eratosthenes’ date had more general acceptance by later commentators [46.327] and still has support today.

New dating for the end of the Trojan War has been presented by Stavros Papamarinopoulos et al in a paper(aj) now available on the Academia.edu website. Working with astronomical data relating to eclipses in the 2nd millennium BC, they have calculated the ending of the War to have taken place in 1218 BC and Odysseus’ return in 1207 BC.

The city is generally accepted by modern scholars to have been situated at Hissarlik in what is now northwest Turkey. Confusion over identifying the site as Troy can be traced back to the 1st century AD geographer Strabo, who claimed that Ilion and Troy were two different cities!(t) In the 18th century, many scholars consider the village of Pinarbasi, 10 km south of Hissarlik, as a more likely location for Troy.

The Hisarlik “theory had first been put forward in 1821 by Charles Maclaren, a Scottish newspaper publisher and amateur geologist. Maclaren identified Hisarlik as the Homeric Troy without having visited the region. His theory was based to an extent on observations by the Cambridge professor of mineralogy Edward Daniel Clarke and his assistant John Martin Cripps. In 1801, those gentlemen were the first to have linked the archaeological site at Hisarlik with historic Troy.”(m)

The earliest excavations at Hissarlik began in 1856 by a British naval officer, John Burton. His work was continued in 1863 until 1865 by an amateur researcher, Frank Calvert. It was Calvert who directed Schliemann to Hissarlik and the rest is history(j).

However, some high-profile authorities, such as Sir Moses Finley (1912-1986), have denounced the whole idea of a Trojan War as fiction in his book, The World of Odysseus [1139]. Predating Finley, in 1909, Albert Gruhn argued against Hissarlik as Troy’s location(i).

Not only do details such as the location of Troy or the date of the Trojan War continue to be matters for debate, but surprisingly, whether the immediate cause of the Trojan War, Helen of Troy was ever in Troy or not, is another source of controversy. A paper(ab) by Guy Smoot discusses some of the difficulties. “Odysseus’, Nestor’s and Menelaos’ failures to mention that they saw or found Helen at Troy, combined with the fact that the only two witnesses of her presence are highly untrustworthy and problematic, warrant the conclusion that the Homeric Odyssey casts serious doubts on the version attested in the Homeric Iliad whereby the daughter of Zeus was detained in Troy.”

The Swedish scholar, Martin P. Nilsson (1874-1967) who argued for a Scandinavian origin for the Mycenaeans [1140], also considered the identification of Hissarlik with Homer’s Troy as unproven.

A less dramatic relocation of Troy has been proposed by John Chaple who placed it inland from Hissarlik. This “theory suggests that Hisarlik was part of the first defences of a Trojan homeland that stretched far further inland than is fully appreciated now and probably included the entire valley of the Scamander and its plains (with their distinctive ‘Celtic’ field patterns). That doesn’t mean to say that most of the battles did not take place on the Plain of Troy near Hisarlik as tradition has it but this was only the Trojans ‘front garden’ as it were, yet the main Trojan territory was behind the defensive line of hills and was vastly bigger with the modern town of Ezine its capital – the real Troy.” (af)

Troy as Atlantis is not a commonly held idea, although Strabo, suggested such a link. So it was quite understandable that when Swiss geo-archaeologist, Eberhard Zangger, expressed this view [483] it caused quite a stir. In essence, Zangger proposed(g) that Plato’s story of Atlantis  was a retelling of the Trojan War.

was a retelling of the Trojan War.

For me, the Trojan Atlantis theory makes little sense as Troy was to the northeast of Athens and Plato clearly states that the Atlantean invasion came from the west. In fact, what Plato said was that the invasion came from the ‘Atlantic Sea’ (pelagos). Although there is some disagreement about the location of this Atlantic Sea, all candidates proposed so far are west of both Athens and Egypt.(Tim.24e & Crit. 114c)

Troy would have been well known to Plato, so why did he not simply name them? Furthermore, Plato tells us that the Atlanteans had control of the Mediterranean as far as Libya and Tyrrhenia, which is not a claim that can be made for the Trojans. What about the elephants, the two crops a year or in this scenario, where were the Pillars of Heracles?

A very unusual theory explaining the fall of Troy as a consequence of a plasma discharge is offered by Peter Mungo Jupp on The Thunderbolts Project website(d) together with a video(e).

Zangger proceeded to re-interpret Plato’s text to accommodate a location in North-West Turkey. He contends that the original Atlantis story contains many words that have been critically mistranslated. The Bronze Age Atlantis of Plato matches the Bronze Age Troy. He points out that Plato’s reference to Atlantis as an island is misleading, since, at that time in Egypt where the story originated, they frequently referred to any foreign land as an island. He also compares the position of the bull in the culture of Ancient Anatolia with that of Plato’s Atlantis. He also identifies the plain mentioned in the Atlantis narrative, which is more distant from the sea now, due to silting. Zangger considers these Atlantean/Trojans to have been one of the Sea Peoples who he believes were the Greek-speaking city-states of the Aegean.

Rather strangely, Zangger admits (p.220) that “Troy does not match the description of Atlantis in terms of date, location, size and island character…..”, so the reader can be forgiven for wondering why he wrote his book in the first place. Elsewhere(f), another interesting comment from Zangger was that “One thing is clear, however: the site of Hisarlik has more similarities with Atlantis than with Troy.”

There was considerable academic opposition to Zangger’s theory(a). Arn Strohmeyer wrote a refutation of the idea of a Trojan Atlantis in a German-language book [559].

An American researcher, J. D. Brady, in a somewhat complicated theory, places Atlantis in the Bay of Troy.

In January 2022, Oliver D. Smith who is unhappy with Hisarlik as the location of Troy and dissatisfied with alternatives offered by others, proposed a Bronze Age site, Yenibademli Höyük, on the Aegean island of Imbros(v). His paper was published in the Athens Journal of History (AJH).

To confuse matters further Prof. Arysio Nunes dos Santos, a leading proponent of Atlantis in the South China Sea places Troy in that same region of Asia(b).

Furthermore, the late Philip Coppens reviewed(h) the question marks that still hang over our traditional view of Troy.

Felice Vinci has placed Troy in the Baltic and his views have been endorsed by the American researcher Stuart L. Harris in a number of articles on the excellent Migration and Diffusion website(c). Harris specifically identifies Finland as the location of Troy, which he claims fell in 1283 BC although he subsequently revised this to 1190 BC, which is more in line with conventional thinking. The dating of the Trojan War has spawned its own collection of controversies.

However, the idea of a northern source for Homeric material is not new. In 1918, an English translation of a paper by Carus Sterne (Dr Ernst Ludwig Krause)(1839-1903) was published under the title of The Northern Origin of the Story of Troy(n). Iman Wilkens is arguably the best-known proponent of a North Atlantic Troy, which he places in Britain. Another scholar, who argues strongly for Homer’s geography being identifiable in the Atlantic, is Gerard Janssen of the University of Leiden, who has published a number of papers on the subject(u). Robert John Langdon has endorsed the idea of a northern European location for Troy citing Wilkens and Felice Vinci (w). However, John Esse Larsen is convinced that Homer’s Troy had been situated where the town Bergen on the German island of Rügen(x) is today.

Most recently (May 2019) historian Bernard Jones(q) has joined the ranks of those advocating a Northern European location for Troy in his book, The Discovery of Troy and Its Lost History [1638]. He has also written an article supporting his ideas in the Ancient Origins website(o). For some balance, I suggest that you also read Jason Colavito’s comments(p).

Steven Sora in an article(k) in Atlantis Rising Magazine suggested a site near Lisbon called ‘Troia’ as just possibly the original Troy, as part of his theory that Homer’s epics were based on events that took place in the Atlantic. Two years later, in the same publication, Sora investigated the claim for an Italian Odyssey(l). In the Introduction to The Triumph of the Sea Gods [395], he offers a number of incompatibilities in Homer’s account of the Trojan War with a Mediterranean backdrop.

Roberto Salinas Price (1938-2012) was a Mexican Homeric scholar who caused quite a stir in 1985 in Yugoslavia, as it was then when he claimed that the village of Gabela 15 miles from the Adriatic’s Dalmatian coast in what is now Bosnia-Herzegovina, was the ‘real’ location of Troy in his Homeric Whispers [1544].

More recently another Adriatic location theory has come from the Croatian historian, Vedran Sinožic in his book Naša Troja (Our Troy) [1543]. “After many years of research and exhaustive work on collecting all available information and knowledge, Sinožic provides numerous arguments that prove that the legendary Homer Troy is not located in Hisarlik in Turkey, but is located in the Republic of Croatia – today’s town of Motovun in Istria.” Sinožic who has been developing his theory over the past 30 years has also identified a connection between his Troy and the Celtic world.

Similarly, Zlatko Mandzuka has placed the travels of Odysseus in the Adriatic in his 2014 book, Demystifying the Odyssey[1396].

Fernando Fernández Díaz is a Spanish writer, who has moved Troy to Iberia in his Cómo encontramos la verdadera Troya (y su Cultura material) en Iberia [1810] (How we find the real Troy (and its material Culture) in Iberia.).

Like most high-profile ancient sites, Troy has developed its own mystique, inviting the more imaginative among us to speculate on its associations, including a possible link with Atlantis. Recently, a British genealogist, Anthony Adolph, has proposed that the ancestry of the British can be traced back to Troy in his book Brutus of Troy[1505]. Petros Koutoupis has written a short review of Adolph’s book(ad).

Caleb Howells, a content writer for the Greek Reporter website, among others, has written The Trojan Kings of Britain [2076] due for release in 2024. In it he contends that the legend of Brutus is based on historical facts. However, Adolph came to the conclusion that the story of Brutus is just a myth(ae), whereas Howells supports the opposite viewpoint.

Iman Wilkens delivered a lecture(y) in 1992 titled ‘The Trojan Kings of England’.

It is thought that Schliemann has some doubts about the size of the Troy that he unearthed, as it seemed to fall short of the powerful and prestigious city described by Homer. His misgivings were justified when many decades later the German archaeologist, Manfred Korfmann (1942-2005), resumed excavations at Hissarlik and eventually exposed a Troy that was perhaps ten times greater in extent than Schliemann’s Troy(r).

An anonymous website with the title of The Real City of Troy(ag) began in 2020 and offers regular blogs on the subject of Troy, the most recent (as of Dec. 2023) was published in Nov. 2023. The author is concerned with what appear to be other cities on the Plain of Troy unusually close to Hissarlik!

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20150912081113/https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/1995/95.02.18.html

(b) http://www.atlan.org/articles/atlantis/

(c) http://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?authorid=113

(d) https://www.thunderbolts.info/wp/2013/09/16/troy-homers-plasma-holocaust/

(e) Troy – Homers Plasma holocaust – Episode 1 – the iliad (Destructions 17) (archive.org) *

(f) https://www.moneymuseum.com/pdf/yesterday/03_Antiquity/Atlantis%20en.pdf

(g) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mo-lb2AAGfY

(h) https://www.philipcoppens.com/troy.html or See: Archive 2482

(i) https://www.jstor.org/stable/496830?seq=14#page_scan_tab_contents

(j) https://turkisharchaeonews.net/site/troy

(k) Atlantis Rising Magazine #64 July/Aug 2007 See: Archive 3275

(l) Atlantis Rising Magazine #74 March/April 2009 See: Archive 3276

(m) https://luwianstudies.org/the-investigation-of-troy/

(n) The Open Court magazine. Vol.XXXII (No.8) August 1918. No. 747 See: https://archive.org/stream/opencourt_aug1918caru/opencourt_aug1918caru_djvu.txt

(o) https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/location-troy-0011933

(q) https://www.trojanhistory.com/

(r) Manfred Korfmann, 63, Is Dead; Expanded Excavation at Troy – The New York Times (archive.org)

(t) https://web.archive.org/web/20121130173504/http://www.6millionandcounting.com/articles/article5.php

(u) https://leidenuniv.academia.edu/GerardJanssen

(x) http://odisse.me.uk/troy-the-town-bergen-on-the-island-rugen-2.html

(y) https://phdamste.tripod.com/trojan.html

(z) http://www.mikamar.biz/rainbow11/mikamar/articles/troy.htm (Link broken)

(aa) Troy (varchive.org)

(ab) https://chs.harvard.edu/guy-smoot-did-the-helen-of-the-homeric-odyssey-ever-go-to-troy/

(ac) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-europe/aeneas-troy-0019186

(ad) https://diggingupthepast.substack.com/p/rediscovering-brutus-of-troy-the#details

(ae) https://anthonyadolph.co.uk/brutus-of-troy/

(af) http://www.johnchaple.co.uk/troy.html

(aj) http://www.academia.edu/7806255/A_NEW_ASTRONOMICAL_DATING_OF_THE_TROJAN_WARS_END *

Scheria *

Scheria is the name of a Phaeacian island mentioned by Homer in his Odyssey and identified by some, including Ignatius Donnelly, as Atlantis. Scheria has been noted as only second to Atlantis for the array of locations ascribed to it. For example, Heinrich Schliemann, as well as many ancient and modern commentators, considered Scheria to have been Corfu. K. T. Frost in the early part of the 20th century associated Atlantis with Homer’s Scheria and both with the Minoan Empire, an idea also supported by Walter Leaf(l).

Others, such as Felice Vinci suggest Norway, while Iman Wilkens[610] offers the Canaries.

A recent paper by Gerard Janssen, of Leiden University, also places Scheria in the Canaries, specifically on Lanzarote(f). This is one of an extensive series of papers by Janssen, which links Homer’s geography with locations in the Atlantic(g). An introductory paper(h) might be the best place to start.

An Atlantic location for Homer’s epic poems is advocated by N.R. De Graaf, the Dutch author of the Homeros Explorations website(i). Specifically, he also concluded that Scheria can be identified with Lanzarote in the Canaries concurring with Wilkens and Janssen.

According to Pierluigi Montalbano, his native Sardinia was the Homeric land of the Phaeacians(j). Massimo Pittau offered the same conclusion “However the fact is that the Odyssey- as we have seen before – never mentions Sardinia. How, therefore, can this great and singular historical-documentary inconsistency be overcome? It can be overcome by assuming and saying that the poet of the Odyssey actually mentions Sardinia, but not calling it with his name, which will later become traditional and definitive, but with some other name relating to one of its regions or its population. And this is precisely my point of view, the one I am about to indicate and demonstrate: the poet of the Odyssey mentions Sardinia and its Nuragic civilization when he speaks of the «Scherìa or island of the Phaeacians».”(k)

Armin Wolf (1935- ), the German historian, suggests(b) that Calabria in Southern Italy was Scheria and even more controversially that the Phaeacians were in fact Phoenicians!

Wolf also claims[669.326] that although the country of the Phaeacians is in some translations called an island, the original Greek text never calls it ‘island’ just Scheria, which, Wolf informs us, etymologically means ‘continent’ – perfectly fitting Calabria. Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria they say they are going to the ‘continente’. Wolf puts Scheria in the vicinity of Catanzaro, the capital of Calabria. It has been suggested to me in private correspondence(d) that the etymology of Catanzaro is strongly indicative of a Phoenician influence! Catanzaro is also  known as ‘the city of the two seas’, having the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and the Ionian Sea to the east. It is Wolf’s contention that it was across this isthmus that Odysseus travelled[p.327].

known as ‘the city of the two seas’, having the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and the Ionian Sea to the east. It is Wolf’s contention that it was across this isthmus that Odysseus travelled[p.327].

A further mystery is that, according to Dr Ernst Assmann quoted by Edwin Bjorkman, “both the vessel of Odysseus, as pictured in Greek art, and the term applied to it, are of Phoenician origin.”

Daniel Fleck(a) lists ten similarities between Scheria and Atlantis. Jürgen Spanuth[015] quoted and added to an even more extensive list of comparisons between the two compiled by R. Hennig. Rainer W. Kühne has also written a paper(c) on the similarities. Walter Leaf perceived a connection between the two and wrote accordingly[434]. Edwin Björkman went further and wrote a book[181] that linked Tartessos, Scheria and Atlantis. More recently, Roger Coghill stressed the similarity of Homer’s Scheria to Plato’s Atlantis in The Message of Atlantis [0494]. Ernle Bradford notes that the name Scheria itself is thought by some to be derived from the Phoenician word ‘schera’, which means marketplace, which is not incompatible with Plato’s description of Atlantis as a hive of commercial activity. [1011.204]

Michael MacRae in his Sun Boat: The Odyssey Deciphered[985] also thinks that Scheria could be identified with Atlantis and as such was probably situated at the western end of the Gulf of Cadiz near Portugal’s Cape Vincent. A number of 20th-century researchers such as Sykes and Mertz have placed the travels of Odysseus in the Atlantic. More recently, Gerard Janssen has followed this school of thought and as part of his theories identifies Scheria as the island of Lanzarote in the Canaries (e).

This identification of Scheria with Atlantis has induced Eberhard Zangger, who advocates Atlantis as Troy, to propose that Troy is also Scheria![483]

However, Ernle Bradford, who retraced the voyage of Odysseus, voiced his view that Corfu was the land of the Phaeacians and noted that “the voice of antiquity is almost as unanimous about Scheria being Corfu as it is about the Messina Strait being the home of Scylla and Charybdis.”

A paper by John Black concluded with the following paragraph that fairly sums up what we actually know about the Phaeacians. “Who were the Phaeacians and where was their place of abode? No definite answers and no clues have been found but yet their extraordinary seafaring abilities and the intriguing description by Homer make them appear to be either a fascinating advanced civilization of the past yet to be discovered, or a fiction of the imagination for the sake of a good story. It is worth mentioning that Homer’s description of Troy was also once considered to be a work of fiction. However, the city of Troy has now been discovered, turning myth into reality.” (m)

(a) See: Archive 2087

(b) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(c) https://rxiv.org/pdf/1103.0058v1.pdf

(d) Private correspondence Jan. 2016

(e) https://www.homerusodyssee.nl/id16.htm

(f) https://www.academia.edu/38347562/ATLANTIC_SCHERIA_AND_THE_FAIAKANS_LANZAROTE_AND_THE_FAYCANS

(g) https://leidenuniv.academia.edu/GerardJanssen

(h) https://www.academia.edu/38537104/ATLANTIC_TROY

(i) https://www.homeros-explorations.nl

(k) Massimo Pittau – The Odyssey and Nuragic Sardinia (www-pittau-it.translate.goog)

(l) Miscellanea Homerica, VI, The Classical Journal, Vol. 23, No. 8 (May, 1928), pp. 615-617 (3 pages) *

(m) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/mythic-scheria-and-legendary-phaeacians-001034

Azores

The Azores (Açores) is a group of Portuguese islands in the Atlantic, situated 1,500 km from the mainland. The first recorded instance of their discovery is in 1427 by the Portuguese, although there is some evidence to suggest that the Norse reached the islands 700 years earlier(z). However, they were not the first as recent discoveries have shown clearly that megalith builders and others had occupied the archipelago’s island of Terceira long enough to construct a number of megalithic monuments(aa). Professor Felix Rodrigues has claimed that these structures were stylistically related to European megaliths. The island also has a number of cart ruts, a subject about which Rodrigues et al have published a paper(ad). The significance of the megaliths on Terceira is far greater than might be first thought. Received wisdom has it that apart from coastal hugging, ocean-going vessels were not available until the time of the Phoenicians. The Azorean megaliths suggest otherwise. Furthermore, it throws new light on the possibility of Neolithic and/or Bronze Age visits to America from the Old World. A BBC video(ab) has some interesting images, while for Portuguese speakers a RTP video(ac) has an interview with Professor Rodrigues, who has also written a paper on early Atlantic navigation(ae).

The earliest association of the Azores with Atlantis dates from 1499 when Maximillian I of the Holy Roman Empire (1459-1519) appointed Lukas Fugger vom Reh as the ‘titular’ king of Atlantis. The certificate of appointment nominated the Azores as the remnants of Atlantis. Markus Fugger a descendant of Lukas has published a 2013 paper defending this identification of the Azores with Atlantis(x).

In 2012, the president of the Portuguese Association of Archeological Research (APIA), Nuno Ribeiro, revealed(c) that rock art had been found on the island of Terceira, supporting his belief that human occupation of the Azores predates the arrival of the Portuguese by many thousands of years. A further article(a) in October 2016 expanded on this matter. Ribeiro’s research was trotted out in a more recent documentary from Amazon Prime with the tabloid title of New Atlantis Documentary – Proof that Left Historians Speechless(u), which explores the claim that the Azores are the mountain tops of sunken Atlantis!

However, the Portuguese authorities set up a commission to look into Ribeiro’s contentions and concluded(q) that any perceived remnants of an ancient civilization were either natural rock formations or structures of more modern origin. Nevertheless, as the Epoch Times reports(r) that “Antonieta Costa, a post-doctoral student at the University of Porto in Portugal, remained unconvinced and continued research into the hypothesis that the Azores were inhabited in antiquity and even in prehistory.” In 2013, Costa, published, in English, The Mound of Stones [1967] about the megaliths of the Azores.

It seems to me that the research of Rodrigues, Ribeiro and Costa should be looked at again as a combined study so that the ancient history of the Azores can be more clearly understood and its mysteries resolved.

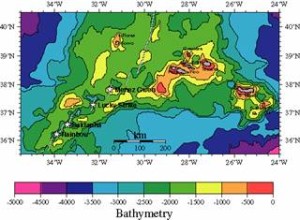

It is thought that the Phoenicians and Etruscans competed for control of the Azores in later years. In 2011, APIA archaeologists reported that they had discovered on Terceira island, a significant number of fourth-century BC Carthaginian temples. They believe the temples were dedicated to the ancient Phoenician/Carthaginian goddess Tanit(c). The Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher, in his 1665 book Mundus Subterraneus, was the first to propose that these islands were the mountain peaks of sunken Atlantis. This view was adopted by Ignatius Donnelly and developed by successive writers and is still supported by many today. The latest recruit is Carl Martin, who is currently working on a book locating Atlantis in the Azores and destroyed around 9620 BC. The late Christian O’Brien was a long-time proponent of the Atlantis in Azores theory. A bathymetric study of the area suggested to O’Brien that the archipelago had been a mid-Atlantic island 480 x 720 km before the end of the last Ice Age. Apart from the inundation caused by the melting of the glaciers, he found evidence that seismic activity caused the southern part of this island to sink to a greater degree than the north. O’Brien pointed out that six areas of hot spring fields (associated with volcanic disturbances) are known in the mid-Atlantic ridge area, and four of them lie in the Kane-Atlantis area close to the Azores.

The late Christian O’Brien was a long-time proponent of the Atlantis in Azores theory. A bathymetric study of the area suggested to O’Brien that the archipelago had been a mid-Atlantic island 480 x 720 km before the end of the last Ice Age. Apart from the inundation caused by the melting of the glaciers, he found evidence that seismic activity caused the southern part of this island to sink to a greater degree than the north. O’Brien pointed out that six areas of hot spring fields (associated with volcanic disturbances) are known in the mid-Atlantic ridge area, and four of them lie in the Kane-Atlantis area close to the Azores.

Klaus Aschenbrenner was originally happy to consider the Azores as a possible location for Atlantis, but further research led him to conclude that this was unlikely(ag).

In 1982 Peter Warlow suggested [135] that a sea-level drop of 200 metres would have created an island as large as England and Wales with the present islands of the Azores as its mountains. However, Rodney Castleden contradicts that idea[225.187] saying that if the sea level was lowered by 200m “the Azores would remain separate islands.” Bathymetric maps of the archipelago, above and on the Internet(g), verify Castleden’s contention. This together with a 1982 paper from P.J.C. Ryall et al, demonstrates more clearly that the Azores are just the summits of volcanic seamounts that rise from an underwater plateau that is 1000 metres below sea level. Professor Ryall and his associates were dealing objectively with the geology of the area and were not promoting any view regarding Atlantis. The geological evidence supporting an Azorean Atlantis is therefore very weak, verging on non-existent.

Andrew Collins, the leading proponent of a Cuban Atlantis, has written a short review of the Azorean Hypothesis(h).

Frank Joseph has offered his views on Atlantis in the Azores in a YouTube video(l).

Nikolai Zhirov recounts in his book[458.363] how Réne Malaise wrote to him regarding a Danish engineer named Frandsen who identified a plateau, 2/3rds the size of Finland, south of the Azores, whose summits were 4,000-5,000m metres higher than it. Adding canals gave Frandsen a configuration that closely matched Plato’s description of Atlantis. Zhirov also noted[p403] that in 1957 a journal entitled Atlantida was published in the Azores.

In 1976, Jürgen Spanuth pointed out[015.249] that the Azores are not the mountain peaks of a sunken continent but are instead volcanic rock created through an eruption. He quotes similar sentiments expressed by Hans Pettersson. A 2003 paper(b) by four French scientists demonstrated that the Azores had been greatly enlarged during the last Ice Age. However, showing that the Azores were more extensive is not disputed, but it in no way demonstrates that it was the location of Atlantis. In fact, Plato’s description of the magnificent mountains to the north and the mud shoals that were still a hazard in Plato’s day do not match the Azores. The geologist, Darby South, strongly denied that the Azores could have been the location of Atlantis according to a couple of articles posted on the internet some years ago(a). However, natives of the archipelago are quite happy to assert a link with Atlantis, as travel writer David Yeadon found on a visit there(d).

Nevertheless, advocates of Atlantis in the Azores must accept that when the Portuguese arrived on the island in the 15th century they were found to be uninhabited and without any evidence of an earlier advanced civilisation there, such as described by Plato. Initially, the only hint of earlier visitors was some 3rd-century BC coins from Carthage discovered on the island of Corvo. However, in recent years Bronze Age rock art(f) and what is described as a Carthaginian temple(e) have both been discovered on the island of Terceira.

Otto Muck among others was certain that the enlarged Azores had deflected the Gulf Stream during the Ice Age, contributing to the extent of the Western European glaciation. However, a 2016 report(m) from the Center for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Climate and Environment (CAGE) offered evidence that the Gulf Stream was not interrupted during the last Ice Age, which would seem to undermine one of Muck’s principal claims.

among others was certain that the enlarged Azores had deflected the Gulf Stream during the Ice Age, contributing to the extent of the Western European glaciation. However, a 2016 report(m) from the Center for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Climate and Environment (CAGE) offered evidence that the Gulf Stream was not interrupted during the last Ice Age, which would seem to undermine one of Muck’s principal claims.

Nevertheless, it is still far from clear what caused the ending of the last Ice Age. A number of writers including Muck speculated that an asteroidal impact in the Atlantic was responsible. When the Azores were discovered in the 15th century they were uninhabited and without any evidence of an earlier civilisation. It can be reasonably argued that since the Azores today are just the mountain peaks of a larger mainly submerged island, any remains would be more likely to be found on the plains and estuaries that are now underwater. One undeveloped theory is that the name ‘Azores’ might be linked to the ninth king of Atlantis, Azaes, listed by Plato. This idea is supported by the linguist Dr Vamos-Toth Bator. However, a Portuguese correspondent has pointed out that the Azores is named after a goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) commonly found on the islands and portrayed on the regional flag. The renowned writer, Dennis Wheatley, used the possibility of Atlantis being located in the Azores as a backdrop to his 1936 thriller, They Found Atlantis.

Azaes, listed by Plato. This idea is supported by the linguist Dr Vamos-Toth Bator. However, a Portuguese correspondent has pointed out that the Azores is named after a goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) commonly found on the islands and portrayed on the regional flag. The renowned writer, Dennis Wheatley, used the possibility of Atlantis being located in the Azores as a backdrop to his 1936 thriller, They Found Atlantis.

In August 2013 Portuguese American Journal reported that the many pyramidal structures on Pico are clear evidence of extensive human activity in the archipelago long before the arrival of the Portuguese(o). A YouTube video(p) offers some interesting views of the pyramids.>If these pyramid builders were capable of sailing from mainland Europe as far as the Azores, understandably, it has prompted some to question whether the same people were able to complete the journey to the Americas! In 2014, Dominique Görlitz gave a lecture on the pyramids(ai) and the Atlantisforschung website has an article on the debate between Nuno Ribeiro and Portuguese archaeologists regarding the authenticity of the pyramids(aj).<

The following month the same journal announced the discovery of a pyramidal structure 60 metres high at a depth of 40 metres off the coast of the Azorean island of Terceira(i). Shortly afterwards the Portuguese Navy denied the existence of any such structure(j). Not exactly a surprise! Nevertheless, an Italian website has attempted to breathe new life into the story by linking this underwater pyramid report with pyramidal structures found on the island of Pico(k).

Atlantisforschung published an article that included critical comments about the ‘pyramid’ from both Greg Little and Andrew Collins.“A Portuguese Navy commander states that there is a read error of the sonar data and that the alleged pyramid was a volcanic mound. Afterwards, the Portuguese Hydrographic Institute [also] stated that the “ Pyramid ” was a known volcanic mound and posted actual underwater bottom contours of the site obtained from a hydrographic survey.

For the Portuguese Navy and its officials (who were originally said to be excited and involved), that was the end of the matter. But allegations arose almost immediately that this was a cover-up. Apparently, there was a Pyramid of Atlantis there, some claimed, and for obscure reasons, the government didn’t want anyone to know about it. At least that’s what is claimed. But of course, none of the people claiming a cover-up will ever go there and dive or lower a camera themselves. It’s probably [from their point of view; much better to keep it alive as a mystery. At the end of the day, no one wants to admit the truth — or know the truth.”(z).

The Wikiversity website has an extensive article(s) on the location of Atlantis, which is focused on the Azores and the bathymetric evidence for that archipelago having been a large single landmass at the end of the last Ice Age when sea levels were much lower. However, it is based on the literal acceptance of Plato’s 9,000 years before Solon for the date of the Atlantean War.

April 2018, saw British tabloid interest in Atlantis revived with further speculation on the Azores as the location of Plato’s submerged island(t). However, the details of the claim were rejected by Dr Richard Waller a lecturer at Keele University. Not content with recycling the old Azores theory, The Star also throws in the even more nonsensical idea of an Antarctican Atlantis.

A paper by Gerard Janssen of Leiden University places Homer’s Ogygia in the Azores(v).

In 2019, Fehmi Krasniqi published a three-and-a-half-hour video on the building of the Egyptian pyramids. For Krasniqi, the Ancient Black Egyptians travelled to the Americas and many other parts of the world(af). He claims that these ancient Egyptians travelled to America using Atlantis, now the Azores as a stepping-stone. This is offered as an explanation for the huge Olmec stone heads with African features!

A recent (2021) advocate of Atlantis in the region of the Azores is Victor Staner(w). In the same year, I was made aware of the work of Matthew Chinn who also pinpointed a location (38° 32′ 06″ N, 29° 24′ 09″ W) in the Azores region as the site of Atlantis, using satellite imagery and bathymetric data.

Support for the Azores continued with a book from Michael le Flem, Visions of Atlantis [1958] in 2022, an excerpt from which was published on the Ancient Origins website in January 2023(ah).

My leading questions regarding the proposed Azorean location for Atlantis are (a) why and (b) how would Atlanteans situated in the middle of the Atlantic launch an attack on Athens or Egypt that were over 4,200 km away? Unless those two questions are satisfactorily answered the Azores fails as the home of Atlantis.

(g) https://www.internalwaveatlas.com/Atlas2_PDF/IWAtlas2_Pg049_Azores.pdf

(h) https://www.andrewcollins.com/page/interactive/midatlan.htm

(i) https://portuguese-american-journal.com/terceira-subaquatic-pyramidal-shaped-structure-found-azores/

(j) https://www.unexplained-mysteries.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=255178&st=75

(k) https://www.stampalibera.com/?a=28020#sthash.EUkbmusn.dpuf

(l) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fRABMVIV0pQ

(m) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/02/160219134816.htm

(p) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wmd89nPH4WM

(q) https://www.scribd.com/document/327357287/Relatorio-Comissao (Portuguese)

(r) https://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/2171870-controversy-surrounds-artifacts-on-azores-islands-evidence-of-advanced-ancient-seafarers/

(u) https://www.amazon.com/New-Atlantis-Documentary-Historians-Speechless/dp/B07F2Z1272

(v) http://homerusodyssee.nl/id27.htm

(w) Atlantis | Captainvic (wixsite.com)

(z) Viking mice: Norse discovered Azores 700 years before Portuguese | CALS (cornell.edu)

(aa) Megalithic Constructions Discovered in the Azores, Portugal (scirp.org)

(ab) (57) Were the Azores home to an ancient civilisation? – BBC REEL – YouTube (Eng)

(ac) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBPyCYo97VQ (Port)

(ad) (99+) Dating the Cart-Ruts of Terceira Island, Azores, Portugal | Félix Rodrigues – Academia.edu

(af) Solving The Mystery Behind the Building of the Great Pyramid – Rising Tide Foundation

(ag) Was Atlantis in the Azores? – Klaus-Aschenbrenner (archive.org)

(ah) https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/azores-atlantis-0017844

Ogygia*

Ogygia is the home of Calypso, referred to by Homer in Book V of his Odyssey. It is accepted by some as an island in the Mediterranean that was destroyed by an earthquake before the Bronze Age. The Greek writers Euhemerus in the 4th century BC and Callimachus who flourished in the 3rd century BC, identified the Maltese archipelago as Ogygia. Others have more specifically named the Maltese island of Gozo as Ogygia. Anton Mifsud has pointed out[209] that Herodotus, Hesiod and Diodorus Siculus have all identified the Maltese Islands with Ogygia.

John Vella has added his support to the idea of a Maltese Ogygia in a paper published in the Athens Journal of History (Vol.3 Issue 1) in which he noted that “The conclusions that have emerged from this study are that Homer’s Ogygia is not an imaginary but a reference to and a record of ancient Gozo-Malta.”

Adding to the confusion, Aeschylus, the tragedian (523-456 BC) calls the Nile, Ogygian, and Eustathius, a Byzantine grammarian (1115-1195), claimed that Ogygia was the earliest name for Egypt(j).

Isaac Newton wrote a number of important works including The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended [1101], in which he discussed a range of mythological links to Atlantis, including a possible connection with Homer’s Ogygia. There is now evidence that he concurred(c) with the idea of a Maltese Ogygia in The Original of Monarchies(d).

Strabo referred to “Eleusis and Athens on the Triton River [in Boiotia]. These cities, it is said, were founded by Kekrops (Cecrops), when he ruled over Boiotia (Boeotia), then called Ogygia, but were later wiped out by inundations.”(i) However, Strabo also declared that Ogygia was to be found in the ‘World Ocean’ or Atlantic (j). To say the least, these two conflicting statements require explanation.

Richard Hennig opted for Madeira following the opinion of von Humboldt. Spanuth argued strongly against either Madeira or the Canaries[0017.149] and gave his support to the Azores as the most likely location of Calypso’s Island.. Not unexpectedly the Azores, in the mid-Atlantic, have also been nominated as Ogygia by other 20th century researchers such as Sykes(e) and Mertz[397]. In a 2019 paper(f), Gerard Janssen also placed Ogygia in the Azores, specifically naming the island of Saõ Miguel, which both Iman Wilkens [610.239] and Spanuth [015.226] also claimed. Spanuth added that until the 18th-century Saõ Miguel was known as umbilicus maris, which is equivalent to the Greek term, omphalos thallasses, used by Homer to describe Ogygia in chapter eight of the Odyssey!

Homer in his Odyssey identifies Ogygia as the home of Calypso. The Roman poet Catullus writing in the 1st century BC linked Ogygia with Calypso in Malta(g). However, Gozo’s claim is challenged by those supporting Gavdos in Crete(k). This opinion has been expounded more fully by Katerina Kopaka in a paper published in the journal Cretica Chronica(l), where her starting point is the claim that Gavdos had been previously known as Gozo! Another Greek claimant is Lipsi(o) in the Dodecanese. We must also add Mljet in Croatia to the list of contenders claiming(p) to have been the home of Calypso. Mljet is also competing with Malta as the place where St. Paul was shipwrecked!

>Further south is the beautiful Greek island of Othoni near Corfu where local tradition claims an association with Calypso. An article on the Greek Reporter website(r) suggests that “Evidence confirming this legend appears in the writings of Homer, who described a strong scent of cypress on Ogygia. Many cypress trees are grown on Othonoi.

Shortly after departing the island on a raft, Odysseus is shipwrecked on Scheria, which we know of today as Corfu. This implies that the two islands Homer described were relatively close. Likewise, the islands of Othonoi and Corfu are separated by a relatively short distance. Due to this mythological connection, during the 16th century, many naval maps described Othonoi as ‘Calypso island.‘”

Mifsud quotes another Roman of the same period, Albius Tibullus, who also identified Atlantis with Calypso. Other Maltese writers have seen all this as strong evidence for the existence of Atlantis in their region. Delisle de Sales considered Ogygia to be between Italy and Carthage, but opted for Sardinia as the remains of Calypso’s island.

Other researchers such as Geoffrey Ashe and Andrew Collins have opted for the Caribbean as the home of Ogygia. Another site supports Mesoamerica as the location of Ogygia, which the author believes can be equated with Atlantis(h). An even more extreme suggestion by Ed Ziomek places Ogygia in the Pacific(b)!

In the Calabria region of southern Italy lies Capo Collone (Cape of Columns). 18th-century maps(m) show two or more islands off the cape with one named Ogygia offering echoes of Homer’s tale. Respected atlases as late as 1860 continued to show a non-existent island there. It seems that these were added originally by Ortelius, inspired by Pseudo-Skylax and Pliny(n) . Additionally, there is a temple to Hera Lacinia at Capo Colonne, which is reputed to have been founded by Hercules!

By way of complete contrast, both Felice Vinci and John Esse Larsen have proposed that the Faeroe Islands included Ogygia. In the same region, Iceland was nominated by Gilbert Pillot as the location of Ogygia and Calypso’s home[742]. Ilias D. Mariolakos, a Greek professor of Geology also makes a strong case(a) for identifying Iceland with Ogygia based primarily on the writings of Plutarch. He also supports the idea of Minoans in North America.

A more recent suggestion has come from Manolis Koutlis[1617], who, after a forensic examination of various versions of Plutarch’s work, in both Latin and Greek, also placed Ogygia in North America, specifically on what is now the tiny island of St. Paul at the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada, a gulf that has also been proposed as the location of Atlantis.

Jean-Silvain Bailly also used the writings of Plutarch to sustain his theory of Ogygia, which he equated with Atlantis having an Arctic location[0926.2.299], specifically identifying Iceland as Ogygia/Atlantis with the islands of Greenland, Nova Zembla and Spitzbergen (Svalbard) as the three islands equally distant from it and each other.

The novelist Samuel Butler (1835-1902) identified Pantelleria as Calypso’s Island, but the idea received little support(q).

However, Ireland has been linked with Ogygia by mainly Irish writers. In the 17th century historian, Roderick O’Flaherty(1629-1718), wrote a history of Ireland entitled Ogygia[0495], while in the 19th century, Margaret Anne Cusack (1832-1899) also wrote a history in which she claimed[1342] a more explicit connection. This was followed in 1911 by a book[1343] by Marion McMurrough Mulhall in which she also quotes Plutarch to support the linking of Ireland and Ogygia. More recently, in The Origin of Culture[0217] Thomas Dietrich promotes the same view, but offers little hard evidence to support it.

>In 2023, an article on the Greek Reporter website renewed speculation regarding the possible identification of Ireland with Ogygia(s).<

This matter would appear to be far from a resolution.

[0495]+ http://archive.org/stream/ogygiaorchronolo02oflaiala/ogygiaorchronolo02oflaiala_djvu.txt

(a) https://greeceandworld.blogspot.ie/2013_08_01_archive.html

(b) https://www.flickr.com/photos/10749411@N03/5284413003/

(c) See: Archive 3439

(d) http://www.newtonproject.ox.ac.uk/view/texts/normalized/THEM00040

(e) ‘Where Calypso may have Lived’ (Atlantis, 5, 1953, pp 136-137)

(f)https://www.academia.edu/38535990/AT LANTIC_OGUGIA_AND_KALUPSO (Eng)

https://www.homerusodyssee.nl/id26.htm (Dutch)

(g) Lib. iv, Eleg. 1

(i) Strabo, Geography 9. 2. 18

(j) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ogygia

(k) https://gavdosgreece.page.tl

(m) https://nl.pinterest.com/pin/734438651719489108/

(n) See: Note 5 in Armin Wolf’s Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(o) http://www.wiw.gr/english/lipsi_niriedes/

(p) National Park The island of Mljet Croatia | Adriagate (archive.org) *

(q) https://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/snap-shots-samuel-butler-esq-1893-94

(r) https://greekreporter.com/2022/10/17/othonoi-island-westernmost-point-greece/

(s) https://greekreporter.com/2023/01/21/odysseus-travel-ireland/