Jacques R. Pauwels

Pauwels, Jacques R.

Jacques R. Pauwels, is a Belgian historian and a prolific writer, who touched on the subject of Atlantis in his book, Beneath the Dust of Time [1656]. In it he argued that Plato’s narrative was more than likely to have been inspired by the 2nd millennium BC eruption of Thera.

Jacques R. Pauwels, is a Belgian historian and a prolific writer, who touched on the subject of Atlantis in his book, Beneath the Dust of Time [1656]. In it he argued that Plato’s narrative was more than likely to have been inspired by the 2nd millennium BC eruption of Thera.

>He justified this opinion by supporting the more controversial claim that the Greek word ‘meizon‘ meaning ‘greater’, as used by Plato (Tim.24d-e), was a mistranscription of ‘meson’ meaning ‘between’. Therefore, according to Pauwels, the text should have described Atlantis as being between Libya and Asia rather than greater than Libya and Asia combined, arguably pointing to Minoan Thera as the location of Atlantis.

I must point out that, apart from the fact that the idea of a transcription error is purely speculative, the description is too vague as hundreds of Aegean islands could have been described at that time as lying between Libya and Asia.<

Meizon

Meizon is given the sole meaning of ‘greater’ in the respected Greek Lexicon of Liddell & Scott. Furthermore, in Bury’s translation of sections 20e -26a of Timaeus there are eleven instances of Plato using megas (great) meizon (greater) or megistos (greatest). In all cases, great or greatest is employed except just one, 24e, which uses the comparative meizon, which Bury translated as ‘larger’! J.Warren Wells concluded that Bury’s translation in this single instance is inconsistent with his other treatments of the word and it does not fit comfortably with the context[787.85]. This inconsistency is difficult to accept, so although meizon can have a secondary meaning of ‘larger’ it is quite reasonable to assume that the primary meaning of ‘greater’ was intended.

Jürgen Spanuth addressed this problem in Atlantis-The Mystery Unravelled [017.109] noting that “In other parts of the Atlantis report misunderstandings easily arose. Plato asserts that Atlantis was ‘larger’, ‘more extensive’ (meizon),than Libya and Asia Minor. The Greek word ‘meizon’ can mean both ‘larger in size’ and ‘more powerful.’ As the size of the Atlantean kingdom is given between two hundred and three hundred miles, whereas Asia Minor is considerably bigger, in this context the word ‘meizon’ should be translated not by ‘larger in size’ but by ‘more powerful’, which corresponds much better to the actual facts.”

In 2006, on a now-defunct website of his, Wells noted that “Greater can mean larger, but this meaning is by no means the only possible meaning here; his overall usage of the word may show he meant greater in some other way.”

It is also worth considering that Alexander the Great, (Aléxandros ho Mégas) was so-called, not because of his physical size, apparently, he was short of stature, but because he was a powerful leader.

The word has entered Atlantis debates in relation to its use in Timaeus 24e ’, where Plato describes Atlantis as ‘greater’ than Libya and Asia together and until recently has been most frequently interpreted to mean greater ‘in size’, an idea that I previously endorsed. However, some researchers have suggested that he intended to mean greater ‘in power’.

Other commentators do not seem to be fully aware that ‘Libya’ and ‘Asia’ had completely different meanings at the time of Plato. ‘Libya’ referred to part or all of North Africa, west of Egypt, while ‘Asia’ was sometimes applied to Lydia, a small kingdom in what is today Turkey. Incidentally, Plato’s statement also demonstrates that Atlantis could not have existed in either of these territories as ‘a part cannot be greater than the whole.’

A more radical, but less credible, interpretation of Plato’s use of ‘meizon’ came from the historian P.B.S. Andrews suggested that the quotation has been the result of a misreading of Solon’s notes. He maintained that the text should be read as ’midway between Libya and Asia’ since in the original Greek there is only a difference on one letter between the words for midway (meson) and larger than (meizon). This suggestion was supported by the classical scholar J.V. Luce and more recently on Marilyn Luongo‘s website(a), which is now closed.

Luongo attempted to link Mesopotamia with Atlantis, beginning with locating the ‘Pillars of Heracles‘ at the Strait of Hormuz and then using the highly controversial interpretation of ‘meizon‘ meaning ‘between’ rather than ‘greater’ she proceeded to argue that Mesopotamia is ‘between’ Asia and Libya and therefore is the home of Atlantis! She cited a paper by Andreea Haktanir to justify this interpretation of meizon(a).

This interpretation is quite interesting, particularly if the Lydian explanation of ‘Asia’ mentioned above is correct. Viewed from either Athens or Egypt we find that Crete is located ‘midway’ between Lydia and Libya.

Jacques R. Pauwels also supported Andrews’ controversial interpretation of Plato’s text (Tim.24d-e) in his 2010 book Beneath the Dust of Time [1656]. Therefore, he believes that the text should have described Atlantis as being between Libya and Asia rather than greater than Libya and Asia combined, arguably pointing to the Minoan Hypothesis.

As there are hundreds of islands ‘between’ Libya and Asia in the Aegean, this interpretation is very imprecise and useless as a geographical pointer.

In 2021, Diego Ratti, proposed in his new book Atletenu [1821], an Egyptian location for Atlantis, centred on the Hyksos capital, Avaris. In that context, he found it expedient to interpret ‘meizon’ in Tim. 24e & Crit.108e as meaning between Libya and Asia, which Avaris clearly is. I pressed Ratti on this interpretation and, after further study, he responded with a more detailed explanation for his conclusion(d). This is best read in conjunction with the book.

>>Some years ago, the late R. Cedric Leonard offered the following contribution to the meizon debate:

In Plato’s time (4th century B.C.) he would have written in large (all-capitals), continuous (no spaces between words), Athenian characters. The old Greek word meson would look like MESON in the Athenian script of Plato’s time. But mezon would look like MEION – the ancient Z closely resembled our modern capital letter I – the difference between the S and Z in the large Athenian script is obvious. (The Greek Z resembling our Roman Z is modern and does not apply to the older Attic scripts.)

But even in the later minuscule script the s and z in no wise resemble each other. A minuscule z (zeta) looks like ? while a medial s (sigma) looks like ? (absolutely nothing alike). The final backbreaker is that Plato included the same comparison in his Critias (108), in which his copyists would have to have made an identical mistake in that work as well. The odds are against the same identical mistake occuring in two separate works.(e) (see link for actual characters)<<

In relation to all this, Felice Vinci has explained that ancient mariners measured territory by the length of its coastal perimeter, a method that was in use up to the time of Columbus. This would imply that the island of Atlantis was relatively modest in extent – I would speculate somewhere between the size of Cyprus and Sardinia. An area of such an extent has never been known to have been destroyed by an earthquake.

Until the 21st century, it was thought by many that meizon must have referred to the physical size of Atlantis rather than its military power. However, having read a paper[750.173] delivered by Thorwald C. Franke at the 2008 Atlantis Conference, I was persuaded otherwise. His explanation is that “for Egyptians, the world of their ‘traditional’ enemies was divided in two: To the west, there were the Libyans, to the east there were the Asians. If an Egyptian scribe wanted to say, that an enemy was more dangerous than the ‘usual’ enemies, which was the case with the Sea Peoples’ invasion, then he would have most probably said, that this enemy was ‘more powerful than Libya and Asia put together’”.

This is a far more elegant and credible explanation than any reference to physical size, which forced researchers to seek lost continental-sized land masses and apparently justified the negativity of sceptics. Furthermore, it reinforces the Egyptian origin of the Atlantis story, demolishing any claim that Plato concocted the whole tale. If it had been invented by Plato he would probably have compared Atlantis to enemy territories nearer to home, such as the Persians.

This interpretation of meizon has now been ‘adopted’ by Frank Joseph in The Destruction of Atlantis[102.82], but without giving any due credit to Franke(b). No surprise there.!

(b) https://lost-origins.com/atlantis-no-lost-continent/ (offline Jan. 2018) See: Archive 2349

(c) https://web.archive.org/web/20070212101539/https://greekatlantis.com/

(d) More on Atlantis between Asia and Libya (archive.org)

(e) https://web.archive.org/web/20170113130726/http://www.atlantisquest.com/Plato.html *

Atlantic Ocean *

The Atlantic Ocean as defined by modern geography stretches between the Poles and is bounded on the west by the Americas and on the east by Europe and Africa. The word ocean is taken from the Greek ‘Okeanos’ which in turn has been suggested to have a Phoenician origin. Okeanos or ‘ocean river’ is first mentioned in Homer’s Iliad, a term that was employed by many ancient writers to refer to an ocean that they believed encircled the then-known world.

As a slight digression, I should mention that ‘Okeanos Potamos’ is an old name for the River Danube, a fact woven into Densusianu‘s theory of a Romanian Atlantis.

It seems that ‘Atlantic sea’ was a term first used by the poet Stesichorus (630-555 BC)(h), about two hundred years before Timaeus was composed by Plato and coinciding with the time of Solon’s famous visit to Egypt, to describe the seas beyond the Pillars of Heracles (Histories I. 202). If this is correct, then we must ask what term was used prior to Herodotus? If it was Okeanos, what body of water, if any, did the term ‘Atlantic’ apply to at the earlier period?. There have been suggestions that the word referred to the western Mediterranean.

Jacques R. Pauwels in his Beneath the Dust of Time[1656] maintains that contrary to popular belief “The Atlantic Ocean does not owe its name to these mountains, as we are often told; on the contrary, they received the name Atlas because they were situated near the Ocean and, like the Okeanos, conjured up the end of the (inhabited) world, the Oikoumene, and separated the earth from the heavens.”

George Sarantitis has proposed that the term used by Plato, Atlantikos Pelagos, can be more legitimately interpreted as ‘Atlantean archipelago’!(d)

However, some researchers, such as Alberto Arecchi(f), have asserted that the name was given to a very large inland sea in what is now North Africa bound by the Atlas Mountains. Jean Gattefosse was a leading exponent of this during the first half of the 20th century.Sarantitis has expanded on this idea, proposing(c) a vast network of huge inland lakes and waterways in what is now the Sahara, which has, in his view, allows a more acceptable interpretation of Hanno’s voyage. Others such as Diodorus (3.38), as late as the 3rd century BC, used the term ‘Atlantic’ to describe the Indian Ocean. It is quite clear that ancient geographical names did not always have the same meanings that they do today.

The confusion does not end there as some ancient writers have identified the Strait of Sicily as the location of the Pillars of Heracles and the waters of the Western Mediterranean as the Atlantic, with some identifying Tyrrhenia as being in the Atlantic.

Most important of all are the comments of Plato himself who refers to the Atlantic in Timaeus (24e) when Atlantis existed noting that ‘in those days the Atlantic was navigable’, implying that in his own time it was not. Consequently, he could not have been referring to the body of water that we know today as the Atlantic. Furthermore, Aristotle seemed to echo Plato when he wrote(e) that “outside the pillars of Heracles the sea is shallow owing to the mud, but calm, for it lies in a hollow.” This is not a description of the Atlantic that we know, which is not shallow, calm or lying in a hollow and which he also refers to as a sea not an ocean. So, what sea was he referring to?

Since other seas have been called Atlantic, we are therefore forced to consider possible alternatives that are also compatible with the other known features of Atlantis. The three leading candidates are

(i) the Western Mediterranean,

(ii) the Tyrrhenian Sea (which is part of the Western Mediterranean) and

(iii) the inland sea in North Africa, sometimes referred to as Lake Tritonis, favoured by Arecchi, Sarantitis and others.

I am personally inclined towards the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Pliny the Elder writing in the first century AD mentions a number of islands in what we now accept as the Atlantic Ocean. These include the Cassiterides (Britain), the Fortunate Isles (the Canaries), the Hesperides, the Gorgades and an island ‘off Mount Atlas’ named Atlantis. Understandably, Pliny’s comments have led to extensive controversy, particularly the identification of the island off Mount Atlas.

In fact, there is even some dispute about the location of the Mount Atlas in question, as there were a number of peaks known by that name in ancient times. Richard Hennig is cited by Zhirov[458.58] as describing the ‘utter confusion’ among ancient authors regarding the location of Mount Atlas.

Ignatius Donnelly was convinced that Atlantis had been situated in the Atlantic opposite the entrance to the Mediterranean. His theories predominated for over half a century and are still popular today. The late Gerry Forster, a British writer, has a 50-page paper supporting Donnelly’s contention posted on his website entitled The Lost Continent Rediscovered(a).

In order to add scientific credibility to Donnelly’s views the discovery of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge was offered as confirmation of the existence of Atlantis as parts of the ‘ridge’ would have been exposed when ocean levels were hundreds of feet lower during the last Ice Age. Today, the Canaries and the Azores are just remnants of what were once larger landmasses.

When Alfred Wegener advanced the theory of Continental Drift, later replaced by that of Plate Tectonics, was first presented, some atlantologists assumed that a mechanism for the disappearance of Atlantis in the Atlantic had been found. However, when the slow rate of movement was fully realised, the theory also sank as an explanation for the demise of Atlantis.

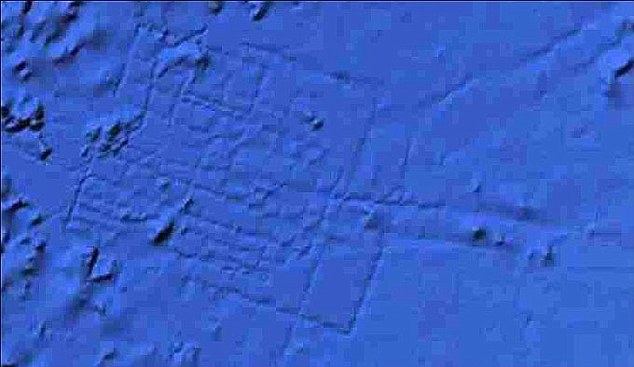

In April 2009 the media burst into one of its occasional ‘Atlantis found’ phases, when it was reported that evidence of an underwater city had been identified 600 miles west of the Canary Islands using Google Earth. The co-ordinates were given as 31 15’15.53N and 24 15’30.53W.

The site appeared to show a grid-like street system, which was estimated to be the size of Wales – a highly improbable, if not impossible size for a Bronze Age city. Apart from which, what appeared to be ‘streets’ would have been kilometers in width. Google responded with the following explanatory statement:

The site appeared to show a grid-like street system, which was estimated to be the size of Wales – a highly improbable, if not impossible size for a Bronze Age city. Apart from which, what appeared to be ‘streets’ would have been kilometers in width. Google responded with the following explanatory statement:

“what users are seeing is an artifact of the data collection process. Bathymetric (sea-floor) data is often collected from boats using sonar to take measurements of the sea-floor. The lines reflect the path of the boat as it gathers the data.” It did not take long before one commentator suggested that this statement was a cover-up.

By early February 2012, Google had corrected what they called ‘blunders’ contained in the original data, which in turn removed the anomalous image(b). No doubt conspiracy theorists will have their appetites whetted by this development.

Nine years later, on April 3, 2018(g), the UK’s Express regurgitated the same story!

As usual, people will believe what they want to believe.

(a) Wayback Machine (archive.org) *

(b) https://www.pcworld.com/article/249339/google_pulls_atlantis_from_google_earth.html

(c) The Peninsula of Libya and the Journey of Herodotus – Plato Project (archive.org)

(d) The Importance of Accurate Translation – Plato Project (archive.org)

(e) Meteorologica : Aristotle : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive 354a *

(f) https://www.liutprand.it/Atlantis.pdf

(h) https://www.loebclassics.com/view/stesichorus_i-fragments/1991/pb_LCL476.89.xml