Benjamin Jowett

Atlantic Sea

The Atlantic Sea is a geographical term, used by classical writers, such as Plato and Aristotle. In the context of Atlantis studies, it is not to be  confused with what we now know as the Atlantic Ocean. For the ancient Greeks ‘Okeanos’ was the name of a great river that flowed around the known world.

confused with what we now know as the Atlantic Ocean. For the ancient Greeks ‘Okeanos’ was the name of a great river that flowed around the known world.

>The valuable Theoi.com website notes(c) “In the ancient Greek cosmogony the RIVER OKEANOS (Oceanus) was a great, fresh-water stream which encircled the flat disc of the earth. It was the source of all of the earth’s fresh-water–from the rivers and springs which drew their waters from it through subterranean aquifers to the clouds which dipped below the horizon to collect their moisture from its stream.”<

Plato never referred to Atlantis as being located in the Atlantic Ocean, instead, he placed it in the Atlantic Sea. In a recent book [1895], Carlos Bisceglia made one simple but highly pertinent comment – “If Plato had thought that Atlantis was an island located in what we today call the Atlantic Ocean, he would have written that his Atlantis was ‘in the Middle of Okeanos’.”

The first English translation of the Atlantis texts by Thomas Taylor at the beginning of the 19th century correctly translated the word as ‘Sea’, however, after that, most English translations used ‘Ocean’ including the most widely available offering from Atlantis sceptic Benjamin Jowett.

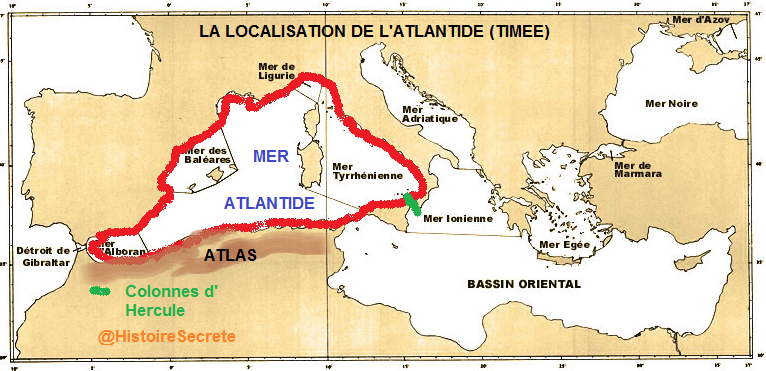

This claim of mistranslation is supported by Plato who noted that “in those days the Atlantic was navigable” (Tim. 24e), which clearly implies that in Plato’s time it was not. Additionally, Aristotle seemed to echo Plato when he wrote(a) that “outside the pillars of Heracles the sea is shallow owing to the mud, but calm, for it lies in a hollow.” This is not a description of the Atlantic that we know, which is not shallow, calm or lying in a hollow and which he also refers to as a sea, not an ocean. Both Plato and Aristotle seem to be describing a relatively small body of water. So, what sea were they referring to? The most popular suggestions so far are (1) The Western Basin of the Mediterranean, (2) The Tyrrhenian Sea or (3) The chotts of N.W. Africa.

Among others, Mário Saa a Portuguese writer identified the Western Mediterranean as Plato’s Atlantic Sea on a map in his book, Erridânia: geografia antiquíssima [1677]. A French website(b) supporting this identification has offered the map below. I also endorse this as a possible location for Plato’s Atlantic Sea in my book Joining the Dots.

(a) https://classics.mit.edu?Aristotle/meteorology.2.ii.html

(b) http://histoiresecrete.leforum.eu/t716-quelques-questions-se-poser-sur-le-Tim-e-Critias.htm (registration required)

(c) OCEANUS – Earth-Encircling River of Greek Mythology (theoi.com) *

Atlanticus

Atlanticus is the word used by Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa to describe Atlantis. Thomas Taylor in his celebrated translation of Plato’s works has subtitled Critias as Atlanticus. In the 20th century The Critias Atlanticus was published, being a compilation(a) of seven translations of Plato’s Critias that includes the work of Thomas Taylor, Benjamin Jowett, Henry Davis, R. G. Bury, Lewis Spence, W.R.M. Lamb, John Alexander Stewart.

Apulia, Izabol *

Izabol Apulia (1977- ) is a young dedicated hobbyist cartographer, who lives in Mesa, Arizona. She has developed a huge collection of maps(a), principally of Mediterranean islands, that depicts them at various stages between the Last Glacial Maximum and the present, showing how the rising sea levels gradually reduced them in size. She is highly critical of the sea level data developed and published by Kurt Lambeck and his team, preferring to use her own figures .

Apulia is also an inveterate blogger, using the name of ‘mapmistress’. She frequently published text to accompany individual maps that are often quite interesting. However, when she commented on Atlantis, in my opinion, she was seriously in error. Her big claim is that English translations of Plato’s text have been ‘botched’, in particular the work of Benjamin Jowett, whom she claims ‘invented’ the word Atlantis, which she further claims reads as ‘Atlas’ in the original text!

Not content with that, she places the Pillars of Heracles on Rhodes, with Atlantis to the north of that island in the Aegean.(b)

(a) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20180215195713/https://mapmistress.com/

(b) https://pseudoastro.wordpress.com/2009/02/01/planet-x-and-2012-the-pole-shift-geographic-spin-axis-explained-and-debunked/ (about half way down page)

(c) https://web.archive.org/web/20160624002531/https://mapmistress.blog.com/timescale/ or See Archive 2566 | (atlantipedia.ie) *

Andreas, Thomas (L)

Thomas Andreas is the compiler of a short e-book entitled The Truth about Atlantis: What Plato Really Said[932] which includes the translation of the Atlantis sections of Critias and Timaeus, by Benjamin Jowett as well as Jowett’s commentary on those passages. The book also includes a very brief ‘fact sheet’. This offering provides little additional information on the Atlantis question.

The Critias Atlanticus

The Critias Atlanticus is a compilation(a) of seven translations of Plato’s Critias that includes the work of Thomas Taylor, Benjamin Jowett, Henry Davis, R. G. Bury, Lewis Spence, W.R.M. Lamb, and John Alexander Stewart.

(a) https://www.hiddenmysteries.com/xcart/Critias-Atlanticus.html

Susemihl, Franz

Franz Susemihl (1826-1901) was a professor of classical philology at Greifswald University and later became rector there. He was renowned in academic circles for his translations of the works of Plato and Aristotle. His remarks on the Atlantis commentators of his day are as relevant today as over a century ago when he said “The catalogue of statements about Atlantis is a fairly good aid for the study of human madness.” The accuracy of his statement is borne out by the swollen ranks of today’s ‘lunatic fringe’ who claim inspiration from psychics, extraterrestrials or who insist that Atlantis was powered by crystals and possessed flying machines. The publication of such nonsense has continually undermined the credibility of serious Atlantology.

Franz Susemihl (1826-1901) was a professor of classical philology at Greifswald University and later became rector there. He was renowned in academic circles for his translations of the works of Plato and Aristotle. His remarks on the Atlantis commentators of his day are as relevant today as over a century ago when he said “The catalogue of statements about Atlantis is a fairly good aid for the study of human madness.” The accuracy of his statement is borne out by the swollen ranks of today’s ‘lunatic fringe’ who claim inspiration from psychics, extraterrestrials or who insist that Atlantis was powered by crystals and possessed flying machines. The publication of such nonsense has continually undermined the credibility of serious Atlantology.

*Susemihl’s German translation of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias is available online.(a)(b). Thorwald C. Franke has also included Susemihl’s translation along with that of Müller, Bury and Jowett and the Greek text of John Burnet[1492], all in a parallel format(c).*

It should be noted that Susemihl was an Atlantis sceptic.

(a) https://www.opera-platonis.de/Timaios.html

(b) https://www.opera-platonis.de/Kritias.html

*(c) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-timaeus-critias-synopsis.htm*

Shepard, Aaron (L)

Aaron Shepard is an American writer who published[857] the Atlantis related passages of Timaeus and Critias using the 19th century translation of Benjamin Jowett and entitled it The Atlantis Dialogue. In a short introduction, he expresses the view “that Atlantis was an invention designed to help illustrate his (Plato’s) philosophy” and should be treated as just an allegorical tale.

Sable vestments

‘Sable vestments’ is Robert Bury’s and W.R.M. Lamb‘s translation of the Greek kuanon stolen in Critias 120b which describes the ceremonies of the Atlantean rulers when they meet. At first sight it appeared to me that this might be a reference to a need for fur robes implying a cold northern climate, compatible with the habitat of the sable.

Atlantean rulers when they meet. At first sight it appeared to me that this might be a reference to a need for fur robes implying a cold northern climate, compatible with the habitat of the sable.

Anton Mifsud advised me that the Greek text more correctly translates as ‘dark-blue garments’ confirming both Jowett and Thomas Taylor, who translate kuanos as ‘azure’. Other translations on offer are ‘dark blue‘ (Lee), ‘steel blue‘ (Wells) and ‘purple‘ (David Horan). It is more commonly referred to nowadays as ‘Tyrian purple’.

>Into this mix we must throw the fact that the ancient Greeks had no word for ‘blue’. They were not alone as “There isn’t a single term for “blue” in Russian. The two phrases “galoboy” and “sini,” which are typically translated as “light blue” and “dark blue,” are used instead. Nevertheless, for Russians, these words refer to two entirely distinct colors rather than two variations of the same color.”(a)<

If this reference to azure robes was actually recounted to Solon, and not just a Platonic embellishment, it places Atlantis in the 2nd millennium BC, which was when the earliest reference to the production of ‘Tyrian dye’ by the Phoenicians is recorded (See: Murex). The use of purple and indigo clothing was a fashion statement by the political and religious elite that lasted for at least three millennia, which can be seen on the coronation portrait of Britain’s King George VI.

English Translations (L)

English Translations of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias have been freely available since 1793 when Thomas Taylor produced his translation.

In 1804 Taylor published the first English translation of the entire Platonic corpus. In 1871, Benjamin Jowett produced the most commonly quoted version of the Atlantis Dialogues, principally because his work is now out of copyright. Henry Davis produced a translation of Critias in the 19th century and John Alexander Stewart also offered a translation of Critias early in the 20th century.

1925 saw W.R.M. Lamb publish a translation of some of Plato’s works and today his rendering of both Timaeus and Critias is used by the Perseus Digital Library(a). In 1929, Lewis Spence included a composite version of the Atlantis texts in The History of Atlantis, using the English translations of Jowett and Archer-Hind for Timaeus and the French translations of Jolibois and Negris for Critias. Rev. R. G. Bury gave us what was arguably the best translation of the Dialogues (Loeb Classical Library, 1929) and is included at the beginning of this book. Francis M. Cornford (1874-1943) published his Timaeus (Bobbs-Merrill, 1937)

Sir Desmond Lee produced a new English translation in 1972 (Penguin)

Professor Diskin Clay delivered an acclaimed translation of Critias (Hackett Publishing, 1997). Professor Donald J. Zeyl offered a new translation of Timaeus (Hackett Publishing, 2000). Dr. Peter Kalkavage published a highly regarded translation of Timaeus (Focus Philosophical Library, 2001).

In 2008, Robin Waterfield offered a new translation of Critias and Timaeus[0922] as well as a revision of Desmond Lee’s translation of them by Thomas Kjeller Johansen.

Spence, Lewis*

James Lewis Thomas Chalmers Spence (1874-1955) attended Edinburgh University, after which he began a career in journalism that included a stint as sub-editor of The Scotsman. His book publishing began in 1908 with the first English translation of the sacred Mayan book Popul Vuh [257], followed by A  Dictionary of Mythology, so eventually, he had over forty works to his name. He was a keen Scottish Nationalist and stood for parliament in 1929. He was a founder member of the political movement that later evolved into today’s Scottish National Party (SNP).

Dictionary of Mythology, so eventually, he had over forty works to his name. He was a keen Scottish Nationalist and stood for parliament in 1929. He was a founder member of the political movement that later evolved into today’s Scottish National Party (SNP).

Among his literary output, which included mythology, occultism and poetry, were five books relating to Atlantis [256,258,259,260 262]. In 1932 he was editor of the Atlantis Quarterly magazine. He corresponded with Percy Fawcett and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, advising the latter on the subject of Atlantis preceding the writing of The Maracot Deep and recently republished as Atlantis – Discovering the Lost City [235], another example of cynical publishing!

Spence at one point became the Chosen Chief of British Druidism and there is a claim that he was a member of at least one continental Rosicrucian organisation, although this report may be the result of confusion with H. Spencer Lewis, an American Rosicrucian. In 1941 he wrote [261] about the occult and the war, then raging in Europe. In that book he argued that the war was the result of a satanic conspiracy centred in Munich and the Baltic States. The following year he wrote [262] of his view that Atlantis had been destroyed as a form of divine retribution and that Europe was in danger of a similar fate.

His books were very popular with the general public but scorned by the scientific establishment, whom Spence mockingly referred to as “The Tape Measure School”. In truth his theories relating to Atlantis were highly speculative and often based on rather tenuous links. Spence believed that Atlantis was situated in the Atlantic and linked by a land bridge with the Yucatan Peninsula and that after the destruction of Atlantis, 13,000 years ago, the Atlantean refugees fled across this landbridge and are now recognised as the ancient Maya. A recent website(d) supports the idea of a landbridge from Cuba to the Yucatan Peninsula.

Spence believed that the ancient traditions of Britain and Ireland contain memories of Atlantis. An article of his on the subject can be found on the Internet.

In The Problem of Atlantis [258.205] Spence quoted a report that allegedly came from the Western Union Telegraph Company, which claimed that while searching in the Atlantic for a lost cable in 1923 that when taking soundings at the exact same spot where it had been laid twenty-five years before they found that the ocean bed had risen nearly two and a quarter miles. The account was quoted widely; however, not long afterwards, Robert B. Stacy-Judd made direct enquiries of his own to Western Union and the U.S. Navy, who denied knowledge of any such report[607.47]! It would be interesting to know the source of this ‘fake news’.

Spence’s The History of Atlantis [259] can now be downloaded or read online(c). In this book Spence offers his own composite translation of the Atlantis texts based on the English and French translations of Jowett, Archer-Hind, Jolibois and Negris.

A 2005 edition of the book from Barnes & Noble has an introduction by Professor Trevor Palmer.

Sprague de Camp in his Lost Continents [194] chose Spence as one of “the few sane and sober writers on the subject” of Atlantis and then proceeded to debunk much of what Spence wrote. [p.95].

It appears that among others, Spence’s work inspired the backdrop to a number of works by the pulp fiction writer, Robert E. Howard(e), who is perhaps best known as the creator of Conan the Barbarian.

(c) https://www.archive.org/details/historyofatlanti00spenuoft