Sprague de Camp

Houvellique, M. L.

Caspian Sea *

The Caspian Sea is not usually associated with the story of Atlantis, but as early as the 19th century Moreau de Jonnès proposed the Sea of Azov as the location of Atlantis and that the Black, Caspian and Aral Seas were just remnants of a large ocean.

In the 1920s, Reginald Fessenden promoted a similar idea [1012], supporting it with some evidence that the Caspian and Aral seas were still connected as late as 200 BC.

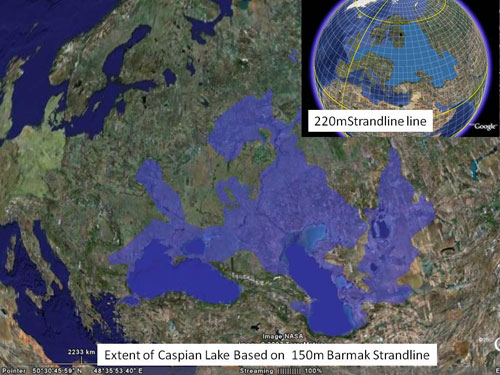

While this may sound like a wild idea, one modern researcher, Ronnie Gallagher, has written an important paper(b) supporting the concept (see fig.8).

Gallagher has suggested that, based on whichever data is used this enlarged body of water had been joined with the Black Sea/Mediterranean or spread even further north as far as the Arctic. His conclusions are mainly based on sets of strandlines identified at elevations of 150 and 220 metres above sea level in the region of the Caspian Sea(d). From these he extrapolated an enormous inland lake centred on the Caspian (150m) or if the 220m level is used it was a sea joined to the Arctic Sea in the North. Gallagher published a hypothetical Eurasian flood map based on these figures. However, it should be noted that Professor E. N. Badyukova has offered some critical comments regarding Gallagher’s claims(e).

In the 1950s, Sprague De Camp wrote [0194.88] of compliant scientists in Stalinist Russia claiming that Atlantis had existed on land now covered by the Caspian Sea.

Fessenden cites Strabo (Book 11:7;43), who recounts a tradition that the Caspian had been connected with the Black Sea by way of the Sea of Azov.

Modern proponents of Atlantis in the Sea of Azov have suggested(a) that at the end of the last Ice Age  floods of meltwater poured into the Caspian Sea, which in turn escaped through the Manych-Kerch Gateway(c) into what is now the Sea of Azov, but at that time contained the Plain of Atlantis!

floods of meltwater poured into the Caspian Sea, which in turn escaped through the Manych-Kerch Gateway(c) into what is now the Sea of Azov, but at that time contained the Plain of Atlantis!

Immediately to the south of the Caspian are the Caucasus Mountains which have also had links with Atlantis proposed.

(a) https://atlantis-today.com

(b) Wayback Machine (archive.org) *

Tournefort, Joseph Pitton de

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) sometimes referred to as “the Father of Botany”, strayed from his chosen field when he suggested that Atlantis had been located  in the Atlantic and that following an earthquake in the Mediterranean, the level of that sea rose causing an outflow into the Atlantic that swamped Atlantis. Sprague de Camp states that Tournefort got his idea from the Greek writer Strato of Lampsacus (c. 250 BC), who declared that the Black Sea had joined the Mediterranean when it overflowed into it and in a similar fashion the Mediterranean had joined the Atlantic.

in the Atlantic and that following an earthquake in the Mediterranean, the level of that sea rose causing an outflow into the Atlantic that swamped Atlantis. Sprague de Camp states that Tournefort got his idea from the Greek writer Strato of Lampsacus (c. 250 BC), who declared that the Black Sea had joined the Mediterranean when it overflowed into it and in a similar fashion the Mediterranean had joined the Atlantic.

Stel Pavlou (Atlantipedia.com) has traced Tournefort’s comments to the posthumously published Relation d’un voyage du Levant[1467] published in sets of two and three volumes. Kessinger has published a facsimile copy of volume 3 and the original French can also be read or downloaded from the Internet(a). An English translation was reportedly published in 1718.

Spence, Lewis*

James Lewis Thomas Chalmers Spence (1874-1955) attended Edinburgh University, after which he began a career in journalism that included a stint as sub-editor of The Scotsman. His book publishing began in 1908 with the first English translation of the sacred Mayan book Popul Vuh [257], followed by A  Dictionary of Mythology, so eventually, he had over forty works to his name. He was a keen Scottish Nationalist and stood for parliament in 1929. He was a founder member of the political movement that later evolved into today’s Scottish National Party (SNP).

Dictionary of Mythology, so eventually, he had over forty works to his name. He was a keen Scottish Nationalist and stood for parliament in 1929. He was a founder member of the political movement that later evolved into today’s Scottish National Party (SNP).

Among his literary output, which included mythology, occultism and poetry, were five books relating to Atlantis [256,258,259,260 262]. In 1932 he was editor of the Atlantis Quarterly magazine. He corresponded with Percy Fawcett and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, advising the latter on the subject of Atlantis preceding the writing of The Maracot Deep and recently republished as Atlantis – Discovering the Lost City [235], another example of cynical publishing!

Spence at one point became the Chosen Chief of British Druidism and there is a claim that he was a member of at least one continental Rosicrucian organisation, although this report may be the result of confusion with H. Spencer Lewis, an American Rosicrucian. In 1941 he wrote [261] about the occult and the war, then raging in Europe. In that book he argued that the war was the result of a satanic conspiracy centred in Munich and the Baltic States. The following year he wrote [262] of his view that Atlantis had been destroyed as a form of divine retribution and that Europe was in danger of a similar fate.

His books were very popular with the general public but scorned by the scientific establishment, whom Spence mockingly referred to as “The Tape Measure School”. In truth his theories relating to Atlantis were highly speculative and often based on rather tenuous links. Spence believed that Atlantis was situated in the Atlantic and linked by a land bridge with the Yucatan Peninsula and that after the destruction of Atlantis, 13,000 years ago, the Atlantean refugees fled across this landbridge and are now recognised as the ancient Maya. A recent website(d) supports the idea of a landbridge from Cuba to the Yucatan Peninsula.

Spence believed that the ancient traditions of Britain and Ireland contain memories of Atlantis. An article of his on the subject can be found on the Internet.

In The Problem of Atlantis [258.205] Spence quoted a report that allegedly came from the Western Union Telegraph Company, which claimed that while searching in the Atlantic for a lost cable in 1923 that when taking soundings at the exact same spot where it had been laid twenty-five years before they found that the ocean bed had risen nearly two and a quarter miles. The account was quoted widely; however, not long afterwards, Robert B. Stacy-Judd made direct enquiries of his own to Western Union and the U.S. Navy, who denied knowledge of any such report[607.47]! It would be interesting to know the source of this ‘fake news’.

Spence’s The History of Atlantis [259] can now be downloaded or read online(c). In this book Spence offers his own composite translation of the Atlantis texts based on the English and French translations of Jowett, Archer-Hind, Jolibois and Negris.

A 2005 edition of the book from Barnes & Noble has an introduction by Professor Trevor Palmer.

Sprague de Camp in his Lost Continents [194] chose Spence as one of “the few sane and sober writers on the subject” of Atlantis and then proceeded to debunk much of what Spence wrote. [p.95].

It appears that among others, Spence’s work inspired the backdrop to a number of works by the pulp fiction writer, Robert E. Howard(e), who is perhaps best known as the creator of Conan the Barbarian.

(c) https://www.archive.org/details/historyofatlanti00spenuoft

Silbermann, Otto

Otto Silbermann was an investigator who, in 1930, published a short work[548] on the existence of Atlantis.>Sprague de Camp commenting on Silbermann’s Atlantis theories described them as “the most plausible African interpretation of Atlantis.”<

He covers all the principal theories of his day and finishes off with his conclusion that the Atlantis story had been based on a Phoenician record of a war between Egypt and Libya that had been fought in the Chott region around 2540 BC. He argued that a story such as the Atlantis tale could not have survived oral transmission with all the details recorded by Plato for 9,000 years. I must say that I consider this an extremely valid opinion. Nevertheless, a 2015 report from Reid & Nunn highlighted the ability of Australian aborigines to transmit faithfully, a record of events over even greater timespans.(a)

Although Silbermann appears to have been German, he published his book in French and apparently planned a second publication with the title of A Discovered Continent: The History of a Libyan-Phoenician Atlantis, of which I can find no trace.

(a) https://www.academia.edu/16307214/Indigenous_Australian_Stories_and_Sea-Level_Change

Chain of Transmission

The Chain of Transmissionof Plato’s tale to us today should be borne in mind when applying any interpretation to elements in the text available to us. We have absolutely no idea how many languages had to carry the story before it was inscribed on their ‘registers’ (Jowett) in Sais, assuming that aspect of the story to be true. The Egyptian priests translated this tale from the pillars for Solon, who then related the story to his friend Dropides who passed it on to his son the elder Critias who, at the age of ninety conveys it to his grandson, the younger Critias, aged nine. Critias then conveyed the tale to his nephew Plato. Platothen composed his Timaeus and Critias dialogues, which eventually reached us through a rather circuitous route.

There are a number of versions of Plato’s family tree, Sprague de Camp records[194.324] three from ancient sources, Diogenes Laërtius, Iamblichus & Proclus, which have small variations. Some sceptics have sought to undermine the credibility of the Atlantis story by highlighting these differences and/or questioning whether the persons recorded by Plato adequately span the years between Solon and Plato. Some of the controversies stem from a number of family members, historical figures of that era and participants in the dialogues who share the same name.On the other hand, I would argue if the Atlantis narrative was just a concoction, I would expect Plato to also have invented a more watertight pedigree.

Plato’s original writings were essentially lost to Western civilisation but for the efforts of Muslim scholars who preserved them until they eventually emerged in Western Europe during the Middle Ages, after they were brought from Constantinople in the century before its fall. In due course the texts were translated into Latin from those Greek versions, which are now lost.

Wilhelm Brandenstein suggested that Solon had combined two accounts, one from Egypt relating to the Sea Peoples and the other concerned a conflict between Athens and Crete(c). However, this is not convincing as it conflicts with too many other details in Plato’s narrative.

Wikipedia notes that ‘the scholastic philosophers of the Middle Ages did not have access to the works of Plato – nor the Greek to read them.’ Today there are only seven manuscripts of Plato’s work extant, the earliest of which dates to around 900 AD. It is unfortunate that the earliest versions of Plato’s work available to us are only Latin translations of the original Greek text.

Chalcidius undertook the first translation of Timaeus from Greek to Latin in the 3rd century AD. He translated the first 70% of the text from earlier Greek versions, now lost. The earliest translation of Plato’s complete works into Latin was by Marsilio Ficinoin the late 15th century. Janus Cornarius provided us with a Latin translation from earlier Greek sources, apparently different from those used by Ficino. A comparison of the partial Chalcidius and complete Ficino translations shows considerable divergences. The Ficino Latin text was in turn translated back into Greek at the Aldina Academy in Venice in the 16th century.

In chapter two of his History of Atlantis Lewis Spence has produced a version of the Atlantis texts that is an amalgam of various earlier translations ‘acceptable’ to him.

Diaz-Montexano has written, in his distinctive poor English, a short criticism(a) of the quality of medieval translations of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias that are the basis of the vernacular versions available today.

There are legitimate questions that can be raised regarding the accuracy of the text used by researchers and since some theories relating to Atlantis are often dependant on the precise meaning of particular words, this lack of an original text, leaves some doubt over the persuasiveness of individual hypotheses. It is highly improbable that current texts do not contain a variety of errors when we consider the number of links in the chain of transmission.

Many quotations from Plato’s text will have alphanumeric references, which are derived from the earliest printed edition of Plato’s works by the 16th century French scholar and printer, Henricus Stephanus; these show page numbers and the letters A-E at equal distances down each page. Although they bear no relationship to the natural breaks in the narrative, the majority of editions and translations now include them.

The entirety of Plato’s Dialogues is to be found on many sites on the Internet. However, I can highly recommend the Perseus website(b) where the works of most ancient authors can be found there in both English and their original languages. It has a number of valuable search tools for both the novice and seasoned student of Atlantology.

(b) https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/

(c) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_brandenstein_engl.htm

Carthage

Carthage is today a suburb of the North African city of Tunis.

Al Barone wrote(k) that it “was founded by Phoenician settlers from the city of Tyre, who brought with them the city-god Melqart. Philistos of Syracuse dates the founding of Carthage to c. 1215 BC, while the Roman historian Appian dates the founding 50 years prior to the Trojan War (i.e. between 1244 and 1234 BC, according to the chronology of Eratosthenes). The Roman poet Virgil imagines that the city’s founding coincides with the end of the Trojan War. However, it is most likely that the city was founded sometime between 846 and 813 BC.“

Gerard Gertoux argues(h) that recent discoveries push this date back to at least 870 BC, if not further. Prior to that, the Roman poet, Silius Italicus (100-200 AD), tells us that according to legend the land there had been occupied by Pelasgians(e).

South of Carthage, in modern Tunisia, there are fertile plains that were the breadbasket of Rome and even today can produce two crops a year, despite a much-disimproved climate.

In 500 BC Hanno, the Navigator was dispatched from Carthage with the intention of establishing new African colonies. Around a century later another Carthaginian voyager, Himilco, is also thought to have travelled northward(f) in the Atlantic and possibly reached Ireland, referred to as ‘isola sacra’. Christopher Jones has claimed on his website(d) that Himilco reached Britain and Ireland in the 5th century BC.

Cecil Torr (1857-1928) the British antiquarian and author published a paper in 1891 entitled The Harbours of Carthage(j) in which he suggested that the layout of Carthage may have inspired some of Plato’s descriptions of Atlantis. However, we are now aware that some of these features did not exist until after Plato’s time.

>Sometime later Victor Bérard, pointed out[0160] the similarity of Carthage with Plato’s description of Atlantis. The prominent Atlantis sceptic Sprague de Camp at least complimented Bérard that his theory was ” more difficult to eliminate ” than those of other researchers and authors. After all, de Camp concedes that Carthage was ” in the right direction from the point of view of Greece “, which cannot be said of Crete, for example. Atlantisforschung discusses at some length de Camp’s view of Bérard’s Atlantean Carthage theory(I).<

Frank Joseph followed Lewis Spence in suggesting that Carthage may have been built on the remains of an earlier city that had been Atlantis or one of her colonies. In like manner, when the Romans destroyed Carthage after the Punic Wars, they built a new Carthage on the ruins, which became the second-largest city in the Western Empire.

The circular lay out of the city with a central Acropolis on Byrsa hill, surrounded by a plain with an extensive irrigation system, has prompted a number of other authors, including Massimo Pallotino[222] and C. Corbato[223] to suggest that it had been the model for Plato’s description of Atlantis. This idea has now been adopted by Luana Monte(c).

out of the city with a central Acropolis on Byrsa hill, surrounded by a plain with an extensive irrigation system, has prompted a number of other authors, including Massimo Pallotino[222] and C. Corbato[223] to suggest that it had been the model for Plato’s description of Atlantis. This idea has now been adopted by Luana Monte(c).

Andis Kaulins has suggested that “ancient Tartessus (which was written in Phoenician as Kart-hadasht) could have been the predecessor city to Carthage on the other side of the Strait of Sicily. Plato reported that Tartessus was at the Pillars of Herakles.”(a) Kaulins places the ‘Pillars’ somewhere between the ‘toe of Italy’ and Tunisia.

Richard Miles has written a well-received history[1540] of Carthage, a task hampered by the fact that the Carthaginian libraries were destroyed or dispersed after the fall of the city, perhaps with the exception of Mago’s agricultural treatise, which was translated into Latin and Greek and widely quoted.

Delisle de Sales placed the Pillars of Heracles in the Gulf of Tunis.

A book-length PhD thesis by Sean Rainey on Carthaginian imperialism and trade is available online(b).

(a) Pillars of Heracles – Alternative Location (archive.org)

(b) https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/4354

(c) ARTICOLO: Cartagine come Atlantide? (archive.org)

(d) https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2011/12/13/high-north-carthaginian-exploration-of-ireland/

(f) http://phoenicia.org/himilco.html

(h) https://www.academia.edu/2421053/Dating_the_foundation_of_Carthage?email_work_card=view-paper

(i) Atlantis Rising magazine #39 p69 http://pdfarchive.info/index.php?pages/At

(j) The Classical Review. 5 (6): 280–284. June 1891

(k) https://www.academia.edu/5333030/The_Amazingh_Warriors_of_Amazon_and_Carthage

(l) Atlantis in Karthago – Die Lokalisierung des Victor Bérard – Atlantisforschung.de (German) *

Brazil

Brazil was arguably (re)discovered by the Pinzon brothers, before Columbus first reached the West Indies according to Steven Sora(g). However, it is more generally accepted, particularly by Brazilians, that the Portuguese navigator Pedro Alvares Cabral was the first European to discover Brazil in 1500.

Brazil has had few serious investigators propose it as the location of Atlantis. Although, in 1947 Harold T. Wilkins claimed[0363.97] that Quetzalcoatl was from Atlantean Brazil. Earlier in the 20th century, Col. P.H. Fawcett, the famous explorer, disappeared while searching in the Brazilian rain forest for a ‘lost city’ that he called ‘Z’. A 2009 book by David Grann about Fawcett’s searches in Brazil, entitled The Lost City of Z [0772] was the basis for a film released in 2016. Sprague de Camp listed[0194.329] a George Lynch supporting a Brazilian Atlantis in 1925. In fact, Lynch was a fund-raiser for Fawcett. However, the Atlantisforschung website is adamant that there is no evidence that Lynch favoured Brazil as the location of Atlantis(i)!

However, although there is growing evidence of ancient roads, plazas and bridges in Brazil’s vast tropical forests, further data is needed before we can attempt to fit these structures into any specific culture or chronology.

An article(e) in the August 2017 edition of Antiquity offers evidence that humans lived in Brazil more than 20,000 years ago, which is many millennia before the Clovis people arrived in North America.Americo Huari Román is a Peruvian electrical engineer who was born in the former Inca capital of Cuzco. He is the author of La Atlantida y el Imperio de los Incas (Atlantis and the Empire of the Incas) [1448]. Before the Great Deluge, Huari claims that most of central Brazil had been a huge inland sea and that Atlanteans and Arawacs lived around this lake and that the one artefact left by them is the enormous carved Ingá Stone(j).

The possibility of Phoenician contact with Brazil has a number of supporters and a range of websites supports this controversial view(a). One such advocate, Ronald Barney, maintains[1185] that they concentrated their influence in the northeastern region of the country citing the work of Ludwig Schwennhagen[1550] and Apollinaire Frot(f).

There would appear to be evidence for 3rd century AD Roman contact with Brazil(h). The 1982 discovery of Roman amphorae in a shipwreck in Guanabara Bay near Rio de Janeiro, 15 miles offshore in 100 feet of water. This was badly received locally as it dispensed with the claim for Pedro Alvares Cabral having been the first European to land in Brazil(k)(l). The large number of amphorae found in the wreck would seem to indicate that their cargo had not been offloaded and as it was located 15 miles offshore, we have no reason to think that the ship ever reached land. I would speculate that the Guanabara wreck was simply blown of course while on a trading mission.

Whether other Roman vessels reached America with greater success is a more contentious matter. A variety of Roman artifacts have been discovered since the early nineteenth century, at various locations in America, inciting what was often furious debate(m)(n)(o). If the Romans had established links with the Americas, I find it hard to accept that they would not have broadcast the fact, if only to inflate their imperial ego!

May 2013 saw a flurry of media interest when a Japanese submersible found evidence in the form of granite suggesting of a previously unknown continental mass that sank about 900 miles off the coast of Rio de Janeiro. Members of the expedition have played down any attempt to link this discovery with Atlantis(b)(c).

May 2013 saw a flurry of media interest when a Japanese submersible found evidence in the form of granite suggesting of a previously unknown continental mass that sank about 900 miles off the coast of Rio de Janeiro. Members of the expedition have played down any attempt to link this discovery with Atlantis(b)(c).

This reminiscent of the reaction in 1931 when two islands were reported to have emerged from the sea off Brazil and within a short time, claims that they were a returning Atlantis were widely quoted(d).

Any suggestion that the land of Hy-Brasil in Irish mythology has any connection with Brazil or Atlantis is just wild speculation.

(a) https://phoenicia.org/brazil.html

(c) https://www.counselheal.com/articles/5276/20130507/scientists-found-atlantis-coast-brazil.htm

(d) https://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/98134066?searchTerm=Atlantis&searchLimits=

(e) https://www.sciencenews.org/blog/science-ticker/stone-age-people-brazil-20000-years-ago

(g) See: Archive 3480

(h) The Mysterious Ancient Underwater Roman Relics of Brazil | Mysterious Universe (archive.org) *

(i) George Lynch – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(l) ‘Roman’ jars found in Guanabara Bay could re-write Brazil’s history | indy100

(m) Did Ancient Romans Reach The Americas Long Before Columbus? – Ancient Pages

(n) An Expert Doubts Roman Coins Found in U.S. Are Sea?Link Clue – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

(o) Mysterious jars found in Brazil offer world-changing version of history (msn.com) *

Braghine, Col. Alexander Pavlovitch *

Col. Alexander Pavlovitch Braghine (1878-1942) is well known for his book[156]+ on Atlantis, which he considers to have been the original homeland of many of the tribes of South America. He attributes the destruction of Atlantis to the consequences of at least one close encounter between Earth and Halley’s Comet, during the Holocene period, on 7th June 4015 BC. He maintains that this intrusion upset the orbits of Earth and Venus causing worldwide destruction. Many of Braghine’s catastrophist ideas are to be found in Immanuel Velikovsky’s later books without any reference to him. Braghine on the other hand was quite willing to acknowledge any use by him of other writers’ work. Some have explained Velikovsky’s omission as being the result of perceived racism on the part of Braghine.

Braghine in his The Shadow of Atlantis mentions a tribe of white-skinned ‘Indians’ called Paria in a region of Venezuela called Atlan. He claims that their legends refer to them having an original homeland beyond the ocean that had been destroyed in a terrible cataclysm. However, I have been unable to find any other reference to this tribe apart from that of Frank Joseph[104] who locates it in the Apure region between the Orinoco River and its tributary, the Apure. Braghine’s work was also published in French[157]. A few years earlier Richard O. Marsh published White Indians of Darien [1551]+ in which he recounted his meeting with ‘white Indians’ in the remote jungles of Panama. However, claims of encounters with white Indians in Amazonia go back as far as the 16th century(a). When I saw some old photos(b) of these ‘white’ children, I was immediately struck by the fact that many were squinting and appeared to be suffering from albinism, although this has been denied(c).

Sprague de Camp lists[194] a series of errors in Braghine’s book, finishing with the ominous remark that ‘you believe Colonel Braghine at your peril.’

However, David Hatcher Childress does not shrink from correcting[620.270] the mistakes made by deCamp in his critical attack.

Your compiler found Braghine’s book interesting and informative, although rather dated as it is now (2022) over eighty years old. I could find no justification for deCamp’s condemnation of Braghine’s work.

[156]+ https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015002694399;view=1up;seq=12

[1551]+ https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015010699448&view=1up&seq=7&skin=2021

(a) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Amazonian_Indians

(c) https://fdocuments.net/document/white-indians-of-darien.html?page=2 (link broken) *

Atalanta

Atalanta was a relatively insignificant island that according to Thucydides (II, 32) was “lying off the coast of Opuntian Locris”. The Athenians built a fort there in 431 BC and following an earthquake it suffered an inundation that caused serious loss of life and destruction of property (III, ChapXI par.89). The island is known today as Talandonisi. In this same area, North West of Athens, we have still the town of Atalanti and the Bay of Atalanti.

This report of the flooding of Atalanta is sometimes taken out of context by some supporters of Plato’s Atlantis and presented as a clear reference to it. This superficial interpretation does not stand up to scrutiny in terms of date, location, size, nor importance.

This report of the flooding of Atalanta is sometimes taken out of context by some supporters of Plato’s Atlantis and presented as a clear reference to it. This superficial interpretation does not stand up to scrutiny in terms of date, location, size, nor importance.

Others, such as Sprague de Camp, maintain that Plato’s Atlantis is pure fiction inspired by the destruction of Atalanta ‘in a single day’ by a flood following an earthquake. However, it would appear foolish to concoct a story such as that of Atlantis and base it on an inconsequential island, located only 50 miles from Athens, with a similar name, destroyed a few years previously and still expect it to be believed as true.

*Others claim that the sudden flooding of Tiryns (Zangger) or Helike prompted Plato to incorporate an inundation in the Atlantis story!*

A similar Mycenaean city with a sunken harbour, tentatively named Korphos-Kalamianos on the Saronic Gulf, 60 miles south-west of Athens, has recently been excavated.

In 2014, work began on the exploration of another sunken Bronze Age coastal village at Kilada Bay, also in the Argolic Gulf. The team of Swiss and Greek archaeologists returned to the site in 2015, revealing their discoveries in August of that year(a).

Acording to Apollodorus and John Lemprière, Atalanta was the name of the only female Argonaut!(b)

> (a) Bronze Age Greek city found underwater (archive.org)<

(b) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argonauts#The_crew_of_the_Argo