Ernst Ludwig Krause

Vinci, Felice

Felice Vinci (1946- ) is an Italian nuclear engineer with a background in Latin and Greek studies  and is a member of MENSA, Italy. He believes that Greek mythology had its origins in Northern Europe.

and is a member of MENSA, Italy. He believes that Greek mythology had its origins in Northern Europe.

His first book on the subject in 1993, Homericus Nuncius[1358], was subsequently expanded into Omero nel Baltico[0018] and published in 1995. It has now been translated into most of the languages of the Baltic as well as an English version with the title of The Baltic Origins of Homer’s Epic Tales[0019]. The foreword was written by Joscelyn Godwin.

Vinci explained that “I have been interested in the Greek poet Homer and Greek mythology since I was seven years old. My elementary school teacher gave me a book about the Trojan War, so the leading characters of Homer’s poem, ‘Iliad,’ were as important for me as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck.

“In 1992, I found the Greek historian Plutarch‘s key-indication which positioned the island Ogygie in the North Atlantic ocean. I decided to dedicate myself to this research. The ancient Greek that I had studied in secondary school helped me very much. Subsequently, I was helped and encouraged by Professor Rosa Calzecchi Onesti, a famous scholar who has translated both of Homer’s poems, ‘Iliad’ and ‘Odyssey,’ into Italian. Her translations are considered a point of reference for scholars in Italy.”(s)

Readers might find two short reviews of Vinci’s book on an Icelandic website (in English) of interest(t)(u).

However, the idea of a northern source for Homeric material is not new. In the seventeenth century, Olof Rudbeck insisted that the Hyperboreans were early Swedes and by extension, were also Atlanteans. In 1918, an English translation of a paper by Carus Sterne (Dr Ernst Ludwig Krause)(1839-1903) was published with the title of The Northern Origin of the Story of Troy(m).

Vinci offers a compelling argument for re-reading Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey with the geography of the Baltic rather than the Mediterranean as a guide. A synopsis of his research is available on the Internet(a).

His book has had positive reviews from a variety of commentators(j). Understandably, Vinci’s theory is not without its critics whose views can also be found on the internet(d)(b)and in particular I wish to draw attention to one extensive review by Andreas Pääbo which is quite critical(k).>His objections are based on a firm contention that the Odyssey and the Iliad came from two different authors(v).<

Stuart L. Harris has written a variety of articles for the Migration and Diffusion website(c) including a number specifying a Finnish location for Troy following a meeting with Vinci in Rome. M.A. Joramo was also influenced by Vinci’s work and has placed the backdrop to Homer’s epic works in northern European regions, specifically identifying the island of Trenyken, in Norway’s Outer Lofoten Islands, with Homer’s legendary Thrinacia. An Italian article also links the Lofotens with some of Homer’s geographical references(r).

Jürgen Spanuth based his Atlantis theory[015] on an unambiguous identification of the Atlanteans with the Hyperboreans of the Baltic region. More specifically, he was convinced [p88] that the Cimbrian peninsula or Jutland, comprised today of continental Denmark and part of northern Germany had been the land of the Hyperboreans.

As a corollary to his theory, Vinci feels that the Atlantis story should also be reconsidered with a northern European origin at its core. He suggests that an island existed in the North Sea between Britain and Denmark during the megalithic period that may have been Plato’s island. He also makes an interesting observation regarding the size of Atlantis when he points out that ‘for ancient seafaring peoples, the ‘size’ of an island was the length of its coastal perimeter, which is roughly assessable by circumnavigating it’. Consequently, Vinci contends that when Plato wrote of Atlantis being ‘greater’ than Libya and Asia together he was comparing the perimeter of Atlantis with the ‘coastal length’ of Libya and Asia.

Malena Lagerhorn, a Swedish novelist, has written two books, in English, entitled Ilion [1546] and Heracles [1547], which incorporate much of Vinci’s theories into her plots(l). She has also written a blog about the mystery of Achilles’ blond hair(n).

Alberto Majrani is another Italian author, who, influenced by Vinci, is happy to relocate the origins of many Greek myths to the Nordic regions [1875]. Although his focus is on the Homeric epics, he has also touched on Plato’s Atlantis story, proposing, for example, that the Pillars of Heracles were a reference to the thousands of basaltic columns, known as the ‘Giant’s Causeway’ to be found on the north coast of Ireland with a counterpart across the sea in Scotland’s Isle of Staffa.(o)

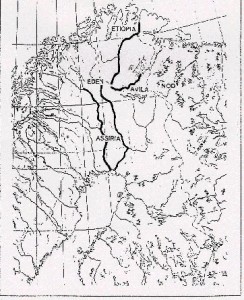

Not content with moving the geography of Homer and Plato to the Baltic, Vinci has gone further and transferred[1178] the biblical Garden of Eden to the same region(e). Then in a more recent blog(q) he repeats his views on the location of Eden in Lapland and reiterates his core thesis that “the real scenario of the events of the Iliad and the Odyssey was the Baltic-Scandinavian world, the primitive seat of the blond Achean navigators: they subsequently descended into the Mediterranean, where, around the beginning of the sixteenth century BC., they founded the Mycenaean civilization.”

A 116 bullet-pointed support for Vinci from a 2007 seminar, “Toija and the roots of European civilization” has been published online(h). In 2012 John Esse Larsen published a book[1048] expressing similar views.

An extensive 2014 audio recording of an interview with Vinci on Red Ice Radio is available online(f). It is important to note that Vinci is not the first to situate Homer’s epics in the Atlantic, northern Europe and even further afield. Henriette Mertz has Odysseus wandering across the Atlantic, while Iman Wilkens also gives Odysseus a trans-Atlantic voyage and just as controversially locates Homer’s Troy in England[610]. Edo Nyland has linked the story of Odysseus with Bronze Age Scotland[394].

An extensive 2014 audio recording of an interview with Vinci on Red Ice Radio is available online(f). It is important to note that Vinci is not the first to situate Homer’s epics in the Atlantic, northern Europe and even further afield. Henriette Mertz has Odysseus wandering across the Atlantic, while Iman Wilkens also gives Odysseus a trans-Atlantic voyage and just as controversially locates Homer’s Troy in England[610]. Edo Nyland has linked the story of Odysseus with Bronze Age Scotland[394].

Christine Pellech has daringly proposed in a 2011 book[0640], that the core narrative in Homer’s Odyssey is a description of the circumnavigation of the globe in a westerly direction(i). These are just a few of the theories promoting a non-Mediterranean backdrop to the Illiad and Odyssey. They cannot all be correct and probably all are wrong. Many have been seduced by their novelty rather than their provability. For my part I will, for now, stick with the more mundane and majority view that Homer wrote of events that took place mainly in the central and eastern Mediterranean. Armin Wolf offers a valuable overview of this notion(g).

It is worth noting that Bernard Jones has recently moved [1638] Troy to Britain, probably in the vicinity of Cambridge! Like many others, he argues that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey were not set in the Mediterranean as so many of the details that he provides are incompatible with the characteristics of that sea. However, Jones has gone further and claimed that there are details in Virgil’s Aeneid, which are equally inconsistent with the Mediterranean[p.6-10], requiring a new location!

Felice Vinci is also a co-author (with Syusy Blady, and Karl Kello) of Il meteorite iperboreo [1906] in which the Kaali meteor is discussed along with its possible association with the ancient Greek story of Phaeton.

More recently, Vinci wrote a lengthy Preface(p) to Marco Goti‘s book, Atlantide: mistero svelato[1430], which places Atlantis in Greenland!

(a) The Location of Troy | Felice Vinci (archive.org)

(b) https://mythopedia.info/Vinci-review.pdf

(c) http://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?authorid=113

(d) https://homergeography.blogspot.ie/

(e) http://www.cartesio-episteme.net/episteme/epi6/ep6-vinci2.htm

(f) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6QPtcZWBPs

(g) Wayback Machine (archive.org) See: Note 5

(h) https://www.slideshare.net/akela64/1-aa-toija-2007-English

(i) https://www.migration-diffusion.info/books.php

(j) https://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?id=44

(k) https://www.paabo.ca/reviews/BalticHomericVinci.html

(m) The Open Court magazine. Vol.XXXII (No.8) August 1918. No. 747

(n) https://ilionboken.wordpress.com/insight-articles/the-mystery-of-achilless-blond-hair/

(o) https://ilionboken.wordpress.com/insight-articles/guest-article-where-were-the-pillars-of-hercules/

(p) Atlantis: Mystery Unveiled – The Tapestry of Time (larazzodeltempo.it)

(s) https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/educational-magazines/vinci-felice-1946

(v) (26) The Odyssey’s Northern Origins and a Different Author Than Homer | Andres Pääbo – Academia.edu *

Troy *

Troy is believed to have been founded by Ilus, son of Troas, giving it the names of both Troy and Ilios (Ilium) with some minor variants.

“According to new evidence obtained from excavations, archaeologists say that the ancient city of Troy in northwestern Turkey may have been more than six centuries older than previously thought. Rüstem Aslan, who is from the Archaeology Department of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (ÇOMU), said that because of fires, earthquakes, and wars, the ancient city of Troy had been destroyed and re-established numerous times throughout the years.” This report pushes the origins of this famous city back to around 3500 BC(s).

Dating Homer’s Troy has produced many problems. Immanuel Velikovsky has drawn attention to some of these difficulties(aa). Ralph S. Pacini endorsed Velikovsky’s conclusion that the matter could only be resolved through a revised chronology. Pacini noted that “the proposed correction of Egyptian chronology produces a veritable flood of synchronisms in the ancient middle east, affirming many of the statements by ancient authors which had been discarded by historians as anachronisms.”(z)

The precise date of the ending of the Trojan War continues to generate comment. A 2012 paper by Rodger C. Young and Andrew E. Steinmann has offered evidence that the conclusion of the conflict occurred in 1208 BC, which agrees with the date recorded on the Parian Marble(ah). This obviously conflicts with the date calculated by Eratosthenes of 1183 BC. A 2009 paper(ai) by Nikos Kokkinos delves into the methodology used by Eratosthenes to arrive at this date. Peter James has listed classical sources that offered competing dates ranging from 1346 BC-1127 BC, although Eratosthenes’ date had more general acceptance by later commentators [46.327] and still has support today.

New dating for the end of the Trojan War has been presented by Stavros Papamarinopoulos et al in a paper(aj) now available on the Academia.edu website. Working with astronomical data relating to eclipses in the 2nd millennium BC, they have calculated the ending of the War to have taken place in 1218 BC and Odysseus’ return in 1207 BC.

The city is generally accepted by modern scholars to have been situated at Hissarlik in what is now northwest Turkey. Confusion over identifying the site as Troy can be traced back to the 1st century AD geographer Strabo, who claimed that Ilion and Troy were two different cities!(t) In the 18th century, many scholars consider the village of Pinarbasi, 10 km south of Hissarlik, as a more likely location for Troy.

The Hisarlik “theory had first been put forward in 1821 by Charles Maclaren, a Scottish newspaper publisher and amateur geologist. Maclaren identified Hisarlik as the Homeric Troy without having visited the region. His theory was based to an extent on observations by the Cambridge professor of mineralogy Edward Daniel Clarke and his assistant John Martin Cripps. In 1801, those gentlemen were the first to have linked the archaeological site at Hisarlik with historic Troy.”(m)

The earliest excavations at Hissarlik began in 1856 by a British naval officer, John Burton. His work was continued in 1863 until 1865 by an amateur researcher, Frank Calvert. It was Calvert who directed Schliemann to Hissarlik and the rest is history(j).

However, some high-profile authorities, such as Sir Moses Finley (1912-1986), have denounced the whole idea of a Trojan War as fiction in his book, The World of Odysseus [1139]. Predating Finley, in 1909, Albert Gruhn argued against Hissarlik as Troy’s location(i).

Not only do details such as the location of Troy or the date of the Trojan War continue to be matters for debate, but surprisingly, whether the immediate cause of the Trojan War, Helen of Troy was ever in Troy or not, is another source of controversy. A paper(ab) by Guy Smoot discusses some of the difficulties. “Odysseus’, Nestor’s and Menelaos’ failures to mention that they saw or found Helen at Troy, combined with the fact that the only two witnesses of her presence are highly untrustworthy and problematic, warrant the conclusion that the Homeric Odyssey casts serious doubts on the version attested in the Homeric Iliad whereby the daughter of Zeus was detained in Troy.”

The Swedish scholar, Martin P. Nilsson (1874-1967) who argued for a Scandinavian origin for the Mycenaeans [1140], also considered the identification of Hissarlik with Homer’s Troy as unproven.

A less dramatic relocation of Troy has been proposed by John Chaple who placed it inland from Hissarlik. This “theory suggests that Hisarlik was part of the first defences of a Trojan homeland that stretched far further inland than is fully appreciated now and probably included the entire valley of the Scamander and its plains (with their distinctive ‘Celtic’ field patterns). That doesn’t mean to say that most of the battles did not take place on the Plain of Troy near Hisarlik as tradition has it but this was only the Trojans ‘front garden’ as it were, yet the main Trojan territory was behind the defensive line of hills and was vastly bigger with the modern town of Ezine its capital – the real Troy.” (af)

Troy as Atlantis is not a commonly held idea, although Strabo, suggested such a link. So it was quite understandable that when Swiss geo-archaeologist, Eberhard Zangger, expressed this view [483] it caused quite a stir. In essence, Zangger proposed(g) that Plato’s story of Atlantis  was a retelling of the Trojan War.

was a retelling of the Trojan War.

For me, the Trojan Atlantis theory makes little sense as Troy was to the northeast of Athens and Plato clearly states that the Atlantean invasion came from the west. In fact, what Plato said was that the invasion came from the ‘Atlantic Sea’ (pelagos). Although there is some disagreement about the location of this Atlantic Sea, all candidates proposed so far are west of both Athens and Egypt.(Tim.24e & Crit. 114c)

Troy would have been well known to Plato, so why did he not simply name them? Furthermore, Plato tells us that the Atlanteans had control of the Mediterranean as far as Libya and Tyrrhenia, which is not a claim that can be made for the Trojans. What about the elephants, the two crops a year or in this scenario, where were the Pillars of Heracles?

A very unusual theory explaining the fall of Troy as a consequence of a plasma discharge is offered by Peter Mungo Jupp on The Thunderbolts Project website(d) together with a video(e).

Zangger proceeded to re-interpret Plato’s text to accommodate a location in North-West Turkey. He contends that the original Atlantis story contains many words that have been critically mistranslated. The Bronze Age Atlantis of Plato matches the Bronze Age Troy. He points out that Plato’s reference to Atlantis as an island is misleading, since, at that time in Egypt where the story originated, they frequently referred to any foreign land as an island. He also compares the position of the bull in the culture of Ancient Anatolia with that of Plato’s Atlantis. He also identifies the plain mentioned in the Atlantis narrative, which is more distant from the sea now, due to silting. Zangger considers these Atlantean/Trojans to have been one of the Sea Peoples who he believes were the Greek-speaking city-states of the Aegean.

Rather strangely, Zangger admits (p.220) that “Troy does not match the description of Atlantis in terms of date, location, size and island character…..”, so the reader can be forgiven for wondering why he wrote his book in the first place. Elsewhere(f), another interesting comment from Zangger was that “One thing is clear, however: the site of Hisarlik has more similarities with Atlantis than with Troy.”

There was considerable academic opposition to Zangger’s theory(a). Arn Strohmeyer wrote a refutation of the idea of a Trojan Atlantis in a German-language book [559].

An American researcher, J. D. Brady, in a somewhat complicated theory, places Atlantis in the Bay of Troy.

In January 2022, Oliver D. Smith who is unhappy with Hisarlik as the location of Troy and dissatisfied with alternatives offered by others, proposed a Bronze Age site, Yenibademli Höyük, on the Aegean island of Imbros(v). His paper was published in the Athens Journal of History (AJH).

To confuse matters further Prof. Arysio Nunes dos Santos, a leading proponent of Atlantis in the South China Sea places Troy in that same region of Asia(b).

Furthermore, the late Philip Coppens reviewed(h) the question marks that still hang over our traditional view of Troy.

Felice Vinci has placed Troy in the Baltic and his views have been endorsed by the American researcher Stuart L. Harris in a number of articles on the excellent Migration and Diffusion website(c). Harris specifically identifies Finland as the location of Troy, which he claims fell in 1283 BC although he subsequently revised this to 1190 BC, which is more in line with conventional thinking. The dating of the Trojan War has spawned its own collection of controversies.

However, the idea of a northern source for Homeric material is not new. In 1918, an English translation of a paper by Carus Sterne (Dr Ernst Ludwig Krause)(1839-1903) was published under the title of The Northern Origin of the Story of Troy(n). Iman Wilkens is arguably the best-known proponent of a North Atlantic Troy, which he places in Britain. Another scholar, who argues strongly for Homer’s geography being identifiable in the Atlantic, is Gerard Janssen of the University of Leiden, who has published a number of papers on the subject(u). Robert John Langdon has endorsed the idea of a northern European location for Troy citing Wilkens and Felice Vinci (w). However, John Esse Larsen is convinced that Homer’s Troy had been situated where the town Bergen on the German island of Rügen(x) is today.

Most recently (May 2019) historian Bernard Jones(q) has joined the ranks of those advocating a Northern European location for Troy in his book, The Discovery of Troy and Its Lost History [1638]. He has also written an article supporting his ideas in the Ancient Origins website(o). For some balance, I suggest that you also read Jason Colavito’s comments(p).

Steven Sora in an article(k) in Atlantis Rising Magazine suggested a site near Lisbon called ‘Troia’ as just possibly the original Troy, as part of his theory that Homer’s epics were based on events that took place in the Atlantic. Two years later, in the same publication, Sora investigated the claim for an Italian Odyssey(l). In the Introduction to The Triumph of the Sea Gods [395], he offers a number of incompatibilities in Homer’s account of the Trojan War with a Mediterranean backdrop.

Roberto Salinas Price (1938-2012) was a Mexican Homeric scholar who caused quite a stir in 1985 in Yugoslavia, as it was then when he claimed that the village of Gabela 15 miles from the Adriatic’s Dalmatian coast in what is now Bosnia-Herzegovina, was the ‘real’ location of Troy in his Homeric Whispers [1544].

More recently another Adriatic location theory has come from the Croatian historian, Vedran Sinožic in his book Naša Troja (Our Troy) [1543]. “After many years of research and exhaustive work on collecting all available information and knowledge, Sinožic provides numerous arguments that prove that the legendary Homer Troy is not located in Hisarlik in Turkey, but is located in the Republic of Croatia – today’s town of Motovun in Istria.” Sinožic who has been developing his theory over the past 30 years has also identified a connection between his Troy and the Celtic world.

Similarly, Zlatko Mandzuka has placed the travels of Odysseus in the Adriatic in his 2014 book, Demystifying the Odyssey[1396].

Fernando Fernández Díaz is a Spanish writer, who has moved Troy to Iberia in his Cómo encontramos la verdadera Troya (y su Cultura material) en Iberia [1810] (How we find the real Troy (and its material Culture) in Iberia.).

Like most high-profile ancient sites, Troy has developed its own mystique, inviting the more imaginative among us to speculate on its associations, including a possible link with Atlantis. Recently, a British genealogist, Anthony Adolph, has proposed that the ancestry of the British can be traced back to Troy in his book Brutus of Troy[1505]. Petros Koutoupis has written a short review of Adolph’s book(ad).

Caleb Howells, a content writer for the Greek Reporter website, among others, has written The Trojan Kings of Britain [2076] due for release in 2024. In it he contends that the legend of Brutus is based on historical facts. However, Adolph came to the conclusion that the story of Brutus is just a myth(ae), whereas Howells supports the opposite viewpoint.

Iman Wilkens delivered a lecture(y) in 1992 titled ‘The Trojan Kings of England’.

It is thought that Schliemann has some doubts about the size of the Troy that he unearthed, as it seemed to fall short of the powerful and prestigious city described by Homer. His misgivings were justified when many decades later the German archaeologist, Manfred Korfmann (1942-2005), resumed excavations at Hissarlik and eventually exposed a Troy that was perhaps ten times greater in extent than Schliemann’s Troy(r).

An anonymous website with the title of The Real City of Troy(ag) began in 2020 and offers regular blogs on the subject of Troy, the most recent (as of Dec. 2023) was published in Nov. 2023. The author is concerned with what appear to be other cities on the Plain of Troy unusually close to Hissarlik!

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20150912081113/https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/1995/95.02.18.html

(b) http://www.atlan.org/articles/atlantis/

(c) http://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?authorid=113

(d) https://www.thunderbolts.info/wp/2013/09/16/troy-homers-plasma-holocaust/

(e) Troy – Homers Plasma holocaust – Episode 1 – the iliad (Destructions 17) (archive.org)

(f) https://www.moneymuseum.com/pdf/yesterday/03_Antiquity/Atlantis%20en.pdf

(g) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mo-lb2AAGfY

(h) https://www.philipcoppens.com/troy.html or See: Archive 2482

(i) https://www.jstor.org/stable/496830?seq=14#page_scan_tab_contents

(j) https://turkisharchaeonews.net/site/troy

(k) Atlantis Rising Magazine #64 July/Aug 2007 See: Archive 3275

(l) Atlantis Rising Magazine #74 March/April 2009 See: Archive 3276

(m) https://luwianstudies.org/the-investigation-of-troy/

(n) The Open Court magazine. Vol.XXXII (No.8) August 1918. No. 747 See: https://archive.org/stream/opencourt_aug1918caru/opencourt_aug1918caru_djvu.txt

(o) https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/location-troy-0011933

(q) https://www.trojanhistory.com/

(r) Manfred Korfmann, 63, Is Dead; Expanded Excavation at Troy – The New York Times (archive.org)

(t) https://web.archive.org/web/20121130173504/http://www.6millionandcounting.com/articles/article5.php

(u) https://leidenuniv.academia.edu/GerardJanssen

(x) http://odisse.me.uk/troy-the-town-bergen-on-the-island-rugen-2.html

(y) https://phdamste.tripod.com/trojan.html

(z) http://www.mikamar.biz/rainbow11/mikamar/articles/troy.htm (Link broken)

(aa) Troy (varchive.org)

(ab) https://chs.harvard.edu/guy-smoot-did-the-helen-of-the-homeric-odyssey-ever-go-to-troy/

(ac) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-europe/aeneas-troy-0019186

(ad) https://diggingupthepast.substack.com/p/rediscovering-brutus-of-troy-the#details

(ae) https://anthonyadolph.co.uk/brutus-of-troy/

(af) Someplace else? Alternative locations for Troy – ASLAN Hub

(aj) http://www.academia.edu/7806255/A_NEW_ASTRONOMICAL_DATING_OF_THE_TROJAN_WARS_END