Giovanni Ugas

Ugas, Giovanni *

Giovanni Ugas is an archaeologist at the University of Cagliari, Sardinia, who has written extensively about the Shardana, their name, origin and language(c). The Shardana are usually counted as one of the Sea Peoples.

Giovanni Ugas is an archaeologist at the University of Cagliari, Sardinia, who has written extensively about the Shardana, their name, origin and language(c). The Shardana are usually counted as one of the Sea Peoples.

He has also touched on the subject of Atlantis, describing it as “a fabulous story with a political message, but this does not preclude the existence of a physical and historical substratum on which the myth is built. The task of tracing the shreds of history and geography of this story is fraught with pitfalls.”

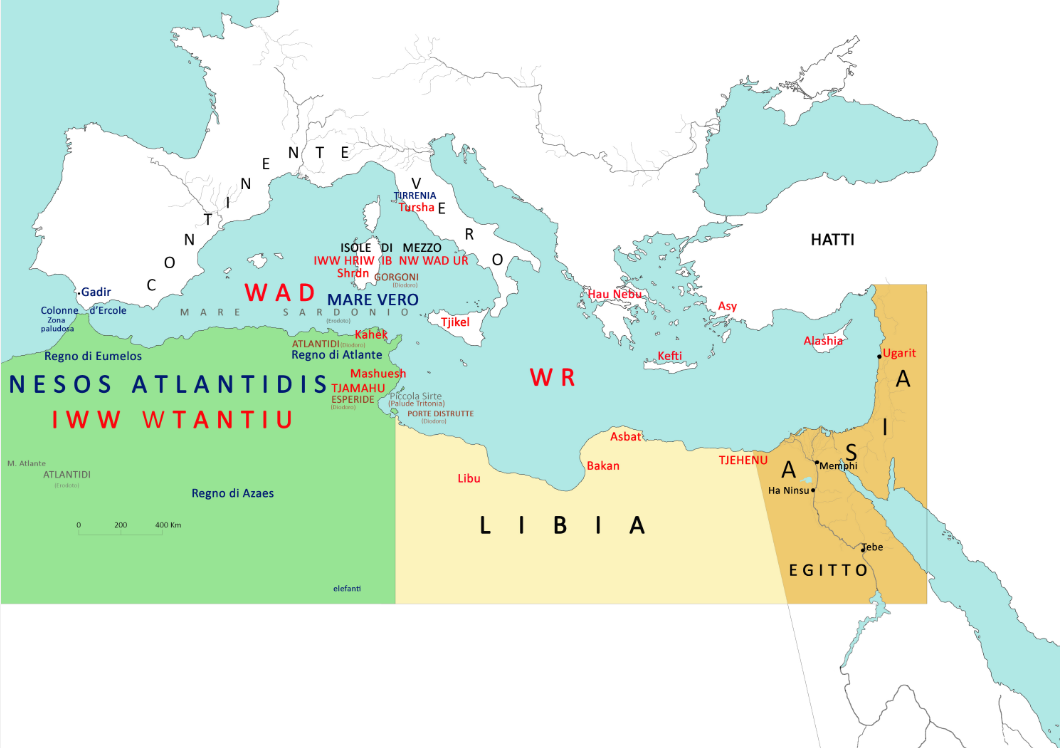

Ugas places Atlantis in northwest Africa across Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia and has concluded that in the second millennium BC, the Atlanteans joined forces with the Sea Peoples to attack Egypt.

He also claims that the Mediterranean coast of southern Spain and France, along with the Italian peninsula was the ‘true continent‘ referred to by Plato (Timaeus 25a).

(a) L’Isola del continente: L’Atlantide tra fantasia e storia (1) [di Giovanni Ugas] | Sardegna Soprattutto (archive.org) (Italian) *

(c) SP INTERVISTA>GIOVANNI UGAS: SHARDANA – Sardinia Point (archive.org)

Shardana *

The Shardana (or Sherden) is usually accepted as another name for one of the groups that comprised the maritime alliance of Sea Peoples. The earliest reference to the Shardana is in the Amarna Letters (1350 BC). However, they are also recorded as mercenaries in the Egyptian army. Since a number of writers have linked the Sea Peoples with the Atlanteans, the Shardana may be legitimately included in any comprehensive search for the truth of the Atlantis story.

The Shardana do appear to have a more complicated history than we are initially led to believe. They are first mentioned in the Amarna Letters (14th century BC.) where they are depicted as part of an Egyptian garrison, after that, some of them were part of the personal guard of Rameses II, later still they are listed as part of the Sea Peoples. A subsequent reference describes them occupying part of Phoenicia.

They are generally identified with the ancient Sardinians, who were the builders of the Nuraghi. Leonardo Melis, a Sardinian, has written extensively[478] on the subject. Links have also been proposed between the Shardana and the lost tribe of Dan and even the Tuatha De Danaan who invaded Ireland.

Trude & Moshe Dothan in their People of the Sea[1524] identify the Shardana as part of the ‘Aegean Sea Peoples’, who settled on the coast of Caanan[p.214]. They also note that “There was as well linguistic and archaeological evidence connecting them with the island of Sardinia, where Mycenaean IIIC:1b pottery was found. Sardinia may have been either their original homeland or, more probably, one of their final points of settlement.”

D’Amato & Salimbeti concluded that ” on the basis of the combined evidence from Corsica and Sardinia, it is difficult to conclude with any confidence if the Sherden originated from or later moved to this part of the Mediterranean.” They find the second theory “more reasonable.”[1152.17]

David Rohl has suggested that the Shardana had originated in Sardis in Anatolia, but “ended up settling in the western Mediterranean, first on the Italian coastal plain west of the Apennines and then in Sardinia – which is, of course, named after them – and Corsica. Their name was clearly pronounced ‘Shardana.'” [229.410]

DNA testing has shown links between Sardinia and Anatolia in Turkey. The late Philip Coppens also noted that the Sardinians are genetically different to their neighbours on Corsica and the mainland of Europe and suggested an Eastern Mediterranean origin for them.(a)

Giovanni Ugas an archaeologist at the University of Cagliari has written extensively on the subject of the Shardana, who he claims were the builders of the nuraghi. Ugas has also touched on the subject of Atlantis, which he locates in northwest Africa(b), across Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.

The Cogniarchae website(d) has proposed a number of possible locations as the original homeland of the Shardana, finishing with a look at Sarmatia (now Central Ukraine) – “Moreover, the term Shardan has clearly more roots in this part of the world than anywhere else. Namely, Sardanapalus was the name of the last Assyrian king, and many names are containing Shar and Shardan in ancient Persia and Assyria. In fact, the word “Shar” is closely related to the words “Shah” and “tzar” – all meaning “king, emperor”. Shar Kalli Shari was an Akkadian king from the 3rd millennium BC.”

Obviously further research is required to try to establish with greater certainty the exact origins of the Shardana and their links, if any, with Sardinia and/or Atlantis.

(a) (See: Archive 2131)

(b) L’Isola del continente: L’Atlantide tra fantasia e storia (1) [di Giovanni Ugas] | Sardegna Soprattutto (archive.org) (Italian) *

(c) SP INTERVISTA>GIOVANNI UGAS: SHARDANA – Sardinia Point (archive.org)

(d) Origins of the “sea peoples” – The Sherden, the Shekelesh, the Peleset – COGNIARCHAE *

Continent *

The term ‘Continent’, is derived from the Latin terra continens, meaning ‘continuous land’ and in English is relatively new, not coming into use until the Middle English period (11th-16th centuries). Apart from that, it is sometimes used to imply the mainland. The Scottish island of Shetland is known by the smaller islands in the archipelago as Mainland, its old Norse name was Megenland, which means mainland. In turn, the people of Mainland, Shetland, will apply the same title to Britain, who in turn apply the term ‘continuous land’ or continent to mainland Europe. It seems that the term is relative.

The term has been applied arbitrarily by some commentators to Plato’s Atlantis, usually by those locating it in the Atlantic. Plato never called Atlantis a continent, but instead, as the sixteen instances below prove, he consistently referred to it as an island, probably the one containing the capital city of the confederation or alliance!

[Timaeus 24e, 25a, 25d Critias 108e, 113c, 113d, 113e, 114a, 114b, 114e, 115b, 115e, 116a, 117c, 118b, 119c]

Several commentators have assumed that when Plato referred to an ‘opposite continent’ he was referring to the Americas, however, Herodotus, who flourished after Solon and before Plato, was quite clear that there were only three continents known to the Greeks, Europe, Asia and Libya (4.42). In fact, before Herodotus, only two landmasses were considered continents, Europe and Asia, with Libya sometimes considered part of Asia. Furthermore, Anaximander drew a ‘map’ of the known world (left), a century after Herodotus, showing only the three continents, without any hint of territory beyond them.

Nevertheless, there has always been a school of thought that supported the idea of the ancient Greeks having knowledge of the Americas. In 1900, Peter de Roo in History of America before Columbus [890] not only supported this contention but suggested further that ancient travellers from America had travelled to Europe [Vol.1.Chap 5].

Daniela Dueck in her Geography in Classical Antiquity [1749] noted that “Hecataeus of Miletus divided his periodos gês into two books,each devoted to one continent, Europe and Asia, and appended his description of Egypt to the book on Asia. In his time (late sixth century bce), there was accordingly still no defined identity for the third continent. But in the fifth century the three continents were generally recognized, and it became common for geographical compositions in both prose and poetry to devote separate literary units to each continent.”

So when Plato does use the word ‘continent’ [Tim. 24e, 25a, Crit. 111a] we can reasonably conclude that he was referring to one of these landmasses, and more than likely to either Europe or Libya (North Africa) as Atlantis was in the west, ruling out Asia.

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(b) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). It would seem that in this particular circumstance the term ‘Sicilian Strait’ refers to the Strait of Messina, which is another example of how ancient geographical terms often changed their meaning over time (see Atlantic & Pillars of Herakles).

The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(d). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. This would push the custom of referring to Italy as a ‘continent’ back to the time of Plato, who clearly states (Tim. 25a) that the Atlantean alliance “ruled over all the island, over many other islands as well. and over sections of the continent.” (Wells). The next passage recounts their control of territory in Europe and North Africa, so it naturally begs the question as to what was ‘the continent’ referred to previously? I suggest that the context had a specific meaning, which, in the absence of any other candidate and the persistent usage over the following two millennia can be reasonably assumed to have been southern Italy.

Centuries later, the historian, Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) refers at least twice[1523.6.209/10] to the ‘continent of Italy’. More recently, Armin Wolf (1935- ), the German historian, when writing about Scheria relates(a) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” This continuing usage of the term is confirmed by a current travel site(c) and by author, Robert Fox in The Inner Sea [1168.141].

I suggest that Plato similarly used the term and can be seen as offering a more rational explanation for the use of the word ‘continent’ in Timaeus 25a, adding to the idea of Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean.

Giovanni Ugas claims that the Mediterranean coast of southern Spain and France, along with the Italian peninsula constituted the ‘true continent’ (continente vero) referred to by Plato. (see below)

Furthermore, the text informs us that this opposite continent surrounds or encompasses the true ocean, a description that could not be applied to either of the Americas as neither encompasses the Atlantic, which makes any theory of an American Atlantis more than questionable.

Modern geology has definitively demonstrated that no continental mass lies in the Atlantic and quite clearly the Mediterranean does not have room for a sunken continent.

(a) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(b) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(c) Four Ways to Do Sicily – Articles – Departures (archive.org)

(e) The Elusive Location of Atlantis Part 1 – Luciana Cavallaro (archive.org) *

Algeria *

Algeria is the largest nation by area in Africa and the tenth largest in the world. Most of the population lives in the fertile north, while most of the country is rather arid, including part of the Sahara. Over two thousand years ago, when the climate was more benign, Algeria along with its neighbour, Tunisia, as well as Egypt, were the ‘breadbaskets’ of Rome.

Since the early 18th century Atlantis has been associated by a number of researchers with Algeria, often linked with Tunisia and/or Morocco. These included Ali Bey El Abbassi, Robert Schmalz, Giovanni Ugas and the American researcher Gerald Wells(a) who specified the western Algerian province of El Bayadh as the location of Atlantis. He offered its exact coordinates as 31.84°N Latitude and 103.03°E Longitude and added that the Garden of Eden had existed in the same region!

A more frequent suggestion is that the chotts of Algeria and Tunisia had been the location of the legendary Lake Tritonis when the Sahara was a more fertile place with a wetter climate. Ulrich Hofmann supports this view while Alberto Arecchi contends that Lake Tritonis was the ‘Atlantic Sea’ referred to by Plato, with the Pillars of Heracles situated at the Gulf of Gabes. A related claim has been made recently by Hong-Quen Zhang(b).

A more frequent suggestion is that the chotts of Algeria and Tunisia had been the location of the legendary Lake Tritonis when the Sahara was a more fertile place with a wetter climate. Ulrich Hofmann supports this view while Alberto Arecchi contends that Lake Tritonis was the ‘Atlantic Sea’ referred to by Plato, with the Pillars of Heracles situated at the Gulf of Gabes. A related claim has been made recently by Hong-Quen Zhang(b).

(a) Atlantis-Bakhu | Wells Research Laboratory (archive.org) * ^6 pages

(b) https://medcraveonline.com/IJH/is-atlantis-related-to-the-green-sahara.html