Melqart

Poseidon

Poseidon was one of the twelve Olympians of ancient Greek mythology. He was also the Greek god of the sea who was given the island of Atlantis as his realm. The Romans later knew Poseidon as Neptune. Herodotus (II.50.2) claimed that the Greek gods were imported from Egypt with a few exceptions including Poseidon. Some have suggested that the ancient Egyptian god Sobek was the equivalent of Poseidon, but the connection seems rather tenuous.

Poseidon was one of the twelve Olympians of ancient Greek mythology. He was also the Greek god of the sea who was given the island of Atlantis as his realm. The Romans later knew Poseidon as Neptune. Herodotus (II.50.2) claimed that the Greek gods were imported from Egypt with a few exceptions including Poseidon. Some have suggested that the ancient Egyptian god Sobek was the equivalent of Poseidon, but the connection seems rather tenuous.

>Eire Rautenberg has proposed that Poseidon was not originally a Greek god but instead came from the Libyans of North Africa(b).<

Some writers have suggested that Noah was to be equated with Poseidon. His symbol was a trident.

Poseidon is also credited with having been the first to tame horses. Others, such as Nienhuis, have equated Poseidon with Sidon referred to in Genesis 10:15.

The Phoenician sea god Melqart is frequently seen as the son of Poseidon whereas others, such as Jonas Bergman, consider them to be identical. The Nordic sea god Aegir is also seen as a mirror of Poseidon. In Portugal, Saint Bartholomew is considered a Christianised Poseidon, where statues of him are similar to those of Poseidon including a trident.

The Celtic god of the sea was known as Manannán Mac Lir who is frequently associated with the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea.

When the Greek gods divided the world among themselves, Poseidon received Atlantis as his share. He fell in love with a mortal, Clieto, who bore him five sets of twin boys, of whom Atlas was the firstborn and primus inter pares. Atlantis was then shared between them.

In December 2017, Anton Mifsud, Malta’s leading Atlantologist, published an intriguing suggestion(a) , when he pointed out that on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, painted by Neo-Platonist Michelangelo, something odd can be perceived in the central panel, known as The Creation of Adam. There, we find ‘god’ surrounded by five pairs of flightless ‘cherubs’. This is reminiscent of Poseidon’s five pairs of twin sons. Atlantis. However, Christian iconography invariably shows cherubs with wings, so it begs the question; why this departure from the norm? Mifsud contends that together with other aspects of the fresco, this depiction is closer to Plato’s ‘god’, Poseidon, than that of the Mosaic creator in Genesis!

(a) https://www.academia.edu/35425812/THE_CREATION_OF_ADAM_-_Genesis_or_Plato?auto=download

(b) Poseidon is not a Greek god! – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog) *

Melqart

Melqart was the son of El the supreme deity of the Phoenicians. He was the  principal god of the city of Tyre and was sometimes known as Baal. As Tyre gained supremacy throughout the Phoenician world, Melqart also gained prominence. Melqart is the only Phoenician god mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. The Temple of Melqart in Tyre was similar to that built for Solomon in Jerusalem. This is understandable as craftsmen from Tyre built the temple in Jerusalem and there would have had a natural exchange of religious ideas, as they were neighbours. Herodotus describes the main entrance to the sanctuary as being flanked by two columns or pillars known as ‘betyls’, one made of gold and the other of ‘smaragdus’— often translated as ‘emerald.’

principal god of the city of Tyre and was sometimes known as Baal. As Tyre gained supremacy throughout the Phoenician world, Melqart also gained prominence. Melqart is the only Phoenician god mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. The Temple of Melqart in Tyre was similar to that built for Solomon in Jerusalem. This is understandable as craftsmen from Tyre built the temple in Jerusalem and there would have had a natural exchange of religious ideas, as they were neighbours. Herodotus describes the main entrance to the sanctuary as being flanked by two columns or pillars known as ‘betyls’, one made of gold and the other of ‘smaragdus’— often translated as ‘emerald.’

The cult of Melqart was brought to Carthage, the most successful Tyrian colony, and temples dedicated to Melqart are found in at least three sites in Spain; Gades (modern Cadiz), Ebusus, and Carthago Nova. Near to Gades, at the Strait of Gibraltar, the mountains on either side were first known as the Pillars of Melqart, and then later changed to the Pillars of Heracles. Across the Strait of Gibraltar, at the Atlantic coast of Morocco was the Phoenician colony of Lixus, where there was another temple of Melqart.

In classical literature, Melqart and Heracles have been referred to interchangeably, by many historians such as Josephus Flavius.

It is thought that the city of Cadiz was originally founded as Gadir (walled city) by the Phoenicians around 1100 BC, although hard evidence does not prove a date earlier than the 9th century BC. In his 2011 book, Ancient Phoenicia, Mark Woolmer has claimed [1053.46] that the archaeological evidence indicates a date around the middle of the 8th century BC.

It is regarded as the most ancient functioning city in Western Europe. Gadir had a temple that was dedicated to the Phoenician god Melqart. Some consider that the columns of this temple were the origin of the reference of the Columns of Heracles. Commentators on Plato’s Atlantis story have linked Cadiz (formerly Gades) with the second son of Poseidon, Gadirus.

Heracles

Heracles (Herakles) was a Greek mythical hero(c), later known to the Romans as Hercules. He is one of several mythical heroes who were reportedly abandoned as babies(f).

There is also a claim that the Greek Herakles had a much earlier namesake the patron of Tyre and known as Melqart, which translates as ‘king of the city’. “Melqart was considered by the Phoenicians to represent the monarchy, perhaps the king even represented the god, or vice-versa, so that the two became one and the same. The ruler was known by the similar term mlk-qrt, and the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel criticises the kings of Tyre for considering themselves god on earth”(i).

He has also been identified with the biblical Samson(a) and the Mesopotamian Gilgamesh(b). Dhani Irwanto who claims that Atlantis was situated in Indonesia has tried to link Herakles with the Javanese mythical figure of Kala [1093.118]. However, Dos Santos who also advocated an Atlantis location in the same region decided that Hercules was originally the Hindu hero Vishnu [320.129], quoting Megasthenes (350-290 BC), the Greek geographer, in support of his contention. Others have referred to Megasthenes as identifying Hercules with Krishna(e)(g). The list of associations seems to go on and on, including the Scandanavian Hoder, Akkadian Nergal, Roman Mars and Ireland’s Cú Chulainn(h).

The penitential twelve labours of Hercules have long been associated with the zodiac(j), which is reminiscent of the warriors in the Iliad who have also been associated with the zodiac!(k) Alice A. Bailey was probably the best-known exponent of this back in the 1980s, in The Labours of Hercules [1163].

He is usually portrayed as brandishing a club and wearing a lion’s head as a helmet, probably because he, like Samson, reputedly unarmed, overcame lions, but the similarities don’t end there(a).

Euhemerists have suggested that he was a real historical figure, possibly a former king of Argos.

James Bailey noted [149.322] that Diodorus Siculus wrote in different books of his Histories that Heracles was born in India and Egypt!

A more controversial suggestion has been made by Emmet J. Sweeney, in his 2001 book, Arthur and Stonehenge[0918], in which the blurb for the book claims that “Arthur himself, he was the primitive bear-god “Artos”, the Celtic version of Hercules. Originally portrayed with a bear-skin over his head and shoulders and carrying a great oaken club, he became the prototype of the Greek Hercules when Hellenic traders, braving the wild waters of the Atlantic in search of tin, heard his story from the Britons.” However, Sweeney also identifies Moses “as an alter ego of Hercules.” in his Atlantis: The Evidence of Science[700.198].

There appears to have been a cult of Heracles that may have extended as far as Britain, where the Cerne Abbas chalk figure is sometimes claimed to represent him(d).

The term ‘Pillars of Heracles’ was used by the ancient Greeks to define the outer reaches of their limited seagoing range. This changed over time as their nautical capabilities improved. Some of the earlier ‘Pillars’ were located at the entrance to the Black Sea and the Strait of Sicily and the Strait of Messina. Later the term was applied exclusively to the Strait of Gibraltar.

(a) Archive 3444

(b) https://phoenicia.org/greek.html

(c) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heracles

(d) https://www.britainexpress.com/counties/dorset/ancient/cerne-abbas.htm

(e) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megasthenes’_Herakles

(f) https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/moses-as-abandoned-hero/

(g) Shri Krishna and Hercules – indian and greek mythology – Indian mythology (archive.org)

(h) https://www.aeonjournal.com/articles/samson/samson.html

(i) https://edukalife.blogspot.com/2015/01/congregation-bible-study-week-starting.html

(j) The Twelve Labours of Hercules (Herakles) (archive.org) *

Carteia

Carteia was a Phoenician port situated in South-West Spain just west of the Rock of Gibraltar (36.2N, 5.4W). Today there is little to be seen as the harbour silted up and was abandoned. It has been suggested that it may have derived its name from the Phoenician god Melqart. Some researchers such as Karl Jürgen Hepke have linked it with Tartessos/Atlantis, following the same incorrect identification made by Pliny (Natural History 3.7) in the 1st century AD.

Pharos

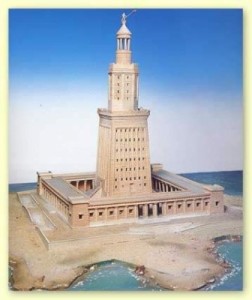

Pharos in the Nile Delta has been suggested by R. McQuillen as the location of Atlantis. It should be noted that the cities of Canopus and Herakleion in the same area were submerged, apparently due to liquefaction(h), following an earthquake between 731 and 743 BC. If something similar occurred to Atlantis situated at Pharos it might explain the shoals of mud reported by Plato and may even have been the reason for the erection of the famous lighthouse there, completed around 280 BC.

Pharos in the Nile Delta has been suggested by R. McQuillen as the location of Atlantis. It should be noted that the cities of Canopus and Herakleion in the same area were submerged, apparently due to liquefaction(h), following an earthquake between 731 and 743 BC. If something similar occurred to Atlantis situated at Pharos it might explain the shoals of mud reported by Plato and may even have been the reason for the erection of the famous lighthouse there, completed around 280 BC.

This lighthouse at Pharos took 20 years to build and is reported to have been as much as 450 feet in height, topped with a statue of Poseidon (or Zeus). It is claimed that there was also a furnace on top which, according to Robert Temple [928], suggested that some form of mirror reflected light out to sea. There is evidence from writers as early as Homer that nocturnal sea travel was commonplace in ancient times(d), so some system of beacons to assist this, would have been a natural development.

Themistocles (524-459 BC) is traditionally credited with having established the first Greek lighthouse at Athens’ port, Piraeus, in the 5th century BC, which was a column with a beacon on top.

The coining of ‘pharology’ as a term to describe the study of lighthouses is generally credited to the British hydrographer John Purdy (1773-1843).

In a study of ancient lighthouses (pharology) by Ken Trethewey(a), now a retired marine engineer, he indicates that there were probably precursors to the Alexandrian edifice, but that there is no archaeological evidence to support this contention. Just as New York’s Empire State Building could not have been built without the preceding decades of evolution of building methods, similarly, the magnificent Pharos lighthouse must have had forerunners.

Another suggestion is that altars, temples and latterly Christian churches frequently situated at the end of promontories may have functioned initially as navigational aids, keeping in mind that early Mediterranean seafarers preferred coastal hugging to open sea travel. I would think it strange if such locations were not used for beacons.

A book review by Terrance M.P. Duggan draws attention to the use of the word ‘pharos’ as far back as Homer’s time, centuries before the Alexandrine structure was built(c). Duggan has also noted in an extensive study of ancient beacons(d) how “sailing at night was practiced in antiquity, first by the Phoenicians” and that “later, sailing at night is mentioned repeatedly by Homer in the Odyssey.” It must be obvious that such regular nocturnal travel could not have been achieved without the availability of some system of warning beacons.

Duggan also notes the use of false beacons such as in the story of “Palamedes’s father, the King of Naupilus or Euboea, then lit a series of false beacons leading to the shipwreck off Euboea of much of the Achaean fleet returning from the Trojan War, using false maritime navigational beacons to serve as a wrecker’s device, and with the use of these false navigational beacons quite clearly indicating the presence at this date of considerable numbers of genuine navigational beacons along coastlines to provide an expected navigational guide for ships sailing through the night.“

What I also found interesting was another quote by Duggan of a passage from Al-Mas’udi, circa 947 AD – “At the point where the Mediterranean Sea joins the Atlantic Ocean, there is a lighthouse of stone and copper (bronze), built by the giant Hercules (probably to be associated with the location of the Phoenician Temple of Melkart-Herakles on the North African side). It is covered with inscriptions and statues whose hand gestures proclaim to those coming from the Mediterranean who wish to enter the Atlantic Ocean, ‘There is no way beyond me’” This is a clear association of Heracles with a lighthouse and raises the question of whether this was a more widespread occurrence, which seems possible.

At the other end of the Mediterranean, the Colossus of Rhodes is also thought by some(g) to have functioned as a lighthouse, but at the very least was a daytime navigational marker, Heracles was also worshipped on the island as the founder of its first settlement.

The Tower of Hercules is an ancient Roman lighthouse on a peninsula about 2.4 km (1.5 mi) from the centre of the town of A Coruña, Galicia, in north-western Spain. There is also a claim that a Roman lighthouse existed at Akko (Acre), now in northern Israel, which is discussed elsewhere and supported by numismatic and archaeological evidence(i).

Massimo Rapisarda & Marcello Ranieri have now published a paper(f) pointing to possible land-based navigational aids, most likely, Phoenician, at the Sicilian promontory of Capo Gallo. They also refer to “the renowned Phoenician ability to navigate at night.”

Trethewey, a leading pharologist, published Ancient Lighthouses [1667] in 2018. Furthermore, he has also published a series of eight lengthy papers on pharology on the academia.edu website(e).

>The prolific Dr. Uday Dokras in his work on the lighthouse at Alexandria wrote that it “was certainly not the first such aid to ancient mariners but it was probably the first monumental one. Thasos, the north Aegean island, for example, was known to have had a tower-lighthouse in the Archaic period, and beacons and landmarks were widely used by cities to help sailors across the Mediterranean. Ancient lighthouses were built primarily as navigational aids for where a harbour was located rather than as a warning of hazardous shallows or submerged rocks, although, because of the dangerous waters of Alexandria’s harbour, the Pharos performed both functions.” (l)<

Other papers by Marco Vigano also investigate the subject of proto-lighthouses(b)(j), furthermore, a book review by Terrance M.P. Duggan, draws attention to the use of the word ‘pharos’ as far back as Homer’s time, centuries before the Alexandrine structure was built(c). Duggan has also written a paper on The Missing Navigational Markers(d).

A recent book, The Electric Mirror on the Pharos Lighthouse[948], edited by Larry Brian Radka, argues spiritedly for the use of electricity at Pharos!

Robert Graves suggested a number of locations as having Atlantean connections. Included in that list is Pharos(k).

(a) https://www.academia.edu/Documents/in/Ancient_lighthouses

(d) https://www.academia.edu/7665901/On_the_Missing_Navigational_Markers?auto=download

(e) https://www.academia.edu/Documents/in/Lighthouses

(g) https://www.athensjournals.gr/mediterranean/2019-5-1-2-Kebric.pdf

(h) Science Notes 2001: The Sunken Cities of Egypt (ucsc.edu)

(i) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236849769_The_Roman_Lighthouse_in_Akko_Israel

(j) http://www.arigenova.it/wail/Articoli/Pharology.pdf

(k) Pharos and the Atlantis legend – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(l) https://archive.org/stream/lighthouse-of-alexandria-book/Lighthouse%20of%20Alexandria-BOOK_djvu.txt *

Cádiz

Cádiz is the modern name for ancient Gades considered the original kingdom of Gadeirus the twin brother of Atlas. However, the certainty normally associated with this accepted identification is weakened by the fact that quite a number of locations with similar-sounding names are to be found in the Central and Western Mediterranean regions.

A Map of Cadiz circa 1813 is shown on the right.

It has also been suggested that the name Cadiz came from Gadir, which in turn was derived from Kadesh!

The Spanish historian, Adolfo Valencia wrote a history of Cádiz[0208], in which he suggested that Atlantis might have extended from Cádiz to Malta.

The Spanish historian, Adolfo Valencia wrote a history of Cádiz[0208], in which he suggested that Atlantis might have extended from Cádiz to Malta.

In 1973, Maxine Asher led an expedition to search for Atlantis off the coast of Cadiz, which despite claims of having discovered Plato’s Island, nothing verifiable was found(a). These claims received global press attention, enabling Asher to dine out on it for the rest of her fraudulent life.

It is generally accepted that the Phoenicians from Tyre founded Gadir, later to be known as Gades to the Romans. The Roman historian, Velleius Paterculus (c.19 BC – c.31 AD) wrote that Cadiz was founded 80 years after the Trojan War, circa 1100 BC. In the 9th century BC, the Phoenicians, under Princess Dido, founded a new capital at Carthage in North Africa. At Gades, the Phoenicians/Carthaginians built a temple to Melqart that had two columns that many consider to be the original Pillars of Hercules. In 2007, it was announced that excavations in the old town centre produced shards of Phoenician pottery and walls dated to the 8th century BC, probably making it the oldest inhabited city in Europe.

In early January 2022, “Archaeologists from the University of Seville and the Andalusian Institute of Historical Heritage claim to have discovered the lost Temple of Hercules Gaditanus. Using information they obtained from documentaries and aerial photographs, the researchers found a large rectangular structure submerged in the Bay of Cadiz. (b)

The structure, nearly 1,000 feet long, 500 feet wide, and matches the ancient descriptions of the temple, is only visible in low tide.”

In September 2023, the latest attempt to revive interest in a Spanish Atlantis was unveiled at a press conference in Chipiona, near Cádiz. The theme of the conference was the discovery of long underwater curved walls that some have claimed to match exactly Plato’s description of Atlantis.

Thorwald C. Franke(c) has more on the background to this effort to put the spotlight on the possibility of Atlantis being situated in this region of Spain which lies at the southern end of the Doñana Marshes that had received extensive investigation over the past couple of decades. The press conference was also used to announce the showing of a new documentary series by Michael Donnellan on October 8th in Cádiz.

Also See: Egadi Islands

(a) 1973 Atlantis Expedition (fourth-millennium.net)

(b) Spanish Archaeologists Claim to Have Discovered The Temple of Hercules (sputniknews.com)