Ferdinand Butavand

Kerkenna

Kerkennah is the name of a group of Tunisian islands situated off its east coast.*The archipelago is one of the locations claimed to include Homer’s ‘Island of Goats’ and the home of the Cyclops in the Odyssey.*

Kerkennah is the name of a group of Tunisian islands situated off its east coast.*The archipelago is one of the locations claimed to include Homer’s ‘Island of Goats’ and the home of the Cyclops in the Odyssey.*

In a recent book[980] by Antonio Usai he claims that the original Pillars of Hercules were situated between the islands and the mainland. In support of his contention he quotes fron The Voyageof Hanno and other classical writers.

Férréol Butavand thought that Atlantis had existed in the Central Mediterranean and had included the Kerkennah Islands. Alberto Arecchi has expressed similar views.

North Africa

North Africa has received considerable attention as a possible location for Atlantis since the beginning of the 19th century. Gattefosse and Butavand are names associated with early 20th-century North African theorists. They, along with Borchardt, Herrmann and others have proposed locations as far west as Lixus on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, on through Tunisia and Libya and even as far east as the Nile delta.

One of the earliest writers was Ali Bey El Abbassi who discussed Atlantis and an ancient inland sea in the Sahara. The concept of such an inland sea, usually linked with Lake Tritonis, has persisted with the Chotts of Tunisia and Algeria as prime suspects.

>There is some acceptance that a seismic or tectonic upward thrust in the vicinity of the Gulf of Gabés created a barrier that cut off this inland sea from the Mediterranean, leaving the trapped water to gradually evaporate. However, the chotts still receive some runoff from the Atlas mountains in winter, which liquefies the salty crust. Diodorus Siculus records this event (Bk.3.55) “The story is also told that the marsh Tritonis disappeared from sight in the course of an earthquake, when those parts of it which lay towards the ocean were torn asunder.” [1731a.179] However, this is more a description of the removal of a barrier, rather than the creation of one! Ludwig Borchardt suggested that this event took place around 1250 BC(c).<

If such an event did not occur, how do we explain the salt-laden chotts? However, proving a connection with Atlantis is another matter.

Whether this particular geological upheaval was related to the episode that destroyed parts of ancient Malta is questionable as the Maltese event was one of more massive subsidence.

It should be kept in mind that Plato described the southern part of the Atlantean confederation as occupying North Africa as far eastward as Egypt (Tim.25b & Crit.114c).

The exact extent of Egyptian-controlled territory in Libya at the time of Atlantis is unclear. We do know that “In the mid-13th century, Marmarica was dominated by an Egyptian fortress chain stretching along the coast as far west as the area around Marsa Matruh; by the early 12th century, Egypt claimed overlordship of Cyrenaican tribes as well. At one point a ruler chosen by Egypt was set up (briefly!) over the combined tribes of Meshwesh, Libu, and Soped.”(b) Another site(a) suggests that Egyptian control stretched nearly as far as Syrtis Major, which itself has been proposed by some as the location of Atlantis.

All this, of course, conflicts with the idea of the Atlanteans invading from beyond ‘Pillars of Heracles’ situated at Gibraltar since they apparently already controlled at least part of the Western Mediterranean as far as Italy and Egypt.

One of the principal arguments against Atlantis being located in North Africa is that Plato clearly referred to Atlantis as an island. However, as Papamarinopoulos has pointed out that regarding the Greek word for island, ‘nesos’ “a literary differentiation between ‘island’ and ‘peninsula’ did not exist in alphabetic Greek before Herodotus’ in the 5th century BC. Similarly, there was not any distinction between the coast and an island in Egyptian writing systems, up to the 5th century BC.” In conversation with Mark Adams[1070.198], Papamarinopoulos explains that in the sixth century BC, when Solon lived, ‘nesos’ had five geographic meanings. “One, an island as we know it. Two, a promontory. Three, a peninsula. Four, a coast. Five, land within a continent, surrounded by lakes, rivers or springs.”

Personally, from the context, I am quite happy to accept that the principal city of the Atlantean alliance existed on an island as we understand the word. This was probably north of Tunisia, where a number of possible candidates exist. However, it may be unwise to rule out a North African city just yet!

Another argument put forward that appears to exclude at least part of North Africa is that Plato, according to many translations, he refers to Atlantis as ‘greater’ than ‘Libya’ and ‘Asia‘ combined, using the Greek word, ‘meizon‘, which had a primary meaning of ‘more powerful’ not greater in size. Atlantis could not have been situated in either Libya or Asia because ‘a part cannot be greater than the whole’. However, if Plato was referring to military might rather than geographical extent, as seems quite likely, North Africa may indeed have been part of the Atlantean alliance, particularly as Plato describes the control of Atlantis in the Mediterranean as far as Tyrrhenia and Egypt.

(a) https://starshinetours.com/first-signs-of-weakening/ (Link broken)

(b) https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/egyptians-and-libyans-in-the-new-kingdom/

(c) Ludwig Borchardt – Dictionary of Art Historians (archive.org) *

Shoals of Mud

A Shoal of mud is stated by Plato (Tim.25d) to mark the location of where Atlantis ‘settled’. He described these shallows in the present tense, clearly implying that they were still a maritime hindrance even in Plato’s day.

Three of the most popular translations clearly indicate this:

….the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.

…..the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal of mud which the island created as it settled down.”

…..the sea in that area is to this day impassible to navigation, which is hindered by mud just below the surface, the remains of the sunken island.

Wikipedia has noted(h) that “during the early first century, the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo wrote about the destruction of Atlantis in his On the Eternity of the World, xxvi. 141, in a longer passage allegedly citing Aristotle’s successor Theophrastus.

‘ And the island of Atalantes [translator’s spelling; original: “????????”] which was greater than Africa and Asia, as Plato says in the Timaeus, in one day and night was overwhelmed beneath the sea in consequence of an extraordinary earthquake and inundation and suddenly disappeared, becoming sea, not indeed navigable, but full of gulfs and eddies’.”

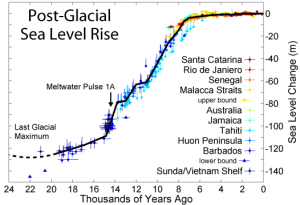

Since it is probable that Atlantis was destroyed around a thousand years or more before Solon’s Egyptian sojourn, to have continued as a hazard for such a period suggests a location that was little affected by currents or tides. The latter would seem to offer support for a Mediterranean Atlantis as that sea enjoys negligible tidal changes, as can be seen from the chart below. The darkest shade of blue indicates the areas of minimal tidal effect.

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

The reference to mud shoals resulting from an earthquake brings to mind the possibility of liquefaction. This is perhaps what happened to the two submerged ancient cities close to modern Alexandria. Their remains lie nine metres under the surface of the Mediterranean.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Some supporters of a Black Sea Atlantis have suggested the shallow Strait of Kerch between Crimea and Russia as the location of Plato’s ‘shoals’(e) .

The tidal map above offers two areas west of Athens and Egypt that do appear to be credible location regions, namely, (1) from the Balearic Islands, south to North Africa and (2), a more credible straddling the Strait of Sicily. This region offers additional features, making it much more compatible with Plato’s account.

By contrast, just over a hundred miles south of that Strait, lies the Gulf of Gabés, which boasts the greatest tidal range (max 8 ft) within the Mediterranean.

The Gulf of Gabes formerly known as Syrtis Minor and the larger Gulf of Sidra to the east, previously known as Syrtis Major, was greatly feared by ancient mariners and continue to be very dangerous today because of the shifting sandbanks created by tides in the area.

There are two principal ancient texts that possibly support the gulfs of Syrtis as the location of Plato’s ‘shoal’. The first is from Apollonius of Rhodes who was a 3rd-century BC librarian at Alexandria. In his Argonautica (Bk IV ii 1228-1250)(a) he unequivocally speaks of the dangerous shoals in the Gulf of Syrtis. The second source is the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 27 13-18) written three centuries later, which describes how St. Paul on his way to Rome was blown off course and feared that they would run aground on “Syrtis sands.” However, good fortune was with them and after fourteen days they landed on Malta. The Maltese claim regarding St. Paul is rivalled by that of the Croatian island of Mljet as well Argostoli on the Greek island of Cephalonia. Even more radical is the convincing evidence offered by Kenneth Humphreys to demonstrate that the Pauline story is an invention(b).

Both the Strait of Sicily and the Gulf of Gabes have been included in a number of Atlantis theories. The Strait and the Gulf were seen as part of a larger landmass that included Sicily according to Butavand, Arecchi and Sarantitis who named the Gulf of Gabes as the location of the Pillars of Heracles. Many commentators such as Frau, Rapisarda and Lilliu have designated the Strait of Sicily as the ‘Pillars’, while in the centre of the Strait we have Malta with its own Atlantis claims.

Zhirov[458.25] tried to explain away the ‘shoals’ as just pumice stone, frequently found in large quantities after volcanic eruptions. However, Plato records an earthquake, not an eruption and Zhirov did not explain how the pumice stone was still a hazard many hundreds of years after the event. Although pumice can float for years, it will eventually sink(c). It was reported that pumice rafts associated with the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa were found floating up to 20 years after that event. Zhirov’s theory does not hold water (no pun intended) apart from which, Atlantis was destroyed as a result of an earthquake. not a volcanic eruption and I think that the shoals described by Plato were more likely to have been created by liquefaction and could not have endured for centuries.

Nevertheless, a lengthy 2020 paper(d) by Ulrich Johann offers additional information about pumice and in a surprising conclusion proposes that it was pumice rafts that inspired Plato’s reference to shoals!

Andrew Collins in an effort to justify his Cuban location for Atlantis needed to find Plato’s ‘shoals of mud’ in the Atlantic and for me, in what seems to have been an act of desperation he decided that the Sargasso Sea fitted the bill [072.42]. Similarly, Emilio Spedicato in support of a Hispaniola Atlantis also opted for the Sargasso. However, neither Collins or Spedicato were the first to make this suggestion. Chedomille Mijatovich (1842-1932), a Serbian politician, economist and historian was one of the first in modern times to suggest that the Sargasso Sea may have been the maritime hazard described by Plato as a ‘shoal of mud’, which resulted from the submergence of Atlantis. However, neither explains how anyone can mistake seaweed for mud!

The late Andis Kaulins believed that Atlantis did exist and considered two possible regions for its location; the Minoan island of Thera or some part of the North Sea that was submerged at the end of the last Ice Age when the sea levels rose dramatically. Kaulins noted that part of the North Sea is known locally as ‘Wattenmeer’ or Sea of Mud’ reminiscent of Plato’s description of the region where Atlantis was submerged, after that event.

An even more absurd suggestion came from the American scholar William Arthur Heidel (1868-1941), who denied the reality of Atlantis and wrote a critical paper [0374] on the subject (republished July 2013(g)). He claimed that an expeditionary naval force sent by Darius in 515 BC under Scylax of Caryanda to explore the Indus River, eventually encountered waters too shallow for his ships, and that this was the inspiration behind Plato’s tale of unnavigable seas. Heidel further claimed that Plato’s battle between Atlantis and Athens is a distorted account of the war of invasion between the Persians and the peoples of the Indus Valley (Now Pakistan)!

(a) https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/argo/argo53.htm

(b) The Curious Yarn of Paul’s “Shipwreck” (archive.org) *

(c) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170523144110.htm

(e) Index (atlantis-today.com)

(f) https://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread61382/pg1

(g) A Suggestion concerning Plato’s Atlantis on JSTOR (archive.org)

(h) Atlantis – Wikipedia_?s=books&ie=UTF&qid=1376067567&sr=-