Madeira

d’Ascanio, Alfonso

Alfonso d’Ascanio is a Spanish legal expert with a long-standing interest in Plato’s Atlantis. He is the author of El naufrago del Julán [1734], which is a novel that explores the history of the Canaries and the origins of its Guanche inhabitants. His grandfather published a book in 1922 which investigates the geology of the Canaries. His father, also Alfonso d’Ascanio, was also preparing to finish a book in the late 1950’s(a), which was intended to demonstrate that Atlantis had been situated in the Atlantic, where its remnants are now the Macaronesian groups of islands (Canaries, Azores, Madeira & Cape Verde). D’Ascanio snr also contributed to Egerton Sykes‘ Atlantis magazine.

(a) Atlantis, Vol.12, No.1, Nov/Dec 1958

Landbridges

Landbridges, in biogeography, are described by Wikipedia as “an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea levels fall, exposing shallow, previously submerged sections of continental shelf; or when new land is created by plate tectonics; or occasionally when the sea floor rises due to post-glacial rebound after an ice age.”

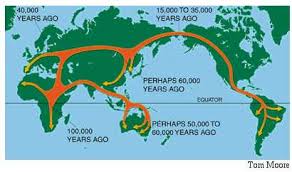

In the distant past, landbridges are believed to have played a critical part in early human migration. Similarly,  landbridges, both real and speculative are important components in many Atlantis theories. There is no doubt that the ending of the last Ice Age and the consequent rising sea levels led to the creation of islands where continuous land has previously existed. The separation of Ireland and Britain from each other and from mainland Europe is just one example, the latter leading to a number of writers identifying ‘Doggerland‘, which lay between Britain and Denmark as the home of Atlantis.

landbridges, both real and speculative are important components in many Atlantis theories. There is no doubt that the ending of the last Ice Age and the consequent rising sea levels led to the creation of islands where continuous land has previously existed. The separation of Ireland and Britain from each other and from mainland Europe is just one example, the latter leading to a number of writers identifying ‘Doggerland‘, which lay between Britain and Denmark as the home of Atlantis.

>The two most discussed landbridges were at the Bering Strait, where it is thought that it provided the gateway for humans to enter the Americas from Asia and an Atlantic landbridge, which was proposed as early as the 17th century when Francois Placet, a French abbot, who, in 1668, wrote “The break up of large and small world’s, as being demonstrated that America was connected before the flood with the other parts of the world.” A Scientific American article relates how “He argued that the two continents were once connected by the lost continent of “Atlantis” and the flood of the bible separated them.” (d)<

Later by John B. Newman in 1849 [488.8], who wrote that “in former times an island of enormous dimensions, named Atlantis, stretched from the north-western coast of Africa across the Atlantic ocean and that over this continental tract both man and beast migrated westward.“

>Charles Frédéric Martins was a French botanist and geologist who was so intrigued by the similarity of geology as well as plant species on the Azores, Spain and Ireland that he suggested in his 1866 book, Du Spitzberg Au Sahara [1440],that these were physically linked in the distant past and that they may have been part of Atlantis(c).

Martins also said, in the Revue des Deux Mondes for March 1, 1867, “Now, hydrography, geology, and botany agree in teaching us that the Azores, the Canaries, and Madeira are the remains of a great continent which formerly united Europe to North America.”<

The Atlantic landbridge idea became quite popular by the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries and even as late as the 1970s when espoused by Rene Malaise(a), but is now completely abandoned. Ignatius Donnelly referred to such a landbridge as a ‘connecting plateau’ linking Europe, Africa and America that allowed plants and animals to cross in both directions.

Although there was only one suggestion that the Bering Strait was in any way connected with Plato’s Atlantis, several commentators identified an Atlantic landbridge as the ideal location for Plato’s Atlantis, particularly as he placed it in the Atlantic Sea. However, this should not be confused with the Atlantic Ocean, a word that had an entirely different meaning for the ancient Greeks.

The idea was initially put forward in order to explain the floral and faunal similarities shared by the Old World and the New World of the Americas. The hypothetical Atlantic landbridges or a series of steppingstone islands. also offered possible routes for the peopling of the Americas by Europeans and/or Africans. It was not long before the discovery of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge(b) seemed to confirm this idea. Then it was suggested that Atlantis existed on this landbridge, which was destroyed by rising sea levels after the last Ice Age, leaving just the Azores, Madeira and a few other islands as remnants.

A number of landbridges have been proposed for the Mediterranean and linked to a variety of Atlantis theories, the most notable being proposed for the straits of Gibraltar, Sicily, Messina and Bonifacio. Although it is evident that landbridges existed at most of these locations, to associate them with any particular Atlantis theory requires that the date of their existence is compatible with Plato’s narrative.

Less popular theories have been constructed involving landbridges in locations, such as the Caribbean and Indonesia.

(a) Atlantis, Vol.27, No.1, Jan-Feb 1974.

(b) From the Contracting Earth to early Supercontinents – Scientific American Blog Network

Mille, Pierre

Pierre Mille (1864-1941) was a noted French journalist. In the 1920’s Mille declared(a) that the argan tree, which grows in Morocco, Madeira and Azores was the last survivor of Plato’s Atlantis. He was an honorary member of Paul le Cour’s Atlantis Association.

Pierre Mille (1864-1941) was a noted French journalist. In the 1920’s Mille declared(a) that the argan tree, which grows in Morocco, Madeira and Azores was the last survivor of Plato’s Atlantis. He was an honorary member of Paul le Cour’s Atlantis Association.

The fruit of the argan tree was claimed by Michael Hübner to have been the ‘golden apples’ sought by Hercules in the Garden of the Hesperides.

Viera y Clavijo, José

José Viera y Clavijo (1731-1813) was a Catholic priest and considered to be one of the most outstanding Canarians of his day, who proposed in 1772/3[1274] in a four-volume work on the history of the Canaries that the archipelago together with the Azores and Madeira were remnants of Atlantis, more than a century before Ignatius Donnelly advocated similar ideas.

José Viera y Clavijo (1731-1813) was a Catholic priest and considered to be one of the most outstanding Canarians of his day, who proposed in 1772/3[1274] in a four-volume work on the history of the Canaries that the archipelago together with the Azores and Madeira were remnants of Atlantis, more than a century before Ignatius Donnelly advocated similar ideas.

Odysseus & Herakles

Odysseus and Herakles are two of the best-known heroes in Greek mythology, both of whom had one important common experience, they each had to endure a series of twelve tests. However, although different versions of the narratives are to be found with understandable variations in detail, the two stories remain substantially the same.

The two tales have been generally interpreted geographically although a minority view is that an astronomical/astrological interpretation was intended, as the use of twelve events in both accounts would seem to point to a connection with the zodiac!

Alice A. Bailey is probably the best known regarding Hercules in her book The Labours of Hercules[1163], while Kenneth & Florence Wood have also proposed Homer’s work as a repository of astronomical data[0391]. Bailey’s work is available as a pdf file(d).

In geographical terms, Herakles and Odysseus share something rather intriguing. Nearly all of the ‘labours’ of Herakles (Peisander c 640 BC) and all of the ‘trials’ of Odysseus (Homer c.850 BC) are generally accepted to have taken place in the eastern Mediterranean. In fact, the first map of the geography of the Odyssey, was produced by Ortelius in 1597, which situated all of the locations in the central and eastern Mediterranean(e).

However, in both accounts, there is a suggestion that they experienced at least one of their adventures in the extreme western Mediterranean, at what many consider to be the (only) location of the Pillars of Heracles as defined by Eratosthenes centuries later (c.200 BC). Significantly, nothing happens over the 1100-mile (1750 km) journey on the way there and nothing occurs on the way back!

I think it odd that both share this same single, apparently anomalous location. I suggest that we should consider the possibility that the accounts of Heracles and Odysseus are possibly distorted versions of each other and that, in the later accounts of their exploits, the use of the extreme western location for the trial/labour is possibly only manifestation of a blind acceptance of the geographical claims of Eratosthenes or a biased view that this was always the case. A credible geographical revision of the location of those inconsistent activities by Odysseus and Heracles to somewhere other than the Gibraltar region would add weight to those, such as myself, that consider a Central Mediterranean location for the ‘Pillars’ more likely.

Philipp Clüver spent some years surveying Italy and Sicily and concluded in his Sicilia Antiqua (1619) that the Homeric locations associated with the travels of Odysseus were to be found in Italy and Sicily(g) and that Homer identified Calypso’s Island (Ogygia) as Malta.

>The University of Buffalo website offers a number of maps associated with a variety of theories relating to elements found in Homer’s epic poems(i).<

The German historian, Armin Wolf, relates how his research over 40 years unearthed 80 theories on the geography of the Odyssey, of which around 30 were accompanied by maps. In 2009, he published, Homers Reise: Auf den Spuren des Odysseus[0669], a German language book that expands on the subject, concluding that all the wandering of Odysseus took place in the central and eastern Mediterranean. In a fascinating paper(a) he reviews many of these theories and offers his own ideas on the subject along with his own proposed maps, which exclude the western Mediterranean entirely. Wolfgang Geisthövel adopted Wolf’s conclusions in Homer’s Mediterranean [1578].

With regard to Hercules, the anomalous nature of the ‘traditional’ location of Erytheia for his 10th ‘labour’ is evident on a map(b), while the 11th could be anywhere in North Africa.

Further study of the two narratives might offer further strong evidence for a central Mediterranean location for the ‘Pillars’ around the time of Solon! For example, “map mistress” places Erytheia in the vicinity of Sicily(c), while my personal choice would be the Egadi Islands further to the north, Egadi being a cognate of Gades, frequently linked with Erytheia.

There is also a school of thought which suggests that most of Odysseus’ wanderings took place in the Black Sea. Anatoliy Zolotukhin, is a leading exponent of this idea(f).

>Wikipedia touched on the even more controversial suggestion that Odysseus had travelled in the Atlantic – “Strabo‘s opinion that Calypso’s island and Scheria were imagined by the poet as being ‘in the Atlantic Ocean’ has had significant influence on modern theorists. Henriette Mertz, a 20th-century author, argued that Circe’s island is Madeira, Calypso’s island one of the Azores, and the intervening travels record a discovery of North America: Scylla and Charybdis are in the Bay of Fundy, Scheria in the Caribbean.” (h)<

(a) https://authorzilla.com/9AbvV/armin-wolf-mapping-homer-39-s-odyssey-research-notebooks.html (link broken) *

(b) https://www.igreekmythology.com/Hercules-map-of-labors.html

(c) Pantelleria & Erytheia: Southwest Sicily Sunken Coastline to Tunisia (archive.org)

(d) https://www.bailey.it/files/Labours-of-Hercules.pdf

(e) https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/geography-odyssey

(f) https://homerandatlantis.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Scylla-CharybdisJAH-1.pdf

(g) https://journals.openedition.org/etudesanciennes/906

(h) Geography of the Odyssey – Wikipedia *

(i) INDICES (buffalo.edu) *

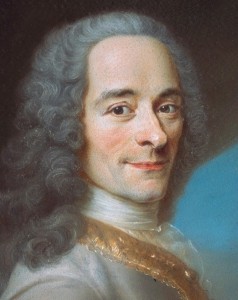

Voltaire

Voltaire (1694-1778) was the nom de plume of François-Marie Arouet, who was  a prominent French philosopher and a prolific writer on a wide range of subjects with an estimated output of more than 2,000 books and pamphlets and 20,000 letters.

a prominent French philosopher and a prolific writer on a wide range of subjects with an estimated output of more than 2,000 books and pamphlets and 20,000 letters.

Jean Sylvain Bailly wrote a series of letters addressed to Voltaire on the subject of Atlantis, an English translation of which has been published by the British Library[926] .

However, it appears that Voltaire was somewhat sceptical about the existence of Atlantis remarking in Essai sur le moeurs[1504] that “ if it were true that such a part of the world ever existed. Most likely it was none other than the island of Madeira.”

Anyone researching Atlantis might be advised to remember Voltaire’s aphorism which states that while “doubt is not a pleasant mental state, certainty is an absurd one.”

Lamas, Maria

Almeida, João de

João de Almeida (1873-1953) was a Portuguese military officer who held the  final rank of General. In 1901 he wrote his undergraduate thesis on the subject of Atlantis, which he published[1474] in 1931 as O Espírito da Raça Portuguesa na sua Expansão Além-Mar(a), where he identified the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores, Madeiras and Canaries as the remnants of Atlantis. He included two hypothetical maps showing Atlantis as a very large landmass extending westward from mainland of Europe and North Africa and incorporating those three archipelagos as well as the British Isles.

final rank of General. In 1901 he wrote his undergraduate thesis on the subject of Atlantis, which he published[1474] in 1931 as O Espírito da Raça Portuguesa na sua Expansão Além-Mar(a), where he identified the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores, Madeiras and Canaries as the remnants of Atlantis. He included two hypothetical maps showing Atlantis as a very large landmass extending westward from mainland of Europe and North Africa and incorporating those three archipelagos as well as the British Isles.

He returned to the subject of Atlantis again in 1950[1475] with a supplement in 1951[1476].

(a) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20180402094912/https://www.nova-acropole.pt/a_misterio%20atlante.html (Portuguese)

Pereira de Sousa, Francisco Luís

Francisco Luís Pereira de Sousa (1870-1931) was born in Funchal, the capital of the mid-Atlantic Portuguese archipelago of Madeira. He was a geologist by profession and is well known for his 1914 study of the devastating Lisbon earthquake of 1755. He speculated(a) that this tragic event might have been the last ‘gasp’ of a sunken Atlantis. He also suggested that Atlantis had originally occupied most of the Atlantic, linking Africa, Europe and America. He considered the Canaries and his native Madeira to be present-day remnants of Plato’s island.

Francisco Luís Pereira de Sousa (1870-1931) was born in Funchal, the capital of the mid-Atlantic Portuguese archipelago of Madeira. He was a geologist by profession and is well known for his 1914 study of the devastating Lisbon earthquake of 1755. He speculated(a) that this tragic event might have been the last ‘gasp’ of a sunken Atlantis. He also suggested that Atlantis had originally occupied most of the Atlantic, linking Africa, Europe and America. He considered the Canaries and his native Madeira to be present-day remnants of Plato’s island.

(a) https://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/artigo5081.doc

Hodge, Bodie

Bodie Hodge is a Christian fundamentalist writer with The Museum of Creation in Kentucky and its propaganda wing Answers in Genesis(a). In March 2010 he raised a few eyebrows when he ventured to discuss the existence of Plato’s Atlantis and its compatibility with the Bible(b). He concluded that if it had existed, it had been located in the Atlantic with its remnants being the Azores, Madeira or the Canaries. He also calculated its demise to have occurred between 1818 BC and 600 BC.

Bodie Hodge is a Christian fundamentalist writer with The Museum of Creation in Kentucky and its propaganda wing Answers in Genesis(a). In March 2010 he raised a few eyebrows when he ventured to discuss the existence of Plato’s Atlantis and its compatibility with the Bible(b). He concluded that if it had existed, it had been located in the Atlantic with its remnants being the Azores, Madeira or the Canaries. He also calculated its demise to have occurred between 1818 BC and 600 BC.

> “Atlantis, if the reports had been reasonably correct, would have been destroyed, leaving only much smaller islands lying above the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. The most logical remains seem to be the Canary or Madeira Islands, as well as other underwater islands close to them that may have been largely destroyed about 3000 years ago.“(d)<

A rather harsh review of Hodge’s output is to be found on the RationalWiki website(c).

(a) https://www.answersingenesis.org/

(b) https://answersingenesis.org/the-flood/did-atlantis-exist/

(c) https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Bodie_Hodge

(d) Creationism and Atlantis – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog) *