Odysseus

Laestrygonians

Laestrygonians, we are told by Homer were mythical giants encountered by Odysseus on his return journey to Ithaca.

Wikipedia tells us that “according to Thucydides (6.2.1.) and Polybius (1.2.9) the Laestrygones inhabited southeast Sicily. The name is akin to that of the Lestriconi, a branch of the Corsi people of the northeast coast of Sardinia (now Gallura). Later Greeks believed that the Laestrygonians, as well as the Cyclopes, had once inhabited Sicily.

“According to historian Angelo Paratico, the Laestrygonians were the result of a legend originated by the sight by Greek sailors of the Giants of Mont’e Prama, recently excavated in Sardinia. Earlier, Victor Bérard had also suggested Sardinia.

Some writers have also sought to attribute a historical reality to the Laestrygonians, often proposing locations very different to that of Thucydides and Polybius. Emmet Sweeney [700.23] has noted that Robert Graves who invariably placed the Greek myths in a Mediterranean setting, suggested that the home of the Laestrygonians was to be found in the far north of Europe, in the Land of the Midnight Sun!

Equally exotic is the suggestion from Gerard W.J. Janssen of Leiden University who places the voyages of Odysseus in the Atlantic(b). However, although he situates most of the places visited in the eastern Atlantic, he does claim(a) that Homer‘s Laestrygonians were to be found in Cuba, an interpretation supported by both Théophile Cailleux and Iman Wilkens.

(a) LAISTRUGONIACUBA, LA HAVANA (homerusodyssee.nl)

(b) https://www.academia.edu/38535990/ATLANTIC_OGUGIA_AND_KALUPSO?email_work_card=view-paper

Greek Colonisation *

Greek Colonisation is something of misnomer on two counts. First of all is the fact that there was no unified Greek state until the time of Alexander the Great. Instead the territory was fragmented into a number of competing city- states (poleis) that formed shifting alliances to meet the exigencies of the day.

Secondly, the term ‘colonisation’ did not mean the same then as it does today. Individual city states had their own expansion ambitions, which were generally concerned with trade rather than  territory. It seems that most of the colonies began as trading posts, known as emporia(a), some developing into towns, others grew into urban centres and even established colonies of their own.

territory. It seems that most of the colonies began as trading posts, known as emporia(a), some developing into towns, others grew into urban centres and even established colonies of their own.

In the first millennium BC, some of the Greek city-states gradually expanded their influence(c) eastward into Asia Minor and the Black Sea and westward along the northern coast of the Mediterranean, eventually founding Massalia (modern Marseilles), which established emporia in eastern Spain.

Some writers, such as Henriette Mertz, have proposed that the ancient Greeks travelled as far as America and that Homer’s story of Odysseus was a retelling of such a voyage(k). More recently, Minas Tsikritsis has claimed that the Greeks had contact with North America, at least as far back as 86 AD!(d) Some time later he expanded on the idea in a paper published on the Researchgate website(e). Manolis Koutlis went further in his book, In the Shadow: The Greek Colonies of North America and the Atlantic 1500 BC -1500 AD [1617].

Even more extreme is the odd claim by Lonko Kilapan that ancient Greeks colonists settled in Chile and whose descendants are known now as Mapuche and earlier as Araucans or Araucanians(f) . Michael Issigonis has championed the idea of early Greeks in South America and elsewhere on the Academia.edu website(g)(h).

Tara MacIsaac published an article(i) supporting this idea of ancient Greeks in South America, apparently influenced by Enrico Mattievich and earlier comments by José Imbelloni.

The greek-thesaurus.gr website offers three pages of images of artefacts found in the Americas that can be interpreted as evidence of ancient Greek influence in the region(j). The compiler claims that “If these pictures are not proofs for the existence of the ancient Greeks in America the word “proof” has lost it’s meaning.”

The Phoenicians had their own city-states such a Tyre, Sidon and Byblos. They established ‘colonies along north Africa, and Spain. They competed with the Greeks, particularly in the central Mediterranean, where at one point they shared Sicily. Settlers from Tyre founded Carthage, which in turn became more powerful than and independent of its parent city and became more belligerent, eventually engaging in a series of wars with Rome, which it lost.

There is much more relevant information to be found on the excellent Ancient History Encyclopedia website(b) .

(a) https://www.academia.edu/1505105/The_origins_of_Greek_colonisation_and_Greek_polis_some_observations

(b) https://www.ancient.eu/edu/

(c) https://www.ancient.eu/Greek_Colonization/

(e) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321319687/download

(f) THE UNKNOWN HELLENIC COLONIZATION.THE CASE OF THE ARAUCANS OF CHILE (archive.org) *

(g) https://www.academia.edu/9066795/Did_the_Mapuche_of_Chile_travel_from_Homeric_Age_Greece

(h) https://www.academia.edu/32921347/ANCIENT_GREEKS_TRAVELLED_WORLDWIDE

(j) https://www.greek-thesaurus.gr/Ancient-Greeks-existence-America.html

Koutlis, Manolis *

Manolis Koutlis is a computer engineer and the author of In the Shadow: The Greek Colonies of North  America and the Atlantic 1500 BC -1500 AD[1617], in which he seeks to demonstrate that the Greeks had settlements in North America. Using the classical texts of Plutarch, Homer, Hesiod and Plato as well as the traditions of the Native Americans of the North East, he offers evidence to support his thesis.

America and the Atlantic 1500 BC -1500 AD[1617], in which he seeks to demonstrate that the Greeks had settlements in North America. Using the classical texts of Plutarch, Homer, Hesiod and Plato as well as the traditions of the Native Americans of the North East, he offers evidence to support his thesis.

The idea of ancient Greeks in Canada has been around for some time with Henriette Mertz in the 1960’s suggesting that Odysseus’ wanderings took place in the Atlantic and that he was the first European to visit America.

Koutlis has concluded that Ogygia was located on St. Paul Island in the Cabot Strait and goes further, locating Atlantis in the Gulf of St. Lawrence northeast of the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island, not far from Quebec’s Magdalen Islands.

A few years earlier, Emilio Spedicato, also proposed that the region around the Mouth of the St. Lawrence River, in Canada, had been visited by ancient Greeks. His comments were addressed to the 2005 Atlantis Conference [629.411]. He did not, however, suggest a Canadian location for Atlantis as he had already claimed Hispaniola as its home.

The first 37 pages of his book can be read online(a)(b)*.

Also See: Minas Tsikritsis, Lucio Russo

(a) https://enskia.com/pdf/In-the-Shadow-sample-1.0.pdf (link broken) *

Odysseus & Herakles

Odysseus and Herakles are two of the best-known heroes in Greek mythology, both of whom had one important common experience, they each had to endure a series of twelve tests. However, although different versions of the narratives are to be found with understandable variations in detail, the two stories remain substantially the same.

The two tales have been generally interpreted geographically although a minority view is that an astronomical/astrological interpretation was intended, as the use of twelve events in both accounts would seem to point to a connection with the zodiac!

Alice A. Bailey is probably the best known regarding Hercules in her book The Labours of Hercules[1163], while Kenneth & Florence Wood have also proposed Homer’s work as a repository of astronomical data[0391]. Bailey’s work is available as a pdf file(d).

In geographical terms, Herakles and Odysseus share something rather intriguing. Nearly all of the ‘labours’ of Herakles (Peisander c 640 BC) and all of the ‘trials’ of Odysseus (Homer c.850 BC) are generally accepted to have taken place in the eastern Mediterranean. In fact, the first map of the geography of the Odyssey, was produced by Ortelius in 1597, which situated all of the locations in the central and eastern Mediterranean(e).

However, in both accounts, there is a suggestion that they experienced at least one of their adventures in the extreme western Mediterranean, at what many consider to be the (only) location of the Pillars of Heracles as defined by Eratosthenes centuries later (c.200 BC). Significantly, nothing happens over the 1100-mile (1750 km) journey on the way there and nothing occurs on the way back!

I think it odd that both share this same single, apparently anomalous location. I suggest that we should consider the possibility that the accounts of Heracles and Odysseus are possibly distorted versions of each other and that, in the later accounts of their exploits, the use of the extreme western location for the trial/labour is possibly only manifestation of a blind acceptance of the geographical claims of Eratosthenes or a biased view that this was always the case. A credible geographical revision of the location of those inconsistent activities by Odysseus and Heracles to somewhere other than the Gibraltar region would add weight to those, such as myself, that consider a Central Mediterranean location for the ‘Pillars’ more likely.

Philipp Clüver spent some years surveying Italy and Sicily and concluded in his Sicilia Antiqua (1619) that the Homeric locations associated with the travels of Odysseus were to be found in Italy and Sicily(g) and that Homer identified Calypso’s Island (Ogygia) as Malta.

>The University of Buffalo website offers a number of maps associated with a variety of theories relating to elements found in Homer’s epic poems(i).<

The German historian, Armin Wolf, relates how his research over 40 years unearthed 80 theories on the geography of the Odyssey, of which around 30 were accompanied by maps. In 2009, he published, Homers Reise: Auf den Spuren des Odysseus[0669], a German language book that expands on the subject, concluding that all the wandering of Odysseus took place in the central and eastern Mediterranean. In a fascinating paper(a) he reviews many of these theories and offers his own ideas on the subject along with his own proposed maps, which exclude the western Mediterranean entirely. Wolfgang Geisthövel adopted Wolf’s conclusions in Homer’s Mediterranean [1578].

With regard to Hercules, the anomalous nature of the ‘traditional’ location of Erytheia for his 10th ‘labour’ is evident on a map(b), while the 11th could be anywhere in North Africa.

Further study of the two narratives might offer further strong evidence for a central Mediterranean location for the ‘Pillars’ around the time of Solon! For example, “map mistress” places Erytheia in the vicinity of Sicily(c), while my personal choice would be the Egadi Islands further to the north, Egadi being a cognate of Gades, frequently linked with Erytheia.

There is also a school of thought which suggests that most of Odysseus’ wanderings took place in the Black Sea. Anatoliy Zolotukhin, is a leading exponent of this idea(f).

>Wikipedia touched on the even more controversial suggestion that Odysseus had travelled in the Atlantic – “Strabo‘s opinion that Calypso’s island and Scheria were imagined by the poet as being ‘in the Atlantic Ocean’ has had significant influence on modern theorists. Henriette Mertz, a 20th-century author, argued that Circe’s island is Madeira, Calypso’s island one of the Azores, and the intervening travels record a discovery of North America: Scylla and Charybdis are in the Bay of Fundy, Scheria in the Caribbean.” (h)<

(a) https://authorzilla.com/9AbvV/armin-wolf-mapping-homer-39-s-odyssey-research-notebooks.html (link broken) *

(b) https://www.igreekmythology.com/Hercules-map-of-labors.html

(c) Pantelleria & Erytheia: Southwest Sicily Sunken Coastline to Tunisia (archive.org)

(d) https://www.bailey.it/files/Labours-of-Hercules.pdf

(e) https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/geography-odyssey

(f) https://homerandatlantis.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Scylla-CharybdisJAH-1.pdf

(g) https://journals.openedition.org/etudesanciennes/906

(h) Geography of the Odyssey – Wikipedia *

(i) INDICES (buffalo.edu) *

Trojan War

The Trojan War, at first sight, may appear to have little to do with the story of Atlantis except that some recent commentators have endeavoured to claim that the war with Atlantis was just a retelling of the Trojan War. The leading proponent of the idea is Eberhard Zangger in his 1992 book The Flood from Heaven [483] and later in a paper(l) published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology. He also argues that survivors of the War became the Sea Peoples, while Frank Joseph contends that the conflict between the Egyptians and the Sea Peoples was part of the Trojan War [108.11].

In an article on the Atlantisforschung website reviewing Zangger’s theory the following paragraph is offered – “What similarities did the Trojan War and the war between Greece and Atlantis have? In both cases, the individual kingdoms in Greece formed a unified army. According to Homer, Greek ships went to the Trojan War in 1186 – according to Plato, Atlantis ruled over 1200 ships. The contingents and weapons are identical (archer, javelin thrower, discus thrower, chariot, bronze weapon, shield). The decisive battle took place overseas on both occasions. In a long period of siege came plague and betrayal. (There is not a word in Plato about a siege or epidemics and treason, dV) In both cases, Greece won the victory. After the Greek forces withdrew, earthquakes and floods struck Greece.“(t)

Steven Sora asserts that the Atlantean war recorded by Plato is a distortion of the Trojan War and contentiously claims that Troy was located on the Iberian Peninsula rather than the more generally accepted Hissarlik in Turkey. Another radical claim is that Troy had been located in Bosnia-Herzegovina or adjacent Croatia, the former by Roberto Salinas Price in 1985[1544], while more recently the latter is promoted by Vedran Sinožic[1543].

Others have located the War in the North Sea or the Baltic. Of these, Iman Wilkens is arguably the best-known advocate of an English location for Troy since 1990. In 2018, Gerard Janssen added further support for Wilkens’ theory(k).

In Where Troy Once Stood [610.18] Wilkens briefly referred to the earliest doubts expressed regarding the location of the Trojan War, starting in 1790 with J.C. Wernsdorf and followed a few years later in 1804 by M. H. Vosz. Then in 1806, Charles deGrave opted for Western Europe. However, it was probably Théophile Cailleux, a Belgian lawyer, whose detailed study of Homeric geography made the greatest inroads into the conventionally accepted Turkish location for Troy. Andreas Pääbo, who contends that the Odyssey and the Iliad had been written by two different authors, proposed that the inspiration for much of the Trojan War came from ancient Lycia. His paper proposes“that Homer had been a military official in an invasion in his time of a location, also with a citadel, further south on the coast, at what is now southwest Turkey, which was ancient Lycia. Proof of this lies within the Iliad itself, in the author’s many references to Lycia, and in particular to using an alternative name for Scamander – Xanthos – which is the river in Lycia around which the original Lycian civilization developed. This paper(u) studies the details given in the Iliad with geographical information about the location of ancient Lycia to prove this case.”

However. controversy has surrounded various aspects of the War since the earliest times. Strabo(a) tells us that Aristotle dismissed the matter of the Achaean wall as an invention, a matter that is treated at length by Classics Professor Timothy W. Boyd(b). In fact, the entire account has been the subject of continual criticism. A more nuanced approach to the reality or otherwise of the ‘War’ is offered by Petros Koutoupis(j).

The reality of the Trojan War as related by Homer has been debated for well over a century. There is a view that much of what he wrote was fictional, but that the ancient Greeks accepted this, but at the same time, they possessed a historical account of the war that varied considerably from Homer’s account(f).

Over 130 quotations from the Illiad and Odyssey have been identified in Plato’s writings, suggesting the possibility of him having adopted some of Homer’s nautical data, which may account for Plato’s Atlantean fleet having 1200 ships which might have been a rounding up of Homer’s 1186 ships in the Achaean fleet and an expression of the ultimate in sea power at that time!

Like so many other early historical events, the Trojan War has also generated its fair share of nutty ideas, such as Hans-Peny Hirmenech’s wild suggestion that the rows of standing stones at Carnac marked the tombs of Atlantean soldiers who fought in the Trojan War! Arthur Louis Joquel II proposed that the War was fought between two groups of refugees from the Gobi desert, while Jacques de Mahieu maintained that refugees from Troy fled to America after the War where they are now identified as the Olmecs! In November 2017, an Italian naval archaeologist, Francesco Tiboni, claimed(h). that the Trojan Horse was in reality a ship. This is blamed on the mistranslation of one word in Homer.

In August 2021 it was claimed that remnants of the Trojan Horse had been found. While excavating at the Hisarlik site of Troy, Turkish archaeologists discovered dozens of planks as well as beams up to 15-metre-long.

“The two archaeologists leading the excavation, Boston University professors Christine Morris and Chris Wilson, say that they have a “high level of confidence” that the structure is indeed linked to the legendary horse. They say that all the tests performed up to now have only confirmed their theory.”(o)

“The carbon dating tests and other analyses have all suggested that the wooden pieces and other artefacts date from the 12th or 11th centuries B.C.,” says Professor Morris. “This matches the dates cited for the Trojan War, by many ancient historians like Eratosthenes or Proclus. The assembly of the work also matches the description made by many sources. I don’t want to sound overconfident, but I’m pretty certain that we found the real thing!”

It was not a complete surprise when a few days later Jason Colavito revealed that the story was just a recycled 2014 hoax, which “seven years later, The Greek Reporter picked up the story from a Greek-language website. From there, the Jerusalem Post and International Business Times, both of which have large sections devoted to lightly rewritten clickbait, repeated the story nearly verbatim without checking the facts.”(p)

Various attempts have been made to determine the exact date of the ten-year war, using astronomical dating relating to eclipses noted by Homer. In the 1920s, astronomers Carl Schoch and Paul Neugebauer put the sack of Troy at close to 1190 BC. According to Eratosthenes, the conflict lasted from 1193 to 1184 BC(m).

In 1956, astronomer Michal Kamienski entered the fray with the suggestion that the Trojan War ended circa 1165 BC, suggesting that it may have coincided with the appearance of Halley’s Comet!(n)

An interesting side issue was recorded by Isocrates, who noted that “while they with the combined strength of Hellas found it difficult to take Troy after a siege which lasted ten years, he, on the other hand, in less than as many days, and with a small expedition, easily took the city by storm. After this, he put to death to a man all the princes of the tribes who dwelt along the shores of both continents; and these he could never have destroyed had he not first conquered their armies. When he had done these things, he set up the Pillars of Heracles, as they are called, to be a trophy of victory over the barbarians, a monument to his own valor and the perils he had surmounted, and to mark the bounds of the territory of the Hellenes.” (To Philip. 5.112) This reinforced the idea that there had been more than one location for the Pillars of Herakles(w).

In the 1920s, astronomers Carl Schoch and Paul Neugebauer put the sack of Troy at close to 1190 BC.(q)

In 2008, Constantino Baikouzis and Marcelo O. Magnasco proposed 1178 BC as the date of the eclipse that coincided with the return of Odysseus, ten years after the War(a). Stuart L. Harris published a paper on the Migration & Diffusion website in 2017(g), in which he endorsed the 1190 BC date for the end of the Trojan War.

Nikos Kokkinos, one of Peter James’ co-authors of Centuries of Darkness, published a paper in 2009 questioning the accepted date for the ending of the Trojan War of 1183 BC,(r) put forward by Eratosthenes.

New dating of the end of the Trojan War has been presented by Stavros Papamarinopoulos et al. in a paper(c) now available on the Academia.edu website. Working with astronomical data relating to eclipses in the 2nd millennium BC, they have calculated the ending of the War to have taken place in 1218 BC and Odysseus’ return in 1207 BC.

A 2012 paper by Göran Henriksson also used eclipse data to date that war(v).

What is noteworthy is that virtually all the recent studies of the eclipse data are in agreement that the Trojan War ended near the end of the 13th century BC, which in turn can be linked to archaeological evidence at the Hissarlik site. Perhaps even more important is the 1218 BC date for the Trojan War recorded on the Parian Marble, reinforcing the Papamarinoupolos date.

A 2012 paper by Rodger C. Young & Andrew E. Steinmann added further support for the 1218 BC Trojan War date(s),>>also coinciding with the chronology of the Parian Marble.<<

Eric Cline has suggested that an earlier date is a possibility, as “scholars are now agreed that even within Homer’s Iliad there are accounts of warriors and events from centuries predating the traditional setting of the Trojan War in 1250 BC” [1005.40]. Cline had previously published The Trojan War: A very Short Introduction [2074], which was enthusiastically reviewed by Petros Koutoupis, who ended with the comment that “It is difficult to believe that such a large amount of detail could be summarized into such a small volume, but Cline is successful in his efforts and provides the reader with a single and concise publication around Homer’s timeless epic.” (x)

However, an even more radical redating has been strongly advocated by a number of commentators(d)(e) and not without good reason.

(a)Geographica XIII.1.36

(b) https://journal.oraltradition.org/wp-content/uploads/files/articles/10i/12_boyd.pdf *

(c) https://www.academia.edu/7806255/A_NEW_ASTRONOMICAL_DATING_OF_THE_TROJAN_WARS_END

(d) Archive 2401

(e) https://www.varchive.org/schorr/troy.htm

(f) https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2011/09/06/the-trojan-war-in-greek-historical-sources/

(g) https://www.migration-diffusion.info/article.php?year=2017&id=509

(j) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/was-there-ever-trojan-war-001737

(k) https://www.homerusodyssee.nl/id12.htm

(l) https://www.academia.edu/25590584/Plato_s_Atlantis_Account_A_Distorted_Recollection_of_the_Trojan_War

(m) Eratosthenes and the Trojan War | Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (archive.org)

(n) Atlantis, Volume 10 No. 3, March 1957

(o) https://greekreporter.com/2021/08/10/archaeologists-discover-trojan-horse-in-turkey/

(p) Newsletter Vol. 19 • Issue 7 • August 15, 2021

(q) https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna25337041

(r) https://www.centuries.co.uk/2009-ancient%20chronography-kokkinos.pdf

(t) Troy – Zangger’s Atlantis – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(v) https://www.academia.edu/39943416/THE_TROJAN_WAR_DATED_BY_TWO_SOLAR_ECLIPSES

(w) https://greekreporter.com/2023/05/25/pillars-hercules-greek-mythology/

(x) Book Review – The Trojan War: A Very Short Introduction by Eric H. Cline (substack.com)

MacRae, Michael

Michael MacRae (1949- ) is an Australian artist, writer and documentary maker who specialises in comparative mythology. His 2014 book, Sun Boat:The Odyssey Deciphered[985]offers the theory that Homer’s epic poem is an account of Odysseus’ circumnavigation of the world circa 1160-1130 BC.

In June 2015 he was ‘the author of the month’ on Graham Hancock’s website(a) with an article promoting his book. However, Jason Colavito has responded to that with a dismissive critique of MacRae’s idea(b).

This tussle has continued back and forth on Hancock’s website(c).

MacRae notes the suggestion that Homer’s Scheria can be identified with Atlantis and as such was probably situated off the western end of the Bay of Cadiz, Portugal’s Cape Vincent.

(a) https://www.grahamhancock.com/forum/MacRaeM1.php

(c) https://www.grahamhancock.com/phorum/read.php?f=8&i=35955&t=35950

Clüver, Philipp (Philippi Cluverii)

Philipp Clüver (Philippi Cluverii) (1580-1622) was a Polish geographer and historian. In his Introductio in Universam Geographiam [1092] which was published posthumously from 1624 on, he considered Atlantis to have been an island in the Atlantic and had been a stepping stone to America. A 1711 edition of his book is available online(a).

Philipp Clüver (Philippi Cluverii) (1580-1622) was a Polish geographer and historian. In his Introductio in Universam Geographiam [1092] which was published posthumously from 1624 on, he considered Atlantis to have been an island in the Atlantic and had been a stepping stone to America. A 1711 edition of his book is available online(a).

Clüver spent some years surveying Italy and Sicily and concluded in his Sicilia Antiqua (1619) that the Homeric locations associated with the travels of Odysseus were to be found in Italy and Sicily(b) and that Homer identified Calypso’s Island (Ogygia) as Malta.

(a) https://ia802703.us.archive.org/11/items/phicluvgeo00cluverii/phicluvgeo00cluverii.pdf (Latin)

Steuerwald, Hans (L)

Hans Steuerwald is another unconventional German writer who favours the idea of the capital of Atlantis being located on the Celtic Shelf near Penzance in Cornwall. This he expressed in his 1983 book, Der Untergang von Atlantis (The Fall of Atlantis)[564], in which he also dated its demise to 1240 BC.

He has also supported[565] the idea that Homer’s Odysseus (Roman Ulysses} visited Scotland on his famous travels.

de Meester, E.J.

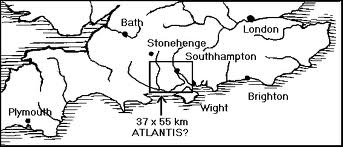

E.J. de Meester is a Dutch researcher who is best known for his support for the controversial theory that Homer’s Odysseus travelled to Ireland and Britain. However, he goes further and argues that Atlantis was located in England, situated just south of Stonehenge on a plain between Salisbury and Chichester.

His website, which was well worth a visit, is now discontinued, but can still be accessed on the archive.org website(a).

>De Meester is critical of Graham Hancock‘s hyperdiffusionist concept of Atlantis commenting that “In 1999 Discovery Channel broadcast a three-part series called ‘Quest for the lost Civilisation’. In it, Graham Hancock stated that the pyramids, Angkor Vat, Stonehenge, the stones of Carnac, the Nazca lines, temples in Mexico and the statues of Easter Island were all part of an ancient global civilisation of seafarers who were apparently obsessed by astrology. The temples of Angkor Vat (in Cambodia) were said to be built in the shape of the zodiac sign Draco, the pyramids of Gizeh in the shape of Sirius; the Sphinx is supposed to be looking at the sign of Leo. It’s all rather vague. Hard to say whether it’s nonsense or not. More information can be found in Hancocks books, like ‘Fingerprints of the Gods’ [0275] and ‘Heaven’s Mirror’ [0855].”<

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20090614050055/https://home-3.tiscali.nl/~meester7/engatlantis.html

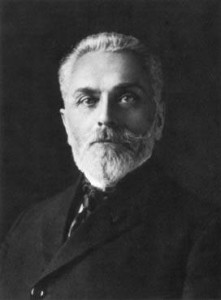

Bérard, Victor

Victor Bérard (1864-1931) the French classical scholar who translated Homer’s Odysseus into French with an introduction by Fernand Robert in later editions.

Victor Bérard (1864-1931) the French classical scholar who translated Homer’s Odysseus into French with an introduction by Fernand Robert in later editions.

He suggested that Homer’s Laestrygonians had been residents in Sardinia.

In the 1920’s[160] he wrote that he favoured Carthage in North Africa as the most probable location for Atlantis.