Robert Fox

Strait of Sicily

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

(i) Both the Strait of Messina to the north, between Sicily and Italy together with the Strait of Sicily to the south remained open.

(ii) The Strait of Messina was closed, joining Sicily to Italy, while the Strait of Sicily remained open.

(iii) Both the Strait of Messina and the Strait of Sicily were closed, providing a land bridge between Tunisia and Italy, separating the Eastern from the Western Mediterranean Basins.

I find it strange that what we call today the Strait of Sicily is 90 miles wide. Now the definition of ‘strait’ is a narrow passage of water connecting two large bodies of water. How 90 miles can be described as ‘narrow’ eludes me. Is it possible that we are dealing with a case of mistaken identity and that the ‘Strait of Sicily’ is in fact the Strait of Messina, which is narrow? Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(a) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(b).

Armin Wolf, the German historian, noted(e) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and was quite possibly referring to that same part of Italy which later became known as ‘Magna Graecia’. Robert Fox in The Inner Sea[1168.141] confirms that this long-standing usage of ‘continent’ refers to Italy.

It is worth pointing out that the Strait of Messina is sometimes referred to in ancient literature as the Pillars of Herakles and designates the sea west of this point as the ‘Atlantic Ocean’. Modern writers such as Sergio Frau and Eberhard Zangger, among others, have pointed out that the term ‘Pillars of Herakles’ was applied to more than one location in the Mediterranean in ancient times.

The Strait of Messina is frequently associated with the story of Scylla & Charybdis, which led Arthur R. Weir in a 1959 article(d) to refer to ancient documents, which state that Scylla & Charybdis lie between the Pillars of Heracles.

In 1910, the celebrated Maltese botanist, John Borg, proposed[1132] that Atlantis had been situated on what is now submerged land between Malta and North Africa. A number of other researchers, such as Axel Hausmann and Alberto Arecchi, have expressed similar ideas.

The Strait of Sicily is home to a number of sunken banks, previously exposed during the Last Ice Age. As levels rose most of these disappeared, an event observed by the inhabitants of the region at that time. The MapMistress website(c) has proposed that one of these banks was the legendary Erytheia, the sunken island of the far west. The ‘far west’ later became the Strait of Gibraltar but for the early Greeks it was the Central Mediterranean.

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(d) Atlantis – A New Theory, Science Fantasy #35, June 1959 pp 89-96 https://drive.google.com/file/d/10JTH401O_ew1fs8uhXR9C5IjNDvqnmft/view

>(e) Wayback Machine (archive.org) See Note 5<

Continent *

The term ‘Continent’, is derived from the Latin terra continens, meaning ‘continuous land’ and in English is relatively new, not coming into use until the Middle English period (11th-16th centuries). Apart from that, it is sometimes used to imply the mainland. The Scottish island of Shetland is known by the smaller islands in the archipelago as Mainland, its old Norse name was Megenland, which means mainland. In turn, the people of Mainland, Shetland, will apply the same title to Britain, who in turn apply the term ‘continuous land’ or continent to mainland Europe. It seems that the term is relative.

The term has been applied arbitrarily by some commentators to Plato’s Atlantis, usually by those locating it in the Atlantic. Plato never called Atlantis a continent, but instead, as the sixteen instances below prove, he consistently referred to it as an island, probably the one containing the capital city of the confederation or alliance!

[Timaeus 24e, 25a, 25d Critias 108e, 113c, 113d, 113e, 114a, 114b, 114e, 115b, 115e, 116a, 117c, 118b, 119c]

Several commentators have assumed that when Plato referred to an ‘opposite continent’ he was referring to the Americas, however, Herodotus, who flourished after Solon and before Plato, was quite clear that there were only three continents known to the Greeks, Europe, Asia and Libya (4.42). In fact, before Herodotus, only two landmasses were considered continents, Europe and Asia, with Libya sometimes considered part of Asia. Furthermore, Anaximander drew a ‘map’ of the known world (left), a century after Herodotus, showing only the three continents, without any hint of territory beyond them.

Nevertheless, there has always been a school of thought that supported the idea of the ancient Greeks having knowledge of the Americas. In 1900, Peter de Roo in History of America before Columbus [890] not only supported this contention but suggested further that ancient travellers from America had travelled to Europe [Vol.1.Chap 5].

Daniela Dueck in her Geography in Classical Antiquity [1749] noted that “Hecataeus of Miletus divided his periodos gês into two books,each devoted to one continent, Europe and Asia, and appended his description of Egypt to the book on Asia. In his time (late sixth century bce), there was accordingly still no defined identity for the third continent. But in the fifth century the three continents were generally recognized, and it became common for geographical compositions in both prose and poetry to devote separate literary units to each continent.”

So when Plato does use the word ‘continent’ [Tim. 24e, 25a, Crit. 111a] we can reasonably conclude that he was referring to one of these landmasses, and more than likely to either Europe or Libya (North Africa) as Atlantis was in the west, ruling out Asia.

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(b) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). It would seem that in this particular circumstance the term ‘Sicilian Strait’ refers to the Strait of Messina, which is another example of how ancient geographical terms often changed their meaning over time (see Atlantic & Pillars of Herakles).

The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(d). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. This would push the custom of referring to Italy as a ‘continent’ back to the time of Plato, who clearly states (Tim. 25a) that the Atlantean alliance “ruled over all the island, over many other islands as well. and over sections of the continent.” (Wells). The next passage recounts their control of territory in Europe and North Africa, so it naturally begs the question as to what was ‘the continent’ referred to previously? I suggest that the context had a specific meaning, which, in the absence of any other candidate and the persistent usage over the following two millennia can be reasonably assumed to have been southern Italy.

Centuries later, the historian, Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) refers at least twice[1523.6.209/10] to the ‘continent of Italy’. More recently, Armin Wolf (1935- ), the German historian, when writing about Scheria relates(a) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” This continuing usage of the term is confirmed by a current travel site(c) and by author, Robert Fox in The Inner Sea [1168.141].

I suggest that Plato similarly used the term and can be seen as offering a more rational explanation for the use of the word ‘continent’ in Timaeus 25a, adding to the idea of Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean.

Giovanni Ugas claims that the Mediterranean coast of southern Spain and France, along with the Italian peninsula constituted the ‘true continent’ (continente vero) referred to by Plato. (see below)

Furthermore, the text informs us that this opposite continent surrounds or encompasses the true ocean, a description that could not be applied to either of the Americas as neither encompasses the Atlantic, which makes any theory of an American Atlantis more than questionable.

Modern geology has definitively demonstrated that no continental mass lies in the Atlantic and quite clearly the Mediterranean does not have room for a sunken continent.

(a) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(b) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(c) Four Ways to Do Sicily – Articles – Departures (archive.org)

(e) The Elusive Location of Atlantis Part 1 – Luciana Cavallaro (archive.org) *

America *

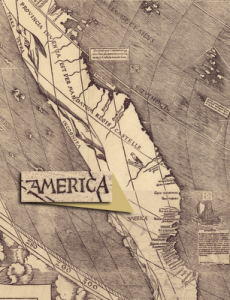

America as the home of Atlantis took off as an idea shortly after its discovery (or perhaps more correctly, rediscovery) by Columbus. Initially, reports sent back to Europe designated America as ‘Paradise’

until its identification as Atlantis quickly took hold. John Dee in the time of Elizabeth I was convinced that the newly discovered Americas were in fact, Atlantis, an idea endorsed by Francis Bacon. The first time that America was so named on a map was on the 1507(c) Waldseemüller map, sometimes referred to as “America’s birth certificate.” A rare copy of this map was recently found in Germany(e).

Nevertheless, from the early 1600’s dissenting voices were raised, such as those of José de Acosta, and Michel de Montaigne.

As late as 1700, a map of the world by Edward Wells was published in Oxford that highlights the paucity of information regarding the Americas at that time. However, in this instance the accompanying text notes that “this continent with the adjoining islands is generally supposed to have been anciently unknown though there are not wanting some, who will have even the continent itself to be no other than the Insula Atlantis of the ancients.”

For over five centuries a variety of commentators have associated Atlantis with America and many of its ancient cultures together with a range of location theories that stretch from Maine through the Caribbean and Central America to Argentina.

Although most proponents of an American Atlantis, particularly following the continent’s discovery, did not specify a location but were happy to consider the Americas in their entirety as Plato’s lost land. In 2019, Reinoud de Jonge published a paper declaring that from 2500-1200 BC America had been an Egyptian colony. He expanded on this in 2912(l), when he claimed that the American colonies, North and South had supplied the copper and tin for the Bronze Age of the Mediterranean. For good measure, he threw in a wildly speculative translation of the Phaistos Disk to support these contentions.

Over time attention was more focused on Mesoamerica and the northern region of South America, where the impressive remains of the Maya and Incas led many to consider them to be Atlantean.

North America received minimal attention until the 19th century when an 1873 newspaper report(i) claimed that there was support from unnamed scientists for locating remnants of Atlantis in the Adirondacks and some of the mountains of Maine! More recently Dennis Brooks has advocated Tampa Bay, Florida, while John Saxer supports Tarpon Springs, also in Florida as Atlantean. To confuse matters further, Mary Sutherland locates Atlantis in the Appalachian Mountains of Kentucky and for good measure suggests that King Solomon’s mines are to be found in the same region!

For example, the discovery of the remains of the remarkable cultures of Mesoamerica generated speculation on the possibility of an Atlantean connection there. This view gained further support with the publication of Ignatius Donnelly’s groundbreaking work on Atlantis.

Some have seen an Atlantic location for Atlantis as a conduit between the culture of ancient Egypt and that of Meso-America(d).

Half a century ago Nicolai Zhirov claimed that Plato had knowledge of America [458.22] indicated by his statement that Atlantis was in a sea with a continent encompassing it. He thought that this was the earliest record of a continent beyond the Atlantic.

However, Plato also said that Atlantis was surrounded ‘on all sides’ by this continent, which is not compatible with the Azores, advocated by Zhirov as the location of Plato’s sunken island. In an effort to strengthen this claim Zhirov also claims that there is evidence that King Sargon of Akkad travelled to America in the middle of the third millennium BC, an idea that has gained little traction.

The idea of Sumerians in America was promoted by A.H. Verrill and his wife Ruth, who claimed [838] that King Sargon travelled to Peru, where he was known as Viracocha. The Verrills support their contention with a range of cultural, linguistic and architectural similarities between the Sumerians and the Peruvians.

More recently, Andrew Collins has promoted the idea of Atlantis in the Caribbean, specifically Cuba. Followers of Edgar Cayce are still expecting the Bahamas to yield evidence of Plato’s island. Gene Matlock supports the idea of a Mexican location with an Indian connection, while Duane McCullough opts for Guatemala. Ivar Zapp and George Erikson have also chosen Central America for investigation. Further south Jim Allen has argued strongly for Atlantis having been located on the Altiplano of Bolivia. A website entitled American Atlantis Research from Edward Alexander , now offline, was rather weak on content and irritatingly referred to the ‘Andies’.

Although much of what has been written about an American location for Atlantis is the result of serious research, it all falls far short of convincing me that the Atlantis of which Plato wrote is to be found there. No evidence has been produced to even hint that any American culture had control of the Mediterranean as far Tyrrhenia in the north and Libya in the south. No remains or carvings of triremes or chariots have been found in the Americas. How could an ancient civilisation from America launch an attack across the Atlantic and at the furthest end of the Mediterranean 9,000 or even 900 years before Solon? An even more important question is, why would they bother? There is no evidence of either motive, means or opportunity for an attack from that direction.

A number of Plato’s descriptions of Atlantis would seem to rule out America as its location.

(a) As mentioned above, the ‘opposite continent’ referred to by Plato (Timaeus 25a) is described as encompassing the sea in which Atlantis lay. America cannot be described as enclosing the Atlantic. Around 550 AD, Procopius noted that when viewed from the southern side of the Strait of Gibraltar “the whole continent opposite this was named Europe”(m) (not America)!

(b) The Greeks only knew of three continents, Europe, Asia and Libya. Armin Wolf, the German historian, when writing about Scheria relates(f) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and was quite possibly referring to that same part of Italy which later became known as ‘Magna Graecia’. Robert Fox in The Inner Sea[1168.141] confirms that this long-standing usage of ‘continent’ refers to Italy.

(c) Herodotus described Sardinia as “the biggest island in the world” (Hist.6.2). In fact Sicily is marginally larger but as islands were measured in those days (Felice Vinci) [019] by the length of their coastal perimeter Herodotus was correct. Consequently, it can be argued that since Cuba and Hispaniola are much more extensive than Sardinia, the Greeks had no knowledge of the Caribbean.

(d) Plato makes frequent references to horses in Atlantis. The city itself had a track for horseracing (Critias 117c). The Atlanteans had thousands of chariots (Critias 119a). The Atlanteans even had horse baths (Critias 117b). All these references make no sense if Plato was describing an American Atlantis as there were no horses there for over 12,000 years, when they died out, until brought back by the Spaniards millennia later. Furthermore, it makes even less sense if you subscribe to the early date (9600 BC) for Atlantis as it is thousands of years before we have any evidence for the domestication of the horse, anywhere.

A recent study of worldwide DNA patterns suggests that “no more than 70 people inhabited North America 14,000 years ago.”(b) But a more important claim has been offered by Professors Jennifer Raff and Deborah Bolnick who have co-authored a paper offering evidence(j) that the genetic data only supports a migration from Siberia to America. This certainly runs counter to any suggestion of transatlantic migration from Europe.In 1900,

Peter de Roo put forward the idea that the ancient Greeks had knowledge of America, despite the fact that Herodotus clearly said that only three continents were known to them [Histories 4.42]. A 2013 book, L’America dimenticata [1060], by Italian physicist and philologist Lucio Russo, also claims that the ancient Greeks had knowledge of America and it was gradually forgotten because of mistakes made by Ptolemy including a 15-degree error for the latitude of the Canaries(g).

However, the idea that the Greeks had an awareness of America persists, with some claiming that they had colonies in Canada. Among these are Lucio Russo, Ioannis Liritzis(n) and Minas Tsikritsis(p). Manolis Koutlis has gone one further and claims that not only were there Greek Colonies in Canada but that Atlantis had been situated in the Gulf of St. Lawrence(o).

The late Professor Antonis Kontaratos placed the capital of Atlantis at Poverty Point in Louisiana or it at least inspired some of Plato’s description since “there is also solid evidence that the Greeks were travelling to America in prehistoric times too and could have witnessed firsthand the impressive earthworks at Poverty Point, information which could have reached Plato independently as a fading legend [0750].” Kontaratos cited Plutarch to support his contention of Greek transatlantic travel in prehistory.

I note that there is a suspiciously disproportionate number of Greeks supporting the idea of pre-Columbian Hellenic visitors to America!

While there is extensive debate regarding the Americas being visited by ancient Greeks (Minoans), Phoenicians and even Sumerians, there seems little doubt that America had been visited by various other peoples prior to Columbus such as Welsh, Vikings or Irish. The case for the latter is strengthened by a 500-year-old report(h) of a long-established Irish colony in North America called Duhare.

America as Atlantis and the source of freemasonry knowledge was recently repackaged in a brief article on the Odyssey website(k) quoting Manly P. Hall who in turn cited Plato and Sir Francis Bacon. It then proceeds to speculate on what lessons the story of this original American Atlantis offers the America of today!

(c) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waldseem%C3%BCller_map

(d) https://www.africaspeaks.com/reasoning/index.php?topic=5106.0

(f) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(g) Reconsidering History: Ancient Greeks Discovered America Thousands of Years Ago (archive.org) *

(j) https://phys.org/news/2016-01-genetic-ancient-trans-atlantic-migration-professor.html

(k) https://www.theodysseyonline.com/america-as-atlantis

(l) https://www.academia.edu/3894415/COPPER_AND_TIN_FROM_AMERICA_c.2500-1200_BC_

(m) Vandal Wars 1.1.7

(n) https://www.hakaimagazine.com/news/did-ancient-greeks-sail-to-canada/