Apollonius of Rhodes

Joramo, Morten Alexander

Morten Alexander Joramo is a Norwegian astrologer, musician and author. In his 2011 book, The Homer Code[1075], he is heavily influenced by Felice Vinci, who situated Homer’s Odyssey in the northern European region. Joramo specifically identifies the island of Trenyken, in Norway’s Outer Lofoten Islands, with Homer‘s legendary Thrinacia. He also refers to the work of Iman Wilkens and Jürgen Spanuth. He also introduces the Bock Saga in support of his contention that “that there must have been an advanced culture in the high north thousands of years ago.”(a)

Morten Alexander Joramo is a Norwegian astrologer, musician and author. In his 2011 book, The Homer Code[1075], he is heavily influenced by Felice Vinci, who situated Homer’s Odyssey in the northern European region. Joramo specifically identifies the island of Trenyken, in Norway’s Outer Lofoten Islands, with Homer‘s legendary Thrinacia. He also refers to the work of Iman Wilkens and Jürgen Spanuth. He also introduces the Bock Saga in support of his contention that “that there must have been an advanced culture in the high north thousands of years ago.”(a)

Although the author touches on the subject of Atlantis in The Homer Code he expands more fully on it the following year in Atlantis Unveiled[1076]. In it he again follows much of Vinci’s work as well as Spanuth’s identification of Helgoland as the location of Atlantis. He also uses Homer as well as copious extracts from Apollonius of Rhodes to justify his identification of Northern Europe as the backdrop to both the Odyssey and Plato’s Atlantis narrative.

Up to this point I found his work interesting, if not convincing. However, when I got to his ancient alien conspiracy theory and the use magic mushrooms, I cried halt.

In 2015, Joramo published The Lost Civilization of the North[1170], which is intended to supplant Atlantis Unveiled.

(a) https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/11337705-the-homer-code

(b) https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22156233-atlantis-unveiled

Jason and the Argonauts (L)

Jason and the Argonauts and the quest for the Golden Fleece is recorded by Apollonius of Rhodes in his epic poem Argonautica. Although there are variants of some of the details in versions recounted by other authors, many researchers have felt that there was a kernel of truth in the story. Tim Severin was one of them and was inspired to retrace the voyage of the Argo in a replica of the ship, which led to the publication of The Jason Voyage[959]. Decades later Dr Marcus Vaxevanopoulos of the Geology Department of the University of Thessaloniki in Greece expressed his belief that there is some reality behind the story of Jason and the Argonauts(a).

Although this has no direct bearing on the Atlantis story, when you combine these euhemeristic ideas along with Schliemann’s discovery of Troy after viewing Homer’s Iliad in a similar manner, it is understandable that many have sought the truth underlying Plato’s Atlantis narrative.

(a) https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/jason-and-legendary-golden-fleece-001307

Syrtis

Syrtis was the name given by the Romans to two gulfs off the North African coast; Syrtis Major which is now known as the Gulf of Sidra off Libya and Syrtis Minor, known today as the Gulf of Gabes in Tunisian waters. They are both shallow sandy gulfs that have been feared from ancient times by mariners. In the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 27.13-18) it is described how St. Paul on his way to Rome was blown off course and feared that they would run aground on ‘Syrtis sands.’

However, they were shipwrecked on Malta or as some claim on Mljet in the Adriatic.

The earliest modern reference to these gulfs that I can find in connection with Atlantis was by Nicolas Fréret in the 18th century when he proposed that Atlantis may have been situated in Syrtis Major. Giorgio Grongnet de Vasse expressed a similar view around the same time. Since then there has been little support for the idea until recent times when Winfried Huf designated Syrtis Major as one of his five divisions of the Atlantean Empire.

However, the region around the Gulf of Gabes has been more persistently associated with aspects of the Atlantis story. Inland from Gabes are the chotts, which were at one time connected to the Mediterranean and considered to have been part of the legendary Lake Tritonis, sometimes suggested as the actual location of Atlantis.

In the Gulf itself, Apollonius of Rhodes placed the Pillars of Herakles(a) , while Anton Mifsud has drawn attention[0209] to the writings of the Greek author, Palefatus of Paros, who stated (c. 32) that the Columns of Heracles were located close to the island of Kerkennah at the western end of Syrtis Minor. Lucanus, the Latin poet, located the Strait of Heracles in Syrtis Minor. Mifsud has pointed out that this reference has been omitted from modern translations of Lucanus’ work!

Férréol Butavand was one of the first modern commentators to locate Atlantis in the Gulf of Gabés[0205]. In 1929 Dr. Paul Borchardt, the German geographer, claimed to have located Atlantis between the chotts and the Gulf, while more recently Alberto Arecchi placed Atlantis in the Gulf when sea levels were lower(b) . George Sarantitis places the ‘Pillars’ near Gabes and Atlantis itself inland, further west in Mauritania, south of the Atlas Mountains. Antonio Usai also places the ‘Pillars’ in the Gulf of Gabes.

In 2018, Charles A. Rogers published a paper(c) on the academia.edu website in which he identified Tunisia as Atlantis with it capital located at the mouth of the Triton River on the Gulf of Gabes. He favours Plato’s 9.000 ‘years’ to have been lunar cycles, bringing the destruction of Atlantis into the middle of the second millennium BC and coinciding with the eruption of Thera which created a tsunami that ran across the Mediterranean destroying the city with the run-up and its subsequent backwash. This partly agrees with my conclusions in Joining the Dots!

Also See: Gulf of Gabes and Tunisia

(a) Argonautica Book IV ii 1230

(c) https://www.academia.edu/36855091/Atlantis_Once_Lost_Now_Found?auto=download*

Herrmann, Albert

Albert Herrmann (1886-1945) was Professor of Geography at Berlin University. He was very interested in oriental geography and is perhaps best known for his 1935, Historical and Commercial Atlas of China, which was widely used

His other passion was Atlantis, so between 1927 and 1931 he declared support for Borchardt’s northwest Africa location theory in a number of publications. In 1938 he used is influence to mount a large exhibition in Berlin about Atlantis(a).

He agreed that a large dried-up saltwater lake in Tunisia called Shott el Djerid was originally Lake Tritonis and was known during Solon’s time as the ‘Atlantic Sea’ and further claimed that it had been the location of Atlantis; a theory supported by a number of investigators. In more recent times, Charles A. Rogers is one such advocate of this identification(b).

Herrmann suggested that it was the result of an upheaval of the land, which extended a land barrier between the Shott and the sea. He locates the Pillars of Heracles where this barrier was created. Anton Mifsud has pointed out that the 1st century BC writer Apollonius Rhodius located the Strait of Heracles in ancient Syrtis Minor, now the Gulf of Gabés, apparently supporting Herrmann’s contention. At one point, Herrmann cited as Atlantis, the village of Rhelissa, near the mouth of the old River Tritonis, which flowed into the Gulf of Gabes.

Herrmann disagreed with Plato’s 9,000 years and proposed that he had instead been referring to the 13th or 14th century BC.

Finally, Herrmann, in an effort to match this location with the Platonic narrative, felt obliged to reduce its dimensions by a factor of thirty. He claimed that the priest or interpreter at Sais had erred in the conversion of the Egyptian ‘schoinos’ into Greek stadia. The schoinos was adopted by the Greeks, where it must be noted that it, as well as the Geek stadion, had variable regional values; the number of schoeni per stadion varied between 30 and 120.

In a later book[386], Herrmann shifted his view from his original stance suggesting that Tunisia had been just a colony under the influence of a culture originating in Friesland, later to become famous as the source of the Oera Linda Book (c). It is not impossible that the introduction of a Northern European slant to his theories was the consequence of political pressure in Germany at the time, typified by Borchardt being imprisoned because of his Jewish background. Vidal-Naquet describes Herrmann as ‘an avowed Nazi’ [580.121] so pressure may not have been necessary. (a) >His revised conclusions appear to mirror the views of fellow nazi Hermann Wirth.<

(b) https://www.academia.edu/36855091/Atlantis_Once_Lost_Now_Found

Eridanus

Eridanus is the name of a constellation in the Southern Hemisphere as well as the name of the only Atlantean river named by Plato (Crit. 112a). It has been identified with a number of waterways(b) including the Nile (Eratosthenes), the Eider (Spedicato)(d), the Rhine(f), the Istros (Danube) of Hungary(g) and the Po (H. S. Bellamy). Mythology has fiery Phaëton crashing into the Eridanus, which means ‘early burnt’.

Adding to the confusion is the existence of the River Eridanos, referred to by Plato (Phaedrus 229) which is a tributary of the Ilissos and is still partly visible in the centre of modern Athens(e). (see left image)

Adding to the confusion is the existence of the River Eridanos, referred to by Plato (Phaedrus 229) which is a tributary of the Ilissos and is still partly visible in the centre of modern Athens(e). (see left image)

Jürgen Spanuth was convinced that it was as either the Elder or the Eider, which flow into the North Sea opposite Helgoland. Emilio Spedicato echoed Spanuth’s views in a number of more recent articles(c)(d) and opted for the Eider as the original Eridanus. The similarity of the two names also adds some credence to this idea.

The late Walter Baucum quoted[183.159] the Swiss historian and geographer, Frederic de Rougemont (1808-1876), who, in his 1866 book, L’Age de Bronze, ‘proved’ that originally the Rhine had been known as the Eridanus.

Apollonius of Rhodes in his Argonautica refers to the River Eridanus as flowing into the Cronian Sea(a), generally accepted as the North Atlantic. The Eridanus is frequently referred to in ancient Greek texts as an amber-rich river in Northern Europe. Amber was claimed by Spanuth to have been the Orichalcum of Plato’s Atlantis.

Kai Helge Wirth[627], a German geographer, has advanced the controversial theory that the configuration of the constellations was chosen to conform with the outlines of various Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts and was used as navigational aids to ancient mariners. As part of this radical idea, Wirth has pointed out that the constellation Eridanus closely follows the meandering Eider rather than the Po.

Geologists have given the name Eridanus to a river which flowed where the Baltic is now located. Claudius Ptolemy identified the River Duna, which flows into the Gulf of Riga in the Baltic, as the Eridanus.

(a) http://www.theoi.com/Text/ApolloniusRhodius4.html

(b) Star Tales – Eridanus (ianridpath.com)

(c) https://www.2008-paris-conference.org/mapage13/phaethon-to-chapamacac.pdf

(d) Wayback Machine (archive.org) *

(e) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eridanos_(Athens)

(f) https://www.bibletools.org/index.cfm/fuseaction/Topical.show/RTD/CGG/ID/2236/Danube.htm

(g) https://www.theoi.com/Potamos/PotamosEridanos.html

Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius of Rhodes (Apollonius Rhodius) (c.270 BC) was the chief librarian at Alexandria during the 3nd century BC. His  best-known work is the Argonautica [0668], a reworking of the voyage of the Argonauts, in whicht he refers to the island of Atlantides. Anton Mifsud has pointed out that in early editions of this book, Apollonius located the Straits of Heracles in Syrtis Minor (Bk.IV ii.1230) as well as the existence of shoals in that gulf. However, Mifsud notes that modern translations omit this reference. Syrtis Minor was the Roman name for the Gulf of Gabés. Lucanus, who is more usually known as Lucan by English readers, echoed this same identification.

best-known work is the Argonautica [0668], a reworking of the voyage of the Argonauts, in whicht he refers to the island of Atlantides. Anton Mifsud has pointed out that in early editions of this book, Apollonius located the Straits of Heracles in Syrtis Minor (Bk.IV ii.1230) as well as the existence of shoals in that gulf. However, Mifsud notes that modern translations omit this reference. Syrtis Minor was the Roman name for the Gulf of Gabés. Lucanus, who is more usually known as Lucan by English readers, echoed this same identification.

Shoals of Mud

A Shoal of mud is stated by Plato (Tim.25d) to mark the location of where Atlantis ‘settled’. He described these shallows in the present tense, clearly implying that they were still a maritime hindrance even in Plato’s day.

Three of the most popular translations clearly indicate this:

….the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.

…..the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal of mud which the island created as it settled down.”

…..the sea in that area is to this day impassible to navigation, which is hindered by mud just below the surface, the remains of the sunken island.

Wikipedia has noted(h) that “during the early first century, the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo wrote about the destruction of Atlantis in his On the Eternity of the World, xxvi. 141, in a longer passage allegedly citing Aristotle’s successor Theophrastus.

‘ And the island of Atalantes [translator’s spelling; original: “????????”] which was greater than Africa and Asia, as Plato says in the Timaeus, in one day and night was overwhelmed beneath the sea in consequence of an extraordinary earthquake and inundation and suddenly disappeared, becoming sea, not indeed navigable, but full of gulfs and eddies’.”

Since it is probable that Atlantis was destroyed around a thousand years or more before Solon’s Egyptian sojourn, to have continued as a hazard for such a period suggests a location that was little affected by currents or tides. The latter would seem to offer support for a Mediterranean Atlantis as that sea enjoys negligible tidal changes, as can be seen from the chart below. The darkest shade of blue indicates the areas of minimal tidal effect.

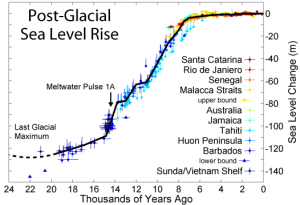

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

The reference to mud shoals resulting from an earthquake brings to mind the possibility of liquefaction. This is perhaps what happened to the two submerged ancient cities close to modern Alexandria. Their remains lie nine metres under the surface of the Mediterranean.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Some supporters of a Black Sea Atlantis have suggested the shallow Strait of Kerch between Crimea and Russia as the location of Plato’s ‘shoals’(e) .

The tidal map above offers two areas west of Athens and Egypt that do appear to be credible location regions, namely, (1) from the Balearic Islands, south to North Africa and (2), a more credible straddling the Strait of Sicily. This region offers additional features, making it much more compatible with Plato’s account.

By contrast, just over a hundred miles south of that Strait, lies the Gulf of Gabés, which boasts the greatest tidal range (max 8 ft) within the Mediterranean.

The Gulf of Gabes formerly known as Syrtis Minor and the larger Gulf of Sidra to the east, previously known as Syrtis Major, was greatly feared by ancient mariners and continue to be very dangerous today because of the shifting sandbanks created by tides in the area.

There are two principal ancient texts that possibly support the gulfs of Syrtis as the location of Plato’s ‘shoal’. The first is from Apollonius of Rhodes who was a 3rd-century BC librarian at Alexandria. In his Argonautica (Bk IV ii 1228-1250)(a) he unequivocally speaks of the dangerous shoals in the Gulf of Syrtis. The second source is the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 27 13-18) written three centuries later, which describes how St. Paul on his way to Rome was blown off course and feared that they would run aground on “Syrtis sands.” However, good fortune was with them and after fourteen days they landed on Malta. The Maltese claim regarding St. Paul is rivalled by that of the Croatian island of Mljet as well Argostoli on the Greek island of Cephalonia. Even more radical is the convincing evidence offered by Kenneth Humphreys to demonstrate that the Pauline story is an invention(b).

Both the Strait of Sicily and the Gulf of Gabes have been included in a number of Atlantis theories. The Strait and the Gulf were seen as part of a larger landmass that included Sicily according to Butavand, Arecchi and Sarantitis who named the Gulf of Gabes as the location of the Pillars of Heracles. Many commentators such as Frau, Rapisarda and Lilliu have designated the Strait of Sicily as the ‘Pillars’, while in the centre of the Strait we have Malta with its own Atlantis claims.

Zhirov[458.25] tried to explain away the ‘shoals’ as just pumice stone, frequently found in large quantities after volcanic eruptions. However, Plato records an earthquake, not an eruption and Zhirov did not explain how the pumice stone was still a hazard many hundreds of years after the event. Although pumice can float for years, it will eventually sink(c). It was reported that pumice rafts associated with the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa were found floating up to 20 years after that event. Zhirov’s theory does not hold water (no pun intended) apart from which, Atlantis was destroyed as a result of an earthquake. not a volcanic eruption and I think that the shoals described by Plato were more likely to have been created by liquefaction and could not have endured for centuries.

Nevertheless, a lengthy 2020 paper(d) by Ulrich Johann offers additional information about pumice and in a surprising conclusion proposes that it was pumice rafts that inspired Plato’s reference to shoals!

Andrew Collins in an effort to justify his Cuban location for Atlantis needed to find Plato’s ‘shoals of mud’ in the Atlantic and for me, in what seems to have been an act of desperation he decided that the Sargasso Sea fitted the bill [072.42]. Similarly, Emilio Spedicato in support of a Hispaniola Atlantis also opted for the Sargasso. However, neither Collins or Spedicato were the first to make this suggestion. Chedomille Mijatovich (1842-1932), a Serbian politician, economist and historian was one of the first in modern times to suggest that the Sargasso Sea may have been the maritime hazard described by Plato as a ‘shoal of mud’, which resulted from the submergence of Atlantis. However, neither explains how anyone can mistake seaweed for mud!

The late Andis Kaulins believed that Atlantis did exist and considered two possible regions for its location; the Minoan island of Thera or some part of the North Sea that was submerged at the end of the last Ice Age when the sea levels rose dramatically. Kaulins noted that part of the North Sea is known locally as ‘Wattenmeer’ or Sea of Mud’ reminiscent of Plato’s description of the region where Atlantis was submerged, after that event.

An even more absurd suggestion came from the American scholar William Arthur Heidel (1868-1941), who denied the reality of Atlantis and wrote a critical paper [0374] on the subject (republished July 2013(g)). He claimed that an expeditionary naval force sent by Darius in 515 BC under Scylax of Caryanda to explore the Indus River, eventually encountered waters too shallow for his ships, and that this was the inspiration behind Plato’s tale of unnavigable seas. Heidel further claimed that Plato’s battle between Atlantis and Athens is a distorted account of the war of invasion between the Persians and the peoples of the Indus Valley (Now Pakistan)!

(a) https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/argo/argo53.htm

(b) The Curious Yarn of Paul’s “Shipwreck” (archive.org) *

(c) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170523144110.htm

(e) Index (atlantis-today.com)

(f) https://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread61382/pg1

(g) A Suggestion concerning Plato’s Atlantis on JSTOR (archive.org)

(h) Atlantis – Wikipedia_?s=books&ie=UTF&qid=1376067567&sr=-