Seville

Huelva

Huelva is a city in southwest Spain that has frequently featured in the search for Tartessos. Adolph Schulten(a) as well as Jorge Bonsor devoted years to studying Huelva, Cádiz and Seville in their search for the legendary city. Even if Tartessos is conclusively identified, it is still a long way from proving it to be Plato’s Atlantis, which after all is supposed to be submerged. I was recently offered satellite images that purported to show traces of ground features that ‘might’ indicate ancient ruins with a remote possibility that they might be part of Tartessos!

(a) https://www.uv.es/~alabau/situacion.htm (Sp) (link broken Mar 2019 See: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217151230/https://www.uv.es/~alabau/situacion.htm

Tartessos

Tartessos or Tartessus is generally accepted to have existed along the valley of the Guadalquivir River where the rich deposits of copper and silver led to the development of a powerful native civilisation, which traded with the Phoenicians, who had colonies along the south coast of Spain(k).

A continuing debate is whether Tartessos was developed by a pre-Phoenician indigenous society or was a joint venture by locals along with the Phoenicians.(o) One of the few modern English-language books about Tartessos was written by Sebastian Celestino & Carolina López-Ruiz and entitled Tartessos and the Phoenicians in Iberia [1900].

A 2022 BBC article offers some additional up-to-date developments in the studies of Tartessos(v).

It is assumed by most commentators that Tartessos was identical to the wealthy city of Tarshish that is mentioned in the Bible. There have been persistent attempts over the past century to link Tartessos with Atlantis. The last king of Tartessia, in what is now Southern Spain, is noted by Herodotus to have been Arganthonios, who is claimed to have ruled from 630 BC until 550 BC. Similarly, Ephorus a 4th century BC historian describes Tartessos as ‘a very prosperous market.’ However, if these dates are only approximately true, then Atlantis cannot be identified with Tartessos as they nearly coincide with the lifetime of Solon, who received the story of Atlantis as being very ancient.

However, the suggested linkage of Tartessos with Atlantis is disputed by some Spanish researchers, such as Mario Mas Fenollar [1802] and Ester Rodríguez González(n). Mas Fennolar has claimed that at least a thousand years separated the two. Arysio dos Santos frequently claimed that Atlantis was Tartessos throughout his Atlantis and the Pillars of Hercules [1378].

The existence of a ‘Tartessian’ empire is receiving gradual acceptance. Strabo writes of their system of canals running from the Guadalquivir River and a culture that had written records dating back 6,000 years. Their alphabet was slightly different to the ‘Iberian’. The Carthaginians were said to have been captured by Tartessos after the reign of Arganthonios and after that, contact with Tartessos seems to have ended abruptly!

The exact location of this city is not known apart from being near the mouth of the Guadalquivir River in Andalusia. The Guadalquivir was known as Baetis by the Romans and Tartessos to the Greeks. The present-day Gulf of Cadiz was known as Tartessius Sinus (Gulf of Tartessus) in Roman times. Cadiz is accepted to be a corruption of Gades that in turn is believed to have been named after Gaderius. This idea was proposed as early as 1634 by Rodrigo Caro (image left), the Spanish historian and poet, in his Antigüedades y principado de la Ilustrísima ciudad de Sevilla, now available as a free ebook(i).

In 1849, the German researcher Gustav Moritz Redslob (1804-1882) carried out a study of everything available relating to Tartessos and concluded that the lost city had been the town of Tortosa on the River Ebro situated near Tarragona in Catalonia. The idea seems to have received little support until recently, when Carles Camp published a paper supporting this contention(w). It was written in Valenciano, which is related to Catalan and can be translated with Google Translate using the latter option.

A few years ago, Richard Cassaro endeavoured to link the megalithic walls of old Tarragona with the mythical one-eyed Cyclops and for good measure suggest a link with Atlantis(l). Concerning the giants, the images of doorways posted by Cassaro are too low to comfortably accommodate giants! Cassaro has previously made the same claim about megalithic structures in Italy(m)

The German archaeologist Adolf Schulten spent many years searching unsuccessfully for Tartessos, in the region of the Guadalquivir. He believed that Tartessos had been founded by Lydians in 1150 BC, which became the centre of an ancient culture that was Atlantis or at least one of its colonies. Schulten also noted that Tartessos disappeared from historical records around 500 BC, which is after Solon’s visit to Egypt and so could not have been Atlantis.

Richard Hennig in the 1920s also supported the idea of Tartessos being Atlantis and situated in southern Spain. However, according to Atlantisforschung he later changed his opinion opting to adopt Spanuth’s Helgoland location instead(x).

Otto Jessen, a German geographer, also believed that there had been a connection between Atlantis and Tartessos. Jean Gattefosse was convinced that the Pillars of Heracles were at Tartessos, which he identifies as modern Seville. However, Mrs E. M. Whishaw, who studied in the area for 25 years at the beginning of the 20th century, believed that Tartessos was just a colony of Atlantis. The discovery of a ‘sun temple’ 8 meters under the streets of Seville led Mrs Whishaw to surmise[053] that Tartessos may be buried under that city. Edwin Björkman wrote a short book, The Search for Atlantis[181] in which he identified Atlantis with Tartessos and also Homer’s Scheria.

book, The Search for Atlantis[181] in which he identified Atlantis with Tartessos and also Homer’s Scheria.

Steven A. Arts, the author of Mystery Airships in the Sky, also penned an article for Atlantis Rising in which he suggests that the Tarshish of the Old Testament is a reference to Tartessos and by extension to Atlantis(r)!

More recently Karl Jürgen Hepke has written at length, on his website(a), about Tartessos. Dr Rainer W. Kühne, following the work of another German, Werner Wickboldt, had an article[429] published in Antiquity that highlighted satellite images of the Guadalquivir valley that he has identified as a possible location for Atlantis. Kühne published an article(b) outlining his reasons for identifying Tartessos as the model for Plato’s Atlantis.

Although there is a consensus that Tartessos was located in Iberia, there have been some refinements of the idea. One of these is the opinion of Peter Daughtrey, expressed in his book, Atlantis and the Silver City[0893] in which he proposes that Tartessos was a state which extended from Gibraltar around the coast to include what is today Cadiz and on into Portugal’s Algarve having Silves as its ancient capital.

It was reported(c) in January 2010 that researchers were investigating the site in the Doñana National Park, at the mouth of the Guadalquivir, identified by Dr Rainer Kühne as Atlantis in a 2011 paper(s). In the same year, Professor Richard Freund of the University of Hartford garnered a lot of publicity when he visited the site and expressed the view that it was the location of Tartessos which he equates with Atlantis. The Jerusalem Post in seeking to give more balance to the discussion quoted archaeology professor Aren Maeir who commented that “Richard Freund is known as someone who makes ‘sensational’ finds. I would say that I am exceptionally skeptical about the thing, but I wouldn’t discount it 100% until I see the details, which haven’t been published as far as I know.”(u)

A minority view is that Tarshish is related to Tarxien (Tarshin) in Malta, which, however, is located some miles inland with no connection to the sea. Another unusual theory is offered by Luana Monte, who has opted for Thera as Tartessos. She bases this view on a rather convoluted etymology(e) which morphed its original name of Therasia into Therasios, which in Semitic languages having no vowels would read as ‘t.r.s.s’ and can be equated with Tarshish in the Bible, which in turn is generally accepted to refer to Tartessos.

Giorgio Valdés favours a Sardinian location for Tartessos(f), an idea endorsed later by Giuseppe Mura in his 2018 book, published in Italian, Tartesso in Sardegna [2068], the full title of which translates as Tartessos in Sardinia: Reasons, circumstances and methods used by ancient historians and geographers to remove Tartessos (the Tarshish of the Bible) from Caralis and place it in Spanish Andalusia. Caralis is an old name for Cagliari, the Sardinian capital.

Andis Kaulins has claimed that further south, in the same region, Carthage was possibly built on the remains of Tartessos, near the Pillars of Heracles(j).

A more radical idea was put forward in 2012 by the Spanish researcher, José Angel Hernández, who proposed(g)(h) that the Tarshish of the Bible was to be found in the coastal region of the Indus Valley, but that Tartessos was a colony of the Indus city of Lhotal and had been situated on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar!

A recent novel by C.E. Albertson[130] uses the idea of an Atlantean Tartessos as a backdrop to the plot.

A relatively recent claim associating Tartessos with Atlantis came from Simcha Jacobovici in a promotional interview(p) for the 2017 National Geographic documentary, Atlantis Rising. In it, Jacobovici was joined by James Cameron as producer, but unfortunately, the documentary did not produce anything of any real substance despite a lot of pre-broadcast hype.

There is an extensive website(d) dealing with all aspects of Tartessos, including the full text of Schulten’s book on the city. Although this site is in Spanish, it is worthwhile using your Google translator to read an English version.

“Today, researchers consider Tartessos to be the Western Mediterranean’s first historical civilization. Now, at an excavation in Extremadura—a region of Spain that borders Portugal, just north of Seville—a new understanding of how that civilization may have ended is emerging from the orange and yellow soil. But the site, Casas del Turuñuelo, is also uncovering new questions.”(q) First surveyed in 2014 it was in late 2021, a report emerged of exciting excavations there that may have a bearing on the demise of Tartessos. Work is currently on hold because of a dispute with landowners, with only a quarter of the site uncovered. The project director is Sebastian Celestino Perez. The Atlas Obscura website offers further background and details of discoveries at the site(t).

(a) http://web.archive.org/web/20170716221143/http://www.tolos.de/History%20E.htm

(b) Meine Homepage (archive.org)

(d) TARTESSOS.INFO: LA IBERIA BEREBER (archive.org)

(e) http://xmx.forumcommunity.net/?t=948627&st=105

(f) http://gianfrancopintore.blogspot.ie/2010/09/atlantide-e-tartesso-tra-mito-e-realta.html

(g) http://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/mito-y-religion/

(h) http://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/arqueologia-e-historia/

(j) Pillars of Heracles – Alternative Location (archive.org)

(k) Archive 3283 | (atlantipedia.ie)

(n) (PDF) Tarteso vs la Atlántida: un debate que trasciende al mito (researchgate.net)

(o) (PDF) Definiendo Tarteso: indígenas y fenicios (researchgate.net)

(p) Lost City of Atlantis And Its Incredible Connection to Jewish Temple (israel365news.com)

(q) The Ancient People Who Burned Their Culture to the Ground – Atlas Obscura

(r) Atlantis Rising magazine #36 http://pdfarchive.info/index.php?pages/At

(t) https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/tartessos-casas-del-turunuelo

(u) https://www.jpost.com/jewish-world/jewish-news/the-deepest-jewish-encampment

(v) https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20220727-the-iberian-civilisation-that-vanished

(w) https://www.inh.cat/articles/La-localitzacio-de-Tartessos-es-desconeguda.-Pot-ser-Tartessos-Tortosa- *

(x) Richard Hennig – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog) *

Concentric Rings *

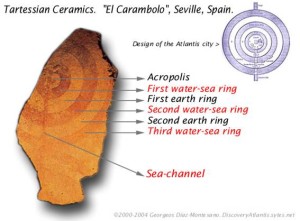

The Concentric Rings or other architectural features extracted by artists from Plato’s description of the capital of Atlantis have  continually fascinated students of the story and many have attempted to link them with similar ancient features found elsewhere in the world as evidence of a widespread culture. Stonehenge, Old Owstrey, Carthage and Syracuse have all been suggested, but such comparisons have never been convincing. Diaz-Montexano has recently published(a) an image of a fragment of pottery found near Seville in Spain that shows concentric circles and insists that it is a symbol of Atlantis. Ulf Erlingsson has made a similar claim regarding some concentric circles carved on a stone basin found at Newgrange in Ireland.

continually fascinated students of the story and many have attempted to link them with similar ancient features found elsewhere in the world as evidence of a widespread culture. Stonehenge, Old Owstrey, Carthage and Syracuse have all been suggested, but such comparisons have never been convincing. Diaz-Montexano has recently published(a) an image of a fragment of pottery found near Seville in Spain that shows concentric circles and insists that it is a symbol of Atlantis. Ulf Erlingsson has made a similar claim regarding some concentric circles carved on a stone basin found at Newgrange in Ireland.

Less well-known are the concentric stone circles that are to be found on the island of Lampedusa in the Strait of Sicily(b).

In 1969 two commercial pilots, Robert Brush and Trigg Adams photographed a series of large concentric circles in about three feet of water off the coast of Andros in the Bahamas. Estimates of the diameter of the circles range from 100 to 1,000 feet. Apparently, these rings are now covered by sand. It is hard to understand how such a feature in such very shallow water cannot be physically located and inspected. Richard Wingate in his book [0059] estimated the diameter at 1,000 yards. However, the rings described by Wingate were apparently on land, among Andros’ many swamps.

A recent (2023) report has drawn attention to the ancient rock art found on Kenya’s Mfangano Island where a number of concentric circles estimated as 4,000 years old can be seen(q).

Two papers presented to the 2005 Atlantis Conference on Melos describe how an asteroid impact could produce similar concentric rings, which, if located close to a coast, could be converted easily to a series of canals for seagoing vessels. The authors, Filippos Tsikalas, V.V. Shuvavlov and Stavros Papamarinopoulos gave examples of such multi-ringed concentric morphology resulting from asteroid impacts. Not only does their suggestion provide a rational explanation for the shape of the canals but would also explain the apparent over-engineering of those waterways.

At the same conference, the late Ulf Richter presented his idea [629.451], which included the suggestion that the concentric rings around the centre of the Atlantis capital had a natural origin. Richter has proposed that the Atlantis rings were the result of the erosion of an elevated salt dome that had exposed alternating rings of hard and soft rock that could be adapted to provide the waterways described by Plato.

Georgeos Diaz-Montexano has suggested that the ancient city under modern Jaen in Andalusia, Spain had a concentric layout similar to Plato’s description of Atlantis. In August 2016 archaeologists from the University of Tübingen revealed the discovery(i) of a Copper Age, Bell Beaker People site 50km east of Valencina near Seville, where the complex included a series of concentric earthwork circles.

A very impressive example of man-made concentric stone circles, known in Arabic as Rujm el-Hiri and in Hebrew as Gilgal Refaim(a), is to be found on the Golan Heights, now part of Israeli-occupied Syria. It consists of four concentric walls with an outer diameter of 160metres. It has been dated to 3000-2700 BC and is reputed to have been built by giants! Mercifully, nobody has claimed any connection with Atlantis. That is until 2018 when Ryan Pitterson made just such a claim in his book, Judgement of the Nephilim[1620].

Jim Allen in his latest book, Atlantis and the Persian Empire[877], devotes a well-illustrated chapter to a discussion of a number of ‘circular cities’ that existed in ancient Persia and which some commentators claim were the inspiration for Plato’s description of the city of Atlantis. These include the old city of Firuzabad which was divided into 20 sectors by radial spokes as well as Ecbatana and Susa, both noted by Herodotus to have had concentric walls. Understandably, Allen, who promotes the idea of Atlantis in the Andes, has pointed out that many sites on the Altiplano have hilltops surrounded by concentric walls. However, as he seems to realise that to definitively link any of these locations with Plato’s Atlantis a large dollop of speculation was required.

Rodney Castleden compared the layout of Syracuse in Sicily with Plato’s Atlantis noting that the main city “had seen a revolution in its defensive works, with the building of unparalleled lengths of circuit walls punctuated by numerous bastions and towers, displaying the city-state’s power and wealth. The three major districts of the city, Ortygia, Achradina and Tycha, were surrounded by three separate circuit walls; Ortygia itself had three concentric walls, a double wall around the edge and an inner citadel”.[225.179]

Dale Drinnon has an interesting article(d) on the ‘rondels’ of the central Danubian region, which number about 200. Some of these Neolithic features have a lot in common with Plato’s description of the port city of Atlantis. The ubiquity of circular archaeological structures at that time is now quite clear, but they do not demonstrate any relationship with Atlantis.

The late Marcello Cosci based his Atlantis location on his interpretation of aerial images of circular features on Sherbro Island, but as far as I can ascertain this idea has gained little traction.

One of the most remarkable natural examples of concentric features is to be found in modern Mauritania and is known as the Richat Structure or Guelb er Richat. It is such a striking example that it is not surprising that some researchers have tried to link it with Atlantis. Robert deMelo and Jose D.C. Hernandez(o) are two advocates along with George S. Alexander & Natalis Rosen who were struck by the similarity of the Richat feature with Plato’s description and decided to investigate on the ground. Instability in the region prevented this until late 2008 when they visited the site, gathering material for a movie. The film was then finalised and published on their then newly established website in 2010(l), where the one hour video in support of their thesis can be freely downloaded(m).

In 2008, George Sarantitis put forward the idea that the Richat Structure was the location of Atlantis, supporting his contention with an intensive reappraisal of the translation of Plato’s text(n). He developed this further in his Greek language 2010 book, The Apocalypse of a Myth[1470] with an English translation currently in preparation.

However, Ulf Richter has pointed out that Richat is too wide (35 km), too elevated (400metres) and too far from the sea (500 km) to be seriously considered as the location of Atlantis.

A dissertation by Oliver D.Smith has suggested(e) the ancient site of Sesklo in Greece as the location of Atlantis, citing its circularity as an important reason for the identification. However, there are no concentric walls, the site is too small and most importantly, it’s not submerged. Smith later decided that the Atlantis story was a fabrication!(p)

Brad Yoon has claimed that concentric circles are proof of the existence of Atlantis, an idea totally rejected by Jason Colavito(j).

In March 2015, the UK’s MailOnline published a generously illustrated article(g) concerning a number of sites with unexplained concentric circles in China’s Gobi Desert. The article also notes some  superficial similarities with Stonehenge. I will not be surprised if a member of the lunatic fringe concocts an Atlantis theory based on these images. (see right)

superficial similarities with Stonehenge. I will not be surprised if a member of the lunatic fringe concocts an Atlantis theory based on these images. (see right)

Paolo Marini has written Atlantide:Nel cerchio di Stonehenge la chiave dell’enigma (Atlantis: The Circle is the Key to the enigma of Stonehenge) [0713]. The subtitle refers to his contention that the concentric circles of Atlantis are reflected in the layout of Stonehenge!

In 2011 Shoji Yoshinori offered the suggestion that Stonehenge was a 1/24th scale model of Atlantis(f). He includes a fascinating image in the pdf.

This obsession with concentricity has now extended to the interpretation of ancient Scandinavian armoury in particular items such as the Herzsprung Shield(c).

For my part, I wish to question Plato’s description of the layout of Atlantis’ capital city with its vast and perfectly engineered concentric alternating bands of land and sea. This is highly improbable as the layout of cities is invariably determined by the natural topography of the land available to it(h). Plato is describing a city designed by and for a god and his wife and as such his audience would expect it to be perfect and Plato did not let them down. I am therefore suggesting that those passages have been concocted within the parameters of ‘artistic licence’ and should be treated as part of the mythological strand in the narrative, in the same way, that we view the ‘reality’ of Clieto’s five sets of male twins or even the physical existence of Poseidon himself.

Furthermore, Plato was a follower of Pythagoras, who taught that nothing exists without a centre, around which it revolves(k). A concept which may have inspired him to include it in his description of Poseidon’s Atlantis.

(b) Megalithic Lampedusa (archive.org)

(c) https://www.parzifal-ev.de/index.php?id=20

(d) See: Archive 3595

(e) https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-3062/

(f) https://www.pipi.jp/~exa/kodai/kaimei/stonehenge_is_small_atrantis_eng.pdf

(i) First Bell Beaker earthwork enclosure found in Spain | ScienceDaily (archive.org) *

(j) https://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/rings-of-power-do-concentric-circles-prove-atlantis-real

(k) Pythagoras and the Mystery of Numbers (archive.org)

(l) Visiting Atlantis | Gateway to a lost world (archive.org)

(m) https://web.archive.org/web/20171022134926/https://visitingatlantis.com/Movie.html

(n) https://platoproject.gr/system-wheels/ https://platoproject.gr/page13.html (offline Nov.2015)

(o) https://blog.world-mysteries.com/science/a-celestial-impact-and-atlantis/ (item 11)

(p) https://shimajournal.org/issues/v10n2/d.-Smith-Shima-v10n2.pdf

Andalusia *

Andalusia is the second largest of the seventeen autonomous communities of Spain. It is situated in the south of the country with Seville as its capital, which was earlier known as Spal when occupied by the Phoenicians.

However, there is now evidence that near the town of Orce the remains of the earliest hominids to reach Europe have been discovered. These remains have now been dated to 1.6 million years ago according to a November 2023 article on the BBC website(g).

Andalusia is thought to take its name from the Arabic al-andalus – the land of the  Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Andalusia has been identified by a number of investigators as the home of Atlantis. It appears that the earliest proponents of this idea were José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar and Johannes van Gorp in the 17th century. This view was echoed in the 19th century by the historian Francisco Fernández y Gonzáles and subsequently by his son Juan Fernandez Amador de los Rios in 1919. A decade later Mrs E. M. Whishaw published [053] the results of her extensive investigations in the region, particularly in and around Seville. In 1984, Katherine Folliot endorsed this Andalusian location for Atlantis in her book, Atlantis Revisited [054].

Stavros Papamarinopoulos has added his authoritative voice to the claim for an Andalusian Atlantis in a series of six papers(a) presented to a 2010 International Geological Congress in Patras, Greece. He argues that the Andalusian Plain matches the Plain of Atlantis but Plato clearly describes a plain that was 3,000 stadia long and 2,000 stadia wide and even if the unit of measurement was different, the ratio of length to breadth does not match the Andalusian Plain. Furthermore, Plato describes the mountains to the north of the Plain of Atlantis as being “more numerous, higher and more beautiful” than all others. The Sierra Morena to the north of Andalusia does not fit this description. The Sierra Nevada to the south is rather more impressive, but in that region, the most magnificent is the Atlas Mountains of North Africa. As well as that Plato clearly states (Critias 118b) that the Plain of Atlantis faced south while the Andalusian Plain faces west!

During the same period, the German, Adolf Schulten who also spent many years excavating in the area, was also convinced that evidence for Atlantis was to be found in Andalusia. He identified Atlantis with the legendary Tartessos[055].

Dr Rainer W. Kuhne supports the idea that the invasion of the ‘Sea Peoples’ was linked to the war with Atlantis(f), recorded by the Egyptians and he locates Atlantis in Andalusian southern Spain, placing its capital in the valley of the Guadalquivir, south of Seville. In 2003, Werner Wickboldt, a German teacher, declared that he had examined satellite photos of this region and detected structures that very closely resemble those described by Plato in Atlantis. In June 2004, AntiquityVol. 78 No. 300 published an article(b) by Dr Kuhne highlighting Wickboldt’s interpretation of the satellite photos of the area. This article was widely quoted throughout the world’s press. Their chosen site, the Doñana Marshes were linked with Atlantis over 400 years ago by José Pellicer. Kühne also offers additional information on the background to the excavation(e).

However, excavations on the ground revealed that the features identified by Wickboldt were smaller than anticipated and were from the Muslim Period. Local archaeologists have been working on the site for years until renowned self-publicist Richard Freund arrived on the scene, and spent less than a week there, but subsequently ‘allowed’ the media to describe him as leading the excavations.

Although most attention has been focused on the western end of the region, a 2015 theory(d) from Sandra Fernandez places Atlantis in the eastern province of Almeria.

Georgeos Diaz-Montexano has pointed out that Arab commentators referred to Andalus (Andalusia) north of Morocco as being home to a city covered with golden brass.

Quite a number of modern Spanish authors have opted for Andalusia as the home of Atlantis, such as G.C. Aethelman.

Karl Jürgen Hepke has an interesting website(c) where he voices his support for the idea of two Atlantises (see Lewis Spence) one in the Atlantic and the other in Andalusia.

(a) https://www.researchgate.net/search?q=ATLANTIS%20IN%20SPAIN%20I

(b) See Archive 3135

(c) http://web.archive.org/web/20191227133950/http://www.tolos.de/santorin.e.html

(d) https://atlantesdehoy.wordpress.com/2015/08/06/hola-mundo/

(e) The Archaeological Search for Tartessos-Tarshish-Atlantis – Mysteria3000 (archive.org)

(f) Lehrstuhl für theoretische Physik II (archive.org) *

(g) https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20231114-orce-spain-the-site-of-europes-earliest-settlers

Wickboldt, Werner *

Werner Wickboldt (1943- ) is a teacher and amateur archaeologist, living in Braunschweig, Germany. On January 8, 2003, he gave a lecture on the results of his examination of satellite photos of a region south of Seville, in Parque National Coto de Doñana, he detected structures that very closely resemble those, which Plato described on Atlantis. These structures include a rectangle of size 180 x 90 metres (Temple of Poseidon?) and a square of 180 x 180 meters (Temple of Poseidon and Kleito?). Concentric circles, whose sizes are very close to Plato’s description, surround these two rectangular structures. The largest of these has a radius of 2.5 km. Among the suggested explanations for the structures are; a Roman ‘Castro’, a Viking fort or even a dam for salt production, which is an activity still carried out today in the locality.

In his lecture, Wickboldt went further and claimed that the Atlanteans should be identified as the Sea Peoples(a).

Wickboldt’s discovery inspired Rainer Kühne to develop his theory on Atlantis, which was published in Antiquity. Wickboldt and Kühne hold differing views on various aspects of the Atlantis, which were aired in the comments section of an online forum in 2011(b).

Some debate has developed regarding the actual state of this area in Phoenician times.

It would appear that, during the Roman period, sedimentation brought the mouth of the Guadalquivir about 40 km further south to a position near modern Lebrija. However, in the age of the Tartessians, it was only 13 km south of Seville. If correct this would imply that Wickboldt’s structures were underwater at the time of Plato’s Atlantis. The only way to resolve this issue would be to excavate on the site, but unfortunately, the location is in a national park and at that time any digging was forbidden. Nevertheless, non-intrusive investigative methods were employed to produce additional evidence that might justify a formal archaeological dig. 2010 saw this work begin at the site, with preliminary results indicating that the area was probably hit by a tsunami or a storm flood in the 3rd millennium BC.

The sedimentation argument is not clear-cut, so over a period of millennia when other factors such as seismic activity are brought into the picture, different scenarios are possible. Even if it is not Atlantis or one of its colonies, it would still appear to be a very interesting site, with a story to tell.

In March 2021, Wickboldt published an overpriced 36-page booklet [1822], in which he reprises his contribution to the development of the idea of placing Atlantis in the Doñana Marshes of Andalusia.

(a) “Atlantis lag in Südwest-Spanien” – Atlantisforschung.de (German) *

(b) https://blogs.courant.com/roger_catlin_tv_eye/2011/03/muddying-up-atlantis.html (Link broken March 2020)

.

Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar, José

José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar (1602-1679), a Spanish writer, was probably the  first in 1673[1315] to identify an Andalusian location for Atlantis, proposing that Tartessos was identical with Atlantis and that it was located on the Guadalquivir River in southern Spain near Seville. He specified the Doñana Marshes, where, coincidentally, Kühne and Wickboldt had identified ground features using satellite images, which they claimed corresponded with Plato’s description of Atlantis.

first in 1673[1315] to identify an Andalusian location for Atlantis, proposing that Tartessos was identical with Atlantis and that it was located on the Guadalquivir River in southern Spain near Seville. He specified the Doñana Marshes, where, coincidentally, Kühne and Wickboldt had identified ground features using satellite images, which they claimed corresponded with Plato’s description of Atlantis.

However, subsequent excavation there showed Wickboldt’s images to be smaller than expected or were from the Muslim period. Evidence for Tartessos or Atlantis has not been found.

Schulten, Adolph

Adolph Schulten, (1870-1960), was born in Hamburg, Germany. He was a historian and  archaeologist who rediscovered the ancient Iberian city of Numantia which had been destroyed by the Romans in 134 B.C. and lost for hundreds of years. Schulten was possibly the first to propose, in the early 20th century, that Tarshish mentioned in the Bible was a reference to Tartessos, a cultural centre located in South West Spain and extending across the Strait of Gibraltar into Morocco. He went further and proposed that Tartessos was in fact Atlantis or at least an Atlantean colony.

archaeologist who rediscovered the ancient Iberian city of Numantia which had been destroyed by the Romans in 134 B.C. and lost for hundreds of years. Schulten was possibly the first to propose, in the early 20th century, that Tarshish mentioned in the Bible was a reference to Tartessos, a cultural centre located in South West Spain and extending across the Strait of Gibraltar into Morocco. He went further and proposed that Tartessos was in fact Atlantis or at least an Atlantean colony.

At great personal expense, he spent many years searching for the legendary Tartessos at the mouths of rivers and the cities of Cadiz, Huelva and Seville. However, as Jürgen Spanuth has pointed out, Schulten appears to have dated the demise of Tartessoss to around 500 BC, which was about forty years after Solon’s visit to Egypt, which would imply that Tartessos was not Atlantis.

Schulten wrote a number of articles and books[055], in German, on his investigations. One of his works, Tartessos, in Spanish, can be downloaded from the Internet(a), use your Google translator for English version.

>(a) TARTESSOS.INFO: TARTESSOS DE SCHULTEN (archive.org) (Span) (copy and paste)<