Edward Bacon

Howells, Caleb

Caleb Howells is a British teacher of English with a passion for ancient history. He has already published a book about King Arthur [2077] and next year will offer a new look at the story of Brutus the Trojan king of Britain [2076] in The Trojan Kings of Britain.

Caleb Howells is a British teacher of English with a passion for ancient history. He has already published a book about King Arthur [2077] and next year will offer a new look at the story of Brutus the Trojan king of Britain [2076] in The Trojan Kings of Britain.

Among other publications Howells is also a content writer for the Greek Reporter website, where he has recently endeavoured to revive the ailing Minoan Hypothesis (a)(b).

Plato came from Athens, a city frequently damaged by earthquakes, he also spent time in Sicily where he must have been made aware of the continually active volcano, Mount Etna. Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that Plato could distinguish between an earthquake and a volcano, so when he wrote that Thera had been destroyed by an earthquake, that is what he intended to say. Furthermore, his description of the submergence of Atlantis as a result of the ‘quake sound very much like liquefaction frequently associated with such events. The Minoan Hypothesis does not match Plato’s account.

Although I disagree with Howells identification of Atlantis as Minoan, I was pleasantly surprised that in a December 2023 article(c) he tackled the question of the Pillars of Herakles which included many of the points already published in Atlantipedia. He notes the use of the phrase as a metaphor, particularly by Pindar who used it “as an expression denoting the outermost limit of something. His use of the phrase ‘beyond that the wise cannot set foot’ indicates that he was not merely talking about athletic limits, but limits in general.” Howells also points out the multiplicity of locations designated as ‘Pillars’ and that more than one location were so called at the same time. Nevertheless, he cannot let go of a Minoan connection and so proposed the Gulf of Laconia where the Capes Matapan (Tainaron) and Maleas in the Peloponnese are the two most southerly points of mainland Greece. They have been proposed over forty years ago by Galanopoulos & Bacon [0263] as the Pillars of Heracles when the early Greeks were initially confined to the Aegean Sea and the two promontories were the western limits of their maritime knowledge at that time. Overall, Howells’ article is interesting but unoriginal.

A few days later (12/12/23) he cast doubts on the Capes Matapan and Maleas as the location of the Pillars of Herakles(d). Howells is like a dog with a bone where the Minoan Hypothesis is concerned and and by now should be realising the true complexity of the Atlantis story.

Atlantis was destroyed by submergence following an earthquake, not a volcanic eruption. The Minoans were traders not invaders, so if Crete was Atlantis where is there mention of a war between Athens and the Minoans? Atlantis was a confederation of some sort, so who were its constituents? Why did Plato not simply name the not-too-distant Cretans as the attackers of Athens and laud the victory of the Athenians?

>In late January 2024 Howells expanded his efforts to bolster the Minoan Hypothesis. This time, using some rather convoluted reasoning, he identifies ancient Crete as the Caphtor referred to in the Bible.

This is another contentious issue among historians. The matter is discussed more fully in the Caphtor-Keftiu entry here, where you will find a number of locations identified as Caphtor, including Cyprus, Crete, Cilicia and the Nile Delta. Although currently the most popular would appear to be Crete, Wikipedia seems to favour the Egyptian region of Pelusium(e)!

Cyprus had previously been the most favoured location, about whom Immanuel Velikovsky noted(f) “if Caphtor is not Cyprus, then the Old Tesrament completely omits referenceto this large island close to the Syrian coast.” The Cypriot identification has been endorse by a number of commentators such as John Strange, author of Caphtor/Keftiu: A new Investigation[1052]. I think that with so much controversy surrounding the indentity of the Caphtorim that its possible value as support for the equally controversial Minoan Hypothesis is substantially weakened.

Furthermore, I note that in 2022, Phil Butler published a paper that also suggested identifying the Keftiu as Atlantean(g).<

A number of commentators have supported the idea of Atlantis in the Aegean region. The most convincing, in my opinion, have come from Peter James [047], Eberhard Zangger [483] and more recently Nicholas Costa [2072] , all of whom designated an Anatolian location for Atlantis. They all have their shortcomings but have built stronger cases than Howells for their chosen locations.

(a) Was Atlantis’ Temple of Poseidon the Palace of Knossos in Crete? (greekreporter.com)

(b) Was Atlantis a Minoan Civilization on Santorini Island? (greekreporter.com)

(c) https://greekreporter.com/2023/12/07/pillars-hercules-greek-mythology/

(d) https://greekreporter.com/2023/12/12/mythical-atlantis-located/

(e) Caphtor – Wikipedia *

(f) Ages in Chaos p.210 n.79 *

(g) The Keftiu: Were They Absorbed and Erased from History? (argophilia.com) *

Finley, Moses I.

Moses I. Finley, originally Finkelstein (1912–1986) was an American-born British academic. He moved to England in 1955, where he developed as a classical scholar and eventually became Master of Darwin College, Cambridge. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1979.

In common with a number of archaeologists and historians at the time, Finley maintained that none of the events in Homer’s works are historical, particularly in his book, The World of Odysseus [1139] and was highly critical of Michael Wood’s In Search of the Trojan War [1141] when it first appeared in 1984, four years before modern archaeology was undertaken at the Hissarlik site.(a)

>Finley in chapter two of his Aspects of Antiquity [1953] listed a number of weaknesses in Schliemann’s identification of Hissarlik as Homer’s Troy. Some of his more important points are summarized here(f).

“Schliemann’s “Troy” site had been over the ages razed and rebuilt many times, and the various rebuildings are commonly referred to by numbered names such as “Troy I” or “Troy VIIa”.

Schliemann’s “Troy” site has only one stage of its history that has any resemblance to Greece. That is Troy VIIa, which contains pottery shards and other evidence that it had contact with Greece. All the other “Troy” ruins at Schliemann’s site have no remains that even suggest they ever had contact with the greeks.

Troy VIIa is actually one of the smallest constructions at Schliemann’s “Troy” site. To quote Finley: ‘a shabby, impoverished huddled in one small sector of the ridge, as unlike the Homeric picture of the large and wealthy city of Priam as one could imagine.’

Schliemann’s great treasures which are held to prove his site was a country of vast power and influence, were found at Troy II. Troy II dates to 2500-2200 bc, long predating the greeks.

In fact, Finley contends on pages 37-38 of his book that our historical concept of the greeks of the Homeric age being a continental power capable of staging such a massive expedition is based wholely upon the description of it as such in The Illiad, and not upon archaeological evidence from the greek civilizations of the Homeric era. In other words, rather than the undeniable existence of the Achaean empire serving as proof of the events depicted in Homer, instead, the existence of the Achaean Greek empire is based solely upon its being mentioned in The Illiad

There are no surviving written records of the Achaeans or Trojans from the Homeric era. Both the Egyptians and the Hittites did keep historical records, legal documents, treaties, etc, that have survived for modern archaeologists to translate. Neither the Hittites nor the Pharaohs make any reference to the Achaeans or the Trojans.”<

Finley’s sceptical views went beyond the Trojan War and extended to Plato’s Atlantis. In 1969, a number of books and papers were published giving added impetus to the Minoan Hypothesis. Finley attacked James W. Mavor‘s Voyage to Atlantis [265] in The New York Review of Books (b). This evoked a response(c) from Mavor not long afterward.

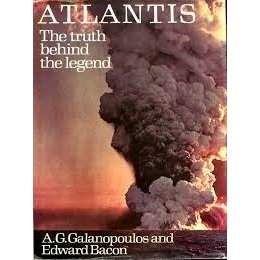

In December 1969, Finley wrote a combined critical review of both Atlantis [263] by Galanopoulos & Bacon as well as J. V. Luce‘s Lost Atlantis(U.S) (The End of Atlantis, U.K.) [120] for the same publication(d), to which Galanopoulos also responded(e).

(a) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historicity_of_the_Homeric_epics

(b) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(c) https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1969/12/04/back-to-atlantis-again/

(d) Back to Atlantis | by M.I. Finley | The New York Review of Books (archive.org)

(e) The End of Atlantis | by A.G. Galanopoulos | The New York Review of Books (archive.org)

Matapan & Maleas, Capes

Capes Matapan (Tainaron) and Maleas in the Peloponnese are the two most southerly points of mainland Greece. They have been proposed by Galanopoulos & Bacon [0263] as the Pillars of Heracles, when the early Greeks were initially confined to the Aegean Sea and the two promontories were the western limits of their maritime knowledge.>They note that

“This has been the subject of some interesting conjectures. Nearly all the labours of Hercules were performed in the Peloponnese. The last and hardest of those which Eurytheus imposed on the hero was to descend to Hades and bring back its three-headed dog guardian, Cerberus. According to the most general version Hercules entered Hades through the abyss at Cape Taenarun (the modern Cape Matapan), the Western cape of the Gulf of Laconia. The Eastern cape of this gulf is Cape Maleas, a dangerous promontory, notorious for its rough seas.

Pausanias records that on either side of this windswept promontory were temples, that on the west dedicated to Poseidon, that on the east to Apollo. It is perhaps therefore not extravagant to suggest that the Pillars of Hercules referred to are the promontories of Taenarum and Maleas; and it is perhaps significant that the twin brother of Atlas was allotted the extremity of Atlantis closest to the Pillars of Hercules. The relevant passage in the Critias (114A-B) states:

‘And the name of his younger twin-brother, who had for his portion the extremity of the island near the pillars of Hercules up to the part of the country now called Gadeira after the name of that region, was Eumelus in Greek, but in the native tongue Gadeirus — which fact may have given its title to the country.’

Since the region had been named after the second son of Poseidon, whose Greek name was Eumelus, its Greek title must likewise have been Eumelus, a name which brings to mind the most westerly of the Cyclades, Melos, which is in fact not far from the notorious Cape Maleas. The name Eumelus was in use in the Cyclades; and the ancient inscription (‘Eumelus an excellent danger’) was found on a rock on the island of Thera.

In general, it can be argued from a number of points in Plato’s narrative that placing ‘the Pillars of Hercules’ at the south of the Peloponnese makes sense, while identifying them with the Straits of Gilbraltar does not[p.97].”<

Current, Ron

Ron Current is an American blogger with a passion for travel, history and photography. Beginning in March 2016 he has written a number of pieces(a) on Atlantis and has concluded that Thera (Santorini) and its 2nd millennium BC eruption was at least part of the inspiration behind Plato’s narrative.

Ron Current is an American blogger with a passion for travel, history and photography. Beginning in March 2016 he has written a number of pieces(a) on Atlantis and has concluded that Thera (Santorini) and its 2nd millennium BC eruption was at least part of the inspiration behind Plato’s narrative.

He echoes the views of Galanopoulos & Bacon[0263] regarding the location of the Pillars of Heracles saying “There are two landmasses in the world of these ancient Greeks that were also called the Pillars of Heracles in that period. These are the two southward pointing headlands on each side of the Gulf of Laconia on Greece’s Peloponnese.” These would have been Capes Matapan and Maleas. This, of course, contradicts Plato’s clear statement that Atlantis attacked from the west, not the south.*In fact what Plato said was that the invasion came from the Atlantic Sea (pelagos). Although there is some disagreement about the location of this Atlantic Sea, all candidates proposed so far are west of both Athens and Egypt.*

(a) https://stillcurrent.wordpress.com/2016/04/05/atlantis-maybe-not-so-lost/

Tschoegl, Nicholas William

Nicholas William Tschoegl (1918-2011) was born in what is now an eastern  part of the Czech Republic. He was educated in Europe and after the Second World War his family fled to Australia and later to USA where he became a Professor of Chemical Engineering, although pursuing additional interests in ancient civilisation and the development of writing. He has also lectured on Atlantis supporting the idea of Minoan Crete and Thera as its possible location(a).*He follows Galanopoulos & Bacon in subscribing to the ‘factor ten’ hypothesis to reconcile Plato’s apparent date for the Atlantean war with the eruption of Thera.*

part of the Czech Republic. He was educated in Europe and after the Second World War his family fled to Australia and later to USA where he became a Professor of Chemical Engineering, although pursuing additional interests in ancient civilisation and the development of writing. He has also lectured on Atlantis supporting the idea of Minoan Crete and Thera as its possible location(a).*He follows Galanopoulos & Bacon in subscribing to the ‘factor ten’ hypothesis to reconcile Plato’s apparent date for the Atlantean war with the eruption of Thera.*

(a) https://calteches.library.caltech.edu/307/1/atlantis.pdf

Minoan Hypothesis

The Minoan Hypothesis proposes an Eastern Mediterranean origin for Plato’s Atlantis centred on the island of Thera and/or Crete. The term ‘Minoan’ was coined by the renowned archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the mythic King Minos. (Sir Arthur was the son of another well-known British archaeologist, Sir John Evans). Evans thought that the Minoans had originated in Northern Egypt and came to Crete as refugees. However, recent genetic studies seem to indicate a European ancestry!

It is claimed(a) that Minoan influence extended as far as the Iberian Peninsula as early as 3000 BC and is reflected thereby what is now known as the Los Millares Culture. Minoan artefacts have also been found in the North Sea, but it is not certain if they were brought there by Minoans themselves or by middlemen. The German ethnologist, Hans Peter Duerr, has a paper on these discoveries on the Academia.edu website(e). He claims that the Minoans reached the British Isles as well as the Frisian Islands where he found artefacts with some Linear A inscriptions near the site of the old German trading town of Rungholt, destroyed by a flood in 1362(f).

The advanced shipbuilding techniques of the Minoans are claimed to have been unmatched for around 3,500 years until the 1950s (l).

The Hypothesis had its origin in 1872 when Louis Guillaume Figuier was the first to suggest [0296] a link between the Theran explosion and Plato’s Atlantis. The 1883 devastating eruption of Krakatoa inspired Auguste Nicaise, in an 1885 lecture(c) in Paris, to cite the destruction of Thera as an example of a civilisation being destroyed by a natural catastrophe, but without reference to Atlantis.

The Minoan Hypothesis proposes that the 2nd millennium BC eruption(s) of Thera brought about the destruction of Atlantis. K.T. Frost and James Baikie, in 1909 and 1910 respectively, outlined a case for identifying the Minoans with the Atlanteans, decades before the extent of the massive 2nd millennium BC Theran eruption was fully appreciated by modern science. In 1917, Edwin Balch added further support to the Hypothesis [151].

As early as April 1909, media speculation was already linking the discoveries on Crete with Atlantis(h), despite Jowett’s highly sceptical opinion.

Supporters of a Minoan Atlantis suggest that when Plato wrote of Atlantis being greater than Libya and Asia he had mistranscribed meison (between) as meizon (greater), which arguably would make sense from an Egyptian perspective as Crete is between Libya and Asia, although it is more difficult to apply this interpretation to Thera which is further north and would be more correctly described as being between Athens and Asia. Thorwald C. Franke has now offered a more rational explanation for this disputed phrase when he pointed out [0750.173] that “for Egyptians, the world of their ‘traditional’ enemies was divided in two: To the west, there were the Libyans, to the east there were the Asians. If an Egyptian scribe wanted to say, that an enemy was more dangerous than the ‘usual’ enemies, which was the case with the Sea Peoples’ invasion, then he would have most probably said, that this enemy was “more powerful than Libya and Asia put together”.

It has been ‘received wisdom’ that the Minoans were a peace-loving people, however, Dr Barry Molloy of Sheffield University has now shown that the exact opposite was true(d) and that “building on recent developments in the study of warfare in prehistoric societies, Molloy’s research reveals that war was, in fact, a defining characteristic of the Minoan society, and that warrior identity was one of the dominant expressions of male identity.”

In 1939, Spyridon Marinatos published, in Antiquity, his opinion that the eruption of Thera had led to the demise of the Minoan civilisation. However, the editors forbade him to make any reference to Atlantis. In 1951, Wilhelm Brandenstein published a Minoan Atlantis theory, echoing many of Frost’s and Marinatos’ ideas, but giving little credit to either.

However, Colin MacDonald, an archaeologist at the British School in Athens, believes that “Thira’s eruption did not directly affect Knossos. No volcanic-induced earthquake or tsunami struck the palace which, in any case, is 100 meters above sea level.” The Sept. 2019 report in Haaretz suggests it’s very possible the Minoans were taken over by another civilization and may have been attacked by the Mycenaeans, the first people to speak the Greek language and they flourished between 1650 B.C. and 1200 B.C. Archaeologists believe that the Minoan and Mycenaean civilisations gradually merged, with the Mycenaeans becoming dominant, leading to the shift in the language and writing system used in ancient Crete.

The greatest proponents of the Minoan Hypothesis were arguably A.G. Galanopoulos and Edward Bacon. Others, such as J.V. Luce and James Mavor were impressed by their arguments and even Jacques Cousteau, who unsuccessfully explored the seas around Santorini, while Richard Mooney, the ‘ancient aliens’ writer, thought [0842] that the Minoan theory offered a credible solution to the Atlantis mystery. More recently Elias Stergakos has proposed in an overpriced 68-page book [1035], that Atlantis was an alliance of Aegean islands that included the Minoans.

Moses Finley, the respected classical scholar, wrote a number of critical reviews of books published by prominent supporters of the Minoan Hypothesis, namely Luce(aa), Mavor(y)(z) as well as Galanopoulos & Bacon(aa)(ab). Some responded on the same forum, The New York Review of Books.

Andrew Collins is also opposed to the Minoan Hypothesis, principally because “we also know today that while the Thera eruption devastated the Aegean and caused tsunami waves that destroyed cities as far south as the eastern Mediterranean, it did not wipe out the Minoan civilization of Crete. This continued to exist for several generations after the catastrophe and was succeeded by the later Mycenaean peoples of mainland Greece. For these reasons alone, Plato’s Atlantic island could not be Crete, Thera, or any other place in the Aegean. Nor can it be found on the Turkish mainland at the time of Thera’s eruption as suggested by at least two authors (James and Zangger) in recent years(ad).“

Alain Moreau has expressed strong opposition to the Minoan Hypothesis in a rather caustic article(i), probably because it conflicts with his support for an Atlantic location for Atlantis. In more measured tones, Ronnie Watt has also dismissed a Minoan Atlantis, concluding that “Plato’s Atlantis happened to become like the Minoan civilisation on Theros rather than to be the Minoan civilisation on Theros.” In 2001, Frank Joseph wrote a dismissive critique of the Minoan Hypothesis referring to Thera as an “insignificant Greek island”.(x)

Further opposition to the Minoan Hypothesis came from R. Cedric Leonard, who has listed 18 objections(q) to the identification of the Minoans with Atlantis, keeping in mind that Leonard is an advocate of the Atlantic location for Plato’s Island.

Atlantisforschung has highlighted Spanuth’s opposition to the Minoan Hypothesis in a discussion paper on its website. I have published here a translation of a short excerpt from Die Atlanter that shows his disdain for the idea of an Aegean Atlantis.

“Neither Thera nor Crete lay in the ‘Atlantic Sea’, but in the Aegean Sea, which is expressly mentioned in Crit. 111a and contrasted with the Atlantic Sea. Neither of the islands lay at the mouth of great rivers, nor did they “sink into the sea and disappear from sight.” ( Tim. 25d) The Aegean Sea never became “impassable and unsearchable because of the very shallow mud”. Neither Solon nor Plato could have said of the Aegean Sea that it was ‘still impassable and unsearchable’ or that ‘even today……….an impenetrable and muddy shoal’ ‘blocks the way to the opposite sea (Crit.108e). Both had often sailed the Aegean Sea and their contemporaries would have laughed at them for telling such follies.” (ac)

Lee R. Kerr is the author of Griffin Quest – Investigating Atlantis [0807], in which he sought support for the Minoan Hypothesis. Griffins (Griffons, Gryphons) were mythical beasts in a class of creatures that included sphinxes. Kerr produced two further equally unconvincing books [1104][1675], all based on his pre-supposed link between Griffins and Atlantis or as he puts it “whatever the Griffins mythological meaning, the Griffin also appears to tie Santorini to Crete, to Avaris, to Plato, and thus to Atlantis, more than any other single symbol.” All of which ignores the fact that Plato never referred to a Sphinx or a Griffin!

The hypothesis remains one of the most popular ideas with the general public, although it conflicts with many elements in Plato’s story. A few examples of these are, where were the Pillars of Heracles? How could Crete/Thera support an army of one million men? Where were the elephants? There is no evidence that Crete had walled cities such as Plato described. The Minoan ships were relatively light and did not require the huge harbours described in the Atlantis story. Plato describes the Atlanteans as invading from their western base (Tim.25b & Crit.114c); Crete/Santorini is not west of either Egypt or Athens

Gavin Menzies attempted to become the standard-bearer for the Minoan Hypothesis. In The Lost Empire of Atlantis [0780], he argues for a vast Minoan Empire that spread throughout the Mediterranean and even discovered America [p.245]. He goes further and claims that they were the exploiters of the vast Michigan copper reserves, which they floated down the Mississippi for processing before exporting it to feed the needs of the Mediterranean Bronze industry. He also accepts Hans Peter Duerr’s evidence that the Minoans visited Germany, regularly [p.207].

Tassos Kafantaris has also linked the Minoans with the exploitation of the Michigan copper, in his paper, Minoan Colonies in America?(k) He claims to expand on the work of Menzies, Mariolakos and Kontaratos. Another Greek Professor, Minas Tsikritsis, also supports the idea of ancient Greek contact with America. However, I think it is more likely that the Minoans obtained their copper from Cyprus, whose name, after all, comes from the Greek word for copper.

Oliver D. Smith has charted the rise and decline in support for the Minoan Hypothesis in a 2020 paper entitled Atlantis and the Minoans(u).

Frank Joseph has criticised [0802.144] the promotion of the Minoan Hypothesis by Greek archaeologists as an expression of nationalism rather than genuine scientific enquiry. This seems to ignore the fact that Figuier was French, Frost, Baikie and Bacon were British, Luce was Irish and Mavor was American. Furthermore, as a former leading American Nazi, I find it ironic that Joseph, a former American Nazi leader, is preaching about the shortcomings of nationalism.

While the suggestion of an American connection may seem far-fetched, it would seem mundane when compared with a serious attempt to link the Minoans with the Japanese, based on a study(o) of the possible language expressed by the Linear A script. Gretchen Leonhardt(r) also sought a solution in the East, offering a proto-Japanese origin for the script, a theory refuted by Yurii Mosenkis(s), who promotes Minoan Linear A as proto-Greek. Mosenkis has published several papers on the Academia.edu website relating to Linear A(t). However, writing was not the only cultural similarity claimed to link the Minoans and the Japanese offered by Leonhardt.

Furthermore, Crete has quite clearly not sunk beneath the waves. Henry Eichner commented, most tellingly, that if Plato’s Atlantis was a reference to Crete, why did he not just say so? After all, in regional terms, ‘it was just down the road’. The late Philip Coppens was also strongly opposed to the Minoan Hypothesis.(g)

Eberhard Zangger, who favours Troy as Atlantis, disagrees strongly [0484] with the idea that the Theran explosion was responsible for the 1500 BC collapse of the ‘New Palace’ civilisation.

Excavations on Thera have revealed very few bodies resulting from the 2nd millennium BC eruptions there. The understandable conclusion was that pre-eruption rumblings gave most of the inhabitants time to escape. Later, Therans founded a colony in Cyrene in North Africa, where you would expect that tales of the devastation would have been included in their folklore. However, Eumelos of Cyrene, originally a Theran, opted for the region of Malta as the remnants of Atlantis. How could he have been unaware of the famous history of his family’s homeland?

A 2008 documentary, Sinking Atlantis, looked at the demise of the Minoan civilisation(b). James Thomas has published an extensive study of the Bronze Age, with particular reference to the Sea Peoples and the Minoans(j).

In the 1990s, art historian and museum educator, Roger Dell, presented an illustrated lecture on the art and religion of the Minoans titled Art and Religion of the Minoans: Europe’s first civilization”, which offered a new dimension to our understanding of their culture(p). In this hour-long video, he also touches on the subject of Atlantis and the Minoans.

More extreme is the theory of L. M. Dumizulu, who offers an Afrocentric view of Atlantis. He claims that Thera was part of Atlantis and that the Minoans were black!(m)

In 2019, Nick Austin attempted [1661] to add further support to the idea of Atlantis on Crete, but, in my opinion, he failed. The following year, Sean Welsh also tried to revive the Minoan Hypothesis in his book Apocalypse [1874], placing the Atlantean capital on Santorini, which was destroyed when the island erupted around 1600 BC. He further claims that the ensuing tsunami led to the biblical story of the Deluge.

Evan Hadingham published a paper(v) in 2008 in which he discussed the possibility that the Minoan civilisation was wiped out by the tsunami generated by the eruption(s) of Thera. Then, seven years later he produced a second paper(w) exonerating the tsunami based on new evidence or lack of it.

In April 2023, an attempt was made to breathe some new life into the Minoan Hypothesis in an article(ae) on the Greek Reporter website. This unconvincing piece claims “Plato describes in detail the Temple of Poseidon on Atlantis, which appears to be identical to the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete.” The writer, Caleb Howells, has conveniently overlooked that Atlantis was submerged creating dangerous shoals and remained a maritime hazard even up to Plato’s day (Timaeus 25d). The Knossos Palace is on a hill and offers no evidence of ever having been submerged. Try again.

The same reporter did try again with another unconvincing piece supporting the Minoan Hypothesis, also on the Greek Reporter site, in October 2023(af). This time, he moved the focus of his claim to Santorini where he now placed the Palace of Poseidon relocating it from Crete! I suppose he will eventually make his mind up. Nevertheless, Howells revisited the subject of the Palace of Poseidon just a few weeks later, once again identifying it as the Palace of Knossos – “Plato’s account of the lost civilization of Atlantis includes a description of a marvelous temple of god Poseidon. It was said to have been in the center of Atlantis, so it was a very prominent part. However, in most investigations into the origin of Atlantis, this detailed temple description is ignored. In fact, an analysis of Plato’s details indicates that the Temple of Poseidon on Atlantis was actually identical to the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete, Greece.” (ag)

Most Atlantis theories manage to link their their chosen site with some of the descriptive details provided by Plato. The Minoan Hypothesis is no exception, so understandably Howells has highlighted the similarities, while ignoring disparities. The Minoans were primarily concerned with trading, not territorial expansion. When did they engage in a war with Athens or threaten Egypt? If Howells can answer that he may have something relevant to build upon!

>For a useful backdrop to the Minoan civilisation I suggest that readers have a look at a fully illustrated 2019 lecture by Dr. Gregory Mumford of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In it he give a broad overview of the Eastern Mediterranean, with a particular emphasis on the Aegean Sea, during the Middle- Late Bronze Age (2000-1200 BC). (ah) <

(a) http://www.minoanatlantis.com/Minoan_Spain.php

(b) http://video.pbs.org/video/1204753806/

(c) http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Les_Terres_disparues

(d) http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/article00826.html

(e) See: Archive 3928

(f) http://dienekes.blogspot.ie/2008/08/minoans-in-germany.html

(g) https://web.archive.org/web/20180128190713/http://philipcoppens.com/lectures.php (June 3, 2011)

(j) https://medium.com/the-bronze-age

(k) https://www.scribd.com/document/161156089/Minoan-Colonies-in-America

(m) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QqTQeF2gLpg

(o) Archive 3930 | (atlantipedia.ie)

(p) https://vimeo.com/205582944 Video

(q) https://web.archive.org/web/20170113234434/http://www.atlantisquest.com/Minoan.html

(r) https://konosos.net/2011/12/12/similarities-between-the-minoan-and-the-japanese-cultures/

(t) https://www.academia.edu/31443689/Researchers_of_Greek_Linear_A

(u) https://www.academia.edu/43892310/Atlantis_and_the_Minoans

(v) Did a Tsunami Wipe Out a Cradle of Western Civilization? | Discover Magazine

(w) https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/megatsunami-may-wiped-europes-first-great-civilization/

(x) Atlantis Rising magazine #27 http://pdfarchive.info/index.php?pages/At

(y) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(z) https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1969/12/04/back-to-atlantis-again/

(aa) Back to Atlantis | by M.I. Finley | The New York Review of Books (archive.org)

(ab) The End of Atlantis | by A.G. Galanopoulos | The New York Review of Books (archive.org)

(ac) Jürgen Spanuth über ‘Atlantis in der Ägäis’ – Atlantisforschung.de

(ad) Kreta oder Thera als Atlantis? – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(ae) Was Atlantis’ Temple of Poseidon the Palace of Knossos in Crete? (greekreporter.com)

(af) Was Atlantis a Minoan Civilization on Santorini Island? (greekreporter.com)

(ag) https://greekreporter.com/2023/12/01/atlantis-temple-poseidon-palace-knossos-crete/

Kings of Atlantis

The Kings of Atlantis were, according to Plato, originally the sons of Poseidon and Cleito. They were ten in number and consisted of five sets of male twins. The firstborn was Atlas who was given authority over the others, each of whom controlled their own territory. Some commentators reacted with such incredulity to this story, that they have either dismissed this detail or in some cases the entire Atlantis tale as pure fantasy. Of course, it is highly improbable, if not virtually impossible to accept that Clieto had five sets of all-male twins. However, we are dealing here with a myth that is an echo of the legends of many other cultures describing their antediluvian origins. Lenormant & Chevallier wrote [424] of this over a hundred years ago:

“…The ten kingdoms of Atlantis are perpetuated in all the ancient traditions. ‘In the number given by the Bible for the Antediluvian patriarchs we have the first instance of a striking agreement with the traditions of various nations. Other nations, to whatever epoch they carry back their ancestors…are constant to the sacred number of ten… In Chaldea (Babylon), Berosus, writing in the third century BC, numerates ten Antediluvian kings whose fabulous reigns extended to thousands of years. The legends of the Iranian race commence with the reign of ten Peisdadien (Poseidon?) kings…. In India we meet with the nine Brahmadikas, who, with Brahma, their founder, make ten, and who are called the Ten Petris, or Fathers. The Chinese count ten emperors, partaking of the divine nature, before the dawn of historical time. The Germans believed in the ten ancestors of Odin, and the Arabs in the ten mythical kings of the Adites”.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, in the 6th century AD, contended[1245] that Atlantis was the Garden of Eden and that Plato’s 10 kings of Atlantis were the 10 generations between Adam and Noah!

It may be just a coincidence, but Plato tells us that the domain of Atlantis extended as far as Tyrrhenia (modern Tuscany), just south of which was Rome, a city, which according to legend was also founded by twin brothers, Romulus and Remus. It has been claimed that the story of their origins is a variation of the story in the Hindu epic Ramayana concerning the twin sons of king Sri Rama, Luva and Kusha(c).

In the same region, Sicily has the legend of the divine Palici twins (Palikoi in Greek).

>Aelian in his Natura Animalium has recorded [0619 xv.2] how the natives who live on the shores of ‘Ocean’ have a legend that tells of the Atlantean kings, who, to symbolise their authority from Poseidon, wore a crown reminiscent of the white band that ran around the forehead of the male ‘ram fish’ while their queens wore headgear made from the skins of ’marine ewes’.

“Ram-fishes, whose name has a wide circulation, although information about them is not very definite except in so far as displayed in works of art, spend the winter near the strait between Corsica and Sardinia and actually appear above water. And round about them swim dolphins of very great size.” (15.2)(f)

Although these animals have not been clearly identified, their size suggests a species of whale. I suggest that it was a fin whale which has a grey or white chevron marking on top of its head and is frequently found in the Strait of Bonifacio, between Corsica and Sardinia, at the southern end of the Pelagos Sanctuary.

“Fin whales, the second largest animal on the planet after blue whales, are represented in the Mediterranean by a resident population separated from the Atlantic.“(e)

So, it would appear obvious from this excerpt that Aelian did not have any doubt regarding the reality of Atlantis. Perhaps even more interesting is that Aelian seems to also associate these kings of Atlantis with Corsica and Sardinia. For me, this is compatible with a Central Mediterranean location for Atlantis.<

Although Babylon is supposed to have had ten kings before the Flood, it must be noted that they reigned successively rather than concurrently, as was the case in Atlantis.

Attention has been drawn to the fact that Manetho (c. 300 BC), the Egyptian historian called the first sequence of Egyptian god-kings ‘Auriteans’, which has been seen as suspiciously like a corruption of ‘Atlanteans‘.

Plato gives the names of the first ten kings as; Atlas, Gadeiros (Eumelos), Ampheres, Euaimon, Mneseos, Autochthon, Elasippos, Mestor, Azaes, Diaprepres (Critias 114b).

Some writers have attempted to link these names with specific regions; such as Atlas with Morocco, Eumelos (Gadeiros) with Gades (Cadiz) and Elasippos with Lisbon. Beyond these three there is very little agreement. Lewis Spence correctly points out “Plato expressly states that these names had been Egyptianised from the Atlantean language by the priest of Sais, and subsequently Hellenised in Critias, so that there is little hope that they were transmitted in anything like their original form.” Spence also commented on the similarity of the Phoenician gods and the early kings of Atlantis, an idea suggested earlier by Ignatius Donnelly.

Reginald Fessenden claimed to have identified at least six of Plato’s Atlantean king-list with names in the Caucasus.(d)

Even more distant locations were proposed by the French cartographer Guillaume Sanson (1633-1703), who generously distributed the Americas among the ten brothers, allocating Mexico to Atlas.

R. Cedric Leonard is convinced that Manetho’s list of Egyptian god-kings is in fact a list of the first kings of Atlantis and expands on this idea on his website(a). However, in his 1979 book, Quest for Atlantis[0130], Leonard has suggested that the kings of Atlantis were human-alien hybrids and that humans are the result of alien genetic experiments!!

Another site(b) identifies the kings of Atlantis with the pantheon of Phoenician gods, an idea first mooted by Ignatius Donnelly (part IV. chap. III). But Donnelly, also suggested, unconvincingly, that the gods of the Greeks were just the deified kings of Atlantis (part IV, chap. II), while it is also possible that they were just personifications of natural phenomena.

An unusual feature of the Atlantean kings is the meeting every fifth and sixth year. Plato explains this as a way of honouring odd and even numbers. However, Bacon & Galanopoulos suggest[263.152] that in fact, this may have been the result of an awareness of the eleven-year cycles of rains. I believe that this explanation is equally weak and the subject requires further investigation.

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20170608084749/http:/www.atlantisquest.com:80/Hiero.html

(b) https://phoenicia.org/godidea.html#Atlantis

(c) https://vediccafe.blogspot.ie/2014/05/the-ramayana-in-roots-of-pre-christian.html

(d) The Deluged Civilisation of the Caucasus Isthmus [1012] (chap 3.29) *

(e) https://tethys.org/activities-overview/research/fin-whales/ *

Bacon, Edward

Edward Bacon (1906-1981) was the archaeological editor of the Illustrated London News for many years, who also wrote a number of books of his own[139] and edited others, on the subject of archaeology.

In 1961 he published Digging for History which is a review of important archaeological excavations worldwide from 1945 to 1959.

He was the co-author with Angelos Georgiou Galanopoulos of Atlantis, The Truth Behind the Legend[263] which generated renewed interest in the Minoan Hypothesis after its publication in 1969. The basis for their theory is a belief that Plato’s 9,000 years for the time elapsed since the Atlantean War is overstated by a factor of 10. If this were correct, 900 years would bring the date of its demise in line with the date of the massive eruption of Thera. However, there are a number of weaknesses with this association that are discussed elsewhere.

Atlantis: The Truth behind the Legend

Atlantis: The Truth behind the Legend [263] by Angelos Georgiou Galanopoulos and Edward Bacon supports Thera, modern Santorini, as the location of Atlantis. Their starting point was a re-appraisal of Plato’s date of 9,000 years from the time of the attack on Athens & Egypt to the time of Solon. They proposed that there had been a mistranslation from the Egyptian records and that this should in fact have read nine hundred years (see Date of Atlantis Collapse). This would place the demise of Atlantis around 1500 BC. They then linked the cataclysmic eruption of Thera with this date and proceeded to build a case for identifying this event with the destruction of Atlantis. A number of inconsistencies between their theory and the details of Plato’s narrative have been pointed out; Thera was never large enough to accommodate the extensive plain of Atlantis, the location of the Pillars of Heracles, the original island was too small to support a viable population of elephants, the size of the Atlantean army and navy at around one million men, not to mention an even greater civilian population could not have been housed on tiny Thera, etc, etc. When these difficulties are added to the authors’ arbitrary re-dating of the sinking of Atlantis, a Theran solution is untenable, unless the detailed descriptions given by Plato can be set aside as just a fictional overlay. However, the idea of Atlantis being connected with the 2nd millennium BC eruption of Thera is widely accepted and has done no harm to the tourist industry of Santorini.

Atlantis: The Truth behind the Legend [263] by Angelos Georgiou Galanopoulos and Edward Bacon supports Thera, modern Santorini, as the location of Atlantis. Their starting point was a re-appraisal of Plato’s date of 9,000 years from the time of the attack on Athens & Egypt to the time of Solon. They proposed that there had been a mistranslation from the Egyptian records and that this should in fact have read nine hundred years (see Date of Atlantis Collapse). This would place the demise of Atlantis around 1500 BC. They then linked the cataclysmic eruption of Thera with this date and proceeded to build a case for identifying this event with the destruction of Atlantis. A number of inconsistencies between their theory and the details of Plato’s narrative have been pointed out; Thera was never large enough to accommodate the extensive plain of Atlantis, the location of the Pillars of Heracles, the original island was too small to support a viable population of elephants, the size of the Atlantean army and navy at around one million men, not to mention an even greater civilian population could not have been housed on tiny Thera, etc, etc. When these difficulties are added to the authors’ arbitrary re-dating of the sinking of Atlantis, a Theran solution is untenable, unless the detailed descriptions given by Plato can be set aside as just a fictional overlay. However, the idea of Atlantis being connected with the 2nd millennium BC eruption of Thera is widely accepted and has done no harm to the tourist industry of Santorini.

The authors also introduce the idea of two islands, each with its own adjacent plain, one of which is quite small and the other quite extensive, supposedly Thera and Crete. However, if Plato was speaking of Thera and Crete, why did he not say so? Any serious reading of Plato’s text shows that he was not exactly sure where Atlantis had been.

Humboldt, Alexander Freiherr von *

Alexander Freiherr von Humboldt (1769-1859) was a renowned German scientist and explorer. He spent five years (1799-1804) on an expedition to South America. While there he discovered the Casiquiare River, which links the Amazon and Orinoco rivers.

Humboldt expressed the view that Atlantis had possibly been located in America, although in his 1814 book, Personal Narrative of Travels[1329.v1.201], he stated that he did “not intend to form any opinion in favour of the existence of the Atlantis.”

Humboldt also considered the likelihood of ancient links between Europe and the Americas, pointing out remarkable similarities between the Nahuatl and Greek languages. An example of which is the Aztecan Nahuatl language’s teo-cali (god’s house) and the Greek theoukalia (shrine or god’s house).

Furthermore, Humboldt also claimed that the Mayan and ancient Chinese calendars had a common source, an idea adopted by David H. Kelley in a paper written decades ago, but only recently published in the journal Pre-Columbiana. A review of his work by Tara MacIsaac in Epoch Times(b) should also be read. Jason Colavito has offered a sceptical view of that claim(a).

However, Galanopoulos and Bacon assert[263.96] that Humboldt favoured a Mediterranean inspiration for the Atlantis drama.

(b) Mayan Calendar Similar to Ancient Chinese: Early Contact? (archive.org) *