Philo of Alexandria

Italy

Italy seems to have an uncertain etymology; Thucydides claims that Italos, the Sicilian king gave his name to Italy, while more recently Emilio Spedicato(h) considers that ”the best derivation we believe to be the one proposed by the Italian nuclear engineer Felice Vinci (1998), in his monograph claiming a Baltic setting for the Homeric epic: he derives Italia from the rare Greek word aithalia, meaning the smoking one.” This is thought to be a reference to Italy’s many volcanoes.

Italy today is comprised of territory south of the Alps on mainland Europe including a very large boot-shaped peninsula, plus Sicily, Sardinia and some smaller island groups, which along with the French island of Corsica virtually enclose the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The earliest proposal that Italy could be linked with Atlantis came from Angelo Mazzoldi in 1840 when he claimed that before Etruria, Italy had been home to Atlantis and dated its demise to 1986 BC. Mazzoldi expressed a form of hyperdiffusion that had his Italian Atlantis as the mother culture which seeded the great civilisations of the eastern Mediterranean region(b).

Some of Mazzoldi’s views regarding ancient Italy were expanded on by later scholars such as Camillo Ravioli, Ciro Nispi-Landi, Evelino Leonardi, Costantine Cattoi, Guido DiNardo and Giuseppe Brex. Ravioli sought to associate the Maltese island of Gozo with his proposed Atlantis in Italy.

The Italian region of Lazio, which includes Rome, has had a number of very ancient structures proposed as Atlantean; Monte Circeo (Leonardi) and Arpino(a) (Cassaro). Another aspect of Italian prehistory is the story of Tirrenide, which was described as a westward extension of the Italian landmass into the Tyrrhenian Sea during the last Ice Age, with a land bridge to a conjoined Sardinia and Corsica. At the same time, there were land links to Sicily and Malta, which were all destroyed as deglaciation took place and sea levels rose.

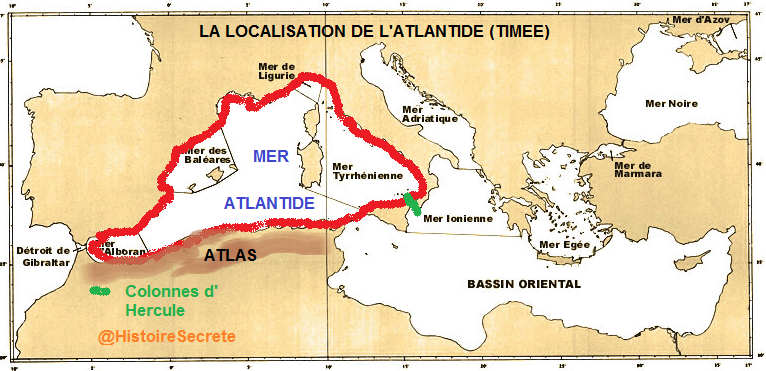

It is surprising that so few researchers have commented on Italy’s part in Plato’s Atlantis narrative considering that he twice, without any ambiguity, informs us that the Atlantean domain extended as far as Tyrrhenia (modern Tuscany).

It is surprising that so few researchers have commented on Italy’s part in Plato’s Atlantis narrative considering that he twice, without any ambiguity, informs us that the Atlantean domain extended as far as Tyrrhenia (modern Tuscany).

Crit.114c. So all these, themselves and their descendants dwelt for many generations bearing rule over many other islands throughout the sea and holding sway besides, as was previously stated, over the Mediterranean peoples as far as Egypt and Tuscany. Tim.25a/b. Now in this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvellous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent; and, moreover, of the lands here within the Straits they ruled over Libya as far as Egypt, and over Europe as far as Tuscany. (Bury)

The quotation from Timaeus is most interesting because of its reference to a ‘continent’. Some have understandably but incorrectly claimed that this is a reference to America or Antarctica, when quite clearly it refers to southern Italy as part of the continent of Europe. Moreover, Herodotus is quite clear (4.42) that the ancient Greeks knew of only three continents, Europe, Asia and Libya.

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(g) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139).>The name ‘Italy’ was normally used until the third century BC to describe just the southern part of the peninsula(e).<Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. This would push the custom of referring to Italy as a ‘continent’ back near to the time of Plato. More recently, Armin Wolf, the German historian, when writing about Scheria relates(f) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the ‘continente’.” This continuing usage is further confirmed by a current travel site(d) and by author, Robert Fox[1168.141]. I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and can be seen as offering the most rational explanation for the use of the word ‘continent’ in Timaeus 25a.

When you consider that close to Italy are located the large islands of Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, as well as smaller archipelagos such as the Egadi, Lipari and Maltese groups, the idea of Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean can be seen as highly compatible with Plato’s description.

If we accept that Plato stated unambiguously that the domain of Atlantis included at least part of southern Italy and also declared that Atlantis attacked from beyond the Pillars of Heracles, then this appellation could not be applied at that time to any location in the vicinity of the Strait of Gibraltar but must have been further east, probably not too far from Atlantean Italy. This matches earlier alternative locations recorded by classical writers who placed the ‘Pillars’ at the straits of Messina or Sicily. I personally favour Messina, unless there is stronger evidence that some of the islands in or near the Strait of Sicily such as the Maltese or Pelagian Islands or Pantelleria were home to the ‘Pillars’.

(a) http://www.richardcassaro.com/hidden-italy-the-forbidden-cyclopean-ruins-of-giants-from-atlantis

(b) Archive 2509P (Eng) Archive 2943 (Ital)

(c) Archive 2946

(d) Four Ways to Do Sicily – Articles – Departures (archive.org)

(e) https://profilbaru.com/article/Name_of_Italy *

(f) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(g) http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(h) http://2010-q-conference.com/ophir/ophir-27-10-09.pdf

Magna Graecia *

Magna Graecia is the term applied to those parts of southern Italy and  Sicily that were colonised by the Greeks, beginning as early as the 8th century BC. An interesting fact is that Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(b) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(d). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. This would push the custom of referring to Italy as a ‘continent’ back to the time of Plato. More recently, Armin Wolf (1935- ), the German historian, when writing about Scheria relates(a) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” This continuing usage is confirmed by a current travel site(c). I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and can be seen as offering a more rational explanation for the use of the word ‘continent’ in Timaeus 25a, adding to the idea of Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean.

Sicily that were colonised by the Greeks, beginning as early as the 8th century BC. An interesting fact is that Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(b) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(d). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. This would push the custom of referring to Italy as a ‘continent’ back to the time of Plato. More recently, Armin Wolf (1935- ), the German historian, when writing about Scheria relates(a) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” This continuing usage is confirmed by a current travel site(c). I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and can be seen as offering a more rational explanation for the use of the word ‘continent’ in Timaeus 25a, adding to the idea of Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean.

Giuseppe Palermo in his 2012 book Atlantide degli italiani is now bravely promoting the idea that Plato’s Atlantis was originally located beneath the town of Acri and the surrounding region of Calabria. He supports his claim by matching measurements provided by Plato with physical features around Acri(e). However surprising this idea may seem, it should be pointed out that according to Plato, Atlanteans had occupied southern Italy as far north as Tyrrhenia (Timaeus 25b & Critias 114c). If all this is not true, as a second prize, Acri can at least claim to be the birthplace of the famous American bodybuilder, Charles Atlas!

The Greeks began their gradual expansion westward between the 9th and 6th centuries BC, a development clearly illustrated on an excellent series of online maps(h). Understandably, they would have taken the shortest route from the Greek mainland to the heel of Italy and later on to Sicily. As they progressed with their colonisation new limits were set, and in time, exceeded. I suggest that these limits were each in turn designated the ‘Pillars of Heracles’ as they expanded. I speculate that Capo Colonna (Cape of the Column) in Calabria may have been one of those boundaries. Interestingly, 18th-century maps show up to five islands near the cape that are no longer visible(g), suggesting the possibility that in ancient times they could have been even more extensive, creating a strait that might have matched Plato’s description. On the other hand, the Strait of Messina was one of the locations recorded as the site of the ‘Pillars’ and considering that mariners at that time preferred to hug the coast, I would opt for the Strait of Messina rather than the more frequently proposed Strait of Sicily. A strait is defined as a narrow sea passage, a description that seems inappropriate for the 96 miles that separate Sicily from Tunisia.

For a brief history of the rise and fall of Magna Graecia, have a look at the classical wisdom website(f).

It is also noteworthy that there are a number of towns in Calabria where ancient Greek is still spoken(i). Similarly, back on the Peloponnese, the language of Sparta, Tsakonika, is still spoken by about 2,000 people in an area limited to 13 towns, villages and hamlets located around the village of Pera Melana(j).

(a) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(b) http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(c) Four Ways to Do Sicily – Articles – Departures (archive.org)

(d) https://profilbaru.com/article/Name_of_Italy *

(e) https://www.atlantid.info/?page_id=539

(f) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20180824200049/https://classicalwisdom.com/magna-graecia-greater-greece/

(g) https://www.academia.edu/1152285/Discovery_of_Ancient_Harbour_Structures_in_Calabria_Italy_and_Implications_for_the_Interpretation_of_Nearby_Sites

(h) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20141105204103/https://learningobjects.wesleyan.edu/greek_colonies/

(i) http://www.madeinsouthitalytoday.com/mysterios-places.php

(j) BBC – Travel – The last speakers of ancient Sparta

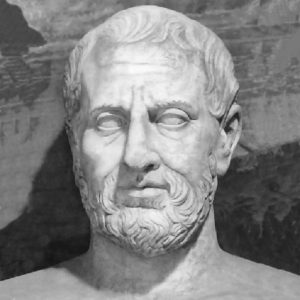

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (372–287 BC) was a student of Aristotle, whom he eventually succeeded at the Lyceum,  the home of the Peripatetic school of philosophy,*which he headed for thirty-six years. Eventually, he was succeeded by Strato of Lampsacus.*

the home of the Peripatetic school of philosophy,*which he headed for thirty-six years. Eventually, he was succeeded by Strato of Lampsacus.*

Theophrastus is frequently quoted as referring to Atlantis having colonies in the ‘sea’. Philo of Alexandria in his De Aeternitate Mindi[1423] has cited Theophrastus’ belief in the reality of Atlantis. Thorwald C. Franke expands on this in Appendix F of his Aristotle and Atlantis[880].

Theophrastus is sometimes referred to as the ‘father of botany’ and was one of the earliest writers to note that trees gained an extra outer layer each year. However, it would take over two thousand years before this fact led to the development of today’s invaluable science of dendrochronology.

Strait of Sicily

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

(i) Both the Strait of Messina to the north, between Sicily and Italy together with the Strait of Sicily to the south remained open.

(ii) The Strait of Messina was closed, joining Sicily to Italy, while the Strait of Sicily remained open.

(iii) Both the Strait of Messina and the Strait of Sicily were closed, providing a land bridge between Tunisia and Italy, separating the Eastern from the Western Mediterranean Basins.

I find it strange that what we call today the Strait of Sicily is 90 miles wide. Now the definition of ‘strait’ is a narrow passage of water connecting two large bodies of water. How 90 miles can be described as ‘narrow’ eludes me. Is it possible that we are dealing with a case of mistaken identity and that the ‘Strait of Sicily’ is in fact the Strait of Messina, which is narrow? Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(a) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(b).

Armin Wolf, the German historian, noted(e) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and was quite possibly referring to that same part of Italy which later became known as ‘Magna Graecia’. Robert Fox in The Inner Sea[1168.141] confirms that this long-standing usage of ‘continent’ refers to Italy.

It is worth pointing out that the Strait of Messina is sometimes referred to in ancient literature as the Pillars of Herakles and designates the sea west of this point as the ‘Atlantic Ocean’. Modern writers such as Sergio Frau and Eberhard Zangger, among others, have pointed out that the term ‘Pillars of Herakles’ was applied to more than one location in the Mediterranean in ancient times.

The Strait of Messina is frequently associated with the story of Scylla & Charybdis, which led Arthur R. Weir in a 1959 article(d) to refer to ancient documents, which state that Scylla & Charybdis lie between the Pillars of Heracles.

In 1910, the celebrated Maltese botanist, John Borg, proposed[1132] that Atlantis had been situated on what is now submerged land between Malta and North Africa. A number of other researchers, such as Axel Hausmann and Alberto Arecchi, have expressed similar ideas.

The Strait of Sicily is home to a number of sunken banks, previously exposed during the Last Ice Age. As levels rose most of these disappeared, an event observed by the inhabitants of the region at that time. The MapMistress website(c) has proposed that one of these banks was the legendary Erytheia, the sunken island of the far west. The ‘far west’ later became the Strait of Gibraltar but for the early Greeks it was the Central Mediterranean.

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(d) Atlantis – A New Theory, Science Fantasy #35, June 1959 pp 89-96 https://drive.google.com/file/d/10JTH401O_ew1fs8uhXR9C5IjNDvqnmft/view

>(e) Wayback Machine (archive.org) See Note 5<

Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina is, at its narrowest point, just 2 miles wide. A number of classical writers refer to a time when Sicily was still connected to Italy. In fact legend has it that Heracles was responsible for their separation. However, Cyprian Broodbank has pointed out in his monumental work, The Making of the Middle Sea, that “Today, the Messina strait dividing it (Sicily) from peninsular Italy is a minimum of 3 km (2 miles) wide and 72 metres (235 ft) in depth at its shallowest point. On the face of it, therefore, Sicily and mainland Italy should have fused under full glacial conditions. Yet this spot lies on a plate boundary and has already risen several metres over the last 150 years for which accurate measurements exist. Add a 127,000-71,000-year-old beach now elevated 90m (300ft) above the sea near the strait and we might start to wonder whether Sicily was ever solidly attached to the other land.”[1127.91] Nevertheless, he does suggest that early man possibly had stepping-stones in the form of islets and shallows between the two landmasses.

The Strait of Messina had a reputation in antiquity for having dangerous currents, which are thought to be the inspiration for Homer‘s sea monsters, Scylla and Charybdis. Heinrich Schliemann supported this identification[1243]. The currents there are still very dangerous, but nevertheless the strait is a busy waterway with both commercial and pleasure craft, indicating that the conditions there can be mastered. The hazards were situated at the northern end of the Strait, where today there is a town appropriately called Scilla on the Calabrian side.

The strait is sometimes offered as an earlier site for the Pillars of Heracles prior to the Western Mediterranean becoming more frequently navigated by the ancient Greeks, at which time the term was transferred to the Strait of Gibraltar. Winfried Huf is a keen supporter of ‘Pillars’ having been located at Messina. A constituent part of the Western Mediterranean was the Tyrrhenian Sea, which, for the Greeks, would have been most easily accessed through the Strait of Messina.

The earliest westward expansion of the Greeks was understandably to what became known as Magna Graecia in Sicily and southern Italy. The Phoenician expansion was along the north African coast eventually establishing Carthage at the Strait of Sicily. The ships available at that time were not designed for the open sea, but were usually kept within sight of land. I am inclined to think that the early Greeks would have had the Strait of Messina as the location of their Pillars of Heracles leading to the little known Western Mediterranean (or Tyrrhenian Sea), apparently referred to by some as the ‘Atlantic Sea’, whereas the Strait of Sicily might have led to conflict with the Phoenicians!

It is interesting that from around 330 BC and for nearly a thousand years(b) the Strait of Messina was known as Fretum Siculum, which translates as the Sicilian Strait. Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(c) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139).

>Alexander V. Podossinov in his paper on straits and their significance for the ancients commented “the Carthaginians for a long time did not permit the Greeks to pass through the Straits of Messina and had power over the whole western Mediterranean.”(d)<

Support for the idea of the Western Mediterranean being the ‘Sea of Atlantis’ with the ‘Pillars’ at the Strait of Messina is presented on a French forum(a), which offers the map below.

(a) https://histoiresecrete.leforum.eu/t716-quelques-questions-se-poser-sur-le-Tim-e-Critias.htm

(b) https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/462494

Continent *

The term ‘Continent’, is derived from the Latin terra continens, meaning ‘continuous land’ and in English is relatively new, not coming into use until the Middle English period (11th-16th centuries). Apart from that, it is sometimes used to imply the mainland. The Scottish island of Shetland is known by the smaller islands in the archipelago as Mainland, its old Norse name was Megenland, which means mainland. In turn, the people of Mainland, Shetland, will apply the same title to Britain, who in turn apply the term ‘continuous land’ or continent to mainland Europe. It seems that the term is relative.

The term has been applied arbitrarily by some commentators to Plato’s Atlantis, usually by those locating it in the Atlantic. Plato never called Atlantis a continent, but instead, as the sixteen instances below prove, he consistently referred to it as an island, probably the one containing the capital city of the confederation or alliance!

[Timaeus 24e, 25a, 25d Critias 108e, 113c, 113d, 113e, 114a, 114b, 114e, 115b, 115e, 116a, 117c, 118b, 119c]

Several commentators have assumed that when Plato referred to an ‘opposite continent’ he was referring to the Americas, however, Herodotus, who flourished after Solon and before Plato, was quite clear that there were only three continents known to the Greeks, Europe, Asia and Libya (4.42). In fact, before Herodotus, only two landmasses were considered continents, Europe and Asia, with Libya sometimes considered part of Asia. Furthermore, Anaximander drew a ‘map’ of the known world (left), a century after Herodotus, showing only the three continents, without any hint of territory beyond them.

Nevertheless, there has always been a school of thought that supported the idea of the ancient Greeks having knowledge of the Americas. In 1900, Peter de Roo in History of America before Columbus [890] not only supported this contention but suggested further that ancient travellers from America had travelled to Europe [Vol.1.Chap 5].

Daniela Dueck in her Geography in Classical Antiquity [1749] noted that “Hecataeus of Miletus divided his periodos gês into two books,each devoted to one continent, Europe and Asia, and appended his description of Egypt to the book on Asia. In his time (late sixth century bce), there was accordingly still no defined identity for the third continent. But in the fifth century the three continents were generally recognized, and it became common for geographical compositions in both prose and poetry to devote separate literary units to each continent.”

So when Plato does use the word ‘continent’ [Tim. 24e, 25a, Crit. 111a] we can reasonably conclude that he was referring to one of these landmasses, and more than likely to either Europe or Libya (North Africa) as Atlantis was in the west, ruling out Asia.

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(b) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). It would seem that in this particular circumstance the term ‘Sicilian Strait’ refers to the Strait of Messina, which is another example of how ancient geographical terms often changed their meaning over time (see Atlantic & Pillars of Herakles).

The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(d). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. This would push the custom of referring to Italy as a ‘continent’ back to the time of Plato, who clearly states (Tim. 25a) that the Atlantean alliance “ruled over all the island, over many other islands as well. and over sections of the continent.” (Wells). The next passage recounts their control of territory in Europe and North Africa, so it naturally begs the question as to what was ‘the continent’ referred to previously? I suggest that the context had a specific meaning, which, in the absence of any other candidate and the persistent usage over the following two millennia can be reasonably assumed to have been southern Italy.

Centuries later, the historian, Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) refers at least twice[1523.6.209/10] to the ‘continent of Italy’. More recently, Armin Wolf (1935- ), the German historian, when writing about Scheria relates(a) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” This continuing usage of the term is confirmed by a current travel site(c) and by author, Robert Fox in The Inner Sea [1168.141].

I suggest that Plato similarly used the term and can be seen as offering a more rational explanation for the use of the word ‘continent’ in Timaeus 25a, adding to the idea of Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean.

Giovanni Ugas claims that the Mediterranean coast of southern Spain and France, along with the Italian peninsula constituted the ‘true continent’ (continente vero) referred to by Plato. (see below)

Furthermore, the text informs us that this opposite continent surrounds or encompasses the true ocean, a description that could not be applied to either of the Americas as neither encompasses the Atlantic, which makes any theory of an American Atlantis more than questionable.

Modern geology has definitively demonstrated that no continental mass lies in the Atlantic and quite clearly the Mediterranean does not have room for a sunken continent.

(a) Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(b) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(c) Four Ways to Do Sicily – Articles – Departures (archive.org)

(e) The Elusive Location of Atlantis Part 1 – Luciana Cavallaro (archive.org) *

Classical Writers Supporting the Existence of Atlantis

Classical Writers Supporting the Existence of Atlantis

Although many of the early writers are quoted as referring to Plato’s Atlantis or at least alluding to places or events that could be related to his story there is no writer who can be identified as providing unambiguous independent evidence for Atlantis’ existence. One explanation could be that Atlantis may have been known by different names to different peoples in different ages, just as the Roman city of Aquisgranum was later known as Aachen to the Germans and concurrently as Aix-la-Chapelle to the French. However, it would have been quite different if the majority of post-Platonic writers had completely ignored or hotly disputed the veracity of Plato’s tale.

Sprague de Camp, a devout Atlantis sceptic, included 35 pages of references to Atlantis by classical writers in Appendix A to his Lost Continents.[194.288]

Alan Cameron, another Atlantis sceptic, is adamant that ”it is only in modern times that people have taken the Atlantis story seriously, no one did so in antiquity.” Both statements are clearly wrong, as can be seen from the list below and my Chronology of Atlantis Theories and even more comprehensively by Thorwald C. Franke’s Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis (Critical history of the hypotheses on Plato’s Atlantis)[1255].

H.S. Bellamy mentions that about 100 Atlantis references are to be found in post-Platonic classical literature. He also argues that if Plato “had put forward a merely invented story in the Timaeus and Critias Dialogues the reaction of his contemporaries and immediate followers would have been rather more critical.” Thorwald C. Franke echoes this in his Aristotle and Atlantis[880.46]. Bellamy also notes that Sais, where the story originated, was in some ways a Greek city having regular contacts with Athens and should therefore have generated some denial from the priests if the Atlantis tale had been untrue.

Homer(c.8thcent. BC)wrote in his famous Odyssey of a Phoenician island called Scheria that many writers have controversially identified as Atlantis. It could be argued that this is another example of different names being applied to the same location.

Hesiod (c.700 BC) wrote in his Theogonyof the Hesperides located in the west. Some researchers have identified the Hesperides as Atlantis.

Herodotus (c.484-420 BC)regarded by some as the greatest historian of the ancients, wrote about the mysterious island civilization in the Atlantic.

Hellanicus of Lesbos (5th cent. BC) refers to ‘Atlantias’. Timothy Ganz highlights[0376] one line in the few fragments we have from Hellanicus as being particularly noteworthy, “Poseidon mated with Celaeno, and their son Lycus was settled by his father in the Isles of the Blest and made immortal.”

Thucydides (c.460-400 BC)refers to the dominance of the Minoan empire in the Aegean.

Syrianus (died c.437 BC) the Neoplatonist and one-time head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, considered Atlantis to be a historical fact. He wrote a commentary on Timaeus, now lost, but his views are recorded by Proclus.

Eumelos of Cyrene (c.400 BC) was a historian and contemporary of Plato who placed Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean between Libya and Sicily.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Plato’s pupil is constantly quoted in connection with his alleged criticism of Plato’s story. This claim was not made until 1819 when Delambre misinterpreted a commentary on Strabo by Isaac Casaubon. This error has been totally refuted by Thorwald C. Franke[880]. Furthermore, it was Aristotle who stated that the Phoenicians knew of a large island in the Atlantic known as ’Antilia’. Crantor (4th-3rdcent. BC) was Plato’s first editor, who reported visiting Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis. However, Jason Colavito has pointed out that according to Proclus, Crantor was only told by the Egyptian priests that the carved pillars were still in existence.

Crantor (4th-3rd cent. BC) was Plato’s first editor, who reportedly visited Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis. However, Jason Colavito has pointed out(a) that according to Proclus, Crantor was only told by the Egyptian priests that the carved pillars were still in existence.

Theophrastus of Lesbos (370-287 BC) refers to colonies of Atlantis in the sea.

Theopompos of Chios (born c.380 BC), a Greek historian – wrote of the huge size of Atlantis and its cities of Machimum and Eusebius and a golden age free from disease and manual labour. Zhirov states[458.38/9] that Theopompos was considered a fabulist.

Apollodorus of Athens (fl. 140 BC) who was a pupil of Aristarchus of Samothrace (217-145 BC) wrote “Poseidon was very wrathful, and flooded the Thraisian plain, and submerged Attica under sea-water.” Bibliotheca, (III, 14, 1.)

Poseidonius (135-51 BC.) was Cicero’s teacher and wrote, “There were legends that beyond the Hercules Stones there was a huge area which was called “Poseidonis” or “Atlanta”

Diodorus Siculus (1stcent. BC), the Sicilian writer who has made a number of references to Atlantis.

Marcellus (c.100 BC) in his Ethiopic History quoted by Proclus [Zhirov p.40] refers to Atlantis as consisting of seven large and three smaller islands.

Statius Sebosus (c. 50 BC), the Roman geographer, tells us that it was forty days’ sail from the Gorgades (the Cape Verdes) and the Hesperides (the Islands of the Ladies of the West, unquestionably the Caribbean – see Gateway to Atlantis).

Timagenus (c.55 BC), a Greek historian wrote of the war between Atlantis and Europe and noted that some of the ancient tribes in France claimed it as their original home. There is some dispute about the French druids’ claim.

Philo of Alexandria (b.15 BC) also known as Philo Judaeus also accepted the reality of Atlantis’ existence.

Strabo (67 BC-23 AD) in his Geographia stated that he fully agreed with Plato’s assertion that Atlantis was fact rather than fiction.

Plutarch (46-119 AD) wrote about the lost continent in his book Lives, he recorded that both the Phoenicians and the Greeks had visited this island which lay on the west end of the Atlantic.

Pliny the Younger (61-113 AD) is quoted by Frank Joseph as recording the existence of numerous sandbanks outside the Pillars of Hercules as late as 100 AD.

Tertullian (160-220 AD) associated the inundation of Atlantis with Noah’s flood.

Claudius Aelian (170-235 AD) referred to Atlantis in his work The Nature of Animals.

Arnobius (4thcent. AD.), a Christian bishop, is frequently quoted as accepting the reality of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395 AD) [see Marcellinus entry]

Proclus Lycaeus (410-485 AD), a representative of the Neo-Platonic philosophy, recorded that there were several islands west of Europe. The inhabitants of these islands, he proceeds, remember a huge island that they all came from and which had been swallowed up by the sea. He also writes that the Greek philosopher Crantor saw the pillar with the hieroglyphic inscriptions, which told the story of Atlantis.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (6thcent. AD), a Byzantine geographer, in his Topographica Christiana (547 AD) quotes the Greek Historian, Timaeus (345-250 BC) who wrote of the ten kings of Chaldea [Zhirov p.40]. Marjorie Braymer[198.30] wrote that Cosmas was the first to use Plato’s Atlantis to support the veracity of the Bible.

There was little discussion of Atlantis after the 6th century until the Latin translation of Plato’s work by Marsilio Ficino was produced in the 15th century.

(a) https://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/the-first-believer-why-early-atlantis-testimony-is-suspect

Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) also known as Philo the Jew, was a philosopher based in Alexandria. He was a firm supporter of the reality of Atlantis’ existence. He wrote on the subject in his De Aeternitate Mundi (On the Eternity of the Earth) [1423.v.141]+ where he is thought by some to be quoting Theophrastus(a), Aristotle’s successor. This view is held by Thorwald C. Franke [0880.131] and J. V. Luce in Atlantis: Fact or Fiction [0522.51].

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) also known as Philo the Jew, was a philosopher based in Alexandria. He was a firm supporter of the reality of Atlantis’ existence. He wrote on the subject in his De Aeternitate Mundi (On the Eternity of the Earth) [1423.v.141]+ where he is thought by some to be quoting Theophrastus(a), Aristotle’s successor. This view is held by Thorwald C. Franke [0880.131] and J. V. Luce in Atlantis: Fact or Fiction [0522.51].

It is interesting that from around 330 BC and for nearly a thousand years(b) the Strait of Messina was known as Fretum Siculum, which translates as the Sicilian Strait, prompting Philo to write “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” [v.139].

Note how Philo refers to Italy as a continent.

[1423.v.141]+ https://archive.org/details/deaeternitatemu00philgoog *