Alberto Arecchi

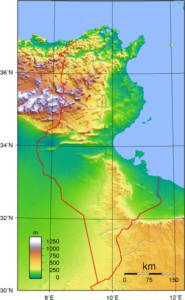

Central Mediterranean

The Central Mediterranean is a very geologically unstable region containing as it does all of Europe’s land-based active volcanoes(a), regular seismic(b) activity with the attendant risk of tsunamis. It is now estimated that a devastating tsunami will hit the Mediterranean every 100 years(c). While the Aegean region experiences the greatest number of earthquakes, the Central Mediterranean, particularly around Sicily is also prone to regular tremors.

The idea that Atlantis was situated in this region is advocated by a number of researchers, including Alberto Arecchi, Férréol Butavand, Anton Mifsud, Axel Hausmann, as well as this compiler. Plato unambiguously referred to only two places as Atlantean territory (Crit.114c & Tim 25b) North Africa and Southern Italy as far as Tyrrhenia (Tuscany) plus a number of unspecified islands.

The area between Southern Italy and Tunisia has had a great number of sites proposed for the Pillars of Herakles, while possible locations for Gades are on offer with a number places still known today by cognates of that name.

Plato clearly includes continental territory as part of the Atlantean domain as well as a number of important islands. Within a relatively small geographical area, you have two continents, Africa and Europe represented by Tunisia and Italy respectively, as well as the islands of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and Malta together with a number of smaller archipelagos, matching Plato’s description exactly. The later Carthaginian Empire also occupied much of the same territory apart from eastern Sicily and southern Italy which by then was controlled by the Greeks and known as Magna Graecia.

For me, the clincher is that within that region we have the only place in the entire Mediterranean to have been home to elephants up to Roman times – Northwest Africa.

(a) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volcanology_of_Italy

(b) The Europeam Mediterranean Seismic Centre – EMSC, records all activity in the region.

(c) Tsunami Alarm System – A3M Tsunami Alarm System (tsunami-alarm-system.com) (German & English)

Bradford, Ernle

Ernle Bradford (1922-1986) served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, after which he settled in Malta. He then undertook the task of retracing the route taken by Ulysses starting from Troy and recounted in his book, Ulysses Found[1011].

Ernle Bradford (1922-1986) served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, after which he settled in Malta. He then undertook the task of retracing the route taken by Ulysses starting from Troy and recounted in his book, Ulysses Found[1011].

He made only one passing reference to Atlantis (p.57) which may be of interest to supporters of a Central Mediterranean Atlantis. When discussing the Egadi Islands off the west coast of Sicily he describes Levanzo, the smallest of the group as being “once joined to Sicily, and the island was surrounded by a large fertile plain. Levanzo, in fact, was joined to more than Sicily. Between this western corner of the Sicilian coast and the Cape Bon peninsula in Tunisia there once lay rich and fertile valleys-perhaps, who knows, long lost Atlantis?”*This would seem to be close the views of Alberto Arecchi and others.*

Kerkenna

Kerkennah is the name of a group of Tunisian islands situated off its east coast.*The archipelago is one of the locations claimed to include Homer’s ‘Island of Goats’ and the home of the Cyclops in the Odyssey.*

Kerkennah is the name of a group of Tunisian islands situated off its east coast.*The archipelago is one of the locations claimed to include Homer’s ‘Island of Goats’ and the home of the Cyclops in the Odyssey.*

In a recent book[980] by Antonio Usai he claims that the original Pillars of Hercules were situated between the islands and the mainland. In support of his contention he quotes fron The Voyageof Hanno and other classical writers.

Férréol Butavand thought that Atlantis had existed in the Central Mediterranean and had included the Kerkennah Islands. Alberto Arecchi has expressed similar views.

Syrtis

Syrtis was the name given by the Romans to two gulfs off the North African coast; Syrtis Major which is now known as the Gulf of Sidra off Libya and Syrtis Minor, known today as the Gulf of Gabes in Tunisian waters. They are both shallow sandy gulfs that have been feared from ancient times by mariners. In the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 27.13-18) it is described how St. Paul on his way to Rome was blown off course and feared that they would run aground on ‘Syrtis sands.’

However, they were shipwrecked on Malta or as some claim on Mljet in the Adriatic.

The earliest modern reference to these gulfs that I can find in connection with Atlantis was by Nicolas Fréret in the 18th century when he proposed that Atlantis may have been situated in Syrtis Major. Giorgio Grongnet de Vasse expressed a similar view around the same time. Since then there has been little support for the idea until recent times when Winfried Huf designated Syrtis Major as one of his five divisions of the Atlantean Empire.

However, the region around the Gulf of Gabes has been more persistently associated with aspects of the Atlantis story. Inland from Gabes are the chotts, which were at one time connected to the Mediterranean and considered to have been part of the legendary Lake Tritonis, sometimes suggested as the actual location of Atlantis.

In the Gulf itself, Apollonius of Rhodes placed the Pillars of Herakles(a) , while Anton Mifsud has drawn attention[0209] to the writings of the Greek author, Palefatus of Paros, who stated (c. 32) that the Columns of Heracles were located close to the island of Kerkennah at the western end of Syrtis Minor. Lucanus, the Latin poet, located the Strait of Heracles in Syrtis Minor. Mifsud has pointed out that this reference has been omitted from modern translations of Lucanus’ work!

Férréol Butavand was one of the first modern commentators to locate Atlantis in the Gulf of Gabés[0205]. In 1929 Dr. Paul Borchardt, the German geographer, claimed to have located Atlantis between the chotts and the Gulf, while more recently Alberto Arecchi placed Atlantis in the Gulf when sea levels were lower(b) . George Sarantitis places the ‘Pillars’ near Gabes and Atlantis itself inland, further west in Mauritania, south of the Atlas Mountains. Antonio Usai also places the ‘Pillars’ in the Gulf of Gabes.

In 2018, Charles A. Rogers published a paper(c) on the academia.edu website in which he identified Tunisia as Atlantis with it capital located at the mouth of the Triton River on the Gulf of Gabes. He favours Plato’s 9.000 ‘years’ to have been lunar cycles, bringing the destruction of Atlantis into the middle of the second millennium BC and coinciding with the eruption of Thera which created a tsunami that ran across the Mediterranean destroying the city with the run-up and its subsequent backwash. This partly agrees with my conclusions in Joining the Dots!

Also See: Gulf of Gabes and Tunisia

(a) Argonautica Book IV ii 1230

(c) https://www.academia.edu/36855091/Atlantis_Once_Lost_Now_Found?auto=download*

Verne, Jules Gabriel

Jules Gabriel Verne (1828-1905) was a French novelist credited with ‘inventing’ science fiction. It is claimed that his 1870 classic, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, in which the lost city of Atlantis is featured, is said to have inspired Ignatius Donnelly to undertake his researches that led to the publication, in 1882, of his own foundational work, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. It is also suggested that Donnelly’s second catastrophist work, Ragnarok, was also prompted by another of Verne’s novels – Off on a Comet.

The last book published before his death was L’Invasion de la Mer, only recently translated into English as Invasion of the Sea[779]. It was based on an actual suggestion by a French geographer that the chotts of Algeria and Tunisia should be reconnected with the Mediterranean at the Gulf of Gabes. These chotts or salt lakes are reputed to have been the location of the legendary Lake Tritonis and considered by some to have included the port of Atlantis. Alberto Arecchi has proposed that Lake Tritonis was the original ‘Atlantic Sea’.

>In 1863, Verne wrote Paris in the 20th Century which was not published until 1994 (in French), because his publisher thought it too farfetched and might damage his reputation. It was eventually published in English in 1997 [2067]. In this science fiction novel, he offers an astonishing number of technological predictions, such as motor cars, fax machines, computers, electronic music, etc, etc, etc(a).<

Tunisia

Tunisia has now offered evidence of human activity dated to nearly 100,000 years ago(d) at a site near Tozeur, in the southwest of the country, where the Chotts are today.

Alfred Merlin (1876-1965) was head of the Tunisian Antiquities Administration from 1905 to 1920. In 1907 the discovery of ancient artefacts of the old Tunisian port of Mahdia was initially thought by Merlin to be relics from Atlantis. However, following some investigation, the matter seemed to fade from Merlin’s field of interest and apparently never wrote anything on the subject(n).

Tunisia was proposed in the 1920s, by Albert Herrmann, as holding the location of Plato’s Atlantis, at a dried-up saltwater lake known today as Chott el Djerid and was, according to Herrmann, previously called Lake Tritonis.

>>Léonce Joleaud was a French Professor of Geology and Palaeontology. In 1928 he became president of the Geological Society of France(o) and in the same year, he published a paper entitled L’Atlantide envisagée par un Paléontologiste (Atlantis considered by a Paleontologist). He was satisfied that Plato’s island had been located in Southern Tunisia, as did many of his compatriots at that time.<<

Around this same period Dr. Paul Borchardt, a German geologist, also favoured a site near the Gulf of Gabés, off Tunisia, as the location of Atlantis. He informed us that Shott el Jerid had also been known locally as Bahr Atala or Sea of Atlas.

geologist, also favoured a site near the Gulf of Gabés, off Tunisia, as the location of Atlantis. He informed us that Shott el Jerid had also been known locally as Bahr Atala or Sea of Atlas.

Hong-Quan Zhang has a Ph.D. in Fluid Mechanics and lectures at Tulsa University. He is a recent supporter of Atlantis being located in the chotts of Tunisia and Algeria(l). He offers his interpretation of excerpts from the ancient Pyramid Texts in support of his contention(m).

More recently, Alberto Arecchi developed a theory that places Atlantis off the present Tunisian coast with a large inland sea, today’s Chotts, which he identifies as the original ‘Atlantic Sea’, straddling what is now the Tunisian-Algerian border. Arecchi claims that this was nearly entirely emptied into the Mediterranean as a result of seismic or tectonic activity in the distant past.

In 2018, Charles A. Rogers published a paper(f) on the academia.edu website in which he identified Tunisia as Atlantis with its capital located at the mouth of the Triton River on the Gulf of Gabes. He favours Plato’s 9.000 ‘years’ to have been lunar cycles, bringing the destruction of Atlantis into the middle of the second millennium BC and coinciding with the eruption of Thera which created a tsunami that ran across the Mediterranean destroying the city with the run-up and its subsequent backwash. This partly agrees with my conclusions in Joining the Dots!

There is clear evidence(b) that Tunisia had been home to the last wild elephants in the Mediterranean region until the demise of the Roman Empire. Furthermore, North Africa and Tunisia in particular have been considered the breadbasket of imperial Rome supplying much of its wheat and olive oil. In particular the Majardah (Medjerda) River valley has remained to this day the richest grain-producing region of Tunisia(i). Roman Carthage became the second city of the Western Empire. Although the climate has deteriorated somewhat since then, it is still possible to produce two crops a year in the low-lying irrigated plains of Tunisia. Furthermore, around the mountains of northwest Africa, there is an abundance of trees including Aleppo pine forests that cover over 10,000 km2 (h). All these details echo Plato’s description of Atlantis and justify the consideration of Tunisia as being at least part of the Atlantean confederation.

It is worth noting that Mago, was the Carthaginian author of a 28-volume work on the agricultural practices of North Africa. After the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, his books were brought to Rome, where they were translated from Punic into Latin and Greek and were widely quoted thereafter. Unfortunately, the original texts did not survive, so today we only have a few fragments quoted by later writers. Clearly, Mago’s work was a reflection of a highly developed agricultural society in that region, a description that could also be applied to Plato’s Atlantis!

In 2017, the sunken city of Neapolis was located off the coast of Nabeul, southeast of Tunis. This city was reportedly submerged by a tsunami ”on July 21 in 365 AD that badly damaged Alexandria in Egypt and the Greek island of Crete, as recorded by historian Ammianus Marcellinus.(e)(g)” However, water from a tsunami eventually drains back into the sea, but the demise of Neapolis might be better explained by liquefaction, in the same way, that Herakleion(j), near Alexandria, was destroyed, possibly by the same event. Neapolis and Herakleion are around 1,900 km apart, which suggests an astounding seismic event if both were destroyed at the same time!(e)

In addition to all that, in winter the northern coast of Tunisia is assailed with cold winds from the north bringing snow to the Kroumirie Mountains in the northwest(c).

Interestingly, in summer 2014, a completely new lake was discovered at Gafsa, just north of Shott el Jerid and quickly became a tourist attraction(a), but its existence was rather short-lived.

In November 2021, Aleksa Vu?kovi? published an article on the Ancient Origins website reviewing the current evidence for a Tunisian location for Plato’s Atlantis. Unfortunately, nothing new is offered that you cannot find here(k)!

To be clear, I consider parts of Tunisia to have been an important element in the Atlantean alliance, which according to Plato, also included southern Italy along with some of the Mediterranean islands (Tim.25a-b).

(a) https://www.unexplained-mysteries.com/news/270241/mysterious-lake-appears-in-tunisian-desert

(b) New Scientist. 7 February, 1985

(c) Tunisia Weather & Climate with Ulysses (archive.org)

(d) https://phys.org/news/2016-09-tunisian-year-human-presence.html

(f) https://www.academia.edu/36855091/Atlantis_Once_Lost_Now_Found

(g) Submerged Ancient Roman City Of Neapolis Discovered In Tunisia (archive.org)

(h) Northern Africa: Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia | Ecoregions | WWF (archive.org)

(i) https://www.britannica.com/place/Majardah-valley

(j) Science Notes 2001: The Sunken Cities of Egypt (ucsc.edu)

(l) https://medcraveonline.com/IJH/is-atlantis-related-to-the-green-sahara.html

(m) https://medcraveonline.com/IJH/IJH-06-00301.pdf

(n) Alfred Merlin – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

Lake Tritonis *

Lake Tritonis is frequently referred to by the classical writers. Ian Wilson refers to Scylax of Caryanda as having “specifically described Lake Tritonis extending in his time over an area of 2,300 km2.“ He also cites Herodotus as confirming it as still partly extant in his time, a century later, describing it as a ‘great lagoon’, with a ‘large river’ (the Triton) flowing into it.[185.185]

Lake Tritonis was considered the birthplace of Athene, the Greek Goddess of Wisdom, after whom Athens is named. The exact location of the lake is disputed but there is some consensus that the salty marshes or chotts of central Tunisia and North-East Algeria are the most likely candidates. It appears that these marshes originally formed a large inland sea connected to the Mediterranean but due to seismic activity in the area were cut off from the sea. Diodorus Siculus records this event in his third book.

I should also mention that Lake Tritonis along with the Greek island of Lemnos and the river Thermodon in northern Turkey, now known as Terme Çay, have all been associated with the Amazons(d).

Edward Herbert Bunbury, a former British MP, included a chapter(a) on Lake Tritonis in his 1879 book on the history of ancient geography [1531.v1.316]+.

geography [1531.v1.316]+.

In 1883, Edward Dumergue published[659]+ a brief study of the Tunisian chotts, which he concluded were the remnants of an ancient inland sea that had been connected to the Mediterranean Sea at the Gulf of Gabes.

Lucile Taylor Hansen in The Ancient Atlantic[572], has included a speculative map taken from Reader’s Digest showing Lake Tritonis, around 11.000 BC, as a megalake covering much of today’s Sahara, with the Ahaggar Mountains turned into an island. Atlantis is shown to the west in the Atlantic.

In 1967 Egerton Sykes published a paper entitled The Sahara Inland Sea in which he describes a vast inland sea of ‘remarkable proportions’ and “is attested not only by classical references but also by the fact that beneath most of it lies a layer of brackish water ranging from 200 to 500 feet below the ground. The various oases are believed to be located on patches where the depth is only about 50 feet, conducive to plant survival. The climatic change seems to have happened quite recently, around 5000 BC. B.C., since the classics contain numerous references to its [the inland sea] existence.”(e)

I should mention here that the Atlantis theory of George Sarantitis is entirely dependent on extensive inland waterways including the chotts of Tunisia and Algeria as well as a number of other large lakes and rivers in what is now the Sahara.

In modern times, Alberto Arecchi has taken the idea further[079] and suggested that the inland sea, where the chotts are now, was the original ‘Atlantic Sea’ and that the city of Atlantis was situated on an extended landmass to the east of Tunisia and connected to Sicily due to a lower sea level. Arecchi’s identification of the chotts with Lake Tritonis has now been adopted by Lu Paradise in a May 2015 blog(c). The Qattara Depression of Northern Egypt also contains a series of salt lakes and marshes and is believed by others to have been Lake Tritonis.

Cindy Clendenon is the author of a book [801.397] on hydromythology in which she concludes that “the now-extinct Lake Tritonis once was a Cyrenaican lagoon-sabkha complex near today’s Sabkha Ghuzayyil and Marsa Brega, Libya”(b), not in Tunisia! Clyde Winters also placed Lake Tritonis in Libya(f).

[659]+ https://archive.org/details/chottstunisorgr01dumegoog

[1531.v1.316]+ https://archive.org/stream/historyofancient01bunb#page/n6/mode/1up/search/Tritonis Vol.1

(a) Lake Tritonis – Jason and the Argonauts (archive.org) *

(b) https://www.abebooks.com/9780981842103/Hydromythology-Ancient-Greek-World-Earth-0981842100/plp

(d) https://www.myrine.at/Amazons/mobilIndex.html

(e) The Saharan Inland Sea – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(f) https://africanbloodsiblings.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/fertile-african-crescent-by-clyde-winters/

Tehenu and Temehu

Tehenu and Temehu are terms used in the ancient inscriptions of Egypt when referring to the Libyans. Ulrich Hofmann links them with the predecessors of the Berbers whom he identifies as the people of Atlantis in his recent book, Platons Insel Atlantis[161] published in German. Similar views are held by Alberto Arecchi.

Robert Temple discusses[736.414] the etymology of ‘ Ta Tehenu’ which although used to refer to Libya actually means ‘olive land’.

There is a website(a) which gives an overview of the land of the Temehu from 55 million BC until modern times. In 1983 UNESCO commissioned A.H.S. El-Mosallamy to write a paper on the relationship between the Tehenu and ancient Egypt(b).

*The Libyans controlled North Africa as far as the borders of Egypt and were constantly in conflict with the Egyptians. Plato describes the Atlantean control in North Africa in similar terms, which also fits with the Libyans (Labu) as one of the allies of the Sea Peoples .*

(a) https://www.temehu.com/History-of-Libya.htm

(b) https://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0005/000577/057711eb.pdf

Strait of Sicily

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

The Strait of Sicily is the name given to the extensive stretch of water between Sicily and Tunisia. Depending on the degree to which glaciation lowered the world’s sea levels during the last Ice Age; three views have emerged relating its possible effect on Sicily during that period:

(i) Both the Strait of Messina to the north, between Sicily and Italy together with the Strait of Sicily to the south remained open.

(ii) The Strait of Messina was closed, joining Sicily to Italy, while the Strait of Sicily remained open.

(iii) Both the Strait of Messina and the Strait of Sicily were closed, providing a land bridge between Tunisia and Italy, separating the Eastern from the Western Mediterranean Basins.

I find it strange that what we call today the Strait of Sicily is 90 miles wide. Now the definition of ‘strait’ is a narrow passage of water connecting two large bodies of water. How 90 miles can be described as ‘narrow’ eludes me. Is it possible that we are dealing with a case of mistaken identity and that the ‘Strait of Sicily’ is in fact the Strait of Messina, which is narrow? Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(a) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” (v.139). Some commentators think that Philo was quoting Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor. The name ‘Italy’ was normally used in ancient times to describe the southern part of the peninsula(b).

Armin Wolf, the German historian, noted(e) that “Even today, when people from Sicily go to Calabria (southern Italy) they say they are going to the “continente.” I suggest that Plato used the term in a similar fashion and was quite possibly referring to that same part of Italy which later became known as ‘Magna Graecia’. Robert Fox in The Inner Sea[1168.141] confirms that this long-standing usage of ‘continent’ refers to Italy.

It is worth pointing out that the Strait of Messina is sometimes referred to in ancient literature as the Pillars of Herakles and designates the sea west of this point as the ‘Atlantic Ocean’. Modern writers such as Sergio Frau and Eberhard Zangger, among others, have pointed out that the term ‘Pillars of Herakles’ was applied to more than one location in the Mediterranean in ancient times.

The Strait of Messina is frequently associated with the story of Scylla & Charybdis, which led Arthur R. Weir in a 1959 article(d) to refer to ancient documents, which state that Scylla & Charybdis lie between the Pillars of Heracles.

In 1910, the celebrated Maltese botanist, John Borg, proposed[1132] that Atlantis had been situated on what is now submerged land between Malta and North Africa. A number of other researchers, such as Axel Hausmann and Alberto Arecchi, have expressed similar ideas.

The Strait of Sicily is home to a number of sunken banks, previously exposed during the Last Ice Age. As levels rose most of these disappeared, an event observed by the inhabitants of the region at that time. The MapMistress website(c) has proposed that one of these banks was the legendary Erytheia, the sunken island of the far west. The ‘far west’ later became the Strait of Gibraltar but for the early Greeks it was the Central Mediterranean.

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html

(d) Atlantis – A New Theory, Science Fantasy #35, June 1959 pp 89-96 https://drive.google.com/file/d/10JTH401O_ew1fs8uhXR9C5IjNDvqnmft/view

>(e) Wayback Machine (archive.org) See Note 5<

Sicily

Sicily was known in earlier times as Trinacria because of its triangular shape. The island was first inhabited by modern humans during the last Ice Age(h) when lower sea levels exposed a land bridge between it and what is now mainland Italy.

>Antoine Gigal, the French writer and explorer noted(f) that “In the Odyssey, Homer refers to Sicily as Sikania (in classical texts it is also called Sikelia) and mentions the Sicanian Mountains. This is why one of the three native peoples of Sicily was named the Sicani (Sikanoi or Sicanians). They were probably there from 3000-1600 BC, from the earlier proto-Sican period, where various Mediterranean influences reached the Neolithic population that was based more in the central and western part of the island.”

She added later “Some modern researchers think that Siculo and his people originated from even further away, from the east. Prof. Enrico Caltagirone and Prof. Alfredo Rizza have even calculated that in the modern Sicilian language there are more than 200 words that come directly from Sanskrit. Then from the Bronze Age and classical antiquity there is evidence of another Sicilian people, the Elymians, who migrated from Anatolia and may have been descended from the famous “Sea Peoples”. The west of Anatolia was then occupied by non Indo-Europeans. Thucydides said they were refugees from Troy.

Indeed a group of Trojans are supposed to have survived the defeat of Troy, having escaped by sea, and settled in Sicily and mixed with the Sicani. Virgil even writes that they were led by the hero Acestes, king of Segesta in Sicily, who gave help to Priam and Aeneas, and had Anchises buried in Erix (modern Erice).”<

Plato was quite familiar with Sicily having paid a number of visits there(i) and on one occasion was sold as a slave having offended King Dionysius with his criticism of tyrannical rulers. Many think that his time in the capital, Syracuse, inspired elements of his description of the capital of Atlantis!

The island was probably first suggested as having a link with Atlantis by Mário Saa in a 1936 book in which he has Atlantis stretching from and including Sicily and the Maltese archipelago all the way to Tunisia. It was then more than four decades before Phyllis Young Forsyth wrote her book, Atlantis: The Making of Myth [266], in which she expressed her belief that Plato wrote the Atlantis story as an anti-war allegory partly based on his own experiences with the king of Syracuse.

More recently a number of other  writers have also put Sicily forward as a location for Atlantis. One of these was Francesco Costarella, who is an Italian researcher and the author of two books relating to Atlantis. The first [1636] puts forward the idea that Plato’s Atlantis and the biblical Deluge, are in the author’s words, ‘two sides of the same coin’, while in the second [1637], he identifies Sicily as the location of Atlantis.

writers have also put Sicily forward as a location for Atlantis. One of these was Francesco Costarella, who is an Italian researcher and the author of two books relating to Atlantis. The first [1636] puts forward the idea that Plato’s Atlantis and the biblical Deluge, are in the author’s words, ‘two sides of the same coin’, while in the second [1637], he identifies Sicily as the location of Atlantis.

In the main, it has been European investigators who have advocated such a Sicilian connection and some have gone further and proposed a land bridge with Tunisia within the memory of man.

Dr Peter Jakubowski also offers(a) Sicily and the Malta Plateau as the location of Atlantis. He proposes a cosmic impact in the Atlantic which closed the Strait of Gibraltar around 4800 BC. When the dam eventually broke, the Mediterranean to the west of Sicily began to fill. This was then followed by the breaching of the land bridge between Sicily and Africa and finally, the dam in the Bosporus broke, flooding what was a much smaller Black Sea than we have today. Jakubowski’s site is apparently a reworking of Axel Hausmann’s book. A few years ago he revamped his website but removed all the Atlantis material.

Patrick Archer has also adopted the concept of a Sicilian land bridge and promotes the idea that the breaching of it and its consequences were the inspiration for the biblical Deluge(e).

Zhirov noted that “the Mediterranean is fairly shallow between Sicily and Tunisia. There are vast sandbanks and shoals. It may be considered as beyond all doubt that this region subsided recently and that there was a broad isthmus between Sicily and Tunisia.”

Alberto Arecchi(b) has added his voice in support of this Sicilian land bridge linking Italy with Africa and places Atlantis off the coast of modern Tunisia.

Further support has come from Thomas J. Krupa in his 2014 book[1010], which proposes that the land bridge was composed of limestone which over time had been partially dissolved by rainwater and was under stress from the rising sea levels on its western side. He considers the land bridge the most likely location for Atlantis, which was destroyed when the isthmus was sundered by an earthquake.

Another exponent of a relatively recent collapse of the Gibraltar Dam is the previously mentioned Axel Hausmann[371] who locates Atlantis between Sicily and Malta.

Alfred E. Schmeck has written[542], in German, a detailed look at Sicily as the inspiration for Plato’s narrative.

Thorwald C. Franke has a well-balanced website(c), in German and English, supporting the idea of a Bronze Age Sicilian Atlantis. For topographical reasons, he places the city on the Plains of Catania on the east coast of the island. He sees that the importance of Atlantis within his hypothesis “is the transfer of culture from the eastern to the Western Mediterranean, e.g. there can be found parallels between the culture of the Etruscans, whose role in bringing eastern culture to the west is widely acknowledged.”

Sicily is also home to a number of step pyramids similar to the Canarian examples(d). Antoine Gigal offers(f) an extensively illustrated article about 23 previously unrecorded Sicilian pyramids as well as seven pyramids on Mauritius(g).

A 2020 article on the Ancient Origins website by Daniela Giordano reviews the subject of Italian pyramids and more particularly the Sicilian pyramids and their possible connection with the Shekelesh one of the Sea Peoples, an idea also advocated by Nancy K. Sanders, the British archaeologist. The article goes on to suggest some linkage with the more than controversial Bosnian pyramids, which I find overly speculative(k).

Quite recently a bronze object with a 13th century BC Sicilian connection was found off the coast of Devon in the UK, suggesting ancient trade between the Central Mediterranean and Britain(j).

(b) http://www.antikitera.net/news.asp?ID=9728

(c) http://www.thorwalds-internetseiten.de

(d) Archive 2006

(e) https://patrickofatlantis.com/

(f) https://www.gigalresearch.com/uk/pyramides-sicile.php

(g) https://www.gigalresearch.com/uk/pyramides-maurice.php

(h) http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/article00749.html

(i) https://www.bestofsicily.com/mag/art407.htm

(j) https://atlantisonline.smfforfree2.com/index.php?topic=5703.0;wap2

(k) https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/sicily-pyramids-0013233

Also See: Pantelleria