Hesperides

Honorius Augustodunensis

Honorius Augustodunensis (fl.1107-1140) was a popular German theologian and a prolific writer. The Catholic Encyclopaedia quotes the view that Honorius was one of the most mysterious personages in all the medieval period. In what is arguably his best known work, Imago Mundi(c), he expressed the view that Atlantis had been an island in the Atlantic (35. Sardinia). He wrote that that the ‘curdled sea’, assumed by Andrew Collins to be a reference to the Sargasso Sea[0072.91], “adjoins the Hesperides and covers the site of lost Atlantis, which lay west from Gibraltar.”

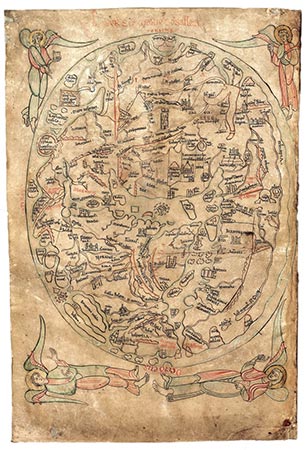

His Imago Mundi contained a world map, which has become known as The Sawley Map(b).

*(c) https://12koerbe.de/arche/imago.htm*

Rutot, Aimé-Louis (L)

Aimé-Louis Rutot (1847-1933) was a Belgian archaeologist who wrote extensively on  prehistoric civilisation. In 1920[533] he identified Agadir on the Atlantic coast of Morocco as the location of the capital city of Atlantis. He suggested that Lake Tritonis was a large inland sea where the chotts are today. He also proposed a further large ‘Inner Lake’ existed across Hauts Plateau in the Atlas Mountains of Algeria. Rutot further identified the island of Hesperides as a large section of what is now mainland Africa, opposite the Canaries, and formerly the site of the ancient city of Lixus.

prehistoric civilisation. In 1920[533] he identified Agadir on the Atlantic coast of Morocco as the location of the capital city of Atlantis. He suggested that Lake Tritonis was a large inland sea where the chotts are today. He also proposed a further large ‘Inner Lake’ existed across Hauts Plateau in the Atlas Mountains of Algeria. Rutot further identified the island of Hesperides as a large section of what is now mainland Africa, opposite the Canaries, and formerly the site of the ancient city of Lixus.

Hi-Brasil or Hy-Brasil

Hi–Brasil or Hy–Brasil is sometimes referred to as the Irish Atlantis and is a name given to a legendary island to the west of Ireland. It is frequently referred to as the Fortunate Island, which has obvious resonances with the Hesperides. Another appellation in Irish is Tir fo-Thuin or Land under the Wave. A further explanation offered for the origin of the name is that it is derived from an ancient term ‘brazil’ that refers to the source of a rare dye, which is reminiscent of the expensive purple dye extracted from the Murex snail, traded by the Phoenicians.

One theory is that in the dim and distant past a part of what is now known as the Porcupine Bank, just west of Ireland, was exposed when the sea levels were lower as a result of the last Ice Age. When the feature was submerged by the rising seas it was probably eroded further by the ocean currents. The claim is that a memory of the exposed land lingered in the folk memory of the inhabitants of the west coast of Ireland.

>Marin, Minella & Schievenin in The Three Ages of Atlantis [972.375] propose that the island of Thule described by Pytheas was the legendary Hi-Brasil, which, they further claim, was part of the Porcupine Bank that they describe as ‘recently submerged’.<

The Genoese cartographer, Angellino de Dalorto (fl.1339), placed Hy-Brasil west of Ireland on a map as early as 1325. However, on some 15th-century maps, the islands of the Azores appear as Isola de Brazil, or Insulla de Brazil. Apparently, it was not until as late as 1865 that Hy-Brasil was finally removed from official naval charts. Also found on medieval maps was another mystery island south of Brasil, sometimes appearing as Mayda, Asmaidas or Brazir(d).

Phantom islands have been shown on maps for hundreds of years and some as recently as the 20th century(f).

One of the most famous visits to Hy-Brasil was in 1674 by Captain John Nisbet of Killybegs, Co. Donegal, Ireland. He and his crew were in familiar waters west of Ireland, when a fog came up. As the fog lifted, the ship was dangerously close to rocks. While getting their bearings, the ship anchored in three fathoms of water, and four crew members rowed ashore to visit Hy-Brasil. They spent a day on the island and returned with silver and gold were given to them by an old man who lived there. Upon the return of the crew to Ireland, a second ship set out under the command of Alexander Johnson. They, too, found the hospitable island of Hy-Brasil and returned to Ireland to confirm the tales of Captain Nisbet and crew.

The last documented sighting of Hy-Brasil was in 1872 when author T. J. Westropp and several companions saw the island appear and then vanish. This was Westropp’s third view of Hy-Brasil, but on this voyage, he had brought his mother and some friends to verify its existence.

The Irish historian, W.G.Wood-Martin, also wrote[388.1.212] about Hi-Brazil over a hundred years ago.

Donald S. Johnson has also written an illustrated and more extensive account of the ‘history’ of Hi-Brazil in chapter six of his Phantom Islands of the Atlantic [652].

A modern twist on the story arose in connection with the Rendelsham UFO(b) mystery/hoax(c) of 1980 when coordinates that correspond to one of the Hy-Brasil locations were allegedly conveyed to one Sgt. Jim Penniston who kept it secret for thirty years(a)!

In 2010, the September 11th edition of the London Daily Mail (and its sister paper, the Irish Daily Mail) ran an article with the adventurous headline “The Atlantis of Connemara” that included the accounts of 20th-century witnesses to unexplained visions off the west coast of Galway. Included was a potted history of recorded sightings since 1460.

In 2013 Barbara Freitag published a valuable in-depth study[1331] of Hy-Brasil dealing with its cartography, history and mythology.

(b) The Rendlesham Forest UFO case – Ian Ridpath (archive.org)

(c) https://www.bbc.co.uk/insideout/east/series3/rendlesham_ufos.shtml

(d) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayda

(e) Archive 2272

(f) https://en.protothema.gr/a-list-of-various-phantom-islands-recorded-throughout-history/

Hesperides

The Hesperides in Greek mythology were the daughters of Atlas. They lived on an island in the far west guarding a tree that bore golden apples made famous in the story of the twelve labours of Hercules who was charged with obtaining some of the apples.

The Hesperides have also been referred to as the Fortunate Islands and is the name applied by classical writers to islands off the west coast of Africa that have been variously identified with the Azores, Canaries or Cape Verde islands. Other opinions place the garden at Gades or on the Atlantic coast of Morocco,> such as Pliny’s suggested location of Lixus(b).<

>According to Wikipedia “the Sicilian Greek poet Stesichorus, in his poem the “Song of Geryon”, and the Greek geographer Strabo, in his book Geographika (volume III), the garden of the Hesperides is located in Tartessos, a location placed in the south of the Iberian peninsula.”(c)<

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés writing in the 16th century [1117] considered the Antilles in the Caribbean to have been the legendary Isles of Hesperides.

While the majority opinion is that the name specifically refers to the Canaries, a minority view espoused by Andrew Collins[072](a) is similar to that of Oviedo, namely that Hesperides refers to the Caribbean, where he is convinced that Cuba had been the home of Atlantis.

>Reginald Fessenden argued that the Hesperides lay in the east not the west in chapter one of The Deluged Civilization of the Caucasus[1012].<

(a) https://www.grahamhancock.com/phorum/read.php?f=1&i=122922&t=122922

(b) Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis – Book V. *

(c) Hesperides – Wikipedia *

Hesiod

Hesiod was one of ancient Greece’s foremost poets and is generally assumed to have flourished around  750 BC. Two of his works have been identified as having parallels with Plato’s Atlantis. The first, his Works and Days, describes the deterioration of mankind in a similar manner to the moral decline of the inhabitants of Atlantis related by Plato.

750 BC. Two of his works have been identified as having parallels with Plato’s Atlantis. The first, his Works and Days, describes the deterioration of mankind in a similar manner to the moral decline of the inhabitants of Atlantis related by Plato.

The second, Theogony, prompted Haraldur Sigurdsson, a volcanologist has identified imagery that could be a reflection of the eruption of Thera seven hundred years earlier. Professors Mott Greene[575] and J. V. Luce among others support this idea. This poem contains in line 938 what is probably the earliest use of the name ‘Atlantis’ that we have. “And Maia, the daughter of Atlas, bare to Zeus glorious Hermes, the herald of the deathless gods, for she went up into his holy bed.”(a)

Greene lists fifteen details in Titanomachy and compares them with the characteristics of the mid 2nd millennium BC eruption of Thera and finds a remarkable correspondence (p.61/2).

The Titanomachy or the war between the Titans and the Olympians recorded in the Theogony has been perceived as a parallel of the conflict between Athens and Atlantis. He also refers to the Hesperides, identified by some with Atlantis, as being located in the west

In the same work Hesiod notes that a wall of bronze ran around Tartarus (equivalent to Hell in Greek mythology), which brings to mind the walls covered with orichalcum in Plato’s Atlantis. It is not unreasonable to suggest the possibility of a common inspiration for both.

(a) https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hesiod/theogony.htm

Martinez Hernandez, Marcos

Marcos Martinez Hernandez was born in the Canary Islands in 1945. He studied there at Laguna University and later at Madrid University where received a doctorate in Classical Philology. His academic career eventually brought him back to Laguna University where he held the Chair of Greek Philology from 1987 until 1999.

He has written a range of articles and books, with one on possible connections between The Canaries and Greek Mythology[384] including Plato’s Atlantis, Isles of the Blest and the Hesperides.

Flora and Fauna of Atlantis

The Flora and Fauna of Atlantis is mentioned in great detail by Plato in Critias;

“Besides all this, the earth bore freely all the aromatic substances it bears today, roots, herbs, bushes and gums exuded by flowers or fruit. There were cultivated crops, cereals which provide our staple diet. And pulse (to use its generic name) which we need in addition to feed us; there were the fruits of trees, hard to store but providing the drink and food and oil which gives us pleasure and relaxation and which we serve after supper as a welcome refreshment to the weary when appetite is satisfied – all these were produced by that sacred island, then still beneath the sun, in wonderful quality and profusion.” (115a-b)

James Bramwell noted how Leo Frobenius was convinced that his chosen Atlantis location of Yorubaland in Nigeria was reinforced by Plato’s description of the flora of his disappeared island [0195.119].

The lack of sufficient detail in the extract from Critias has led to a variety of interpretations. Jürgen Spanuth in support of his North Sea location for Atlantis has claimed [015.68] that during the Bronze Age the snow line in that region was higher than at any other time since the last Ice Age at 1,900 metres. He claims that as a result, grapes and wheat were cultivated there during that period.

The existence of the same species of plants and animals on both sides of the Atlantic has been noted for some time, so when the Mid Atlantic Ridge (MAR) was discovered in the 19th century and subsequently combined with the realisation that sea levels had dropped during the last Ice Age, it was thought that a stepping-stone/s, if not an actual landbridge, between the continents had been identified. This idea was popular with many geologists and botanists at the beginning of the 20th century, such R.F. Scharff and H.E. Forrest, both of whom also saw the MAR as the location of Atlantis, an idea that still persists today. Emmet Sweeney is a modern writer who also sees the earlier exposed MAR as an explanation for the shared transatlantic biota and is happy to identify the Azores as the last remnants of Atlantis[0700].

Andrew Collins has attempted to squeeze a reference to coconuts out of this text to support his Caribbean location for Atlantis. However, coconuts were not introduced into that region until colonial times(c). Ivar Zapp & George Erikson, driven by similar motivations had made the same claim earlier.

>Dhani Irwanto has noted that “DNA analysis of more than 1,300 coconuts from around the world reveals that the coconut was brought under cultivation in two separate locations, one in the Pacific basin and the other in the Indian Ocean basin. (Baudouin et al, 2008; Gunn et al, 2011).(d)“<

My reading of the text is that Plato is describing food with which he is personally familiar and is unlikely to have been referring to coconuts.

>Michael Hübner in support of his Moroccan location for Atlantis has drawn attention to the argan tree, native to Southern Morocco, from which a valuable oil is produced. He goes further and claims that the appearance of the fruit of the argan tree may also have been the source of the story of the ‘golden apples’ stolen by Hercules from the Hesperides. Critias 114e tells us how Atlantis “brought forth also in abundance all the timbers that a forest provides for the labours of carpenters”. Even today, across the northern regions of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, woodlands and forests still cover an area of nearly 360,000 square kilometers(e).<

Mary Settegast points out that around 7300 BC there is evidence of crop rotation including cereals at the Tell Aswad site in Syria.

The olive tree thrives best in regions with a Mediterranean climate. Olive trees are mainly found between 25° and 45° N. latitude, while in France, they are only found in its southern Mediterranean region.

Ignatius Donnelly devoted Chapter VI(a) of his Atlantis tome to a review of the Atlantean flora and fauna. The print media at the start of the 20th century kept the general public aware of these theories(b).

Those that believe that Plato’s Atlantis narrative was just an invention to promote Plato’s political philosophy cannot explain the level of detail that is provided relating to the flora and fauna of Atlantis. In Plato’s dialogue Laws, Magnesia, another ideal city-state, which was an invention, had no such embellishment included. For me, the minutiae of the plants and animals noted by Plato in Critias is not what you would expect in a philosophical or political dissertation, but is more in keeping with a factual report.

(a) https://www.sacred-texts.com/atl/ataw/ataw106.htm

(b) https://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/189397134?searchTerm=Atlantis discovered&searchLimits=

(d) Coconuts | Atlantis in the Java Sea (atlantisjavasea.com) *

(e) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mediterranean_woodlands_and_forests *

Erytheia

Erytheia, sometimes known as the ‘Red Isle’, is recorded by Hesiod (8th cent. BC) as one of the three Hesperides, a sunken island beyond the Pillars of Heracles. Pherecydes of Athens (5th cent. BC), is considered to be the first to identify Erytheia with Gádeira (Cadiz) according to Strabo (Geog. Bk. III). Some commentators have found many of its characteristics comparable with that of Plato’s Atlantis. Herodotus (Hist. 4.8) also describes it as an island that was located beyond the ‘Pillars’ near Gades. Avienus also supported this idea while Solinus described it as being on the Lusitanian coast (Portugal).

N. Zhirov agreed with Adolf Schulten in identifying Erytheia with Tartessos. However, while Schulten located Tartessos at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River in South West Spain, Zhirov argued that the story of Hercules taking from Erytheia, the oxen of Geryon, indicated a distance of around 60 miles from the coast. He points out that since Hercules had to get from Helios the ‘golden cup’ in order to show direction by day and night, it would not have required a compass had the island been close to land. Similarly, he reasoned that Erytheia could not have been more than one or two days journey since their small boat could not have carried enough food and water for the animals on a long journey.

Isla de León is a large piece of land between the city of Cádiz and the mainland and is accepted by some as having been the home of the mythical giant Geryon and his cattle.>Rhys Carpenter identified Isla de León as Erytheia. [221]<

Controversially, Gades(a) and Erytheia(b) have both been placed on the Map Mistress website in the Central Mediterranean and since they have both been associated with the ‘Pillars of Heracles’, is she suggesting a location in that region for Atlantis?

A paper on the subject was presented to the 2005 Atlantis conference on Melos, by Papamarinopoulos, N. Drivaliari & Ch. Cosyan also places Erytheia in the vicinity of Cadiz.[629.540]

>Pamina Fernandez Camacho, a Spanish philologist, offers a detailed study(c) of Erytheia in which she concludes that it is “a mythical name attributed to a real place, Gádeira, modern Cadiz.(c)<

(a) http://www.mapmistress.com/egadi-islands-marettimo-levanzo-favignana.html (link broke Dec 2020) Text only available at Egadi Islands: Marettimo, Levanzo, Favignana of Sicily (archive.org)

(b) http://www.mapmistress.com/pantelleria-erytheia-sicily-tunisia.html (link broke Dec 2020) Text only available at Pantelleria & Erytheia: Southwest Sicily Sunken Coastline to Tunisia (archive.org)

Classical Writers Supporting the Existence of Atlantis

Classical Writers Supporting the Existence of Atlantis

Although many of the early writers are quoted as referring to Plato’s Atlantis or at least alluding to places or events that could be related to his story there is no writer who can be identified as providing unambiguous independent evidence for Atlantis’ existence. One explanation could be that Atlantis may have been known by different names to different peoples in different ages, just as the Roman city of Aquisgranum was later known as Aachen to the Germans and concurrently as Aix-la-Chapelle to the French. However, it would have been quite different if the majority of post-Platonic writers had completely ignored or hotly disputed the veracity of Plato’s tale.

Sprague de Camp, a devout Atlantis sceptic, included 35 pages of references to Atlantis by classical writers in Appendix A to his Lost Continents.[194.288]

Alan Cameron, another Atlantis sceptic, is adamant that ”it is only in modern times that people have taken the Atlantis story seriously, no one did so in antiquity.” Both statements are clearly wrong, as can be seen from the list below and my Chronology of Atlantis Theories and even more comprehensively by Thorwald C. Franke’s Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis (Critical history of the hypotheses on Plato’s Atlantis)[1255].

H.S. Bellamy mentions that about 100 Atlantis references are to be found in post-Platonic classical literature. He also argues that if Plato “had put forward a merely invented story in the Timaeus and Critias Dialogues the reaction of his contemporaries and immediate followers would have been rather more critical.” Thorwald C. Franke echoes this in his Aristotle and Atlantis[880.46]. Bellamy also notes that Sais, where the story originated, was in some ways a Greek city having regular contacts with Athens and should therefore have generated some denial from the priests if the Atlantis tale had been untrue.

Homer(c.8thcent. BC)wrote in his famous Odyssey of a Phoenician island called Scheria that many writers have controversially identified as Atlantis. It could be argued that this is another example of different names being applied to the same location.

Hesiod (c.700 BC) wrote in his Theogonyof the Hesperides located in the west. Some researchers have identified the Hesperides as Atlantis.

Herodotus (c.484-420 BC)regarded by some as the greatest historian of the ancients, wrote about the mysterious island civilization in the Atlantic.

Hellanicus of Lesbos (5th cent. BC) refers to ‘Atlantias’. Timothy Ganz highlights[0376] one line in the few fragments we have from Hellanicus as being particularly noteworthy, “Poseidon mated with Celaeno, and their son Lycus was settled by his father in the Isles of the Blest and made immortal.”

Thucydides (c.460-400 BC)refers to the dominance of the Minoan empire in the Aegean.

Syrianus (died c.437 BC) the Neoplatonist and one-time head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, considered Atlantis to be a historical fact. He wrote a commentary on Timaeus, now lost, but his views are recorded by Proclus.

Eumelos of Cyrene (c.400 BC) was a historian and contemporary of Plato who placed Atlantis in the Central Mediterranean between Libya and Sicily.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Plato’s pupil is constantly quoted in connection with his alleged criticism of Plato’s story. This claim was not made until 1819 when Delambre misinterpreted a commentary on Strabo by Isaac Casaubon. This error has been totally refuted by Thorwald C. Franke[880]. Furthermore, it was Aristotle who stated that the Phoenicians knew of a large island in the Atlantic known as ’Antilia’. Crantor (4th-3rdcent. BC) was Plato’s first editor, who reported visiting Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis. However, Jason Colavito has pointed out that according to Proclus, Crantor was only told by the Egyptian priests that the carved pillars were still in existence.

Crantor (4th-3rd cent. BC) was Plato’s first editor, who reportedly visited Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis. However, Jason Colavito has pointed out(a) that according to Proclus, Crantor was only told by the Egyptian priests that the carved pillars were still in existence.

Theophrastus of Lesbos (370-287 BC) refers to colonies of Atlantis in the sea.

Theopompos of Chios (born c.380 BC), a Greek historian – wrote of the huge size of Atlantis and its cities of Machimum and Eusebius and a golden age free from disease and manual labour. Zhirov states[458.38/9] that Theopompos was considered a fabulist.

Apollodorus of Athens (fl. 140 BC) who was a pupil of Aristarchus of Samothrace (217-145 BC) wrote “Poseidon was very wrathful, and flooded the Thraisian plain, and submerged Attica under sea-water.” Bibliotheca, (III, 14, 1.)

Poseidonius (135-51 BC.) was Cicero’s teacher and wrote, “There were legends that beyond the Hercules Stones there was a huge area which was called “Poseidonis” or “Atlanta”

Diodorus Siculus (1stcent. BC), the Sicilian writer who has made a number of references to Atlantis.

Marcellus (c.100 BC) in his Ethiopic History quoted by Proclus [Zhirov p.40] refers to Atlantis as consisting of seven large and three smaller islands.

Statius Sebosus (c. 50 BC), the Roman geographer, tells us that it was forty days’ sail from the Gorgades (the Cape Verdes) and the Hesperides (the Islands of the Ladies of the West, unquestionably the Caribbean – see Gateway to Atlantis).

Timagenus (c.55 BC), a Greek historian wrote of the war between Atlantis and Europe and noted that some of the ancient tribes in France claimed it as their original home. There is some dispute about the French druids’ claim.

Philo of Alexandria (b.15 BC) also known as Philo Judaeus also accepted the reality of Atlantis’ existence.

Strabo (67 BC-23 AD) in his Geographia stated that he fully agreed with Plato’s assertion that Atlantis was fact rather than fiction.

Plutarch (46-119 AD) wrote about the lost continent in his book Lives, he recorded that both the Phoenicians and the Greeks had visited this island which lay on the west end of the Atlantic.

Pliny the Younger (61-113 AD) is quoted by Frank Joseph as recording the existence of numerous sandbanks outside the Pillars of Hercules as late as 100 AD.

Tertullian (160-220 AD) associated the inundation of Atlantis with Noah’s flood.

Claudius Aelian (170-235 AD) referred to Atlantis in his work The Nature of Animals.

Arnobius (4thcent. AD.), a Christian bishop, is frequently quoted as accepting the reality of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395 AD) [see Marcellinus entry]

Proclus Lycaeus (410-485 AD), a representative of the Neo-Platonic philosophy, recorded that there were several islands west of Europe. The inhabitants of these islands, he proceeds, remember a huge island that they all came from and which had been swallowed up by the sea. He also writes that the Greek philosopher Crantor saw the pillar with the hieroglyphic inscriptions, which told the story of Atlantis.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (6thcent. AD), a Byzantine geographer, in his Topographica Christiana (547 AD) quotes the Greek Historian, Timaeus (345-250 BC) who wrote of the ten kings of Chaldea [Zhirov p.40]. Marjorie Braymer[198.30] wrote that Cosmas was the first to use Plato’s Atlantis to support the veracity of the Bible.

There was little discussion of Atlantis after the 6th century until the Latin translation of Plato’s work by Marsilio Ficino was produced in the 15th century.

(a) https://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/the-first-believer-why-early-atlantis-testimony-is-suspect

Avalon

Avalon is the legendary resting place of Britain’s King Arthur. Tradition has it that it was also famous for its apples and this feature led some to link it with the legend of the Hesperides considered another name for Atlantis. This linkage of Avalon with Atlantis is extremely tenuous. The apple connection is also suggested by the Welsh for Avalon which is Ynys Afallon, possibly derived from afal, the Welsh for apple.

Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historiae (xxxvii.35) named Helgoland as ‘insulam Abalum’, which has been suggested as a variant of Avalon. Other locations such as Sicily and Avallon in Burgundy have been also been proposed. A series of YouTube clips(a) bravely links Avalon, Mt.Meru and Atlantis, which is supposedly situated in the Arctic!

The isle of Lundy in Britain’s Bristol Channel has been speculatively identified as Avalon(b).>Other leading contenders are the Isle of Man and Glastonbury(c).<

(a) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xrSr594L70c