Rainer Kuhne

National Geographic *

National Geographic or Nat Geo are the registered trademarks of the National Geographic Society and are now, sadly, part of the Murdoch communications empire. Its magazine and TV channel enjoy global recognition. Undoubtedly, NG has enhanced our view of the world around us. One piece of NG trivia is that the word ‘tsunami’ first appeared in an English language publication in the September 1896 edition of National Geographic Magazine.

In May 1922 NG published its first picture of Stonehenge, now a century later it returned to this remarkable monument for its cover story in its August 2022 edition. It highlights how the use of new technologies has greatly enhanced our knowledge of the site and the people who built it. Jim Leary, a lecturer in field archaeology at the University of York admits that “a lot of the things we were taught as undergraduates in the 1990s we know now simply aren’t true.” This beautifully illustrated article is a useful update on developments at this huge UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Generally, NG has avoided controversy, but not always(a), so it will be interesting to see how its new chief James Murdoch, a climate change denier(b), will deal with the NG views on the subject up ’til now(c). However, for me, it was something of a surprise when NG tackled the subject of Atlantis.

In 2004 NG News published a short article(d) highlighting the theories of Ulf Erlingsson and Rainer Kühne, who, respectively, were advocates for Ireland and Spain as Atlantis locations. Also in 2004, Zeilitsky and Weinzweig claimed to have found submerged man-made structures near Cuba and subsequently sought US government funding for further research there. It has been suggested that NG objected and further exploration did not take place! In 2006 NG gave the Atlantis in America theory of Zapp & Erikson an airing(e).

However, in 2012, Andrew Collins offered a different account of the Zelitsky funding difficulties(m).

In a short 2011 article(l)., NG trotted out the now generally abandoned idea that Atlantis had been a continent. The idea was obviously later dumped by NG as well when James Cameron et al. went looking for Atlantis in Malta, Sardinia and Santorini in 2016.

December 2012 saw NG publish an article on Doggerland, without any reference to the suggestion that there might be an Atlantis connection. NG has also voiced the scepticism of well-known commentators, such as Robert Ballard and Charles E. Orser jnr(f).

However, I find that the NG treatment of Atlantis is inconsistent. In October 2011 an anonymous article(k) on one of their sites, entitled The Truth Behind Atlantis: Facts, declared that Atlantis was continental in size (and so must have been located in an Ocean?) This is based on a misinterpretation of the Greek word meison. Nevertheless last year NG had Simcha Jacobovici, remotely guided by James Cameron, scouring the Mediterranean, from Spain to Sardinia, Malta, and Crete for evidence of Atlantis. This attention-seeking exercise found nothing but a few stone anchors that proved nothing and inflicted on viewers an overdose of speculation!

NatGeo TV aired a documentary(g) in 2015 relating to earlier excavations in the Doñana Marshes of Southern Spain by a Spanish team and partly hijacked by Richard Freund. A new NG documentary, hyped with the involvement of James Cameron and Simcha Jacobovici, was filmed in 2016, and later broadcast at the end of January 2017. Initially, it was thought by Robert Ishoy to be in support of his Atlantis location of Sardinia, but at the same time, Diaz-Montexano was convinced that his Afro-Iberian theory was to be the focus of the film. To coincide with the airing of the new documentary D-M has published a new book, NG National Geographic and the scientific search for Atlantis[1394] with both English and Spanish editions.

Jason Colavito was promised a screener but had the offer subsequently withdrawn. One wonders why.

Once again NG promotes the region of the Doñana Marshes as a possible location for Atlantis(i), based on rather flimsy evidence, such as six ancient anchors found just outside the Strait of Gibraltar. They estimate the age of the anchors at 3,000-4,000 years old. unfortunately, they are not marked ‘made in Atlantis’. Rabbi Richard Freund, never afraid to blow his own shofar, makes another NG appearance. Jacobovici throws in the extraordinary claim that the Jewish menorah represents the concentric circles of the Atlantean capital cut in half, a daft idea, previously suggested by Prof. Yahya Ababni(k).

What I cannot understand is why this documentary spends time dismissing Santorini and Malta as possible locations for Plato’s Atlantis and at the same time ignoring the only unambiguous geographical clue that he left us, namely that the Atlantis alliance occupied part of North Africa and in Europe the Italian peninsula as far as Tyrrhenia (Tuscany) and presumably some of the islands between the two.

Overall, I think the NG documentaries have done little to advance the search for Atlantis as they seem to be driven by TV ratings ahead of the truth. Perhaps, more revealing is that Cameron is not fully convinced by the speculative conclusions of his own documentary.

Jason Colavito, an arch-sceptic regarding Atlantis has now published a lengthy scathing review(j) of NG’s Atlantis Rising, which is well worth a read. While I do not agree with Colavito’s dismissal of the existence of Atlantis, I do endorse the litany of shortcomings he identified in this documentary.

For me, NG’s credibility as a TV documentary maker has diminished in recent years. Just one reason is the “2010 National Geographic Channel programme, 2012: The Final Prophecy, enthused about an illustration in the Mayan document known as the Dresden Codex (because of where it is now kept), which was claimed to show evidence of a catastrophic flood bringing the world to an end in 2012. This illustration included a representation of a dragon-like figure in the sky spewing water from its mouth onto the Earth beneath, which has been taken by some, although by no means all, experts in Mesoamerican mythology to indicate the onset of a terminal world-flood. However, no date was given, so the link with 2012 is entirely spurious (Handwerk, 2009; Hoopes, 2011).”(n)

(a) National Geographic Shoots Itself in the Foot — Again! (archive.org)

(b) https://gizmodo.com/national-geographic-is-now-owned-by-a-climate-denier-1729683793

(d) See: Archive 3582

(e) https://www.dcourier.com/news/2006/oct/02/atlantis-theory-by-local-anthropologist-makes-nat/ (not available in EU) *

(f) http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/archaeology/atlantis/

(g) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyEY0tROZgI & https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=choIyaPiMjo

(h) https://mosestablet.info/en/menorah-tablet.html

(l) https://channel.nationalgeographic.com/the-truth-behind/articles/the-truth-behind-atlantis-facts/

(m) https://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread374842/pg11

(n) Doomsday Cults and Recent Quantavolutions, by Trevor Palmer (q-mag.org) (about 2/3rds down page)

Late Bronze Age Collapse

Late Bronze Age Collapse of civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC has been variously attributed to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and severe climate change. It is extremely unlikely that all these occurred around the same time through coincidence. Unfortunately, it is not clear to what extent these events were interrelated. As I see it, political upheavals do not lead to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or drought and so can be safely viewed as an effect rather than a cause. Similarly, climate change is just as unlikely to have caused eruptions or seismic activity and so can also be classified as an effect. Consequently, we are left with earthquakes and volcanoes as the prime suspects for the catastrophic turmoil that took place in the Middle East between the 15th and 12th centuries BC. Nevertheless, August 2013 saw further evidence published that also blamed climate change for the demise of Bronze Age civilisations in the region.

In 2022, a fourth possible cause emerged from a genetic research project -disease. The two disease carriers in question were the bacteria Salmonella enterica, which causes typhoid fever, and the infamous Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for the Black Death plague that decimated the population of medieval Europe. These are two of the deadliest microbes human beings have ever encountered, and their presence could have easily triggered significant heavy population loss and rampant social upheaval in ancient societies(d).

Robert Drews[865] dismisses any suggestion that Greece suffered a critical drought around 1200 BC, citing the absence of any supporting reference by Homer or Hesiod as evidence. He proposes that “the transition from chariot to infantry warfare as the primary cause of the Great Kingdoms’ downfall.”

Diodorus Siculus describes a great seismic upheaval in 1250 BC which caused radical topographical changes from the Gulf of Gabes to the Atlantic. (181.16)

This extended period of chaos began around 1450 BC when the eruptions on Thera took place. These caused the well-documented devastation in the region including the ending of the Minoan civilisation and probably the Exodus of the Bible and the Plagues of Egypt as well. According to the Parian Marble, the Flood of Deucalion probably took place around the same time.

Professor Stavros Papamarinopoulos has written of the ‘seismic storm’ that beset the Eastern Mediterranean between 1225 and 1175 BC(a). Similar ideas have been expressed by Amos Nur & Eric H.Cline(b)(c). The invasion of the Sea Peoples recorded by the Egyptians, and parts of Plato’s Atlantis story all appear to have taken place around this same period. Plato refers to a spring on the Athenian acropolis (Crit.112d) that was destroyed during an earthquake. Rainer Kühne notes that this spring only existed for about 25 years but was rediscovered by the Swedish archaeologist, Oscar Broneer, who excavated there from 1959 to 1967. The destruction of the spring and barracks, by an earthquake, was confirmed as having occurring at the end of the 12th century BC. Tony Petrangelo published two interesting, if overlapping, articles in 2020 in which he discussed Broneer’s work on the Acropolis(e)(f).

>A recent review of two books on subject in the journal Antiquity begins with the following preamble;

“The collapse c.1200 BC’ in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean—which saw the end of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Hittite state and its empire and the kingdom of Ugarit—has intrigued archaeologists for decades. As Jesse Millek points out in (his book) Destruction and its impact, the idea of a swathe of near-synchronous destructions across the eastern Mediterranean is central to the narrative of the Late Bronze Age collapse: “destruction stands as the physical manifestation of the end of the Bronze Age” (p.6). Yet whether there was a single collapse marked by a widespread destruction horizon is up for debate.” (g)<

(b) https://academia.edu/355163/2001_Nur_and_Cline_Archaeology_Odyssey_Earthquake_Storms_article (this is a shorter version of (c) below)

(e) https://atlantis.fyi/blog/platos-fountain-on-the-athens-acropolis

(f) A General Program of Defense | Atlantis FYI

(g) Getting closer to the Late Bronze Age collapse in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean, c. 1200 BC | Antiquity | Cambridge Core*

Wilkens, Iman Jacob

Iman Jacob Wilkens (1936- ) was born in the Netherlands but worked in France as an economist until retiring in 1996. In 1990 he threw a cat among the pigeons when he published Where Troy Once Stood[610] which located  Troy near Cambridge in England and identified Homer’s Trojan War as an extensive conflict in northwest Europe. He follows the work of Belgian lawyer, Théophile Cailleux[393], who presented similar ideas at the end of the 19th century just before Schliemann located his Troy in western Turkey, pushing Cailleux’s theories into obscurity until Wilken’s book a century later. The Cambridge location for Troy has recently been endorsed in a book by Bernard Jones [1638].

Troy near Cambridge in England and identified Homer’s Trojan War as an extensive conflict in northwest Europe. He follows the work of Belgian lawyer, Théophile Cailleux[393], who presented similar ideas at the end of the 19th century just before Schliemann located his Troy in western Turkey, pushing Cailleux’s theories into obscurity until Wilken’s book a century later. The Cambridge location for Troy has recently been endorsed in a book by Bernard Jones [1638].

Wilkens is arguably the best-known proponent of a North Atlantic Troy, which he places in Britain. Another scholar, who argues strongly for Homer’s geographical references being identifiable in the Atlantic, is Gerard Janssen of the University of Leiden, who has published a number of papers on the subject(d).

>It is worth noting that the renowned Moses Finley also found weaknesses in Schliemann’s identification of Hissalik as Troy(f). This is expanded on in Aspects of Antiquity [1953].<

Felice Vinci also gave Homer’s epic a northern European backdrop locating the action in the Baltic[019]. Like Wilkens, he makes a credible case and explains that an invasion of the Eastern Mediterranean by northern Europeans also brought with them their histories as well as place names that were adopted by local writers, such as Homer.

Wilkens claims that the invaders can be identified as the Sea Peoples and were also known as Achaeans and Pelasgians who settled the Aegean and mainland Greece. This matches Spanuth’s identification of the Sea Peoples recorded by the Egyptians as originating in the North Sea. Spanuth went further and claimed that those North Sea Peoples were in fact the Atlanteans.

Wilkens’ original book had a supporting website(a), as does the 2005 edition (b) as well as a companion DVD. A lecture entitled The Trojan Kings of England is also available online(c).

A review of Wilkens’ book by Emilio Spedicato is available online(e).

(a) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20170918084923/https://where-troy-once-stood.co.uk/

(b) See: https://web.archive.org/web/20191121230959/https://www.troy-in-england.co.uk/

(c) http://phdamste.tripod.com/trojan.html

(d) https://leidenuniv.academia.edu/GerardJanssen

Tartessos *

Tartessos or Tartessus is generally accepted to have existed along the valley of the Guadalquivir River where the rich deposits of copper and silver led to the development of a powerful native civilisation, which traded with the Phoenicians, who had colonies along the south coast of Spain(k).

A continuing debate is whether Tartessos was developed by a pre-Phoenician indigenous society or was a joint venture by locals along with the Phoenicians.(o) One of the few modern English-language books about Tartessos was written by Sebastian Celestino & Carolina López-Ruiz and entitled Tartessos and the Phoenicians in Iberia [1900].

A 2022 BBC article offers some additional up-to-date developments in the studies of Tartessos(v).

It is assumed by most commentators that Tartessos was identical to the wealthy city of Tarshish that is mentioned in the Bible. There have been persistent attempts over the past century to link Tartessos with Atlantis. The last king of Tartessia, in what is now Southern Spain, is noted by Herodotus to have been Arganthonios, who is claimed to have ruled from 630 BC until 550 BC. Similarly, Ephorus a 4th century BC historian describes Tartessos as ‘a very prosperous market.’ However, if these dates are only approximately true, then Atlantis cannot be identified with Tartessos as they nearly coincide with the lifetime of Solon, who received the story of Atlantis as being very ancient.

However, the suggested linkage of Tartessos with Atlantis is disputed by some Spanish researchers, such as Mario Mas Fenollar [1802] and Ester Rodríguez González(n). Mas Fennolar has claimed that at least a thousand years separated the two. Arysio dos Santos frequently claimed that Atlantis was Tartessos throughout his Atlantis and the Pillars of Hercules [1378].

The existence of a ‘Tartessian’ empire is receiving gradual acceptance. Strabo writes of their system of canals running from the Guadalquivir River and a culture that had written records dating back 6,000 years. Their alphabet was slightly different to the ‘Iberian’. The Carthaginians were said to have been captured by Tartessos after the reign of Arganthonios and after that, contact with Tartessos seems to have ended abruptly!

The exact location of this city is not known apart from being near the mouth of the Guadalquivir River in Andalusia. The Guadalquivir was known as Baetis by the Romans and Tartessos to the Greeks. The present-day Gulf of Cadiz was known as Tartessius Sinus (Gulf of Tartessus) in Roman times. Cadiz is accepted to be a corruption of Gades that in turn is believed to have been named after Gaderius. This idea was proposed as early as 1634 by Rodrigo Caro (image left), the Spanish historian and poet, in his Antigüedades y principado de la Ilustrísima ciudad de Sevilla, now available as a free ebook(i).

In 1849, the German researcher Gustav Moritz Redslob (1804-1882) carried out a study of everything available relating to Tartessos and concluded that the lost city had been the town of Tortosa on the River Ebro situated near Tarragona in Catalonia. The idea seems to have received little support until recently, when Carles Camp published a paper supporting this contention(w). It was written in Valenciano, which is related to Catalan and can be translated with Google Translate using the latter option.

A few years ago, Richard Cassaro endeavoured to link the megalithic walls of old Tarragona with the mythical one-eyed Cyclops and for good measure suggest a link with Atlantis(l). Concerning the giants, the images of doorways posted by Cassaro are too low to comfortably accommodate giants! Cassaro has previously made the same claim about megalithic structures in Italy(m)

The German archaeologist Adolf Schulten spent many years searching unsuccessfully for Tartessos, in the region of the Guadalquivir. He believed that Tartessos had been founded by Lydians in 1150 BC, which became the centre of an ancient culture that was Atlantis or at least one of its colonies. Schulten also noted that Tartessos disappeared from historical records around 500 BC, which is after Solon’s visit to Egypt and so could not have been Atlantis.

Richard Hennig in the 1920s also supported the idea of Tartessos being Atlantis and situated in southern Spain. However, according to Atlantisforschung he later changed his opinion opting to adopt Spanuth’s Helgoland location instead(x).

Otto Jessen, a German geographer, also believed that there had been a connection between Atlantis and Tartessos. Jean Gattefosse was convinced that the Pillars of Heracles were at Tartessos, which he identifies as modern Seville. However, Mrs E. M. Whishaw, who studied in the area for 25 years at the beginning of the 20th century, believed that Tartessos was just a colony of Atlantis. The discovery of a ‘sun temple’ 8 meters under the streets of Seville led Mrs Whishaw to surmise[053] that Tartessos may be buried under that city. Edwin Björkman wrote a short book, The Search for Atlantis[181] in which he identified Atlantis with Tartessos and also Homer’s Scheria.

book, The Search for Atlantis[181] in which he identified Atlantis with Tartessos and also Homer’s Scheria.

Steven A. Arts, the author of Mystery Airships in the Sky, also penned an article for Atlantis Rising in which he suggests that the Tarshish of the Old Testament is a reference to Tartessos and by extension to Atlantis(r)!

More recently Karl Jürgen Hepke has written at length, on his website(a), about Tartessos. Dr Rainer W. Kühne, following the work of another German, Werner Wickboldt, had an article[429] published in Antiquity that highlighted satellite images of the Guadalquivir valley that he has identified as a possible location for Atlantis. Kühne published an article(b) outlining his reasons for identifying Tartessos as the model for Plato’s Atlantis.

Although there is a consensus that Tartessos was located in Iberia, there have been some refinements of the idea. One of these is the opinion of Peter Daughtrey, expressed in his book, Atlantis and the Silver City[0893] in which he proposes that Tartessos was a state which extended from Gibraltar around the coast to include what is today Cadiz and on into Portugal’s Algarve having Silves as its ancient capital.

It was reported(c) in January 2010 that researchers were investigating the site in the Doñana National Park, at the mouth of the Guadalquivir, identified by Dr Rainer Kühne as Atlantis in a 2011 paper(s). In the same year, Professor Richard Freund of the University of Hartford garnered a lot of publicity when he visited the site and expressed the view that it was the location of Tartessos which he equates with Atlantis. The Jerusalem Post in seeking to give more balance to the discussion quoted archaeology professor Aren Maeir who commented that “Richard Freund is known as someone who makes ‘sensational’ finds. I would say that I am exceptionally skeptical about the thing, but I wouldn’t discount it 100% until I see the details, which haven’t been published as far as I know.”(u)

A minority view is that Tarshish is related to Tarxien (Tarshin) in Malta, which, however, is located some miles inland with no connection to the sea. Another unusual theory is offered by Luana Monte, who has opted for Thera as Tartessos. She bases this view on a rather convoluted etymology(e) which morphed its original name of Therasia into Therasios, which in Semitic languages having no vowels would read as ‘t.r.s.s’ and can be equated with Tarshish in the Bible, which in turn is generally accepted to refer to Tartessos.

Giorgio Valdés favours a Sardinian location for Tartessos(f), an idea endorsed later by Giuseppe Mura in his 2018 book, published in Italian, Tartesso in Sardegna [2068], the full title of which translates as Tartessos in Sardinia: Reasons, circumstances and methods used by ancient historians and geographers to remove Tartessos (the Tarshish of the Bible) from Caralis and place it in Spanish Andalusia. Caralis is an old name for Cagliari, the Sardinian capital.

Andis Kaulins has claimed that further south, in the same region, Carthage was possibly built on the remains of Tartessos, near the Pillars of Heracles(j).

A more radical idea was put forward in 2012 by the Spanish researcher, José Angel Hernández, who proposed(g)(h) that the Tarshish of the Bible was to be found in the coastal region of the Indus Valley, but that Tartessos was a colony of the Indus city of Lhotal and had been situated on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar!

A recent novel by C.E. Albertson[130] uses the idea of an Atlantean Tartessos as a backdrop to the plot.

A relatively recent claim associating Tartessos with Atlantis came from Simcha Jacobovici in a promotional interview(p) for the 2017 National Geographic documentary, Atlantis Rising. In it, Jacobovici was joined by James Cameron as producer, but unfortunately, the documentary did not produce anything of any real substance despite a lot of pre-broadcast hype.

There is an extensive website(d) dealing with all aspects of Tartessos, including the full text of Schulten’s book on the city. Although this site is in Spanish, it is worthwhile using your Google translator to read an English version.

“Today, researchers consider Tartessos to be the Western Mediterranean’s first historical civilization. Now, at an excavation in Extremadura—a region of Spain that borders Portugal, just north of Seville—a new understanding of how that civilization may have ended is emerging from the orange and yellow soil. But the site, Casas del Turuñuelo, is also uncovering new questions.”(q) First surveyed in 2014 it was in late 2021, a report emerged of exciting excavations there that may have a bearing on the demise of Tartessos. Work is currently on hold because of a dispute with landowners, with only a quarter of the site uncovered. The project director is Sebastian Celestino Perez. The Atlas Obscura website offers further background and details of discoveries at the site(t).

(a) http://web.archive.org/web/20170716221143/http://www.tolos.de/History%20E.htm

(b) Meine Homepage (archive.org)

(d) TARTESSOS.INFO: LA IBERIA BEREBER (archive.org)

(e) http://xmx.forumcommunity.net/?t=948627&st=105

(f) http://gianfrancopintore.blogspot.ie/2010/09/atlantide-e-tartesso-tra-mito-e-realta.html

(g) http://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/mito-y-religion/

(h) http://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/arqueologia-e-historia/

(j) Pillars of Heracles – Alternative Location (archive.org)

(k) Archive 3283 | (atlantipedia.ie)

(n) (PDF) Tarteso vs la Atlántida: un debate que trasciende al mito (researchgate.net)

(o) (PDF) Definiendo Tarteso: indígenas y fenicios (researchgate.net)

(p) Lost City of Atlantis And Its Incredible Connection to Jewish Temple (israel365news.com)

(q) The Ancient People Who Burned Their Culture to the Ground – Atlas Obscura

(r) Atlantis Rising magazine #36 http://pdfarchive.info/index.php?pages/At

(t) https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/tartessos-casas-del-turunuelo

(u) https://www.jpost.com/jewish-world/jewish-news/the-deepest-jewish-encampment

(v) https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20220727-the-iberian-civilisation-that-vanished

(w) https://www.inh.cat/articles/La-localitzacio-de-Tartessos-es-desconeguda.-Pot-ser-Tartessos-Tortosa-

(x) Richard Hennig – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

Stade *

The Stade was an ancient Greek measurement of distance. The origins of the stade are not clear. One opinion claims that at first, it was the distance covered by a plough before turning. Later it was the length of a foot race in a Greek Stadion (Roman Stadium) or 157 meters. Different ‘standard’ stadia existed in various city-states of ancient Greece ranging from 157 to 211 meters.

Some commentators have treated the stade as a synonym for the British ‘furlong’ (one eight a mile or 220 yards – approximately 201 metres), which was an old Anglo-Saxon measure for a ‘long furrow’.

Nick Kollerstrom has published a paper on Graham Hancock’s website arguing that “Mother Earth was clearly the source of the Greek stade, though the ancient Greek philosophers do not seem to have been aware of this fact.”(e)

Most commentators on Plato’s Atlantis seem to accept a value of 185 metres (607 feet) to the stade. Thorwald C.Franke argues for a value of 176 metres – ” It is confusing: The building called “stadion” had been 185 meters, but the measure “stadion” not. We can conclude that the Athenians once had a shorter building, but decided to build a bigger building in later times. It is the same story for the “stadion” of other cities.” (private correspondence)

The problem that has arisen is that irrespective of whichever stade was used by Plato, the resulting dimensions suggested by him are unacceptably large. This has led quite a number of commentators to suggest that Plato’s use of the stade was possibly due to some misunderstanding or transcription error and have striven to find a more credible unit of measurement.

Jim Allen who is the leading advocate for a Bolivian location for Atlantis has used a value for the stade that is half the conventionally accepted 185 metres. He bases this on the fact that the ancient South Americans used a base of 20 rather than 10 for counting. He offers an interesting article with impressive images on his website(a) in support of his contention.

Dr Rainer Kühne, who recently publicised that a site in Andalusia, identified by Werner Wickboldt from satellite photos, suggested that Plato used a stade that was probably 20% longer than what is normally accepted since the dimensions of the Spanish site are greater than those given in Plato’s text. This idea is not satisfactory as so many other dimensions of the city’s features already suggest over-engineering on a colossal scale. To add a further 20% would be even more ridiculous.

If the dimensions of Atlantis did originate on the pillars in the temple at Sais, the unit of measurement used was probably Egyptian (or Atlantean) and so their exact value must be open to question. The values given by Plato relating to Atlantis have long been ammunition for sceptics. They argue that Plato’s topographical data suggests either a degree of over-engineering that was improbable in the Bronze Age or impossible in the Stone Age and must, therefore, be a fantasy.

In the 1930s and 1940s, there was a degree of confusion among those reluctant to accept that the Greek ‘stade’ was a reliable unit of measurement for the architectural features described by Plato in Atlantis. Alexander Braghine in 1940, seems to have the matter entirely confused when he wrote [156.58] about Albert Hermann‘s proposal of 1934 that the unit of measurement used by the Egyptians to describe Atlantis was the ‘shoinos’, which Braghine noted is 604 times shorter than a stade, which is completely wrong or just a misprint that should read 60! Earlier in 1937 James Bramwell also commented on Hermann’s suggestion that it was the Egyptian ‘schoinos’, which is equivalent to 30 stadia [195.117].

William Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, noted that “SCHOENUS (?, ?, ???????), literally, a rope of rushes, an Egyptian and Persian itinerary and land measure (Herod. i. 66). Its length is stated by Herodotus (ii. 6, 9) at 60 stadia, or 2 parasangs; by Eratosthenes at 40 stadia, and by others at 112 or 30. (Plin. H. N. v. 9. s. 10, xii. 14. s. 30.) Strabo and Pliny both state that the schoenus varied in different parts of Egypt and Persia. (Strabo, p. 803; Plin. H. N. vi. 26. s 30; comp Athen. iii. p. 122, a.) [–Phillip Smith]”

An award-winning paper by Newly Walkup discusses in detail Eratosthenes attempt to measure the circumference of the Earth(f).

Today, Wikipedia proposes a conversion rate of 40 schoeni to the stade(c).

The late Ulf Richter proposed a simple solution to this problem(b), namely that the unit of measurement originally recorded was the Egyptian Khet. This was equivalent to 52.4 metres or approximately 3.5 times less than the value of the stade. The acceptance of this rational explanation removes one of the great objections to the veracity of the Atlantis narrative.

The most recent entrant into this particular debate is M.P. Courville [1960.10] who has proposed that Plato intended to use the plethrum, which is around 30 metres long or very roughly one-fifth the length of a stade. The problem arising from that idea is that Plato also uses the plethrum together with the stade in contexts where they both seem too large (Crit.116a & 118c)!

Jean-Pierre Pätznick commented in a paper on the Academia.edu website that “the 10,000-stadia ditch that would have surrounded the great plain on three sides would in fact have measured 1850 km long, 30.80 m deep and 185 m wide. A colossal structure that would have been 23 times larger than the Panama Canal and nearly 10 times larger than that of the Suez Canal!”(d)

It seems that all of Plato’s numbers, or at least all the larger ones, appear to be exaggerations and in my opinion, should be reduced by a common factor to bring them in line with credibility. I have elaborated more fully on this in Joining the Dots.

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20200709181313/http://www.atlantisbolivia.org/atlantisstade.htm

(b) https://web.archive.org/web/20180728113519/http://www.atlantisbolivia.org/ulfrichterstade.htm

(d) (99+) Atlantis and Egypt. In search of the egyptian version of the myth (academia.edu) *

(e) Ancient Units and Earth-Measure – Graham Hancock Official Website

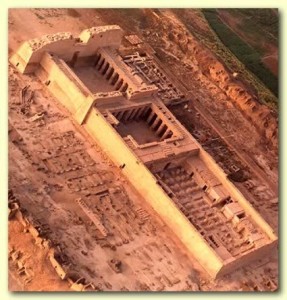

Medinet Habu

Medinet Habu is the site of the imposing mortuary temple of Ramses III at  Thebes, which is situated on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor. Adorning its walls are graphic images of the pharaoh’s victory over the ‘Sea Peoples’. A number of Atlantologists, who subscribe to the idea that these vanquished warriors were Atlanteans, have seen these carvings as firm evidence for the existence of Atlantis.

Thebes, which is situated on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor. Adorning its walls are graphic images of the pharaoh’s victory over the ‘Sea Peoples’. A number of Atlantologists, who subscribe to the idea that these vanquished warriors were Atlanteans, have seen these carvings as firm evidence for the existence of Atlantis.

Jürgen Spanuth is probably the best-known exponent of this theory in which he refers to them as ‘North Sea Peoples’. He supports his view with images from Medinet Habu depicting some of the invaders with horned helmets similar to that to that generally believed to have been used by of the Vikings. However, the Vikings did not use horned helmets(a) and those shown by Spanuth were in fact for ceremonial purposwes, showing no signs of any combat damage. Apart from that, I suggest that it is highly improbable that headgear failed to evolve between the time of Medinet Habu and that of the Vikings. However, there is evidence that horned helmets were used by Bronze Age warriors from both Sardinia and Corsica.

More recently the idea of identifying the Sea Peoples with the Atlanteans has been adopted by two other German investigators, Jürgen Hepke and Rainer Kühne.

Bibliographies of Atlantean Studies *

Bibliographies of Atlantean Studies are to be found in most books on the subject and on a number of internet sites. Understandably, these compilations are usually a reflection of the various authors’ theories and prejudices.

French

Arguably the best known Atlantis related bibliography was published in 1923 by Jean Gattefossé & Cladius Roux. It is reputed to contain 1,700 titles.

Bibliographie de I’Atlantide et des Questions connexes[0313].

Another French website with an extensive bibliography relating to mythology is:

http://racines.traditions.free.fr/bibliogr.pdf

English

Atlantis: A Select Bibliography (navy.mil) (reinstated) *

German

Jürgen Spanuth’s Atlantis of the North[015] (German & English)

Thorwald C. Franke offers an extensive list of German language titles at

https://www.atlantis-scout.de/Kommentierte%20Atlantis-Bibliographie.pdf [currently being reconstructed]

Franke has also drawn up a list of what he considers to be the best introductory titles on the subject of Atlantis in both German and English.

https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_introduction.htm

https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_einfuehrung.htm

Rainer Kühne has published an impressive list of references to Atlantis in the scientific literature.

Parte II: Israel fue La Atlántida. Los errores geográficos Platón. Historia (archive.org)

Italian

http://www.galileoparma.it/Bibliografia%20atla.html

Portuguese

A Portuguese bibliography has been compiled by Manuel J.Gandra

Mixed

Nikolai Zhirov’s Atlantis[458] has an extensive bibliography referring to works in English, Russian and other European languages.

Henry M. Eichner in his Atlantean Chronicles[287] offers a selection of titles in a dozen languages.

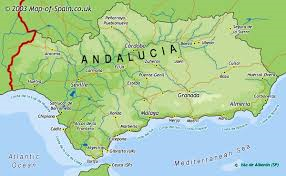

Andalusia *

Andalusia is the second largest of the seventeen autonomous communities of Spain. It is situated in the south of the country with Seville as its capital, which was earlier known as Spal when occupied by the Phoenicians.

However, there is now evidence that near the town of Orce the remains of the earliest hominids to reach Europe have been discovered. These remains have now been dated to 1.6 million years ago according to a November 2023 article on the BBC website(g).

Andalusia is thought to take its name from the Arabic al-andalus – the land of the  Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Vandals. Joaquin Vallvé Bermejo (1929-2011) was a Spanish historian and Arabist, who wrote; “Arabic texts offering the first mentions of the island of Al-Andalus and the sea of al-Andalus become extraordinarily clear if we substitute these expressions with ‘Atlantis’ or ‘Atlantic’.”[1341]

Andalusia has been identified by a number of investigators as the home of Atlantis. It appears that the earliest proponents of this idea were José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar and Johannes van Gorp in the 17th century. This view was echoed in the 19th century by the historian Francisco Fernández y Gonzáles and subsequently by his son Juan Fernandez Amador de los Rios in 1919. A decade later Mrs E. M. Whishaw published [053] the results of her extensive investigations in the region, particularly in and around Seville. In 1984, Katherine Folliot endorsed this Andalusian location for Atlantis in her book, Atlantis Revisited [054].

Stavros Papamarinopoulos has added his authoritative voice to the claim for an Andalusian Atlantis in a series of six papers(a) presented to a 2010 International Geological Congress in Patras, Greece. He argues that the Andalusian Plain matches the Plain of Atlantis but Plato clearly describes a plain that was 3,000 stadia long and 2,000 stadia wide and even if the unit of measurement was different, the ratio of length to breadth does not match the Andalusian Plain. Furthermore, Plato describes the mountains to the north of the Plain of Atlantis as being “more numerous, higher and more beautiful” than all others. The Sierra Morena to the north of Andalusia does not fit this description. The Sierra Nevada to the south is rather more impressive, but in that region, the most magnificent is the Atlas Mountains of North Africa. As well as that Plato clearly states (Critias 118b) that the Plain of Atlantis faced south while the Andalusian Plain faces west!

During the same period, the German, Adolf Schulten who also spent many years excavating in the area, was also convinced that evidence for Atlantis was to be found in Andalusia. He identified Atlantis with the legendary Tartessos[055].

Dr Rainer W. Kuhne supports the idea that the invasion of the ‘Sea Peoples’ was linked to the war with Atlantis(f), recorded by the Egyptians and he locates Atlantis in Andalusian southern Spain, placing its capital in the valley of the Guadalquivir, south of Seville. In 2003, Werner Wickboldt, a German teacher, declared that he had examined satellite photos of this region and detected structures that very closely resemble those described by Plato in Atlantis. In June 2004, AntiquityVol. 78 No. 300 published an article(b) by Dr Kuhne highlighting Wickboldt’s interpretation of the satellite photos of the area. This article was widely quoted throughout the world’s press. Their chosen site, the Doñana Marshes were linked with Atlantis over 400 years ago by José Pellicer. Kühne also offers additional information on the background to the excavation(e).

However, excavations on the ground revealed that the features identified by Wickboldt were smaller than anticipated and were from the Muslim Period. Local archaeologists have been working on the site for years until renowned self-publicist Richard Freund arrived on the scene, and spent less than a week there, but subsequently ‘allowed’ the media to describe him as leading the excavations.

Although most attention has been focused on the western end of the region, a 2015 theory(d) from Sandra Fernandez places Atlantis in the eastern province of Almeria.

Georgeos Diaz-Montexano has pointed out that Arab commentators referred to Andalus (Andalusia) north of Morocco as being home to a city covered with golden brass.

Quite a number of modern Spanish authors have opted for Andalusia as the home of Atlantis, such as G.C. Aethelman.

Karl Jürgen Hepke has an interesting website(c) where he voices his support for the idea of two Atlantises (see Lewis Spence) one in the Atlantic and the other in Andalusia.

(a) https://www.researchgate.net/search?q=ATLANTIS%20IN%20SPAIN%20I

(b) See Archive 3135

(c) http://web.archive.org/web/20191227133950/http://www.tolos.de/santorin.e.html

(d) https://atlantesdehoy.wordpress.com/2015/08/06/hola-mundo/

(e) The Archaeological Search for Tartessos-Tarshish-Atlantis – Mysteria3000 (archive.org)

(f) Lehrstuhl für theoretische Physik II (archive.org) *

(g) https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20231114-orce-spain-the-site-of-europes-earliest-settlers

German Atlantology

German Atlantologists have made a considerable contribution to their subject over the past century. In fact, outside the English speaking world the Germans can arguably claim to have contributed most to scientific Atlantology. I think that there is sufficient material to justify a book on German Atlantology on its own. The extent of their influence can be gauged by entering ‘German’ in the Atlantipedia search box.

A recent newsletter from Thorwald C. Franke highlighted the work of German researchers, particularly in the early part of the 20th century. Surprisingly, he did not mention more recent German publications including his own(a) valuable contributions. In 2016 Franke published Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis[1255] (Critical history of opinions and hypotheses about Plato’s Atlantis), which contains a review of virtually every Atlantis theorist from antiquity until the 20th century. Unfortunately, this 593-page tome is not available in English leaving German readers to be envied for having such a valuable research tool available to them. A summary of his book is available in English(b).

*So it is not without good reason that Franke recently urged serious Atlantis researchers to learn German as it provides access to a lot of valuable research.*

(a) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlanveroeff_engl.htm

(b) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-geschichte-hypothesen.htm

*Also See: Aschenbrenner, Beier, Bischoff, L. Borchardt, P. Borchardt, Christ, Hausmann, Hofmann, Horn,

Hübner, Huf, Jessen, Kühne, Muck, Richter, Schoppe, Schulten, Spanuth and Tributsch.*

Tarshish *

Tarshish is a city referred to about a dozen times in the Bible and has been widely accepted as another version of Tartessos. Josephus, the Jewish historian who wrote during the 1st century AD, was confident that it referred to Tarsus in Cilicia, Turkey, the birthplace of St. Paul. The Septuagint Bible uses Karkendonos where it refers to Tarshish in Isaiah 23:1, which was the Greek form of the name for North African Carthage. This could imply that the founders of Carthage and Tarsus were the same. We know that Carthage was founded by Tyrians and we also know that Cilix, a Tyrian, gave his name to Cilicia when he settled it. Andis Kaulins has claimed that Carthage was possibly built on the remains of Tartessos (i)!

Immanuel Velikovsky was of the opinion that “Tarshish was the name employed by the writers of the Old Testament to designate Crete as a whole, or its chief city Knossos.” as explained in a paper by his former associate Jan Sammer(m).

In 2008, Rainer Kühne published a paper titled Tartessos-Tarshish was the model for Plato’s Atlantis in which he identifies Tartessos as Tharshish, locates it in the Donana Marshes of southern Spain and suggests that it lasted from the tenth to the sixth centuries BC(p).

Utica was a Phoenician port city on the northern coast of what is now Tunisia. It no longer exists and its site is now some miles inland because of silting. It is also one of a number of suggested locations for Tarshish(f).

Tarshish/Tartessos is thought by many others to be alternative names for Atlantis. There is a consensus that it was a coastal city in Southern Spain, near modern Cadiz. Despite the efforts of many, its location is still unknown, which can probably be explained by the fact that the coastline has altered considerably over time. Adolf Schulten, who was convinced that Tartessos was Atlantis, spent many years searching, unsuccessfully, for Tarshish in Andalusia. Louis Millette is a modern writer who supports this identification but has offered little by way of evidence.

On March 20, 2011, The Jerusalem Post reported(s) that according to filmmaker Simcha Jacobvici, “it is generally acknowledged that the Biblical Tarshish is what the historians call Tartessos, which was in southern Spain. In the Tanach, Tarshish is a great city with a huge navy, with silver and gold. Jonah sails towards Tarshish. Solomon has naval expeditions with Tarshish. Tarshish disappears from the Biblical record. Tartessos disappears from the historical record.” Says Jacobovici, “Tarshish is Atlantis itself.”

In 1927, Edwin Björkman devoted a third of his book, Search for Atlantis [181] to a discussion of Tarshish and its possible connection with Atlantis.

Other locations have been suggested, such as Tharros in Sardinia, Troy and even Malta where Tarxien may be considered an echo of Tarshish. Tharros sometimes referred to as a ‘second Carthage’ had its port located as recently as 2008(d). The suggestion that Tharros was Tarshish was based on their similar-sounding names and the reference to Tarshish in the Phoenician inscription on the ‘Nora Stone’ discovered at Nora on the south coast of Sardinia in 1773.

The Brit-Am organisation, which seeks to identify the ten lost tribes of Israel has published an extensive series of papers about Tarshish(n). Responding to a question about Atlantis and Tarshish they wrote – “Atlantis does seem to have existed and does appear to have been somewhere in the Atlantic coastal area. Tarshish is a good candidate or at the least would have had some contact with Atlantis.”(o)

Quite a variety of locations have been offered as the site of Tarshish(f)(k).

Aaron Arrowsmith (1750-1832), a British cartographer and geographer was of the view that “Tartessus was a territory established by adventurous traders who settled in the Iberian peninsula after moving from the ancient city of Tarsus in Asia Minor (modern Turkey).” [1761]

It is accepted that biblical silver was sourced from ‘Tarshish’, initially assumed to be Tartessos in Spain. Recent studies employing lead isotope tests, when applied to Phoenician silver hoards(g) revealed that both Spain and Sardinia were possible sources. However, it might be argued that the Nora Stone may give Sardinia a somewhat stronger claim.

A contribution to a historum.com forum offers additional support for the idea of a Sardinian Tarshish(r).

A more radical idea was put forward in 2012 by the Spanish researcher, José Angel Hernández, who proposed that the Tarshish of the Bible was to be found in the coastal region of the Indus Valley and that Tartessos was a colony of the Indus city of Lhotal and had been situated on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar!(a)(b) This view is apparently supported by biblical references (1 Kings 9:26, 22:48; 2 Chr. 9:21) that note that the ‘ships of Tarshish’ sailed from Ezion-Geber on the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba!

Jim Allen, who has been the leading supporter for decades of the idea of Atlantis being situated in the northern Andes, has also proposed that Tarshish had been a South American city. “The more probable site of Tarshish however lies on an island at the entrance to the Pilcomayo River opposite Asuncion, since satellite photos show that at this point the Pilcomayo forks into two arms exactly as per the ancient text, creating an island between the arms of the river. Moreover also in accordance with the ancient text, the river discharges into a broad bay – the Bay of Asuncion and this part of the Paraguay River also comprises shallows and sandbanks.”(l) This demonstrates that Allen saw Atlantis and Tarshish as separate entities.

However, if Tarshish was another name for Atlantis and according to the bible it existed at the time of Solomon, circa 1000 BC, we are confronted with a contradiction of Plato’s 9,000 years elapsing since the destruction of Atlantis and the visit of Solon to Sais. King Jehoshaphat reigned around 860 BC and planned to send a fleet to Tarshish, just 200 years before Solon, so the likelihood of Tarshish being Atlantis is a rather remote possibility.

A recent suggestion by a Dutch commentator, Leon Elshout, places the biblical Tarshish in Britain(h) an idea supported by a Christadelphian website(j).

(a) https://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/mito-y-religion/

(b) https://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/arqueologia-e-historia/

(c) https://www.academia.edu/5812547/Tharros_the_megalithic_city

(d) discovered the Phoenician city of Tharros, in Sardinia (archive.org)

(f) https://www.notjustanotherbook.com/tarshish.htm

(h) (8) Tarshish as Great Britain and the paradox with Atlantis – Rood Goud van Parvaïm (archive.org) *

(i) Pillars of Heracles – Alternative Location (archive.org)

(j) Incredible Archaeological Find Proves Tarshish Is Britain! (archive.org)

(k) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarshish#Sardinia

(l) http://www.geocities.ws/myessays/LocationofTarshish.htm

(m) https://www.varchive.org/nldag/tarshish.htm

(n) https://www.britam.org/Questions/QuesTarshish.html

(o) Scroll down to Question 2 in (n)

(p) https://vixra.org/pdf/1103.0040v1.pdf

(q) tarshishtarsus (bibleorigins.net)

(r) https://historum.com/t/the-nuragic-civilization-of-sardinia-was-it-tarshish.127443/

(s) https://www.jpost.com/jewish-world/jewish-news/the-deepest-jewish-encampment