R. G. Bury

Atlanticus

Atlanticus is the word used by Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa to describe Atlantis. Thomas Taylor in his celebrated translation of Plato’s works, has subtitled Critias as Atlanticus. In the 20th century, The Critias Atlanticus was published, being a compilation(a) of seven translations of Plato’s Critias that includes the work of Thomas Taylor, Benjamin Jowett, Henry Davis, R. G. Bury, Lewis Spence, W.R.M. Lamb, John Alexander Stewart.

Tuttle, Robert J.

Robert J. Tuttle (1935- ) is an American nuclear engineer and the author of The Fourth Source: Effects of  Natural Nuclear Reactors[1148], which is a ground-breaking review of “how the effects of nature’s own nuclear reactors have shaped the Earth, the Solar System, the Universe, and the history of life as we know it.”

Natural Nuclear Reactors[1148], which is a ground-breaking review of “how the effects of nature’s own nuclear reactors have shaped the Earth, the Solar System, the Universe, and the history of life as we know it.”

This large volume (580 pages) challenges many accepted theories, such as glaciation, evolution, and mass extinctions and offers new ideas that will undoubtedly raise eyebrows(a).*The first 25 pages can be downloaded as a free pdf file.*

Surprisingly, Tuttle also tackles the question of Atlantis (p.301) suggesting the possibility that when sea levels were lower, the Balearic Islands in the Western Mediterranean were more extensive and possibly the home of Atlantis. He takes issue with Bury and Lee who refer to the ‘Atlantic Ocean’, which he claims should read as the ‘Sea of Atlantis’ and locates the ‘Pillars of Herakles’ somewhere between Tunisia, Sicily and the toe of Italy.

*(a) https://www.universal-publishers.com/book.php?method=ISBN&book=1612330770*

Tyrrhenian Sea

>The Tyrrhenian Sea according to Massimo Pittau was named after the Sardinian Nuragics, since in ancient Greek ‘Tyrrenoi’ means ‘builders of towers’. As noted elsewhere, Sardinia was an important part of the Atlantean domain.<

Plato clearly states that Atlantis controlled Europe as far as Tyrrhenia (Critias 114c), which implies that they dominated the southern half of the Italian peninsula. The Sea is surrounded by the islands of Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily and the Lipari Islands as well as continental Europe in the form of the Italian mainland. Not only does it contain islands with an adjacent continent (see Timaeus 24e). It is also accessed through the straits of Messina and Sicily, both of which have been identified as locations for the Pillars of Heracles before Eratosthenes applied that appellation to the region of Gibraltar.

Timaeus 24e-25a as translated by Bury reads “there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travellers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the continent over against them which encompasses that veritable ocean (pontos=sea). For all that we have here, lying within the mouth of which we speak, is evidently a haven having a narrow entrance; but that yonder is a real ocean (pelagos=sea), and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent.” Similarly, Lee and Jowett have  misleadingly translated both pontos and pelagos as ‘ocean’, while the earliest English translation by Thomas Taylor correctly renders them as ‘sea’. Modern translators such as Joseph Warren Wells and a Greek commentator George Sarantitis are both quite happy to agree with Taylor’s translation. However, Peter Kalkavage translates pontos as ‘sea’ but pelagos as ‘ocean’!

misleadingly translated both pontos and pelagos as ‘ocean’, while the earliest English translation by Thomas Taylor correctly renders them as ‘sea’. Modern translators such as Joseph Warren Wells and a Greek commentator George Sarantitis are both quite happy to agree with Taylor’s translation. However, Peter Kalkavage translates pontos as ‘sea’ but pelagos as ‘ocean’!

For me, there is a very strong case to be made for identifying the Tyrrhenian Sea as the ‘sea’ referred to by Plato in the passage quoted above. However, it was probably F.Butavand, in 1925, who first proposed the Tyrrhenian as the sea described by Plato in his La Veritable Histoire de L’Atlantide[205] .

Pushing the boat out a little further, I note that Rome is situated in Central Italy and by tradition was founded by the twins Romulus and Remus!

A 1700 map of the Tyrrhenian Sea is available online.

‘Tyrrhenia’ is sometimes used as a geological term to describe a sunken landmass in the Western Mediterranean Basin(b)(c).

(a) (link broken) *

The Critias Atlanticus

The Critias Atlanticus is a compilation(a) of seven translations of Plato’s Critias that includes the work of Thomas Taylor, Benjamin Jowett, Henry Davis, R. G. Bury, Lewis Spence, W.R.M. Lamb, and John Alexander Stewart.

(a) https://www.hiddenmysteries.com/xcart/Critias-Atlanticus.html

Susemihl, Franz

Franz Susemihl (1826-1901) was a professor of classical philology at Greifswald University and later became rector there. He was renowned in academic circles for his translations of the works of Plato and Aristotle. His remarks on the Atlantis commentators of his day are as relevant today as over a century ago when he said “The catalogue of statements about Atlantis is a fairly good aid for the study of human madness.” The accuracy of his statement is borne out by the swollen ranks of today’s ‘lunatic fringe’ who claim inspiration from psychics, extraterrestrials or who insist that Atlantis was powered by crystals and possessed flying machines. The publication of such nonsense has continually undermined the credibility of serious Atlantology.

Franz Susemihl (1826-1901) was a professor of classical philology at Greifswald University and later became rector there. He was renowned in academic circles for his translations of the works of Plato and Aristotle. His remarks on the Atlantis commentators of his day are as relevant today as over a century ago when he said “The catalogue of statements about Atlantis is a fairly good aid for the study of human madness.” The accuracy of his statement is borne out by the swollen ranks of today’s ‘lunatic fringe’ who claim inspiration from psychics, extraterrestrials or who insist that Atlantis was powered by crystals and possessed flying machines. The publication of such nonsense has continually undermined the credibility of serious Atlantology.

Susemihl’s German translation of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias is available online.(a)(b). Thorwald C. Franke has also included Susemihl’s translation along with that of Müller, Bury and Jowett and the Greek text of John Burnet[1492], all in a parallel format(c).

It should be noted that Susemihl was an Atlantis sceptic.

(a) TIMAIOS (archive.org) *

(b) KRITIAS (archive.org) *

(c) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-timaeus-critias-synopsis.htm

Meizon

Meizon is given the sole meaning of ‘greater’ in the respected Greek Lexicon of Liddell & Scott. Furthermore, in Bury’s translation of sections 20e -26a of Timaeus there are eleven instances of Plato using megas (great) meizon (greater) or megistos (greatest). In all cases, great or greatest is employed except just one, 24e, which uses the comparative meizon, which Bury translated as ‘larger’! J.Warren Wells concluded that Bury’s translation in this single instance is inconsistent with his other treatments of the word and it does not fit comfortably with the context[787.85]. This inconsistency is difficult to accept, so although meizon can have a secondary meaning of ‘larger’ it is quite reasonable to assume that the primary meaning of ‘greater’ was intended.

Jürgen Spanuth addressed this problem in Atlantis-The Mystery Unravelled [017.109] noting that “In other parts of the Atlantis report misunderstandings easily arose. Plato asserts that Atlantis was ‘larger’, ‘more extensive’ (meizon),than Libya and Asia Minor. The Greek word ‘meizon’ can mean both ‘larger in size’ and ‘more powerful.’ As the size of the Atlantean kingdom is given between two hundred and three hundred miles, whereas Asia Minor is considerably bigger, in this context the word ‘meizon’ should be translated not by ‘larger in size’ but by ‘more powerful’, which corresponds much better to the actual facts.”

In 2006, on a now-defunct website of his, Wells noted that “Greater can mean larger, but this meaning is by no means the only possible meaning here; his overall usage of the word may show he meant greater in some other way.”

It is also worth considering that Alexander the Great, (Aléxandros ho Mégas) was so-called, not because of his physical size, apparently, he was short of stature, but because he was a powerful leader.

The word has entered Atlantis debates in relation to its use in Timaeus 24e ’, where Plato describes Atlantis as ‘greater’ than Libya and Asia together and until recently has been most frequently interpreted to mean greater ‘in size’, an idea that I previously endorsed. However, some researchers have suggested that he intended to mean greater ‘in power’.

Other commentators do not seem to be fully aware that ‘Libya’ and ‘Asia’ had completely different meanings at the time of Plato. ‘Libya’ referred to part or all of North Africa, west of Egypt, while ‘Asia’ was sometimes applied to Lydia, a small kingdom in what is today Turkey. Incidentally, Plato’s statement also demonstrates that Atlantis could not have existed in either of these territories as ‘a part cannot be greater than the whole.’

A more radical, but less credible, interpretation of Plato’s use of ‘meizon’ came from the historian P.B.S. Andrews suggested that the quotation has been the result of a misreading of Solon’s notes. He maintained that the text should be read as ’midway between Libya and Asia’ since in the original Greek there is only a difference on one letter between the words for midway (meson) and larger than (meizon). This suggestion was supported by the classical scholar J.V. Luce and more recently on Marilyn Luongo‘s website(a), which is now closed.

Luongo attempted to link Mesopotamia with Atlantis, beginning with locating the ‘Pillars of Heracles‘ at the Strait of Hormuz and then using the highly controversial interpretation of ‘meizon‘ meaning ‘between’ rather than ‘greater’ she proceeded to argue that Mesopotamia is ‘between’ Asia and Libya and therefore is the home of Atlantis! She cited a paper by Andreea Haktanir to justify this interpretation of meizon(a).

This interpretation is quite interesting, particularly if the Lydian explanation of ‘Asia’ mentioned above is correct. Viewed from either Athens or Egypt we find that Crete is located ‘midway’ between Lydia and Libya.

Jacques R. Pauwels also supported Andrews’ controversial interpretation of Plato’s text (Tim.24d-e) in his 2010 book Beneath the Dust of Time [1656]. Therefore, he believes that the text should have described Atlantis as being between Libya and Asia rather than greater than Libya and Asia combined, arguably pointing to the Minoan Hypothesis.

As there are hundreds of islands ‘between’ Libya and Asia in the Aegean, this interpretation is very imprecise and useless as a geographical pointer.

In 2021, Diego Ratti, proposed in his new book Atletenu [1821], an Egyptian location for Atlantis, centred on the Hyksos capital, Avaris. In that context, he found it expedient to interpret ‘meizon’ in Tim. 24e & Crit.108e as meaning between Libya and Asia, which Avaris clearly is. I pressed Ratti on this interpretation and, after further study, he responded with a more detailed explanation for his conclusion(d). This is best read in conjunction with the book.

Some years ago, the late R. Cedric Leonard offered the following contribution to the meizon debate:

In Plato’s time (4th century B.C.) he would have written in large (all-capitals), continuous (no spaces between words), Athenian characters. The old Greek word meson would look like MESON in the Athenian script of Plato’s time. But mezon would look like MEION – the ancient Z closely resembled our modern capital letter I – the difference between the S and Z in the large Athenian script is obvious. (The Greek Z resembling our Roman Z is modern and does not apply to the older Attic scripts.)

But even in the later minuscule script the s and z in no wise resemble each other. A minuscule z (zeta) looks like ? while a medial s (sigma) looks like ? (absolutely nothing alike). The final backbreaker is that Plato included the same comparison in his Critias (108), in which his copyists would have to have made an identical mistake in that work as well. The odds are against the same identical mistake occuring in two separate works.(e) (see link for actual characters)

In relation to all this, Felice Vinci has explained that ancient mariners measured territory by the length of its coastal perimeter, a method that was in use up to the time of Columbus. This would imply that the island of Atlantis was relatively modest in extent – I would speculate somewhere between the size of Cyprus and Sardinia. An area of such an extent has never been known to have been destroyed by an earthquake.

Until the 21st century, it was thought by many that meizon must have referred to the physical size of Atlantis rather than its military power. However, having read a paper[750.173] delivered by Thorwald C. Franke at the 2008 Atlantis Conference, I was persuaded otherwise. His explanation is that “for Egyptians, the world of their ‘traditional’ enemies was divided in two: To the west, there were the Libyans, to the east there were the Asians. If an Egyptian scribe wanted to say, that an enemy was more dangerous than the ‘usual’ enemies, which was the case with the Sea Peoples’ invasion, then he would have most probably said, that this enemy was ‘more powerful than Libya and Asia put together’”.

This is a far more elegant and credible explanation than any reference to physical size, which forced researchers to seek lost continental-sized land masses and apparently justified the negativity of sceptics. Furthermore, it reinforces the Egyptian origin of the Atlantis story, demolishing any claim that Plato concocted the whole tale. If it had been invented by Plato he would probably have compared Atlantis to enemy territories nearer to home, such as the Persians.

This interpretation of meizon has now been ‘adopted’ by Frank Joseph in The Destruction of Atlantis[102.82], but without giving any due credit to Franke(b). No surprise there.!

(b) https://lost-origins.com/atlantis-no-lost-continent/ (offline Jan. 2018) See: http://web.archive.org/web/20210625013615/https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-2349/

(c) https://web.archive.org/web/20070212101539/https://greekatlantis.com/

(d) More on Atlantis between Asia and Libya (archive.org)

(e) https://web.archive.org/web/20170113130726/http://www.atlantisquest.com/Plato.html

Bury, Rev. Robert Gregg

Rev. Robert Gregg Bury (1869-1951) was born in Clontibret, Co. Monaghan, Ireland and died in Cambridge, England. He was a renowned translator of many of Plato’s works including Critias and Timaeus[204], which gave the world the first direct references to Atlantis. His translation(c)* of the Atlantean texts is considered by some to be superior to the more commonly quoted Jowett translation and is to be found on the Internet(a) and as an appendix to the Galanopoulos & Bacon book, Atlantis: The Truth behind the Legend.

A useful concordance of the Atlantis sections of the Dialogues is available in hard copy and as an inexpensive download(b).

(a) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_timaeus_critias.htm

(b) https://www.lulu.de/content/731731 (link broken July 2018)

(c) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_timaeus_critias.htm#bury *

Franke, Thorwald C.

Thorwald C. Franke was born in 1971 in Konstanz in southwest Germany. He studied computer science at the University of Karlsruhe and now works as a software developer. Since 1999 he has been promoting the idea of Atlantis having been located in Sicily. He has written a paper, which makes the case for identifying Atlas with king Italos of the Sicels, who was one of the first tribes to inhabit Sicily and gave their name to the island.

In October 2010, Franke announced that a part of his theory has some elements in it that require further research(f).

He believes that the war with the Atlanteans was recorded by the Egyptians as the conflict with the Sea Peoples of whom the Sicilians are generally accepted to have been part.

Franke has a well-presented website(a), in English and German, where he cogently outlines his views. He has also written a lengthy, 23-page paper on the need for a classification of Atlantis theories. Even though this item is in German, English readers may find it quite interesting using their browser’s translator. Franke has also compiled an extensive list of Atlantis-related websites(d) that he expanded further in a new format in October 2011.

His paper for the 2nd Atlantis Conference in Athens in 2008 is available on the Internet(c) in which he expanded on his Sicilian location for Atlantis.

Franke has also published a book, in German[300] that focussed on Herodotus’ contribution to the Atlantis question(p). In the same paper, he dealt with the true meaning of the word ‘meizon‘ in Timaeus 24e which tells us that Atlantis was ‘greater’ than Asia and Libya combined, which he clarified as actually referring to their combined power rather than size. However, Franke proposed that the Egyptian word ‘wr’, whose primary meaning is ‘big’ and is sometimes used in a metaphorical sense, may have influenced the wording of the Greek text

Franke has also published a book, in German[300] that focussed on Herodotus’ contribution to the Atlantis question(p). In the same paper, he dealt with the true meaning of the word ‘meizon‘ in Timaeus 24e which tells us that Atlantis was ‘greater’ than Asia and Libya combined, which he clarified as actually referring to their combined power rather than size. However, Franke proposed that the Egyptian word ‘wr’, whose primary meaning is ‘big’ and is sometimes used in a metaphorical sense, may have influenced the wording of the Greek text

Then in a more recent (2010) book[706] regarding Aristotle and Atlantis, he disputes the generally perceived view that Aristotle did not accept the existence of Atlantis. He builds his case on an 1816 misinterpretation by a French mathematician, Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre, of a 1587 commentary on Strabo’s Geographica by Isaac Casaubon. Combined with other evidence he has presented a case that removes the only prominent classical writer alleged to have dismissed the existence of Atlantis. In late 2012 Franke published an English translation with the title of Aristotle and Atlantis[880]. Franke’s views regarding Aristotle have been well received and his book is frequently cited, most recently by Dhani Irwanto in his Atlantis: The Lost City is in the Java Sea[1093.110].

Franke has now augmented his book on Aristotle with a YouTube video in English(l) and German(m). This important book can now be read on the Researchgate website.(ae)

2012 also saw the publication, by Franke, of the first English translation of Gunnar Rudberg’s 1917 monograph Atlantis och Syrakusai, now Atlantis and Syracuse[881]. This is a welcome addition to Atlantis literature in English. Students of the Atlantis mystery owe a debt of gratitude to Herr Franke.

In 2006, Franke published a paper outlining Wilhelm Brandenstein’s contribution to Atlantology which in 2013 he published in English(g). This was followed by a translation(h) of his overview of the work of Massimo Pallattino, who had adopted some of Brandenstein’s approaches to the Atlantis question.

On the 30th of May 2013, Franke announced(i) that his Atlantis Newsletter, which until now was only available in German, in future will also be published in English. Today he discusses the antics of extremist Atlantis sceptics and the abuse of Wikipedia. I encourage everyone to register and congratulate Thorwald on this development.

There is also a video clip available of Franke showing his library of Atlantis-related books(e). 2017 has seen Franke produce a number of 30-minute videos, which readers will find informative. They are available in both German and English, (Just Google Plato’s Atlantis – Thorwald C. Franke – YouTube).

Franke has now (July 2013) revamped his website (https://www.atlantis-scout.de/)

More recently, July 2016 saw the publication, in German, of Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis[1255] (Critical history of the hypotheses on Plato’s Atlantis). This tome of nearly 600 pages will undoubtedly be a valuable addition to any serious researcher’s library. There is a promotional video, in German, to go with it(j). Hopefully, an English translation of the book will follow. However, Franke does provide an English summary of the book(af). In June 2021, Franke announced the publication of the second edition of this remarkable book, but again, in German only. It is now in two volumes, totalling over 800 pages, which include hundreds of new references(y). Two publications in one week is a record to be proud of.

In June 2018, Franke published a YouTube video in English(r) and German(s) highlighting how Plato’s 9,000 years have been alternatively accepted and then rejected many times over since the time of Plato. Franke proposes that the 9,000 years recorded by Plato were comparable with the accepted age of Egypt in his day, at 11,00 years. However, archaeology has demonstrated that Egypt was only 3,000 years old or less when Plato was alive, suggesting that the 9,000 should be reduced by a comparable amount to arrive at the real-time of Atlantis.

In his Newsletter No.90, Franke has highlighted that a small German right-wing group, ‘Pro Deutschland’, has cited on their website the ‘superior civilisation’ of Atlantis in support of their extremist views.

Franke’s Newsletter No. 103 has now provided us with five parallel versions of the Atlantis texts(n), Two English; Jowett & Bury and Two German; Susemihl & Müller as well as a Greek text from the Scottish classicist John Burnet (1863 – 1928)[1492].

Franke’s Newsletter No.104 offers an overview of the difficulties involved in accepting Plato’s writings too literally(o). He gives particular attention to the 9,000 years claimed to have elapsed between the Atlantean War and Solon’s visit to Egypt.

In November 2017, Franke published an uncompromising critique(q) of Stephen P. Kershaw’s recent book, A Brief History of Atlantis[1410].

Franke has now published two new videos(t), in both German and English, in which he reviews a number of Atlantis-related books, both supportive and sceptical. He does so in his usual balanced manner and also exhorts students of Atlantology to learn German to have access to important works only available in that language.

The difficulty of independent researchers getting their work published in academic journals was highlighted by Franke some time ago(a). However, he has had some academic recognition(a) and has modified his view on the function of the academic press vis-á-vis independent writers(a).

>>An interesting paper by Franke entitled The Dark Side of Atlantis Scepticism(aq) was published in 2021, which outlines how scepticism has been used to promote such diverse subjects as false religious and political dogmas.<<

In June 2021, Franke announced the publication of his latest book(x). Platonische Mythen (Platonic Myths)[1858], currently in German only. In May 2022 a favourable review, also in German, of Franke’s book was published on the atlantisforschung.de website(ag). I have archived an English translation in atlantipedia.ie(ah).

The following month, Franke published Newsletter No.175 in which he accuses the Bryn Mawr Classical Review (BMCR) of scientific bias and inconsistency(z). The full Newsletter should be read but in particular his conclusions below.

“Let us sum up what we have: BMCR claims to accept no self-published books, but it did review such a book [mine-AO’C]. BMCR claims that it accepts only peer-reviewed books, but besides the question, of what this exactly means, they do indeed review books that were not peer-reviewed. BMCR claims to accept translations but did not accept the translation of Gunnar Rudberg [Franke’s]. BMCR claims to review bad Atlantis books of a certain intelligence in order to debunk them, but at the same time, they avoided a review of a bad book by an Atlantis sceptical Oxford scholar. They claim to treat every author with respect but failed to do so in my case, and not only once. And the same scholar who admits that his scientific view was impacted (!) by one of my books writes BMCR reviews about other Atlantis books, but my books are not reviewed. Long story short: BMCR acts in an arbitrary way and damages its credibility. They screwed up everything that can be screwed up. And it was not me who lead them up the garden path. They did that all by themselves.”

In Franke’s Newsletter No.158 published in early 2021, he reviewed a lecture, previously unknown to him, given by Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, in Bologna, a few years ago(aa) during which he apparently misrepresented Franke’s Atlantis theories. Shortly afterward Nesselrath issued a rather intemperate reply to Franke’s criticisms.(ab) A further document(ac) from Franke detailed his continuing annoyance with what he perceives as ‘a breach of trust’ on the part of Nesselrath. Now in August 2021, Nesselrath has reignited matters again with a further assault on Franke’s views(ad), many of which I share. In a further postscript dated 20.08.21(ab) Franke fired off a few more salvos. I think it’s time for an armistice?

However, in April 2023, Franke issued his Newsletter No. 212(ao), with the following introduction;

“Professor Heinz-Günther Nesselrath has once again written and published two PDF articles(ak)(al) to defend his Atlantis scepticism against the arguments brought up by me. One is directed against my internet article “The Dark Side of Atlantis Scepticism” from 2021, based on my book about the reception history of Plato’s Atlantis story from 2016/2021. The other one makes the attempt to undermine especially the literary arguments of Wilhelm Brandenstein, which I cultivated and will cultivate even more in my next publication.”

Franke responded with two papers(am)(an) that should be read in their entirety.

Franke’s Newsletter #193 reviews an interview with sceptic Flint Dibble(ai). He followed that in July 2022 (#194) with a critique of an article ‘Not Exactly Atlantis’ by Professor Carolina López-Ruiz that Franke identifies as over-dependent on the arguments of promoters of the ‘invention hypothesis’ particularly those of Pierre Vidal-Naquet and Diskin Clay. Franke then proceeded to offer a list of her many errors(aj).

In January 2024, Franke published his Newsletter #215(ao) where he references a 2023 Graham Hancock lecture(ap) in which “He just takes the numbers in Plato’s text literally, and on this basis he makes his conclusions and calculations. He never asks the question, not for a second, that Plato’s numbers could be wrong. Wrong in a very typical and understandable way, when looking to the historical context. Because, all the ancient Greeks were wrong about the age of Egypt (where the Atlantis story allegedly, or really, had come from). They thought, Egypt was 10,000 years old, and older. But in fact, Egypt was founded only around 3,000 BC. Therefore, if an ancient Greek text points to an event 9,000 years before its time, of which it got to know from Egypt, this means in fact a time after 3,000 BC.

Once you realize this, the whole narrative of a prehistorical Ice Age civilization melts down to nothing, and a completely different picture of the Atlantis question appears.”

In late 2025, Franke published his Newsletter No 239(ar) in which highlights that, “recently, Elon Musk presented a new alternative Internet encyclopedia “Grokipedia” which was written entirely by Artificial Intelligence. Grokipedia is thus a competitor to Wikipedia which is written by – certain – human beings.

A short review quickly reveals that Grokipedia very strongly adheres to the alleged “scholarly consensus”, i.e., this article is 100% on the side of the Atlantis sceptics, not even mentioning scholarly dissent. Grokipedia is even more on the side of the Atlantis sceptics than the corresponding Wikipedia article which allows at least glimpses into alternative opinions.”

(a) http://www.thorwalds-internetseiten.de

(c) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_sicily.htm

(d) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlanlinks.htm

(e) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5r2yDLEYfjA (link broken)

(f) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/index_engl.htm

(g) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_brandenstein_engl.htm

(h) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_pallottino_engl.htm

(i) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_newsl_archive.htm

(j) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1orj7aqdTo (link broken)

(k) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_newsl_archive.htm

(l) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=inWb6IVNWFQ (English)

(m) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qDG7a09xkZE (German)

(n) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-timaeus-critias-synopsis.htm

(o) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-historical-critical-engl.htm

(p) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/Franke_Herodotus_Atlantis2008_Proceedings.pdf

(q) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/kershaw-brief-history-atlantis-review-engl.htm

(r) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F2RlO_vhk8c

(s) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yb-24rxELnc

(u) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-academic-journals-engl.htm

(v) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-success-engl.htm

(w) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_newsl_archive.htm

(x) & (y) https://www.amazon.de/Bücher-Thorwald-C-Franke/s?rh=n:186606,p_27:Thorwald+C.+Franke

(z) The scientific bias of the BMCR review – Atlantis-Scout

(aa) Review of: Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, News from Atlantis? 2017. (atlantis-scout.de) (See first half)

(ab) Review of: Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, News from Atlantis? 2017. (atlantis-scout.de) (See last half)

(ac) Severe breach of trust by Heinz-Günther Nesselrath (atlantis-scout.de)

(af) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-geschichte-hypothesen.htm

(ag) Buchbesprechung: Thorwald C. Franke: Platonische Mythen – Atlantisforschung.de

(ah) http://web.archive.org/web/20220517001233/https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/archive-7104/

(ai) Atlantis Newsletter Archive – Atlantis-Scout

(aj) Review of: Carolina López-Ruiz, Not Exactly Atlantis – Atlantis-Scout

(ao) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_newsl_archive.htm

(ap) Graham Hancock: Beyond Ancient Apocalypse | Presentation @ Logan Hall, London – YouTube

(aq) (99+) The Dark Side of Atlantis Scepticism | Thorwald C. Franke – Academia.edu

(ar) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis_newsl_archive.htm

Müller, Hieronymus

Hieronymus (Jerome) Müller (1785-1861) was a German philologist who produced a well received German translation of Plato’s works, published in Leipzig in 1856.

Thorwald C. Franke has also included Müller’s German translation along with that of Susemihl and the English translations of Bury and Jowett, together with the Greek text of John Burnet[1492], all in a parallel format(a).

Müller is reputed to have identified Lyktonia with Atlantis.

(a) https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-timaeus-critias-synopsis.htm

Shoals of Mud

A Shoal of mud is stated by Plato (Tim.25d) to mark the location of where Atlantis ‘settled’. He described these shallows in the present tense, clearly implying that they were still a maritime hindrance even in Plato’s day.

Three of the most popular translations clearly indicate this:

….the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.

…..the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal of mud which the island created as it settled down.”

…..the sea in that area is to this day impassible to navigation, which is hindered by mud just below the surface, the remains of the sunken island.

Wikipedia has noted(h) that “during the early first century, the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo wrote about the destruction of Atlantis in his On the Eternity of the World, xxvi. 141, in a longer passage allegedly citing Aristotle’s successor Theophrastus.

‘ And the island of Atalantes [translator’s spelling; original: “????????”] which was greater than Africa and Asia, as Plato says in the Timaeus, in one day and night was overwhelmed beneath the sea in consequence of an extraordinary earthquake and inundation and suddenly disappeared, becoming sea, not indeed navigable, but full of gulfs and eddies’.”

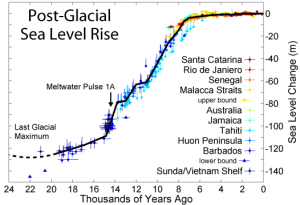

Since it is probable that Atlantis was destroyed around a thousand years or more before Solon’s Egyptian sojourn, to have continued as a hazard for such a period suggests a location that was little affected by currents or tides. The latter would seem to offer support for a Mediterranean Atlantis as that sea enjoys negligible tidal changes, as can be seen from the chart below. The darkest shade of blue indicates the areas of minimal tidal effect.

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

If Plato was correct in stating that Atlantis was submerged in a single day and that it was still close to the water’s surface in his own day, its destruction must have taken place a relatively short time before since the slowly rising sea levels would eventually have deepened the waters covering the remains of Atlantis to the point where they would not pose any danger to shipping. The triremes of Plato’s time had an estimated draught of about a metre so the shallows must have had a depth that was less than that.

The reference to mud shoals resulting from an earthquake brings to mind the possibility of liquefaction. This is perhaps what happened to the two submerged ancient cities close to modern Alexandria. Their remains lie nine metres under the surface of the Mediterranean.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Our knowledge of sea-level changes over the past two and a half millennia should enable us to roughly estimate all possible locations in the Mediterranean where the depth of water of any submerged remains would have been a metre or less in the time of Plato.

Some supporters of a Black Sea Atlantis have suggested the shallow Strait of Kerch between Crimea and Russia as the location of Plato’s ‘shoals’(e) .

The tidal map above offers two areas west of Athens and Egypt that do appear to be credible location regions, namely, (1) from the Balearic Islands, south to North Africa and (2), a more credible straddling the Strait of Sicily. This region offers additional features, making it much more compatible with Plato’s account.

By contrast, just over a hundred miles south of that Strait, lies the Gulf of Gabés, which boasts the greatest tidal range (max 8 ft) within the Mediterranean.

The Gulf of Gabes formerly known as Syrtis Minor and the larger Gulf of Sidra to the east, previously known as Syrtis Major, was greatly feared by ancient mariners and continue to be very dangerous today because of the shifting sandbanks created by tides in the area.

There are two principal ancient texts that possibly support the gulfs of Syrtis as the location of Plato’s ‘shoal’. The first is from Apollonius of Rhodes who was a 3rd-century BC librarian at Alexandria. In his Argonautica (Bk IV ii 1228-1250)(a) he unequivocally speaks of the dangerous shoals in the Gulf of Syrtis. The second source is the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 27 13-18) written three centuries later, which describes how St. Paul on his way to Rome was blown off course and feared that they would run aground on “Syrtis sands.” However, good fortune was with them and after fourteen days they landed on Malta. The Maltese claim regarding St. Paul is rivalled by that of the Croatian island of Mljet as well Argostoli on the Greek island of Cephalonia. Even more radical is the convincing evidence offered by Kenneth Humphreys to demonstrate that the Pauline story is an invention(b).

Both the Strait of Sicily and the Gulf of Gabes have been included in a number of Atlantis theories. The Strait and the Gulf were seen as part of a larger landmass that included Sicily according to Butavand, Arecchi and Sarantitis who named the Gulf of Gabes as the location of the Pillars of Heracles. Many commentators such as Frau, Rapisarda and Lilliu have designated the Strait of Sicily as the ‘Pillars’, while in the centre of the Strait we have Malta with its own Atlantis claims.

Zhirov[458.25] tried to explain away the ‘shoals’ as just pumice stone, frequently found in large quantities after volcanic eruptions. However, Plato records an earthquake, not an eruption and Zhirov did not explain how the pumice stone was still a hazard many hundreds of years after the event. Although pumice can float for years, it will eventually sink(c). It was reported that pumice rafts associated with the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa were found floating up to 20 years after that event. Zhirov’s theory does not hold water (no pun intended) apart from which, Atlantis was destroyed as a result of an earthquake. not a volcanic eruption and I think that the shoals described by Plato were more likely to have been created by liquefaction and could not have endured for centuries.

Nevertheless, a lengthy 2020 paper(d) by Ulrich Johann offers additional information about pumice and in a surprising conclusion proposes that it was pumice rafts that inspired Plato’s reference to shoals!

Andrew Collins in an effort to justify his Cuban location for Atlantis needed to find Plato’s ‘shoals of mud’ in the Atlantic and for me, in what seems to have been an act of desperation he decided that the Sargasso Sea fitted the bill [072.42]. Similarly, Emilio Spedicato in support of a Hispaniola Atlantis also opted for the Sargasso. However, neither Collins or Spedicato were the first to make this suggestion. Chedomille Mijatovich (1842-1932), a Serbian politician, economist and historian was one of the first in modern times to suggest that the Sargasso Sea may have been the maritime hazard described by Plato as a ‘shoal of mud’, which resulted from the submergence of Atlantis. However, neither explains how anyone can mistake seaweed for mud!

The late Andis Kaulins believed that Atlantis did exist and considered two possible regions for its location; the Minoan island of Thera or some part of the North Sea that was submerged at the end of the last Ice Age when the sea levels rose dramatically. Kaulins noted that part of the North Sea is known locally as ‘Wattenmeer’ or Sea of Mud’ reminiscent of Plato’s description of the region where Atlantis was submerged, after that event.

An even more absurd suggestion came from the American scholar William Arthur Heidel (1868-1941), who denied the reality of Atlantis and wrote a critical paper [0374] on the subject (republished July 2013(g)). He claimed that an expeditionary naval force sent by Darius in 515 BC under Scylax of Caryanda to explore the Indus River, eventually encountered waters too shallow for his ships, and that this was the inspiration behind Plato’s tale of unnavigable seas. Heidel further claimed that Plato’s battle between Atlantis and Athens is a distorted account of the war of invasion between the Persians and the peoples of the Indus Valley (Now Pakistan)!

(a) https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/argo/argo53.htm

(b) The Curious Yarn of Paul’s “Shipwreck” (archive.org)

(c) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170523144110.htm

(e) Index (atlantis-today.com)

(f) http://web.archive.org/web/20181208222201/https://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread61382/pg1

(g) A Suggestion concerning Plato’s Atlantis on JSTOR (archive.org)

(h) Atlantis – Wikipedia_?s=books&ie=UTF&qid=1376067567&sr=-