Richard Hennig

Netolitzky, Friedrich

Friedrich (Fritz) Netolitzky (1875-1945) was an entomologist and a professor of botany, which he taught at a number of universities. However, he also had a keen interest in the mystery of Atlantis.

However, he also had a keen interest in the mystery of Atlantis.

Atlantisforschung notes(a) “The fact that F. Netolitzky’s Atlantological work was not completely forgotten after his death is mainly due to the historical geographer Richard Hennig (1874-1951), who wrote about him and his work in several of his books – above all in Das Rätsel der Atlantis (The Puzzle of Atlantis) (first publication 1925). There (pp. 21-24 ) we learn, for example, that Netolitzky ‘s considerations about an Iberian Atlantis of the Bronze Age inspired Adolf Schulten‘s research into Atlantis and Tartessos, who, according to Hennig, described them in individual details”

Netolitzky also provided an independent interpretation of the oriharukon (orichalcum) from Plato’sAtlantis account, which he identified as an artificial modification of white gold (known as Asem in ancient Egypt).

(a) Friedrich Netolitzky – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

Pillars of Herakles

Pillars of Heracles, when Googled, will offer nearly 100,000 results, with Wikipedia and Britannica usually heading the list.

Wikipedia says “The Pillars of Hercules was the phrase that was applied in Antiquity to the promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. The northern Pillar, Calpe Mons, is the Rock of Gibraltar. A corresponding North African peak not being predominant, the identity of the southern Pillar, Abila Mons, has been disputed throughout history, with the two most likely candidates being Monte Hacho in Ceuta and Jebel Musa in Morocco.”

Britannica says “Pillars of Heracles, also called Pillars of Hercules, two promontories at the eastern end of the Strait of Gibraltar. The northern pillar is the Rock of Gibraltar at Gibraltar, and the southern pillar has been identified as one of two peaks: Jebel Moussa (Musa), in Morocco, or Mount Hacho (held by Spain), near the city of Ceuta (the Spanish exclave on the Moroccan coast).”

Although these two popular sources substantially agree with each other, the concurrence is misleading. In fact, various aspects of the Pillars have been the subject of controversy for a very, very long time.

CONFUSION

The Pillars of Heracles (PoH) according to conventional wisdom were always situated somewhere in the vicinity of the Strait of Gibraltar. However, the truth is rather different. The question of the location of the Pillars has led to confusion and controversy for millennia. A flavour of this was contained in William Smith’s still highly-regarded Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography [1719] of 1854, which lists many of the locations proposed by ancient authors. One short paragraph in it encapsulates the confusion that has existed in the past and still does, although seldom highlighted, today – ” But when the ancient writers began to investigate the matter more closely, they were greatly divided in opinion as to where the Pillars were to be sought, what they were, and why they were called by the name of Hercules.”(w)

When I began my study of the Pillars, it became obvious very early on that the subject was more complicated than usually presented. Frankly, I never expected to end up as bewildered as I did. First of all, I find that some of the ancient writers have not only referred to two pillars but even three(x) and four of them.

HERAKLES

That was bad enough, but when I was then confronted with a multiplicity of mythical heroes named Herakles, numbering three (Diodorus), four (Servius), six Cicero, seven (Herodotus)(ap(z), and a prize-winning forty-four by Varro, I was even more perplexed.

Ariadna Arriaza published a paper about the multiplicity of Herakles’ in ancient texts, particularly Herodotus(z), who offered at least seven! William Smith’s Dictionary noted that “Herodotus tells us that the original Heracles hailed from Egypt and says that according to the Egyptian tradition, Heracles was one of twelve deities descended from the original eight gods who created the universe (2.43-5). Diodorus claimed that when Osiris went to accomplish his labors he left the government of Egypt in the hands of this primordial Heracles. Remarkably, Pausanias, Tacitus, and Macrobius all confirm that Heracles hailed from Egypt [1729.401]”

John K. Lundwall noted the profusion of Herakles’ [1747] and also refers to the Phoenician Herakles – Melqart and its possible influence on the development of the Greek myth. He concluded that ” Heracles was not invented by the Greeks. He was inherited by the Greeks. Half of his labors descend from Mycenaean or Minoan times, implicating a Heracles-like figure with a series of labors in the days before Greece was founded. Gilgamesh is a Near Eastern Heracles.”

Apart from the Canaanite Melqart(ak) and the biblical Samson, Herakles was also associated with Briareus or Cronos. Aelian, in his Varia Historia 5.3, noted that “Aristotle affirms that those Pillars which are now called of Hercules, were first called the Pillars of Briareus.”

Herodotus visited the temple of Heracles in Tyre with two pillars, one of gold and the other emerald. According to the priests there, it had stood for two thousand three hundred years or from approximately 2700 BC. Another suggestion has been that the ‘Pillars Heracles’ was a Greek rendering of the Egyptian ‘Pillars of Osiris’.(t)

So not only do we have a number of Heracles but also a variety of names for them.

THE NATURE OF THE PILLARS

My confusion was further compounded by the term stelai used by Plato to describe the Pillars, which is the Greek word for stone or wooden slabs used as boundary or commemorative markers, not a reference to supportive columns. I must emphasise that Plato referred to stelai, not mountains.

Rhys Carpenter favoured the idea that the term when applied to the Strait of Gibraltar was used with the sense of boundary markers, indicating ”the limits of the Inner Sea that, for the Greeks, was the navigable world” [221.156]. It is reasonable to suggest that as the Greeks became more expansionist with their trade and colonisation, new limits were set as they moved incrementally westward along with the appellation of the ‘Pillars of Hercules’.

One advocate of this idea, Thorwald C. Franke maintains that the westward shift of the ‘Pillars’ from the Strait of Messina towards Gibraltar occurred a century before Solon. He expanded on this at the 2008 Atlantis Conference [0750.170] and in his 2006 book on Herodotus [0300].

Eberhard Zangger noted [483.109] that in a 1927 article, Richard Hennig “investigated the root of the term ‘the Pillars of Heracles’ and concluded that it was not initially applied to the Straits of Gibraltar but to another locality at the end of the Greek sphere of influence.”

Further difficulties were provided by early authors describing the Pillars as mountains, statues, islands or promontories! Egerton Sykes was convinced that the Pillars had been two menhirs, 30ft tall that had stood on top of the Rock of Gibraltar(u)! In this regard, it is interesting that Jürgen Spanuth dismissed those who have identified the red and white cliffs of Heligoland as the Pillars of Heracles, decrying the idea as a fallacy [015.100]. He explained that “Natural rock formations were not what was originally meant by the Pillars of Heracles. Those at the Straits of Gibraltar were not, as one so often reads, the rocks to the north and south of the Straits, but two man-made pillars which stood before the temple of Heracles at Gades (present-day Cádiz) about 100 km north of the Straits.” Spanuth also denied that the Straits of Gibraltar were ever closed [p248].

Some of the earliest references to the Pillars of Heracles come from Pindar, who seems to have used the term as a metaphor for the limits of human capabilities, be it in sport or more usually, geographical boundaries. So as the Greeks gradually extended the range of their maritime capabilities, new boundaries were established and designated as the new Pillars of Heracles. If there had been a Metaxa Book of Records at that time it would have frequently updated the location of the ‘Pillars’.

Totally unrelated to Atlantis is the natural formation on Antigua known as the so-called Pillars of Hercules(bd).

PHOENICIAN PILLARS

Gades was originally named Gadir (walled city) and is thought to have been founded by the Phoenicians around 1100 BC and Carthage circa 814 BC, although there are question marks around both dates.(ao)

Strabo wrote; “Concerning the foundation of Gades, the Gaditanians report that a certain oracle commanded the Tyrians to found a colony by the Pillars of Hercules. Those who were sent out for the purpose of exploring, when they had arrived at the strait by Calpe, imagined that the capes which form the strait were the boundaries of the habitable earth, as well as of the expedition of Hercules, and consequently, they were what the oracle termed the Pillars. They landed on the inside of the straits, at a place where the city of the Exitani now stands. Here they offered sacrifices, which however not being favourable, they returned. After a time others were sent, who advanced about 1500 stadia beyond the strait, to an island consecrated to Hercules, and lying opposite to Onoba, a city of Iberia: considering that here were the Pillars, they sacrificed to the god, but the sacrifices being again unfavourable, they returned home. In the third voyage, they reached Gades and founded the temple in the eastern part of the island, and the city in the west. (3.5.5.) If this story has any historical basis, the first Phoenician visits to the vicinity of Gibraltar must have taken place before 1100 BC.

Heracles is the Greek counterpart of the Phoenician god Melqart, who was the principal god of the Phoenician city of Tyre. Melqart was brought to the most successful Tyrian colony, Carthage and subsequently further west, where at least three temples dedicated to Melqart have been identified in ancient Spain, Gades, Ebusus, and Carthago Nova. Across the Strait in Morocco, the ancient Phoenician city of Lixus also had a temple dedicated to Melqart.

Pairs of free-standing columns were important in Phoenician temples and are also to be found in Egyptian temples, as well as being part of Solomon’s temple (built by Phoenician craftsmen). Consequently, the pillars of Melqart temple in Gades are considered by some to be the origin of the reference to the Pillars of Melqart and later of Heracles (by the Greeks) and Hercules (by the Romans) as applied to the Strait of Gibraltar.

Greek colonisation by individual city-states got underway early in the first millennium BC. This expansion of trade and territory took place gradually during the eighth, seventh and sixth centuries BC. The online Ancient History Encyclopedia website noted that “One of the most important consequences of this process, in broad terms, was that the movement of goods, people, art, and ideas in this period spread the Greek way of life far and wide to Spain, France, Italy, the Adriatic, the Black Sea, and North Africa. In total then, the Greeks established some 500 colonies which involved up to 60,000 Greek citizen colonists, so that by 500 BCE these new territories would eventually account for 40% of all Greeks in the Hellenic World.”(aq)

While the AHE offers an excellent overview of Greek colonisation, a valuable and more detailed study is also available online(ar), namely, The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. [1752], edited by Boardman & Hammond.

LOCATION, ACCORDING TO CLASSICAL AUTHORS

Classical writers frequently refer to the ‘Pillars’ without being in any way specific regarding their location. It always seemed to me that when the Greeks began their Mediterranean trade expansion and colonisation outside the Aegean, apart from the Pentapolis of Cyrenaica in the far south and some possible trading posts in the Levant, they did so exploiting the northern shores of the Mediterranean. Understandably, they would have taken the shortest route from the Greek mainland to the heel of Italy and later on to Sicily. As this development progressed, new limits were set, and in time, exceeded. I suggest that these limits were each in turn designated the ‘Pillars of Heracles’ as they expanded further. I speculate that Capo Colonna (Cape of the Column) in Calabria(as), in South Italy, may have been one of those early boundaries. Interestingly, 18th-century maps display up to five islands near the cape, which are no longer shown on charts(at). This appeared on respected atlases as late as 1860. According to Armin Wolf, these were originally added to maps by Ortelius, inspired by some earlier cartographers and the comments of Pseudo-Skylax and Pliny(au)!

Homer did not use the term Pillars of Heracles, although he does refer to the Pillars of Atlas (Odysseus 1.51-4).

Hecataeus (550-476 BC), according to Oliver D. Smith in a 2019 paper(y), placed the PoH at Mastia, which is thought to be Cartagena in southeastern Spain. This identification is principally based on the early 20th-century studies of Adolf Schulten.

Scylax of Caryanda (late 6th & early 5th cent. BC) describes in his Periplus(a), a guide to the Mediterranean, that the Maltese Islands lay to the east of the Pillars of Heracles. This would place the archipelago east of the Gulf of Gabes, which is compatible with the opinions of Hofmann and Sarantitis. Anton Mifsud argues that had the Pillars been located at Gibraltar, the islands to the east would have been the Balearics, which was certainly true for the ancient Greek shore-hugging mariners.

Pindar (518-438 BC) would appear to have considered that the phrase ‘Pillars of Herakles’ was a metaphor for the limits of physical prowess as well-established Greek geographical knowledge (Olympian 3.43-45), a boundary that was never static for long. In 1778, Jean-Silvain Bailly was certain that the Pillars of Hercules were just “a name that denotes limits or boundaries.” [0926.2.293] More recently Professor Dag Øistein Endsjø, at the University of Oslo in Norway, has endorsed the idea that the ancient Greeks used the ‘Pillars of Heracles’ as a metaphor to express the limits of human endeavour(d) and quotes the classicist, James S. Romm in support(e). In a sentence, the Pillars advanced along with extended geographical certainty.

When the Greek expansion westward in the Mediterranean began to gather pace, no location remained long enough as the new limit of Greek influence to enable it to acquire any permanent recognition as the metaphorical Pillars of Herakles. However, when they reached the western end of the Mediterranean and were blocked by the Phoenicians, this region offered the final resting place of the ‘Pillars’, which retains the title today.

Isocrates (436-338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician and a contemporary of Plato. He wrote of Herakles setting up Pillars near Troy as a boundary marker, following the Trojan War (To Philip 5.112)(bi)(bj).

Aristotle (385-322 BC) Aristotle wrote(g) that “outside the pillars of Heracles the sea is shallow owing to the mud, but calm, for it lies in a hollow.” This is not a description of the Atlantic that we know, which is not shallow, calm or lying in a hollow and which he refers to as a ‘sea’ not an ‘ocean’.

Eratosthenes (276-194 BC) was thought by many to have been responsible for the fixing of the PoH at Gibraltar. In fact, in the early days of the compilation of Atlantipedia, I wrote that “no writer prior to Eratosthenes had referred to the Pillars of Heracles being located at Gibraltar.” This was wrong and was the result of a combination of hastily quoting Sergio Frau(al) and badly paraphrasing a passage from George Sarantitis’ book – “How, from the times of Ephorus (405 BC), Plato and Aristotle and until Eratosthenes (276 BC) and Strabo (63 BC), did the Pillars ‘migrate’ to Gibraltar?”(m)

Pseudo-Scymnus (c.140 BC) placed the Pillars at Mainake(y) thought to be modern Malaga. However, Spanuth cites from the same source a reference to a ‘Northern Pillar’ in the land of the Frisians, as support for his North Sea Atlantis!

Also in the Atlantic, there have been some speculative attempts to link the basaltic pillars at the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland and its counterpart across the sea in Scotland’s Isle of Staffa with the PoH.

Strabo (64 BC-23 AD), a Greek historian and geographer, noted that “close to the Pillars there are two isles, one of which they call Hera’s Island; moreover, there are some who call also these isles the Pillars.” (Bk.3, Chap.5) The two isles referred to as near the Pillars have never been identified; as there are no islands in or near the Strait at Gibraltar, but there are in the Sea of Marmara near the Bosporus, another location candidate!

He also records that Alexander the Great built an altar and ‘Pillars of Heracles’ at the eastern limit of his Empire.

Pliny the Elder (23/24-79 AD) noted that in Sogdiana in modern Uzbekistan there was reputed to be an altar and ‘Pillars of Heracles’.

Reginald Fessenden opted for the Caucasus noting “The fact that Nebuchadnezzar, after reaching them in his northern expedition, next went to the north shore of the Black Sea and to Thrace; and that Hercules, coming back from the pillars with the cattle of Geryon, traversed the north shore of the Black Sea (see Megasthenes, quoted by Strabo and Herodotus, 4.8), puzzled the ancient geographers because they thought that the Pillars were at the straits of Gibraltar. And because they had overlooked the fact that the Phoenicians of Sidon had known that the Pillars had been lost and that the Phoenicians had sent out four expeditions to look for them but had reached no conclusion from these expeditions except that the straits of Gibraltar were not the true Pillars of Hercules. See Strabo, 2.5.

Of course, the fact that the true Pillars of Hercules were in the north Caucasus isthmus explains why both Nebuchadnezzar and Hercules, after leaving the Pillars, came next to the shores of the Black Sea.” (w)

Tacitus (55-120 AD), the renowned Latin historian, in his Germania (chap.34), clearly states that it was believed that the Pillars of Hercules were located near the Rhine in the territory of the Frisians. So the Romans either thought that the ‘Pillars’ were not situated at Gibraltar or could exist at more than one location at the same time. In Atlantisforschung, the late Bernhard Beier, quoting Günther Nesselrath, suggests that I have overstated the value of the Tacitus reference(bg).

I contend that although there is no doubt that the term ‘Pillars of Herakles’ was eventually applied to the Gibraltar region, it was also applied to a few stops as the Greeks stuttered their way there from the Aegean along the Mediterranean. Ronald H. Fritze, an ardent Atlantis sceptic, noted in his Invented Knowledge [709.23] ” While at various times the geography of the ancient Greeks applied the name of Pillars of Hercules to other locations in the Aegean region, in this case, Plato is quite explicit that he means the Pillars of Hercules that are now known as the Straits of Gibraltar.” So if it can be accepted that the PoH was applied to several locations in the Aegean by the Greeks, why not also to other places as they gradually expanded westward?

MODERN LOCATION THEORIES

From the 19th century onwards, locations for the Pillars were proposed which stretched the length of the Mediterranean and beyond.

Perhaps the first ‘modern’ writer to propose the Eastern Mediterranean as the location for the ‘Pillars’ was a Russian, Avraam Norov (1795-1869). He considered them to have been shrines, drawing on both Greek and Arabic sources that could be investigated further.

Some also believed that other ‘Pillars of Heracles’ existed in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea region. This is possible because, until the 1st millennium BC, the Greeks were, generally speaking, restricted to those areas. It would appear that for the ancient Greeks, the Pillars of Heracles marked straits or promontories at the limits of their known world. These boundaries were gradually extended further and further as their maritime capabilities improved. and probably led to the decline in the usage of the title at former boundaries, eventually leaving us with only the Strait of Gibraltar to carry the name.

In the Late Bronze Age, the Bosporus in the east and probably the Strait of Sicily in the west confined the Greeks. It was only shortly before Solon’s trip to Egypt that the Greek colony of Massalia (modern Marseilles) was founded and so, at last, the western limit of the Mediterranean was brought within easier regular reach of Greek ships, but Massalia was still nearly 2,000 km, by sea, from Gades (Cadiz). Later their furthest trading post was probably at Mainake (Malaga), beyond which was Phoenician territory and it was 100 km from Gibraltar and 200km from Cadiz.

The idea that geographical designations can radically change their location over time is illustrated by the name (H)esperia, which means ‘evening land’ or as we might say ‘land of the setting sun’, was originally used by Greeks to indicate Italy and later employed by Roman writers as a reference to Spain. It could be argued that the Greek use of this appellation could be an indication that when introduced, they were not too sure what lay beyond Italy!

Fundamentalist Atlantology, as proclaimed by the ‘prophet’ Ignatius Donnelly in the 19th century, will accept no explanation other than that Plato was referring to ‘Pillars’ near Gibraltar‘. Certainly, it is reasonable to conclude that Plato may have been referring to the Strait of Gibraltar, but it is also evident that this was not the only location with that designation in ancient times. Consequently, if any of the alternatives mentioned above enable the construction of a new credible Atlantis location hypothesis, then it deserves careful rational consideration.

Even today, the debate continues, highlighted by modern classical scholars, such as Duane W. Roller (1946- ) in Through the Pillars of Herakles [1483.203], in which he states that “The exact location of the Pillars of Herakles was long a matter of dispute. Although they may seem obvious today as the two large mountains at the western end of the Mediterranean, Gibraltar and Jebel Mousa, such was not the case in antiquity, and understanding of the region changed as topographical knowledge increased. At some early date, Homer’s mythical and unlocated Pillars of Atlas (Od. 1.51-4) became associated with the wanderer Herakles, but as the western end of the Mediterranean became better understood in the latter seventh century BC, uncertainty increased rather than decreased. Herodotus, who mentioned the Pillars several times, placed them east of Gadeira and Tartessos (4.8, 152), which could mean anywhere in the 50-kilometer-long strait (the modern Strait of Gibraltar) that runs east to the opening of the Mediterranean, through rugged topography with several promontories that could be identified as the Pillars, although especially prominent are Gibraltar and Jebel Mousa (the Kalpe and Abilyx of Strabo) at the eastern end. The early prominence of Gadeira caused some (such as Pindar) to place them in that area, or at points east thereof, such as Tarifa or Cape Trafalgar: the sources seem uncertain as to whether height or prominence was the defining criterion.”

Several alternative locations have been identified as being referred to in ancient times as the Pillars of Heracles. Robert Schoch [0454.87] writes “This distinctive name, taken from the most powerful hero of Greek mythology, was given to a number of ancient sites known in modern times by quite different appellations. The Greeks, however, used the name Pillars of Heracles to mark other sites besides Gibraltar, some outside the Mediterranean – namely, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic and the Strait of Kerch dividing the Black Sea from the Sea of Azov – and even more inside – specifically, the Strait of Bonifacio between Corsica and Sardinia, the Strait of Messina between mainland Italy and Sicily, the Greek Peleponnese, the mountainous coast of Tunisia, and the Nile Delta.” Unfortunately, Schoch offers no references.

Even Nikolai Zhirov, a proponent of an Atlantic Atlantis, accepted that they were other locations considered to have been designated Pillars of Herakles, both within and beyond Gibraltar, as shown on a map of half a century ago in his well-regarded book [458.86]. He lists, Gibraltar, Gulf of Gabes, Kerch Strait, the Moroccan coast, the Nile Delta and the Peleponnese, but like Schoch, fails to provide references.

We also find that Arthur C. Clarke suggested that there was evidence that the early Greeks did not originally refer to the Strait of Gibraltar as the Pillars of Heracles. Clarke also failed to cite his sources but expressed a personal preference for the Strait of Messina.

WITHIN THE MEDITERRANEAN

I shall begin my review of PoH locations at the eastern end of the Mediterranean in Lebanon

TYRE

J. P. Rambling has placed the ‘Pillars’ on Insula Herculis, now a small sunken island immediately south of Phoenician Tyre(k).

BOSPORUS

Eberhard Zangger [0483] cited the work of Servius(aa) in which he wrote (“Columnas Herculis legimus et in Ponto et in Hispania”) translated by Zangger as “through the Columns of Herakles we go within the Black Sea as well as in Spain”.

A German site(ab) by Willy Dorn offers a comparable translation – “Durch die Säulen des Herakles fahren wir im Schwarzen Meer wie auch in Spanien”) “We drive through the pillars of Heracles in the Black Sea as well as in Spain”

Similarly, a Spanish author, Paulino Zamarro, wrote(ac) – (“pues sabemos de Columnas de Hércules tanto en el Ponto como en Hispania”) which translates as “for we know of Columns of Hercules both in the Ponto and hispania”.

Nicolae Densusianu offered “according to what we read, the Pillars of Hercules exist both in the Pontos region, and also in Hispania.”(ad)

The Stockton University website(ae), similarly offers “We read of pillars of Hercules both in the Black Sea and in Spain”

Whichever translation is used, it confirms that at least two locations were concurrently referred to as the ‘Pillars of Heracles’.

Werner E. Friedrich has also argued [695] in favour of Pillars at the Bosporus, citing Euctemon of Athens (c.440 BC) who described the Pillars as two islands near the entrance to the strait having characteristics comparable to Prince’s Islands in the Sea of Marmara. Friedrich quotes Ephorus identifying two islands as the Pillars, just as Strabo did (see above), although there are no islands in the Strait of Gibraltar apart from the uninhabitable islet of Perejil off the coast of Morocco. Edwin Bjorkman noted [181.62] that “the insignificant little islet of Perijil” was the chosen location of Calypso’s home by Victor Berard.

Christian & Siegfried Schoppe, in support of their Black Sea location for Atlantis, maintain that the Pillars were situated at the Bosporus and not Gibraltar. They contend “the maintained misinterpretation results from the fact that Herakles went to Iberia. At late Hellenistic and at Roman times Iberia was Spain. However, this leads to inconsistencies: After putting up the Pillars (supposed at Gibraltar) Herakles put together a fleet to go to Iberia – he was still there!” This makes no sense, however, as the Schoppes pointed out that in the distant past ‘Iberia’ related to the land of an ethnic group to the east of the Black Sea.

George K. Weller has added his support to the concept of the Pillars being situated at the Bosporus, in his brief paper on Atlantis(ba). On the other side of the Black Sea, the Strait of Kerch leading to the Sea of Azov was favoured by Alexandre Moreau de Jonnes as the site of the Pillars(bc).

TROY

Isocrates, mentioned above, recorded that following the Trojan War, Herakles set up Pillars as boundary markers near Troy – “while they with the combined strength of Hellas found it difficult to take Troy after a siege which lasted ten years, he (Heracles), on the other hand, in less than as many days, and with a small expedition, easily took the city by storm. After this, he put to death to a man all the princes of the tribes who dwelt along the shores of both continents; and these he could never have destroyed had he not first conquered their armies. When he had done these things, he set up the Pillars of Heracles, as they are called, to be a trophy of victory over the barbarians, a monument to his own valor and the perils he had surmounted, and to mark the bounds of the territory of the Hellenes.”(ax).

DANUBE

Moving eastward and inland from the Black Sea, we have a strong case presented for the Danube as the home of its own Pillars. The Danube was known to the ancient Greeks as the Istros as well as Okeanos Potamos. The lower reaches of the river have ancient and deep-rooted cultural links with Hercules that are still very obvious today.

In Romania, just north of Orsova on a tributary of the Danube lies Baile Herculane, sometimes called Hercules’ City, which has seen human habitation since the Paleolithic era. There is a legend that a weary Hercules stopped in the valley to bathe and rest. During the Roman occupation, the local Herculaneum Spa was known all over the Empire.

Pindar confirms the visit of Hercules to the Danube (Estrus)(ag).

Even as early as the 1st century BC, local coinage displayed images of Hercules(af).

Just over a century ago, Nicolae Densusianu finished his monumental work Ancient Dacia(ah), which included fifteen pages(j) of the most comprehensive and fully referenced defence of any PoH location proposed, namely, the Iron Gates gorge on the Danube in ancient Dacia – modern Romania.

Alexandra Furdui, is a Romanian architect, who now lives in Australia. In her book entitled Island: Myth…Reality …or Both? [1598], she posits Atlantis as a large island in the antediluvian freshwater Black Sea ruled by the Titans of Greek mythology, some of whom later started another civilisation in the lower Danube, where she claims the Pillars of Herakles were situated, probably the result of being influenced by the earlier work of Nicolae Densusianu.

Densusianu’s offering has been reinforced recently by Antonije Shkokljev & Slave Nikolovski–Katin who have recorded [1742] a version of the ‘Labours of Hercules’ that took place in the land of the Hyperboreans and its Danube River(ai). Other more recent writers have also specified the Iron Gates as the location of the PoH.

A paper presented at the 2008 Atlantis Conference by Ticleanu, Constantin & Nicolescu [0750.375] has the ‘Pillars’ at the Iron Gates but places Atlantis a little further west on what is now the Pannonian Plain. In 2020, Veljko Milkovi? proposed the same locations for the ‘Pillars’ and Atlantis(ay).

Similarly, an anonymous commentator, ‘Sherlock’, referencing Pindar (Olympian 3) also places the Pillars at the confluence of the Seva and Danube rivers near today’s Belgrade(s).

AEGEAN

Back in the Mediterranean, Capes Maleas and Matapan (Tainaron) in the Peloponnese are the two most southerly points of mainland Greece. They have been proposed by Galanopoulos & Bacon [0263] as the Pillars of Heracles when the early Greeks were initially confined to the Aegean Sea and the two promontories were the western limits of their maritime knowledge at that time. They argue that it is possible that the ‘Pillars of Hercules’ are not the Straits of Gibraltar.

“This has been the subject of some interesting conjectures. Nearly all the labours of Hercules were performed in the Peloponnese. The last and hardest of those which Eurytheus imposed on the hero was to descend to Hades and bring back its three-headed dog guardian, Cerberus. According to the most general version Hercules entered Hades through the abyss at Cape Taenarun (the modern Cape Matapan), the western cape of the Gulf of Laconia. The eastern cape of this gulf is Cape Maleas, a dangerous promontory, notorious for its rough seas.

Pausanias records that on either side of this windswept promontory were temples, that on the west dedicated to Poseidon, that on the east to Apollo. It is perhaps therefore not extravagant to suggest that the Pillars of Hercules referred to are the promontories of Taenarum and Maleas; and it is perhaps significant that the twin brother of Atlas was allotted the extremity of Atlantis closest to the Pillars of Hercules. The relevant passage in the Critias (114A-B) states:

‘And the name of his younger twin-brother, who had for his portion the extremity of the island near the pillars of Hercules up to the part of the country now called Gadeira after the name of that region, was Eumelus in Greek, but in the native tongue Gadeirus — which fact may have given its title to the country.’

Since the region had been named after the second son of Poseidon, whose Greek name was Eumelus, its Greek title must likewise have been Eumelus, a name which brings to mind the most westerly of the Cyclades, Melos, which is in fact not far from the notorious Cape Maleas. The name Eumelus was in use in the Cyclades; and the ancient inscription (‘Eumelus an excellent danger’) was found on a rock on the island of Thera.

In general, it can be argued from a number of points in Plato’s narrative that placing ‘the Pillars of Hercules’ at the south of the Peloponnese makes sense, while identifying them with the Straits of Gibraltar does not [p.97].”

James Mavor [265] supported Galanopoulos’ proposed location for the Pillars.

Rodney Castleden [225.6] also defended this view, noting that “before the sixth century BC several mountains on the edges of mainland Greece were seen as supports for the sky. Among others, the two southward-pointing headlands on each side of the Gulf of Laconia were Pillars of Heracles.” Other commentators have seen this identification of the Pillars as ratification of the Minoan Hypothesis(p). Caleb Howells is one of the most recent to endorse the Gulf of Laconia as the site of the Pillars(bm).

Paulino Zamarro has mapped 13 locations(f) identified as Pillars by classical authors and expands on this further in his book [0024]. He identified Pori, a rocky islet north of the Greek island of Antikythera, as the location of the Pillars.

Izabol Apulia, better known as ‘Map Mistress’ placed the Pillars on Rhodes(be).

EGYPT

In Volume No. 4 of the 1897 Science Review Journal, Alexander Karnoschitsky placed the Pillars of Heracles near Sais in Egypt and located Atlantis in the eastern Mediterranean(bb).

More recently two writers, R. McQuillen and Hossam Aboulfotouh have independently suggested the vicinity of Canopus situated in the west of the Nile Delta as the location of the ‘Pillars’. Luana Monte, a supporter of the Minoan Hypothesis has also proposed [0485] a location at the mouth of the Nile Delta where the recently rediscovered sunken city of Herakleoin was situated. This identification appears to have been made in order to keep the Minoan Empire west of the ‘Pillars’.

STRAIT of OTRANTO

Moving on, we find that Alessio Toscano has suggested that the Pillars were situated at the Strait of Otranto and that Plato’s ‘Atlantic’ was in fact the Adriatic Sea!

The Arcus-Atlantis website had the following titbit to offer(bl) – “From a very early period in their exploration of the seas around their homeland, the ancient Greeks appear to have assigned twin pillars to locations regarding as marking the furthest possible point of exploration. Perhaps the earliest of these, which are described in the De Mirabilibus Auscultatonibus, a work ascribed (wrongly) to Aristotle, were to be found in the northernmost reaches of the Adriatic Sea, either at the mouth of the River Po or just south of Istria.“

The STRAIT of MESSINA is a strong contender as a location of the PoH in the Central Mediterranean. For years I have struggled with the idea that the Atlanteans had attacked from beyond the Pillars located at Gibraltar since Plato tells us that they already had control of northern Africa and southern Italy along with several islands. To me, this could only make sense if the Pillars were situated some distance east of Gibraltar.

I recently recalled that Thorwald C. Franke had arrived at the same conclusion in a paper delivered to the 2008 Atlantis Conference held in Athens [750], where he noted that “On the one hand Atlantis is said to have ruled in Italy and Northern Africa before it invaded the region ‘within the straits’. On the other hand, Atlantis wanted to subdue ‘at a blow…..the whole region within the straits.’ How could Atlantis subdue ‘at a blow’ the ‘whole’ region ‘within the straits’ after Atlantis already had conquered the whole western Mediterranean sea”

“This is easily explained if we localise the Atlantis straits at the straits of Messina and consider the sea ‘within the straits’ to be the eastern Mediterranean sea only.”

I have discovered that in the Strait of Messina there had been a pillar erected north of the ancient city of Rhegium (Reggio Calabria), apparently marking what had been, at that time, the closest point to Sicily. Little is known about the early history of the pillar or even its precise location(av).

Some commentators had suggested the Strait of Sicily, but I find it strange that what we call today the Strait of Sicily is 90 miles wide. Now the definition of ‘strait’ is a narrow passage of water connecting two large bodies of water. How 90 miles can be described as ‘narrow’ eludes me. Is it possible that we are dealing with a case of mistaken identity and that the ‘Strait of Sicily’, when referred to in ancient times, was in fact the Strait of Messina, which is narrow? Keeping in mind that Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 AD) in his On the Eternity of the World(aj) wrote “Are you ignorant of the celebrated account which is given of that most sacred Sicilian strait, which in old times joined Sicily to the continent of Italy?” So. understandably, the Strait of Messina is a ‘prime suspect’.

On the other hand, the Strait of Messina was one of the locations known as the site of the ‘Pillars’ and considering that mariners at that time preferred to stay close to the coast, I would opt for the Strait of Messina rather than the more frequently proposed Strait of Sicily. In a 1959 article(r) entitled Atlantis – A New Theory, Arthur R. Weir investigates the story of Scylla & Charybdis and is happy to accept that it refers to features in the Strait of Messina. In commenting on the Pillars he notes it is “quite clear that while to a Roman of the time of Julius Caesar the ‘Pillars of Heracles’ meant the Straits of Gibraltar, to a Greek of six centuries or more earlier they meant the Straits of Messina, and this immediately suggests a very different location for Atlantis.” Weir goes on to suggest a location, south of Sardinia and east of the Balearics.?

SICILY

Federico Bardanzellu locates the Pillars on the island of Motya off the west coast of Sicily(h), a view that is hotly disputed. This would suggest that Atlantis was located west of there, which would bring you to Sardinia – 200 miles away. However, the Pillars were described as being close to Atlantis, which makes this suggestion improbable.

Sergio Frau in his book, Le Colonne d’Ercole: Un’inchiesta [0302], insists that the Pillars were in fact located in the Strait of Sicily. He sees this location as agreeing with the writings of Homer and Hesiod. He discusses in detail the reference by Herodotus to an island to the west of the Pillars, suggesting that the word ‘ocean’ had a different meaning than today and pointing out that elsewhere Herodotus refers to Sardinia as the largest island in the world. Following this lead, Frau concluded that Atlantis was located in Sardinia.

Louis Godart, an Italian archaeologist of Belgian extraction, has offered a number of points that support Frau’s location(bh), including one particular comment – “First of all, in the lists in our possession, there is no place name that can refer, with a minimum degree of credibility, to a toponym located west of the Strait of Sicily.” I think that this should be investigated further as Godart offers no references and the implications, if verified, are far-reaching.

SARDINIA

Sardinia has considerable support as the location of Atlantis. This idea appears to have had addition support from Professor Giorgio Saba who has identified Carloforte on the island of San Pietro off the southwest coast of Sardinia as the site of the Pillars of Heracles, known locally as the ‘Faraglione Antiche Columns’.

Sardinia has considerable support as the location of Atlantis. This idea appears to have had addition support from Professor Giorgio Saba who has identified Carloforte on the island of San Pietro off the southwest coast of Sardinia as the site of the Pillars of Heracles, known locally as the ‘Faraglione Antiche Columns’.

STRAIT of BONIFACIO

The Strait of Bonifacio is the name of the 11km stretch of water that lies between Sardinia and Corsica. As mentioned above, Robert Schoch included this strait in a list of locations that he believes were formerly designated by the Greeks as ‘Pillars of Heracles’, alas, all without references. Paolo Valente Poddighe who nominated Sardinia and Corsica as Atlantis 40 years ago, also situated the ‘Pillars’ at Bonifacio.

MALTA

As Felice Vinci mentioned earlier, according to Aristotle, the Pillars of Heracles were also known by the earlier name of ‘Pillars of Briareus’ (Aelian Var. Hist.5.3). Plutarch places Briareus near Ogygia, from which we can assume that the Pillars of Heracles are close to Ogygia [019.270]. Since Malta is identified by some as Ogygia, it is not unreasonable, to conclude that the Pillars were probably in the region of the Maltese Islands.

Anton Mifsud has now revised his opinion regarding the Pillars and in a December 2017 illustrated article(o) he identified the Maltese promontory of Ras ir-Raheb near Rabat, with its two enormous limestone columns as the Pillars of Herakles. This headland had originally been topped by a Temple of Herakles, confirmed by archaeologist, Professor Nicholas Vella. A 2020 article about the Minoans offered additional support for this location(v).

STRAIT OF SICILY

Robert J. Tuttle is the author of The Fourth Source [1148], in which he touched on the subject of Atlantis, takes issue with the translations of Plato’s text by Bury and Lee, who refer to the ‘Atlantic Ocean’, which he claims should read as the ‘Sea of Atlantis’ and locates the ‘Pillars of Herakles’ somewhere between Tunisia, Sicily and the ‘toe of Italy’.

Pier Paolo Saba also placed the PoH between Sicily and Tunisia.

Rosario Vieni has suggested that the Symplegades, at the Bosporus, encountered by Homer’s Argonauts were precursors of the Pillars of Heracles, although Vieni settled on the Strait of Sicily as their location [1177] before Sergio Frau adopted the same location. However, there is little doubt that during the last two centuries, BC ‘the Pillars’ referred almost exclusively to the Strait of Gibraltar.

Delisle de Sales placed the ‘Pillars’ not too far away at the Gulf of Tunis, the gateway to Carthage.

GULF OF GABES

As mentioned above Scylax of Caryanda described in his Periplus(a) that the Maltese Islands lay to the east of the Pillars of Heracles, which would place the archipelago east of the Gulf of Gabes. Antonio Usai, in a critique of Frau’s book Usai, opted for the Pillars having been between the east coast of Tunisia and the islands of Kerkennah in the Gulf of Gabes [0980]. George Sarantitis presented a paper to the 2008 Atlantis Conference in which he also argued that the Pillars had been situated in the Gulf of Gabes [750.403]. He cites Strabo among others to highlight the multiplicity of locations that have been attributed to Pillars in ancient times.

Ulrich Hofmann combines the Periplus of Scylax with the writings of Herodotus to build a credible argument for placing Atlantis in North Africa in Lake Tritonis, now occupied by the chotts of modern Algeria and Tunisia. Consequently, Hofmann places the Pillars in the Gulf of Gabés. Hofmann also argues that the Pillars were part of Atlantis rather than separate from it.

I must not forget Paul Borchardt who advocated Tunisia as the location of Atlantis. In a map drawn by him (see left), he placed the Pillars (Columnae Herculis) at the Gulf of Gabes(bf).

I must not forget Paul Borchardt who advocated Tunisia as the location of Atlantis. In a map drawn by him (see left), he placed the Pillars (Columnae Herculis) at the Gulf of Gabes(bf).

Alan Mattingly strongly supports the Gulf of Gabes as at least one location for the ‘Pillars’. I have taken the liberty of quoting his comments in full from his very interesting Kindle book Plato’s Atlantis and the Sea Peoples: A Review of Context and Evidence [1948].

“Further, Herodotus strongly implies that the Pillars of Herakles that he is talking about are located near to Gabes in the Little Syrtis. ‘I have now mentioned all the pastoral tribes along the Libyan coast. Up country further to the south lies the region where wild beasts are found, and beyond that there is a great belt of sand stretching from Thebes in Egypt to the Pillars of Herakles. (Book IV.181) Thus far I am able to give you the names of the tribes who inhabit the sand belt, but beyond this point my knowledge fails. I can affirm, however; that the belt continues to the Pillars of Herakles’ and beyond…’ (Book IV.185) Since Herodotus’ tribal descriptions do not go west of Carthage these statements suggest that the Pillars of Herakles he is referring to lie somewhere within the Gulf of Sirte. I would note that there is a sand belt that indeed extends from Egypt through Libya to southern Tunisia and Algeria, although not in one unbroken mass. It does not however go further west than the ouadi Rhir, there are separate sand seas to the south-west in Mauretania and Mali, but it should be noted that there is no great sand belt in the vicinity or anywhere near the Straits of Gibraltar. Since Herodotus is professing no knowledge of what lies beyond the Atlantes or beyond Carthage along the North African Coast the implication would be that the Pillars are to the East of these points (along the coast south and east of Carthage). Since the sand belt touches the coast last near Gabes, the further implication is that the Pillars were in this vicinity.”

GIBRALTAR

There is no doubt that the region of Gibraltar was considered, at least by the Greeks, to be home to the Pillars from the middle of the first millennium BC. However, although sought by Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans, they were never found. I am forced to contend that they were principally metaphorical.

Oliver D. Smith investigated the matter of the ‘Pillars’ and concluded that there were four locations in southern Iberia nominated as home to the Pillars and named them as Mastia, Mainake, Strait of Gibraltar and Cádiz(az).

In 1916, Konrad Miller, the German historian, who published a number of old maps offered one that purported to show the ‘Pillars’ just west of Gibraltar. What is unusual about this is that it is depicted on an island!(m)

There is one interesting comment by the late Steven Sora [395.6] that may have a bearing on the location of the Pillars of Heracles, where, citing Ernle Bradford [1011], he claimed that at the time when Homer wrote, around 775 BC, the Greeks had barely ventured as far as Italy. To me, this would appear to suggest that at that time it is improbable that the ‘Pillars’ were identified by the Greeks with Gibraltar, but more likely to have been somewhere in the Central Mediterranean. Nevertheless, Sora opted for the Gibraltar location [p217]!

BEYOND GIBRALTAR

A more distant location was proposed by Chechelnitsky who placed the ‘Pillars’ at the Bering Strait between the Chukchi and Seward peninsulas in Russia and the USA respectively.

Arguably the most unusual suggestion this year has come from Marco Goti in his book, The Island of Plato [1430] in which he identified the ‘Pillars’ in the Atlantic, being the basalt columns of the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland in the west and their counterpart in Scotland’s Isle of Staffa in the east! However, this idea is not original, having been first mooted nearly seventy years ago by W.C. Beaumont(n). Alberto Majrani is a recent advocate of this interpretation(bk).

The Cyclopean Islands off the east coast of Sicily near Mt. Etna and referred to by Homer in his Odyssey are also known for their basaltic columns.

Olof Rudbeck‘s chosen location was further east in the Baltic at the Øresund Strait between Sweden and Denmark.

Ogygia has also been identified with one of the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic by Felice Vinci [019.3], who then proposed that the Pillars of Heracles had also been located in that archipelago. John Larsen has made similar suggestions.

Exotic locations such as Chott-el-Jerid in Tunisia, Bab-el-Mandeb(b) at the mouth of the Red Sea, the Strait of Hormuz(i) at the entrance to the Persian Gulf and even the Palk Strait between Sri Lanka and India have all been suggested at some stage as the ‘Pillars’.

George H. Cooper offered [0236] an even more outrageous solution when he wrote that the megaliths of Stonehenge in England were the original Pillars of Heracles.

In 2018, David L. Hildebrandt published Atlantis–The Awakening [1602], in which he endeavoured to do just that with a mass of material that he claims supports the idea of Atlantis in Britain and Stonehenge as the remnants of the Temple of Poseidon. He suggests that the five trilithons represent the five sets of male twins, an idea voiced by Jürgen Spanuth and more recently by Dieter Braasch.

The late Arysio dos Santos [0320] claimed that “there was only one real pair of pillars: the ones that flank Sunda Strait in Indonesia”, in keeping with his Indonesian location for Atlantis. However, he does offer a map showing [p.130] nine sites designated by ancient authorities (but without references) as having been locations of ‘Pillars’, reinforcing the idea that the term was not exclusively applied to just one site. Santos’ map was based on the work of José Imbelloni.

ATLANTIS AND THE PILLARS OF HERACLES

The assumed location of the Pillars of Heracles, at the time of Solon, often plays a critical part in the formulation of the many Atlantis theories on offer today. Even the authors of theories that have placed Plato’s island civilisation in such diverse locations as Antarctica, the North Sea or the South China Sea, have felt obliged to include an explanation for the nature and location of the ’Pillars’ within the framework of their particular hypothesis.

There is one location clue in Plato’s text (Tim.24e) that is often overlooked, namely, that the island of Atlantis was situated close to the Pillars of Heracles. Although it can be argued that Plato’s island was immediately before or beyond the Pillars, the text seems to clearly imply proximity. This was pointed out by W.K.C. Guthrie in volume V of A History of Greek Philosophy [0946.245] and independently endorsed by Joseph Warren Wells in The Book on Atlantis [0783].

Sometimes, in ancient Greek literature, this phrase PoH refers to the strait between Sicily and the southern tip of Italy (a place which the Greeks did know well, having established colonies in Sicily and Southern Italy). An indication of the level of confusion that existed in early geography and cartography is the fact that some ancient maps & texts mark the Mediterranean region west of the Strait of Sicily as ‘the Atlantic Ocean‘ and even state that Tyrrhenia is in the ‘Atlantic’!

Finally, my own conclusion regarding the location of the ‘Pillars’ is that a careful reading of Plato’s text shows clearly that they were located in the Central Region of the Mediterranean. I base this view on Critias 108 which states that the Atlantean war was between those that lived outside the Pillars of Heracles and those that lived within them and (ii) Critias 114 which declares that Atlantis held sway over the Western Mediterranean as far as Tyrrhenia in the north and up to the borders of Egypt in the south. Consequently, we can safely assume that the west of Tyrrhenia and Egypt was beyond the Pillars of Heracles. Depending on the exact location of the ancient borders of Tyrrhenia and Egypt, the Pillars were probably situated somewhere in the vicinity of the Strait of Sicily.

This interpretation opens up the possibility of Malta, Sicily or even Sardinia as prime candidates for the location of Atlantis, with the ‘Pillars’ probably being at the Strait of Messina between Sicily and mainland Italy. My principal reason is that a strait is defined as “a naturally formed, narrow, typically navigable waterway that connects two larger bodies of water.” The Strait of Sicily is 145 km wide and cannot be realistically considered a strait. Similarly, it can be argued that at 13 km in width, the Strait of Gibraltar cannot be described as ‘narrow’! On the other hand, the Strait of Messina, which at its narrowest is 3.1 km wide, fits the bill perfectly. Andis Kaulins is similarly inclined to favour the Central Mediterranean, also with the Strait of Messina as his prime candidate(q).

What is clear from all of the above is that the term Pillars of Heracles was, without doubt, applied to a variety of locations but Plato’s reference might relate to Gibraltar although equally strong if not stronger cases can be made for other sites at earlier dates. It is also plausible that at some point it also became a metaphor for any geographical limit.

CONCLUSION

Leaving aside the multiplicity of Herakles’ noted above, it is clear that the Herakles associated with Pillars was a mythological figure and when taken together with the fact that the ancient writers could not agree on the exact location or the nature of the Pillars and combined with the failure of both the Phoenicians and later the Romans to find them, it is reasonable to conclude that there were no physical Pillars of Herakles at Gibraltar.

It should be obvious that if the ancient mariners, Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans, despite centuries of searching, were unable to definitively identify the location of the Pillars, making my suggestion, that they were not physical but metaphorical, more credible.

Furthermore, the Gibraltar region together with all the other locations proposed for the Pillars of Herakles, none are known to have possessed the stelai described by Plato.

The PoH are described by Plato in terms implying proximity to Atlantis. He also described Atlantis as being beyond the Pillars of Herakles or westward of them. Furthermore, without any ambiguity, Plato identified central Mediterranean territory in southern Italy and northern Africa together with a number of the many islands there, as the Atlantean domain. Consequently, we must look to somewhere not too far east of those lands for the location of the Pillars. My personal choice is the Strait of Messina, one of the proposed locations named the Pillars on their journey westward in step with the expansion of Greek trade and colonisation.

As explained elsewhere, ancient empires or alliances only expanded by invading contiguous territory or attacking by sea, land that is within ‘easy reach’. From Gibraltar to Athens is over 2,500 km, which would make an attack over that distance totally irrational, whereas an invasion launched from southern Italy across the Strait of Otranto to mainland Greece is quite credible.

However, my view now is that generally, most references to Pillars of Herakles noted above used the term metaphorically to indicate an unspecified geographical limitation.

TRIVIA

Apart from any connection with Atlantis, it has been suggested that the vertical lines in the US dollar $ign (and by extension on the Bitcoin logo) represent the Pillars of Heracles!(l)

A more ‘out of this world’ suggestion(c) is that the ‘Pillars’ were actually two bright stars in the western sky at the end of the last Age of Libra around 12,500 BC.

(a) http://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/archaeology/people/shipley/pseudo-skylax

(b) http://www.grahamhancock.com/underworld/DrSunilAtlantis.php

(c) http://dailygrail.com/blogs/Charles-Pope/2011/8/Atlantis-Above-and-Below-Part-3

(d) https://web.archive.org/web/20020603011136/http://www.gunnzone.org:80/constructs/endsjo.htm

(f) La localización de la Atlántida (archive.org)

(g) .ii.html”http://classics.mit.edu?Aristotle/meteorology.2.ii.html

(h) https://web.archive.org/web/20200403114225/http://www.museodeidolmen.it/popomare.html

(i) https://web.archive.org/web/20200220020342/http://www.middle-east.mavericsa.co.za/history.html (over halfway down the page)

(j) https://shebtiw.wordpress.com/the-sea/the-pillars-of-hercules/

(k) http://redefiningatlantis.blogspot.ie/search/label/Heracles

(l) http://www.pravda-tv.com/2016/07/atlantis-die-dollar-note-und-die-saeulen-des-herakles/

(m) http://gibraltar-intro.blogspot.ie/2015/10/bc-pillars-of-hercules-if-ordinary.html

(n) https://www.theflatearthsociety.org/library/pamphlets/Is%20Britain%20the%20Lost%20Atlantis.pdf

(p) https://stillcurrent.wordpress.com/2016/04/05/atlantis-maybe-not-so-lost/

(q) https://web.archive.org/web/20200130221548/http://www.lexiline.com/lexiline/lexi60.htm

(r) https://drive.google.com/file/d/10JTH401O_ew1fs8uhXR9C5IjNDvqnmft/view Science Fantasy #35 1969

(s) https://sherlockfindsatlantis.wordpress.com/

(t) (Atlantean) Research, Vol 1 No.2, July/August , 1948

(u) Atlantis, Vol.29, No.2, March 76.

(v) https://www.argophilia.com/news/was-the-end-of-the-minoans-the-will-of-the-gods/227053/ (near the end of page)

(w) http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0064:entry=herculis-columnae-geo

(x) http://dlib.nyu.edu/awdl/isaw/isaw-papers/5/

(y) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334683935_In_Search_of_the_Pillars_of_Heracles

(z) (Microsoft Word – Numéro complet.docx) (univ-lille.fr)

(aa) Servius on Vergil’s Aeneid 11.262.1

(ab) Atlantis – a lost paradise? – On the coasts of light (archive.org) (German)

(ac) La localización de la Atlántida (archive.org)

(ae) https://www.stockton.edu/hellenic-studies/documents/chs-summaries/culley94.pdf

(af) http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/celtic/danube/i.html

(ag) Pindar, Olympian 3.25

(ai) https://www.academia.edu/30587794/_Cradle_of_the_Aegean_Culture_by_Antonije_Shkokljev_and_Slave_Nikolovski_Katin?email_work_card=view-paper (Chap. 16)

(aj) https://web.archive.org/web/20200726123301/http:/www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book35.html, v139

(ak) https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Anabasis_of_Alexander/Book_II/Chapter_XVI

(al) https://www.chasingtheunexpected.com/sardinia-land-of-mystery-part-2-atlantis-lost-civilization/

(am) Plato’s Atlantis (Decoding the most famous myth) English translation of ‘The Apocalypse of a Myth’, 2017

(an) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claudius_Aelianus#Varia_Historia

(ao) https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/199203/pillars.of.hercules.sea.of.darkness.htm

(ap) II, 42.44 {4747}

(aq) https://www.ancient.eu/Greek_Colonization/

(as) https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/capo-colonna

(at) https://nl.pinterest.com/pin/734438651719489108/

(au) See: Note 5 Armin Wolf’s Wayback Machine (archive.org)

(av) https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonna_Reggina

(aw) http://www.radiocom.net/Deluge/Deluge7-10.htm

(ax) Isocrates. To Philip 5.112

(ay) Pannonian Atlantis by Veljko Milkovi? | VEMIRC

(az) https://www.academia.edu/39947152/In_Search_of_the_Pillars_of_Heracles

(bb) Alexander Nikolajewitsch Karnoschitsky – Atlantisforschung.de

(bc) Alexandre Moreau de Jonnès – Atlantisforschung.de

(bd) https://www.islandroutes.com/caribbean-tours/antigua/9284/pillars-of-hercules-hiking-adventure

(be) http://pseudoastro.wordpress.com/2009/02/01/planet-x-and-2012-the-pole-shift-geographic-spin-axis-explained-and-debunked/ (Comment March 9, 2009, about halfway down the page)

(bf) Paul Borchardt: Atlantis in Tunisia – Atlantisforschung.de (atlantisforschung-de.translate.goog)

(bh) The Archaeologist / Louis Go

(bi) https://greekreporter.com/2023/05/25/pillars-hercules-greek-mythology/

(bk) https://ilionboken.w ordpress.com/insight-articles/guest-article-where-were-the-pillars-of-hercules/

(bl) Where exactly is Atlantis? (archive.org) (p.3)

(bm) What Are the Pillars of Hercules Mentioned in Greek Mythology? – GreekReporter.com

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

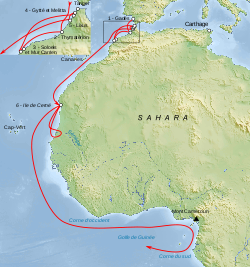

Hanno, The Voyage of *

The Voyage of Hanno, the Carthaginian navigator, was undertaken around 500 BC. The general consensus is that his journey took him through the Strait of Gibraltar and along part of the west coast of Africa. A record, or periplus, of the voyage was inscribed on tablets and displayed in the Temple of Baal at Carthage. Richard Hennig  speculated that the contents of the periplus were copied by the Greek historian, Polybius, after the Romans captured Carthage. It did not surface again until the 10th century when a copy, in Greek, was discovered (Codex Heildelbergensis 398) and was not widely published until the 16th century.

speculated that the contents of the periplus were copied by the Greek historian, Polybius, after the Romans captured Carthage. It did not surface again until the 10th century when a copy, in Greek, was discovered (Codex Heildelbergensis 398) and was not widely published until the 16th century.

The 1797 English translation of the periplus by Thomas Falconer along with the original Greek text can be downloaded or read online(h).

Edmund Marsden Goldsmid (1849-?) published a translation of A Treatise On Foreign Languages and Unknown Islands[1348] by Peter Albinus. In footnotes on page 39 he describes Hanno’s periplus as ‘apocryphal’. A number of other commentators(c)(d) have also cast doubts on the authenticity of the Hanno text.

Three years after Ignatius Donnelly published Atlantis, Lord Arundell of Wardour published The Secret of Plato’s Atlantis[0648] intended as a rebuttal of Donnelly’s groundbreaking book. The ‘secret’ referred to in the title is that Plato’s Atlantis story is based on the account we have of the Voyage of Hanno.

Nicolai Zhirov speculated that Hanno may have witnessed ‘the destruction of the southern remnants of Atlantis’, based on some of his descriptions.

Rhys Carpenter dedicated nearly twenty pages to the matter of Hanno commented that ”The modern literature about his (Hanno’s) voyage is unexpectedly large. But it is so filled with disagreement that to summarize it with any thoroughness would be to annul its effectiveness, as the variant opinions would cancel each other out”[221.86]. Carpenter included what he describes as ‘a retranslation of a translation’ of the text.

Further discussion of the text and topography encountered by Hanno can be read in a paper[1483] by Duane W. Roller.

What I find interesting is that so much attention was given to Hanno’s voyage as if it was unique and not what you would expect if Atlantic travel was as commonplace at that time, as many ‘alternative’ history writers claim.

However, even more questionable, is the description of Hanno sailing off “with a fleet of sixty fifty-oared ships, and a large number of men and women to the number of thirty thousand, and with wheat and other provisions.” The problem with this is that the 50-oared ships would have been penteconters, which had limited room for much more than the oarsmen. If we include the crew, an additional 450 persons per ship would have been impossible, in fact, it is unlikely that even the provisions for 500 hundred people could have been accommodated!

Lionel Casson, the author of The Ancient Mariners[1193] commented that “if the whole expedition had been put aboard sixty penteconters, the ships would have quietly settled on the harbour bottom instead of leaving Carthage: a penteconter barely had room to carry a few days’ provisions for its crew, to say nothing of a load of passengers with all the equipment they needed to start a life in a colony.“

The American writer, William H. Russeth, commented(f) on the various interpretations of Hanno’s route, noting that “It is hard for modern scholars to figure out exactly where Hanno travelled, because descriptions changed with each version of the original document and place names change as different cultures exert their influence over the various regions. Even Pliny the Elder, the famous Roman Historian, complained of writers committing errors and adding their own descriptions concerning Hanno’s journey, a bit ironic considering that Romans levelled the temple of Ba’al losing the famous plaque forever.”

George Sarantitis has a more radical interpretation of the Voyage of Hanno, proposing that instead of taking a route along the North African coast and then out into the Atlantic, he proposes that Hanno travelled inland along waterways that no longer exist(e). A 2013 report in New Scientist magazine(n) revealed that 100,000 years ago the Sahara had been home to three large rivers that flowed northward, which probably provided migration routes for our ancestors. Furthermore, if these rivers lasted into the African Humid Period they may be interpreted as support for Sarantitis’ contention regarding Hanno!

He insists that the location of the Pillars of Heracles, as referred to in the narrative, matches the Gulf of Gabes [1470].

The most recent commentary on Hanno’s voyage is on offer by Antonio Usai in his 2014 book, The Pillars of Hercules in Aristotle’s Ecumene[980]. He also has a controversial view of Hanno’s account, claiming that in the “second part, Hanno makes up everything because he does not want to continue that voyage.” (p.24) However, the main objective of Usai’s essays is to demonstrate that the Pillars of Hercules were originally situated in the Central Mediterranean between eastern Tunisia and its Kerkennah Islands.

A 1912 English translation of the text can be read online(a), as well as a modern English translation by Jason Colavito(k).

Another Carthaginian voyager, Himilco, is also thought to have travelled northward in the Atlantic and possibly reached Ireland, referred to as ‘isola sacra’. Unfortunately, his account is no longer available(g).

The controversial epigrapher Barry Fell went so far as to propose that Hanno visited America, citing the Bourne Stone as evidence!(m)*

The livius.org website offers three articles(i) on the text, history and credibility of the surviving periplus together with a commentary.

Another excellent overview of the document is available on the World History Encyclopedia website.(l)

(a) https://web.archive.org/web/20040615213109/https://www.jate.u-szeged.hu/~gnovak/f99htHanno.htm

(c) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanno_the_Navigator

(d) https://annoyzview.wordpress.com/2012/04/

(e) https://platoproject.gr/voyage-hanno-Carthaginian/

(f) https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/1033187.William_H_Russeth/blog?page=2 *

(g) https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2011/12/13/high-north-carthaginian-exploration-of-ireland/

(j) BSMQgoYSQYFJ90bRJIhQ&hl=mt&ei=–tuSfNEIaqnAOo_NjHBA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=&ved=CBgQ https://archive.org/details/cu31924031441847

(l) Hanno: Carthaginian Explorer – World History Encyclopedia

(n) NewScientist.com, 16 September 2013, https://tinyurl.com/mg9vcoz

Tartessos

Tartessos or Tartessus is generally accepted to have existed along the valley of the Guadalquivir River where the rich deposits of copper and silver led to the development of a powerful native civilisation, which traded with the Phoenicians, who had colonies along the south coast of Spain(k).

A continuing debate is whether Tartessos was developed by a pre-Phoenician indigenous society or was a joint venture by locals along with the Phoenicians.(o) One of the few modern English-language books about Tartessos was written by Sebastian Celestino & Carolina López-Ruiz and entitled Tartessos and the Phoenicians in Iberia [1900].

A 2022 BBC article offers some additional up-to-date developments in the studies of Tartessos(v).

It is assumed by most commentators that Tartessos was identical to the wealthy city of Tarshish that is mentioned in the Bible. There have been persistent attempts over the past century to link Tartessos with Atlantis. The last king of Tartessia, in what is now Southern Spain, is noted by Herodotus to have been Arganthonios, who is claimed to have ruled from 630 BC until 550 BC. Similarly, Ephorus a 4th century BC historian describes Tartessos as ‘a very prosperous market.’ However, if these dates are only approximately true, then Atlantis cannot be identified with Tartessos as they nearly coincide with the lifetime of Solon, who received the story of Atlantis as being very ancient.

However, the suggested linkage of Tartessos with Atlantis is disputed by some Spanish researchers, such as Mario Mas Fenollar [1802] and Ester Rodríguez González(n). Mas Fennolar has claimed that at least a thousand years separated the two. Arysio dos Santos frequently claimed that Atlantis was Tartessos throughout his Atlantis and the Pillars of Hercules [1378].

The existence of a ‘Tartessian’ empire is receiving gradual acceptance. Strabo writes of their system of canals running from the Guadalquivir River and a culture that had written records dating back 6,000 years. Their alphabet was slightly different to the ‘Iberian’. The Carthaginians were said to have been captured by Tartessos after the reign of Arganthonios and after that, contact with Tartessos seems to have ended abruptly!

The exact location of this city is not known apart from being near the mouth of the Guadalquivir River in Andalusia. The Guadalquivir was known as Baetis by the Romans and Tartessos to the Greeks. The present-day Gulf of Cadiz was known as Tartessius Sinus (Gulf of Tartessus) in Roman times. Cadiz is accepted to be a corruption of Gades that in turn is believed to have been named after Gaderius. This idea was proposed as early as 1634 by Rodrigo Caro (image left), the Spanish historian and poet, in his Antigüedades y principado de la Ilustrísima ciudad de Sevilla, now available as a free ebook(i).

In 1849, the German researcher Gustav Moritz Redslob (1804-1882) carried out a study of everything available relating to Tartessos and concluded that the lost city had been the town of Tortosa on the River Ebro situated near Tarragona in Catalonia. The idea seems to have received little support until recently, when Carles Camp published a paper supporting this contention(w). It was written in Valenciano, which is related to Catalan and can be translated with Google Translate using the latter option.

A few years ago, Richard Cassaro endeavoured to link the megalithic walls of old Tarragona with the mythical one-eyed Cyclops and for good measure suggest a link with Atlantis(l). Concerning the giants, the images of doorways posted by Cassaro are too low to comfortably accommodate giants! Cassaro has previously made the same claim about megalithic structures in Italy(m)

The German archaeologist Adolf Schulten spent many years searching unsuccessfully for Tartessos, in the region of the Guadalquivir. He believed that Tartessos had been founded by Lydians in 1150 BC, which became the centre of an ancient culture that was Atlantis or at least one of its colonies. Schulten also noted that Tartessos disappeared from historical records around 500 BC, which is after Solon’s visit to Egypt and so could not have been Atlantis.

Richard Hennig in the 1920s also supported the idea of Tartessos being Atlantis and situated in southern Spain. However, according to Atlantisforschung he later changed his opinion opting to adopt Spanuth’s Helgoland location instead(x).

Otto Jessen, a German geographer, also believed that there had been a connection between Atlantis and Tartessos. Jean Gattefosse was convinced that the Pillars of Heracles were at Tartessos, which he identifies as modern Seville. However, Mrs E. M. Whishaw, who studied in the area for 25 years at the beginning of the 20th century, believed that Tartessos was just a colony of Atlantis. The discovery of a ‘sun temple’ 8 meters under the streets of Seville led Mrs Whishaw to surmise[053] that Tartessos may be buried under that city. Edwin Björkman wrote a short book, The Search for Atlantis[181] in which he identified Atlantis with Tartessos and also Homer’s Scheria.

book, The Search for Atlantis[181] in which he identified Atlantis with Tartessos and also Homer’s Scheria.

Steven A. Arts, the author of Mystery Airships in the Sky, also penned an article for Atlantis Rising in which he suggests that the Tarshish of the Old Testament is a reference to Tartessos and by extension to Atlantis(r)!

More recently Karl Jürgen Hepke has written at length, on his website(a), about Tartessos. Dr Rainer W. Kühne, following the work of another German, Werner Wickboldt, had an article[429] published in Antiquity that highlighted satellite images of the Guadalquivir valley that he has identified as a possible location for Atlantis. Kühne published an article(b) outlining his reasons for identifying Tartessos as the model for Plato’s Atlantis.

Although there is a consensus that Tartessos was located in Iberia, there have been some refinements of the idea. One of these is the opinion of Peter Daughtrey, expressed in his book, Atlantis and the Silver City[0893] in which he proposes that Tartessos was a state which extended from Gibraltar around the coast to include what is today Cadiz and on into Portugal’s Algarve having Silves as its ancient capital.

It was reported(c) in January 2010 that researchers were investigating the site in the Doñana National Park, at the mouth of the Guadalquivir, identified by Dr Rainer Kühne as Atlantis in a 2011 paper(s). In the same year, Professor Richard Freund of the University of Hartford garnered a lot of publicity when he visited the site and expressed the view that it was the location of Tartessos which he equates with Atlantis. The Jerusalem Post in seeking to give more balance to the discussion quoted archaeology professor Aren Maeir who commented that “Richard Freund is known as someone who makes ‘sensational’ finds. I would say that I am exceptionally skeptical about the thing, but I wouldn’t discount it 100% until I see the details, which haven’t been published as far as I know.”(u)

A minority view is that Tarshish is related to Tarxien (Tarshin) in Malta, which, however, is located some miles inland with no connection to the sea. Another unusual theory is offered by Luana Monte, who has opted for Thera as Tartessos. She bases this view on a rather convoluted etymology(e) which morphed its original name of Therasia into Therasios, which in Semitic languages having no vowels would read as ‘t.r.s.s’ and can be equated with Tarshish in the Bible, which in turn is generally accepted to refer to Tartessos.

Giorgio Valdés favours a Sardinian location for Tartessos(f), an idea endorsed later by Giuseppe Mura in his 2018 book, published in Italian, Tartesso in Sardegna [2068], the full title of which translates as Tartessos in Sardinia: Reasons, circumstances and methods used by ancient historians and geographers to remove Tartessos (the Tarshish of the Bible) from Caralis and place it in Spanish Andalusia. Caralis is an old name for Cagliari, the Sardinian capital.

Andis Kaulins has claimed that further south, in the same region, Carthage was possibly built on the remains of Tartessos, near the Pillars of Heracles(j).

A more radical idea was put forward in 2012 by the Spanish researcher, José Angel Hernández, who proposed(g)(h) that the Tarshish of the Bible was to be found in the coastal region of the Indus Valley, but that Tartessos was a colony of the Indus city of Lhotal and had been situated on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar!

A recent novel by C.E. Albertson[130] uses the idea of an Atlantean Tartessos as a backdrop to the plot.

A relatively recent claim associating Tartessos with Atlantis came from Simcha Jacobovici in a promotional interview(p) for the 2017 National Geographic documentary, Atlantis Rising. In it, Jacobovici was joined by James Cameron as producer, but unfortunately, the documentary did not produce anything of any real substance despite a lot of pre-broadcast hype.

There is an extensive website(d) dealing with all aspects of Tartessos, including the full text of Schulten’s book on the city. Although this site is in Spanish, it is worthwhile using your Google translator to read an English version.

“Today, researchers consider Tartessos to be the Western Mediterranean’s first historical civilization. Now, at an excavation in Extremadura—a region of Spain that borders Portugal, just north of Seville—a new understanding of how that civilization may have ended is emerging from the orange and yellow soil. But the site, Casas del Turuñuelo, is also uncovering new questions.”(q) First surveyed in 2014 it was in late 2021, a report emerged of exciting excavations there that may have a bearing on the demise of Tartessos. Work is currently on hold because of a dispute with landowners, with only a quarter of the site uncovered. The project director is Sebastian Celestino Perez. The Atlas Obscura website offers further background and details of discoveries at the site(t).

(a) http://web.archive.org/web/20170716221143/http://www.tolos.de/History%20E.htm

(b) Meine Homepage (archive.org)

(d) TARTESSOS.INFO: LA IBERIA BEREBER (archive.org)

(e) http://xmx.forumcommunity.net/?t=948627&st=105

(f) http://gianfrancopintore.blogspot.ie/2010/09/atlantide-e-tartesso-tra-mito-e-realta.html

(g) http://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/mito-y-religion/

(h) http://joseangelh.wordpress.com/category/arqueologia-e-historia/

(j) Pillars of Heracles – Alternative Location (archive.org)

(k) Archive 3283 | (atlantipedia.ie)

(n) (PDF) Tarteso vs la Atlántida: un debate que trasciende al mito (researchgate.net)

(o) (PDF) Definiendo Tarteso: indígenas y fenicios (researchgate.net)